Background

Nicole Stormon

Global Oral Health and Workforce Needs

The global burden of oral diseases remains a significant public health challenge, with conditions such as dental caries, periodontal diseases, and oral cancers affecting billions of people worldwide (Jin et al. 2016). These diseases not only cause pain and discomfort, but also leads to substantial economic and social burdens due to lost productivity and increased healthcare costs (Jin et al. 2016). Over the past century, many countries introduced dental auxiliaries to supplement the dentist workforce to extend the reach of dental care. These practitioners operate under various titles such as dental hygienists, dental therapists, and oral health therapists. They play a critical role in providing preventive and restorative services. The scope of practice for these professionals varies across different regions, reflecting local needs, regulatory environments, and educational frameworks.

The school dental nurse program was established in New Zealand in 1921 (Leslie 1971). This initiative was developed to address the high prevalence of dental caries among school-aged children, particularly in rural and underserved areas. School dental nurses were trained to provide preventive and basic restorative dental care within the school setting, significantly improving access to dental services for children. This program proved highly successful and became a model for similar initiatives worldwide, demonstrating the effectiveness of utilising trained dental professionals to enhance public oral health outcomes.

History in Australia

The concept of an auxiliary dental profession was introduced to Australia in 1965, inspired by the successful New Zealand school dental nurse model. The National Health and Medical Research Council reported a shortage in the dentist workforce and at its 60th session recommended training female dental nurses (Image 1).

“The National Health and Medical Research Council, at its 60th Session in October, 1965, recommended that, to relieve the shortage of dentists in Australia, Commonwealth and State clinics and school dental services should consider the employment of adequately trained female dental nurses as auxiliary personnel, to undertake limited procedures under the supervision of qualified dentists. It was also in October, 1965 that the Australian Dental Association adopted a policy supporting the employment of school dental nurses in Australia. At present the Australian Capital Territory and three States, New South Wales, Tasmania and South Australia, are moving forward quickly with plans to expand their school dental by utilising these auxiliary personnel. It Is anticipated that in the A.C.T. the first will be employed in 1967.”

Source: The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. Annual Report by the Director-General of Health for Year 1965-66. Parliamentary Paper No. 170. Commonwealth Government Printing Office Canberra: 1966. Page 36.

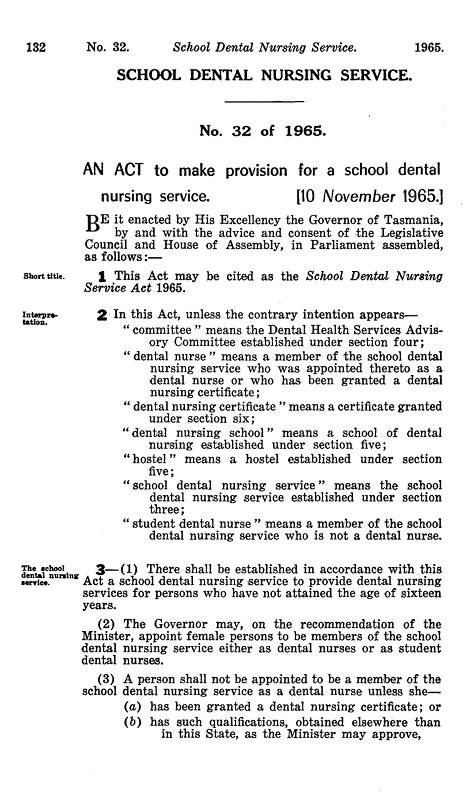

The School Dental Nursing Service Act 1965 of Tasmania was established (Image 2) on the 10th of November 1965. This Act in Tasmania was superseded in 1976 with the School Dental Therapist Service Act 1976. These Acts, as well as other State and Territory Acts subsequently implemented, defined the qualification, entry requirements and role of the school dental therapist. The first dental therapy training program had its first intake of students in Tasmania in 1966, and South Australia shortly after in 1967.

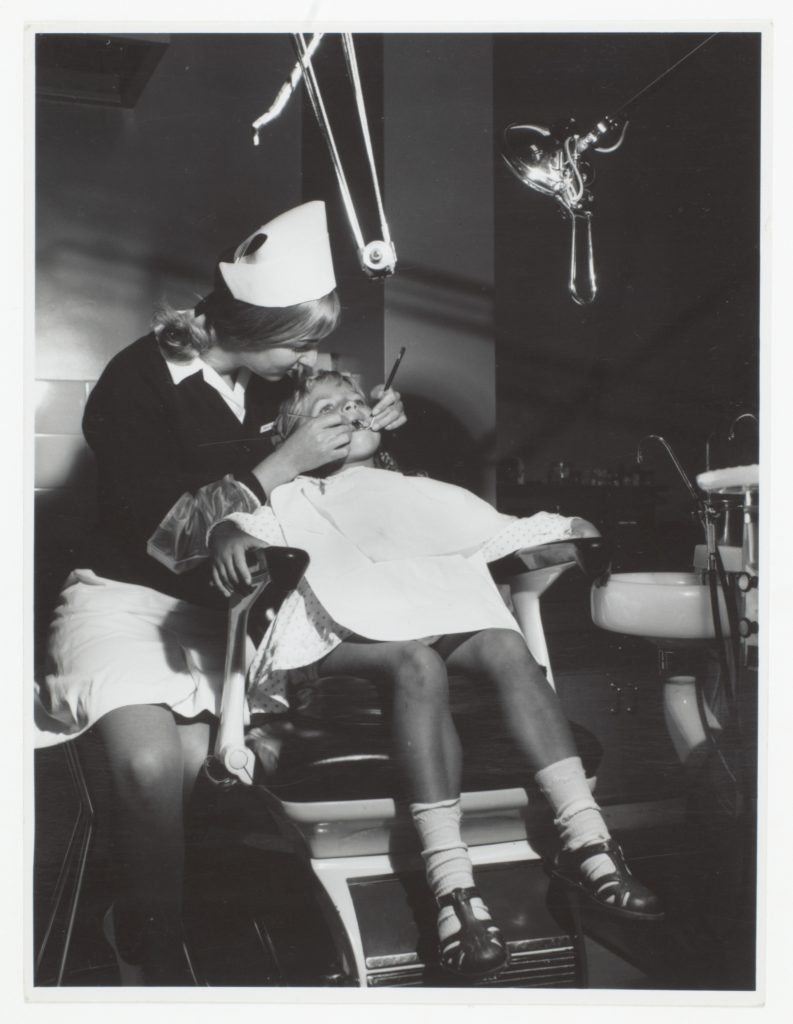

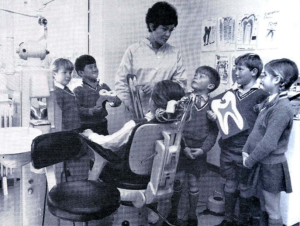

Dental therapy curricula were originally two-years in length and trained practitioners to perform restorations and extractions on children under the supervision of dentists. Trainee Dental therapists were required to be female and unmarried (Image 3). Before the expansion of dental therapy programs into other states, areas like the Australian Capital Territory sent students to train in the Tasmanian program. Blaike (1974) published an overview of the curriculum for dental therapy training in South Australia (Blaikie 1974).

“Details regarding the training and employment of dental therapists were finalised during the year. These dental auxiliaries will, under the supervision of dentists, carry out the simpler types of fillings and extractions for children. To qualify as a dental therapist, suitable applicants of matriculation standard will be trained in Hobart for a two-year period. The first four students began their training in January 1968. The training school in Hobart is under the control of the Tasmanian Department of Health Services, with whom agreement was reached regarding the training of Commonwealth students.”

Source: The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. Annual Report by the Director-General of Health for Year 1967-68. Parliamentary Paper No. 181. Commonwealth Government Printing Office Canberra: 1968. Page 46-47.

Image 2. The Tasmanian School Dental Nursing Service Act 1965.

Image 3. Trainee dental therapist in the Tasmanian program.

“Training facilities for ten Commonwealth dental therapists-in-training were provided in Hobart by the extension of the Tasmanian Training School. This building extension, together with the necessary equipment, was financed by the Commonwealth. Up to five Commonwealth dental therapists will graduate each year from the School. The first four therapists will complete their training in December, 1969.”

Source: The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. Annual Report by the Director-General of Health for Year 1968-69. Parliamentary Paper No. 170. Commonwealth Government Printing Office Canberra: 1969. Page 44.

“The recruitment of dentists has continued to be a problem, although the position has been relieved by the employment of four dental therapists who completed their training in December, 1969. These are the first dental therapists to be employed in the Dental Service in the A.C.T.”

Source: The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. Director-General of Health. Annual Report for Year 1969-70. Parliamentary Paper No. 185. Commonwealth Government Printing Office Canberra: 1970. Page 52.

The NHMRC reported in the Director-General of Health Annual publication the progress of the implementation of the first dental therapy programs between the years of 1966 and 1970. Upon completion of their training, Dental therapists were employed within the school dental service to meet the unmet oral health needs of children. The Tasmanian Government in 1967 published a video of the training and work of a dental therapist, which is openly available through the Libraries Tasmania.

The profession of Dental hygiene was introduced to Australia in the late 1970s. The first Dental hygiene training program was established at the Adelaide Dental Hospital in South Australia in 1977. Similar, to Dental therapy the dental hygiene profession worked under the supervision of a Dentist performing periodontal skills. Early Dental hygiene training in Australia was one year in length teaching students about diseases aetiology, prevention and scaling techniques for the management of periodontal diseases (McIntyre 1982).

Over time, the role of a Dental hygienist and Dental therapist in Australia expanded to include a broader population and scope of skills. In 1991, The University of Queensland introduced a Bachelor of Applied Sciences in Oral Health. This tertiary level program brought together the training of Dental hygiene and Dental therapy for dual qualification of both professions (Tsang 2010). Following The University of Queensland, the next university to offer a dual qualification program was the Bachelor of Oral Health (BOH) at the University of Adelaide in 2002 (Rogers et al. 2018).

The title “Oral health therapist” was officially introduced in Australia following changes to the Dental Board of Australia’s Scope of Practice in 2006. This change integrated the roles of Dental hygienist’s and Dental therapist’s into a single, dual-qualified profession known as Oral health therapy. This restructuring aimed to streamline education and training pathways while expanding the scope of practice to include a broader range of preventive and restorative dental services. Consequently, individuals graduating from accredited programs were awarded the title of Oral health therapist, reflecting their dual qualifications and enhanced role within the dental profession in Australia.

The shift towards integrated oral health therapy programs meant that new graduates from around the mid-2000s onwards were trained as dual-qualified Oral health therapists rather than solely as Dental therapists. Due to the implementation of Oral health therapy program, all Dental therapy programs were superceeded and there currently are no programs graduating dental therapists in Australia.

Current Australian Context

The introduction of national registration under the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra) in July 2010 marked a major milestone for oral health professionals. Since its establishment, AHPRA has overseen the national registration and accreditation of health practitioners, including those in the oral health field. This unified system ensures consistent standards of practice and professional accountability across the country, providing a cohesive regulatory framework for dental practitioners.

In this report the umbrella term Oral Health Practitioner (OHP) is used to refer to the collective of the Ahpra registered practitioners including Dental hygienist (DH), Dental therapist (DT), Oral health therapist (OHT) or combination of these. In 2020, (OHPs) were included in the Health Professionals Award. This milestone provided a formal structure for employment conditions, including wages, work hours, and other employment rights, thereby improving job security and professional recognition for these practitioners.

Historically, the Dental Board of Australia required OHPs to work within a structured professional relationship with a dentist. This requirement was part of the scope of practice standard and guidelines, which limited the independence of Dental hygienists, Dental therapists, and Oral health therapists. In 2020, the Dental Board of Australia revised its scope of practice standard, resulting in a landmark development for the profession. The key changes included the removal of the structured professional relationship requirement, granting OHPs professional autonomy. The term “not an independent practitioner” was eliminated from the standard. This recognised that all dental practitioners, including Dentists, Dental prosthetists, DHs, DTs, and OHTs, are responsible for their professional decisions, treatments, and the advice they provide.

Following the recognition of OHPs as independent practitioners, significant progress was made towards securing Medicare provider numbers for these professionals. Obtaining Medicare provider numbers was a crucial advancement allowing OHPs to participate in Commonwealth-funded schemes. The increase in professional autonomy and recognition of the OHP role allows for less reliance on Dentists and thereby expanding access to dental care for the Australian public.

In 2023, approximately 5000 individuals were registered as an OHP (Dental Board of Australia, 2023). There are currently two accredited training programs for dental hygiene, one delivered by Technical and Further Education (TAFE) and another by a university (Dental Board of Australia, 2024). Additionally, there are eight Bachelor of Oral Health (BOH) programs graduating Oral health therapists (Dental Board of Australia, 2024).

Purpose and Scope of the Study

The Australian Oral Health Workforce Study aims to understand and describe the oral health professions working conditions across the country. Building upon the first study published in 2020, this follow-up report seeks to describe the workforce post-COVID pandemic and commence a longitudinal cohort study to investigate insights into the dynamics of the workforce over time (Stormon et al. 2020). The primary objectives of this study are to assess workforce demographics, geographic distribution, and practice patterns. Continued investigation into the OHP workforce enables policymakers and stakeholders to make informed decisions regarding workforce planning and resource allocation. Understanding workforce characteristics and distribution ensures OHPs meet the evolving needs of the Australian population.

Sources

- Blaikie, D.C. (1974), Dental Therapists in South Australia. Australian Dental Journal, 19: 384-388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.1974.tb02368.x

- Dental Board of Australia, Registrant Data, AHPRA, Editor. 2023.

- Dental Board of Australia. Approved programs of study. 2024. [Accessed 18/06/2024]; Available from: https://www.dentalboard.gov.au/Accreditation/Programs-of-study.aspx.

- Jin LJ, Lamster IB, Greenspan JS, Pitts NB, Scully C, Warnakulasuriya S. Global burden of oral diseases: emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral diseases. 2016 Oct;22(7):609-19.

- Leslie, G.H. (1971), More about dental auxiliaries. Australian Dental Journal, 16: 201-209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.1971.tb03408.x

- McIntyre, J.M. (1982), The establishment of a course to train dental hygienists in South Australia: an evaluation after three years. Australian Dental Journal, 27: 189-194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.1982.tb04084.x

- The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. Annual Report by the Director-General of Health for Year 1965-66. Parliamentary Paper No. 170. Commonwealth Government Printing Office Canberra: 1966. Page 36.

- The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. Annual Report by the Director-General of Health for Year 1967-68. Parliamentary Paper No. 181. Commonwealth Government Printing Office Canberra: 1968. Page 46-47.

- The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. Annual Report by the Director-General of Health for Year 1968-69. Parliamentary Paper No. 170. Commonwealth Government Printing Office Canberra: 1969. Page 44.

- The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. Director-General of Health. Annual Report for Year 1969-70. Parliamentary Paper No. 185. Commonwealth Government Printing Office Canberra: 1970. Page 52-53.

- Rogers J, Townsend G, Brown T. The Adelaide Dental School 1917 to 2017. Barr Smith Press: Adelaide. 2018.

- Stormon N, Tran C, Suen B. Australian oral health workforce: the oral health professions workforce survey 2020.

- Tasmanian Government. Tasmanian Legislation. School Dental Nursing Service Act 1965. Tasmania’s consolidated legislation online. Accessed 17/06/2024. https://www.legislation.tas.gov.au/view/html/inforce/2000-07-01/act-1965-032/lh

- Tsang, A. K. L. (2010). Oral health therapy programs in Australia and New Zealand: emergence and development. Knowledge Books and Software.

Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency

Oral health practitioner

Dental Hygienists

Dental Therapists

Oral Health Therapists

Technical and Further Education

Bachelor of Oral Health