The lifecycle of a financial instrument in flow-of-funds diagrams

$diagram will need to be improved$

The essential function of a financial system is to channel money from people and organisations with an excess of funds towards people and organisations with funding needs. Financial instruments – like shares, bonds, loans, term deposits, saving accounts, commercial paper or commercial bills – are the contracts that are provided in exchange for money, allowing funding to take place in the financial system.

The daily operation of the economy crucially relies on the funding function of the financial system. Households usually do not have enough savings to buy a house or a car and therefore need loans. Similarly, most businesses need external funding to build a new plant or to buy machinery; for that purpose, they issue bonds or shares or take a loan to raise the money they need. Governments as well do not always collect enough taxes to pay their staff or build roads and, as a result, need to get a loan or issue bonds. They may well receive enough taxes to finance their expenses overall but still need to borrow money at short term from others to meet their expenses, such as paying staff wages, when the taxes have not yet been collected. In all these stories, financial instruments (like loans, shares or bonds) are necessarily provided in exchange for money .

The recipient of funds creates and gives, or ‘issues’, a financial instrument to the provider of funds. Financial instruments are like receipts; they are evidence that some money has changed hands. They are also legal documents that describe the payments that the recipient of funds commits to make in the future to the holder of the financial instrument. The investor in the financial instrument, i.e. the entity that owns it, is entitled to future payments from the issuer of the financial instrument, i.e. the entity that created that instrument to raise funds in the first place.

What we do in this chapter

In this chapter, we explain in detail the very basics of a financial instrument. Many misconceptions in finance and economics can be traced back to these foundations not being fully understood. Studying the basics of a financial instrument is therefore essential to be able to comprehend more complex topics and to avoid confusion.

We explain how financial instruments relate to the channelling of money, so that the fundamental function of the financial system can be understood. We describe the nature of the funds that are transferred, i.e. bank deposits. We identify the two parties involved in the financial contract: on one side, the provider of funds (who in return is the investor in the financial instrument) and on the other side, the recipient of funds (who is the issuer of the financial instrument). We use flow-of-funds diagrams to represent graphically the transfers of funds. We represent the flow of money at each stage of a financial instrument’s lifecycle, i.e. at its creation, at the time when payments of interest or dividends take place, at the time when it is transferred to another investor and finally at its destruction, when the funds are eventually paid back.

*****In the next chapter, we will retell the same story but this time through balance sheets; we will describe how the balance sheets of the parties involved in the financial instrument are affected. We will show how each stage in the life of the financial instrument affects the assets, liabilities and equity of the provider and recipient of funds. We therefore tell the life story of the financial instrument through basic accounting. This accounting approach will complete the picture started by the flow-of-funds diagrams and brings the understanding of financial instruments to a more analytical level.*****

The general principles are initially explained for a generic financial instrument (i.e. without specifying one product in particular), as the focus is on the common characteristics and roles of financial instruments in the economy. Three realistic stories referring to real financial instruments are later used throughout the remainder of the chapter to illustrate the fundamental concepts and to highlight the differences among financial instruments. The first example tells the story of the Australian Commonwealth government issuing bonds that are initially bought by the superannuation fund UniSuper and later resold to AustralianSuper. The second story is about the mining company Rio Tinto issuing shares that become part of UniSuper’s portfolio and later of the managed fund Perpetual’s portfolio. Finally, the third illustration shows the finance company GE Money making a loan to the Smith’s household. These examples give us the opportunity to present the features of three very common financial instruments – bonds, shares and loans – and the role of three important financial institutions – superannuation companies, managed funds and finance companies.

In this chapter (and in next chapter as well), we deliberately do not include commercial banks in our analysis despite bank loans and bank saving accounts representing large volumes in the financial system. The reason for excluding them in this chapter is because commercial banks play a unique role as managers and creators of money (bank deposits) in the economy; this essential function drastically affects the way banks record transactions in their balance sheets and the way money flows when banks are the issuers of the financial instrument or the investors in the financial instrument. Because the mechanisms are fundamentally different when banks are involved in a financial instrument, they need to be analysed in a separate chapter. For the time being, commercial banks are only considered in their capacity as managers of bank deposits, the money that in our context is exchanged for a financial instrument or used for paying the contractual income associated with that financial instrument.

Through the representation of the lifecycle of a financial instrument in the flow-of-fund diagram and in balance sheets, we will have the opportunity to explain the difference between selling a financial instrument and issuing a financial instrument, which is very commonly mixed up. The distinction between the contractual flow of income and the capital gain/loss of a financial security, which are both part of the yield of a security, will be clarified. We will also describe two distinct components of equity for a company: the accumulated profits and the shares on issue. We will show that funding is a distinct concept from payment. We will cover the more technical accounting aspect of how capital gains are recorded, through amortization, in the balance sheets of issuers and investors.

Structure of the chapter

The chapter is composed of the following sections:

- Channelling funds: the role of financial instruments

- The lifecycle of a financial instrument in a flow-of-funds diagram

- Flows of funds diagram for a bond, a share and a non-bank loan

- Conclusion

Sections 1 and 2 explain the core principles for a generic product. Section 3 illustrates the same concepts for real specific financial instruments. If the reader needs a break, the best moment would be after Section 2.

1 The role of financial instruments in the channelling of funds

The main function of the financial system is to make money/funds flow from agents with available funds to agents in need of funds. This section shows how the initial stage in the life of a financial instrument – its creation and transfer to a first investor – fills the role of channelling funds in the financial system.

1.1 What funds are

In our field of study, funds and money are synonyms, and their main purpose is to be used for payment. The first representation that comes to mind when we think of money is cash, i.e. the physical notes and coins that can be put in a wallet or in the pocket. Despite its visibility, tangible cash is only a very small component of money. Notes and coins are rapidly declining in popularity as a means of payment, even for basic daily expenses like grocery shopping or drinks at the local coffee shop.

In a modern economy, money predominantly takes the form of bank deposits, a balance in an account at a commercial bank [1]. This type of money is intangible in the sense that it has no physical existence: you cannot hold it in your hand or put it in your wallet. Bank deposits are purely book keeping entries, numbers in a book. Nowadays, with the development of information technologies, deposit money is electronic and takes the form of a number in a database, rather than in a book.

The term ‘deposits’ is somewhat unfortunate as the existence of bank deposits is not conditional on people actually depositing notes and coins in a bank. The idea of bank deposits being cash deposited in a bank is a well spread misconception that we wish to correct at once, as it is the source of serious misunderstandings on how banks operate. At the origin of the confusion is the reality that one increases the balance in a bank deposit account by bringing some cash at the branch counter and, conversely, one decreases the balance by withdrawing cash at the ATM for example. Nevertheless, most deposits in a bank are not the result of cash deposits. Because bank deposits are book keeping entries, they can be created without cash being handed in. In a later chapter we will study how new deposits appear, for instance, through the process of a loan made by a bank. For the moment, the reader only needs to know that bank deposits are an alternative form of money to cash, that they can easily be converted into cash and that they are the most frequently used form of money in a modern economy. In the financial system the funds used in exchange for financial instruments and for the payment of interest and dividends are exclusively banks deposits, never cash.

Given the intangible nature of deposits, a transfer of funds in the financial system does not require physical transportation but simply takes the form of a balance increase in the deposit account of the recipient of funds and a balance decrease in the deposit account of the provider of funds, both of these changes being initiated by an electronic signal.

Not all bank deposit accounts can be used for payment. The funds that circulate as payment in the economy, and in the financial system in particular, are exclusively balances in bank transaction accounts (also called in the literature current accounts or demand deposits). This type of account takes various nicknames from bank to bank, for marketing purposes, such as Australia Smart Access or Complete access accounts (CBA), Classic banking account (NAB), Access Advantage (ANZ) or Choice account (Westpac ). They usually come with cheque books, debit cards and direct transfers to activate the funds for payment.

Term deposits (where the funds are locked in for a certain period and gain interest) and saving accounts (which have no term but still earn interest) cannot be used for transactions: these deposits need to be transferred first into transaction accounts in order to be used for payments. [2] In Australia, some banks and shopkeepers unfortunately use the term ‘saving’ when referring to a transaction account, thereby creating confusion in the mind of the public. [3]

What we call funds in the context of the financial system are therefore exclusively transaction deposits in banks. We will refer to transaction deposits as ‘bank deposits’ for short, keeping in mind that this definition rules out term deposits and proper saving accounts. [4]The approach taken in this book is that transaction deposits are money/funds as they can be used for payment whereas term deposits and saving accounts are financial instruments as they cannot be used for payment.

1.2 Who need funds from an external source ? Who have funds available for others?

A household that wants to consume more than its income (and does not wish to sell its belongings) needs to find the funds from another source. A business that wants to buy a machine or a building and does not have enough profit to finance it needs to receive the funds externally. A government that spends more than it gets from taxes and other income needs to find the funding for the deficit from another source. Finally, any financial company (ignoring banks) with a plan to lend money or invest money in the financial system needs to collect funds first. All of these persons and organisations that need funds from a third party become ‘recipients of funds’, once a financial contract is arranged.

Be aware that an entity that wants to consume more than its income but is willing to sell some of its belongings to get funds does not need to find funds from an outside source.

A household that earns more than its consumption and its real investment[5] has funds available for others. A business that has some profit left after paying its shareholders and doing real investment has some funds available to invest in the financial markets. A government with more income than its spending can make the budget surplus available to others. A financial company (ignoring banks) which has collected funds will have them available to outsiders. All of these persons and organisations that have an excess of funds can become ‘providers of funds’ in a financial contract.

Be aware that an entity that has some income left after consumption and real investment may decide to pay back existing debts instead of making the funds available to the financial system.

1.3 How financial instruments channel funds

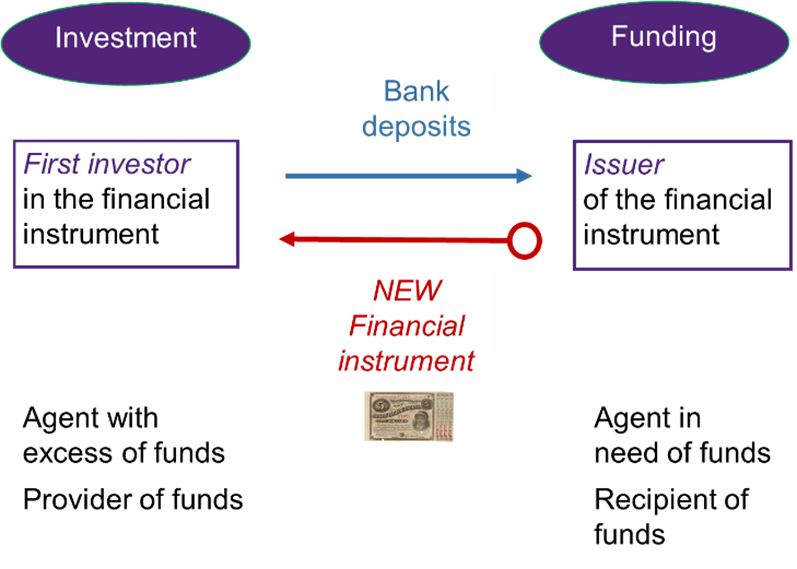

When a financial instrument is created, funds flow towards the agent (household, government or business) in need of money in exchange for the financial instrument going in the opposite direction. The entity in need of money creates/issues a NEW financial instrument to give to the entity that provides funds. These opposite movements of funds and financial instrument are represented below in a flow-of-funds diagram.

Throughout the book, funds (bank deposits) are represented in blue while the financial instrument appears in red (and italics for those who do not have the luxury of a colour printer). Because the financial instrument is issued at this stage, the arrow starts with a circle that symbolises creation. That convention will be useful to flag a financial transaction that involves a new instrument as opposed to an existing instrument. The financial instrument here is symbolised by a paper form; nevertheless, in a modern financial system, a financial instrument is not tangible and only exists digitally in a database. In our example, the owner of the financial instrument is the investor, the agent who provided funds, with the expectation to get a future flow of income from the financial instrument. Note that the issuer that received funds is not the original owner of the financial instrument as it created it so that the investor, the first owner of the instrument, can get it.

The issuance of a financial instrument is the only stage in the lifecycle of the product that actually ‘provides funds’, i.e. transfers money from the investor to the issuer. All subsequent transfers of funds, related to that financial contract, do not constitute channelling of funds from agents in surplus to agents in deficit of funds.

2. The lifecycle of a financial instrument in flow-of-funds diagrams

2.1 Creation of a financial instrument

The ‘birth’ of a financial instrument, when it appears for the first time in the financial system, is the stage of the lifecycle described in section A. This is the unique moment in the life of the financial instrument when it brings funds to its creator. This step in the lifecycle provides funding.

Issuer and first investor

For all financial instruments except loans, the product is created and designed by the entity that requires funds. The entity that creates the financial instrument [and designs it to its needs] in order to receive funds is the issuer of the financial instrument. The issuer’s name appears on the document, confirming that this entity has received funds in the first place and will have to make future payments to whoever holds the financial instrument. Usually the issuer creates many identical financial instruments at the same time, which will facilitate later trade. Between the moment the issuer designs the financial instrument, usually with the help of an investment bank, and the moment the issuer finds an entity to take it, the financial instrument does not officially exist and does not appear anywhere in the books of the issuer. It is therefore wrong to think that the issuer is the owner of any unsold financial instrument it has created.

A loan creation is slightly different from the process described above in the sense that the loan contract is designed by the provider of funds not the recipient of funds. The entity in needs of funds approaches the lender (bank or finance company) to apply for a loan and then the lender designs a unique financial contract (the loan) specifically tailored for that customer. Although the recipient of funds initiated the process when applying for a loan, the design of the financial instrument is ultimately made by the provider of funds. As a result, we usually avoid the term ‘issuer’ for the recipient of funds in the case of a loan; we simply call the recipient of funds in a loan contract the ‘borrower’.

In all cases – loans or other financial instruments – the entity that gave the funds and now owns/holds the financial instrument is called the investor in the financial instrument.

Terms of the financial contract

The financial instrument specifies the terms of the deal:

- the maturity date (if any)

- the type and frequency of payments to the holder of the financial instrument during the life of the product

- the amount of repayments

- the seniority, i.e. priority ranking of repayments with respect to other creditors that the recipient of funds may have to pay back as well.

Primary market

Because a new product is created, the market in which the financial instrument is issued is commonly referred to as a primary market. Usually for securities, which are standardised products, the issue consists of a very large number of perfectly identical instruments. For a loan, which is not a standardised product but tailored to a specific customer, the financial instrument is unique. For that reason, we avoid speaking of ‘market’ for loans. Nevertheless, the notion of ‘primary’ for the creation of the loan contract is still relevant.

2.2 Contractual payments during the life of the financial instrument

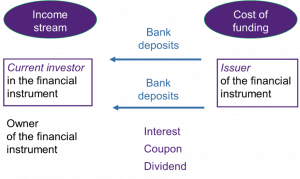

Providers of funds in the financial system are not altruistic: they agree to supply funds only because they expect more funds in return. During the lifecycle of the financial instrument, some funds therefore have to move in the opposite direction, this time from the issuer of the financial product to the investor. These funds paid in addition to the original amount represent the remuneration paid by the issuer to the investor – interest (debt) or dividends (share) – to compensate the investor for sacrificing consumption and real investment through the provision of funds to others.

There is no exchange of financial instrument at this stage of the lifecycle; it is exclusively funds that change hands. These additional funds represent the contractual income (for the investor) and the contractual expense (for the issuer) associated with the existing financial instrument. We will explain later why this part of the story now affects the parties’ profit/saving/surplus[6] whereas the channelling of funds permitted by the financial instrument at its creation is not part of the profit or equivalent.

The frequency and the value of the payments during the life of the instrument are specified in the financial contract. They can differ widely from one instrument to another. For very short-term instruments, there are usually no payments until the maturity date. Sometimes, usually for long-term loans, the funds paid are not only the remuneration on the loan (the interest) but also the gradual repayment of the original amount lent (the principal).

Note that the payments by the issuer of the financial instrument are made to the current investor, who may well not be the initial provider of funds. The reason is that the original provider of funds may have sold the financial instrument to another investor. The issuer of the financial instrument is always in charge of making payments (since he/she[7] is the one who received the funds in the first place!) while the contractual payments will go to anyone holding the financial instrument at the time these payments are due. Issuers know who to pay, as the ownership is recorded in a registry and updated when the financial instrument is sold.

2.3 Transfer of the financial instrument among investors

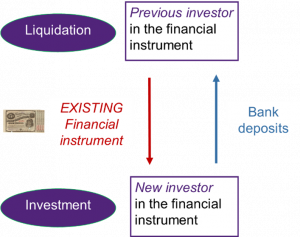

Once issued, most financial instruments can change hands among investors. By buying the financial instrument from the previous investor, a new investor provides funds to the previous investor. This step in the lifecycle of the financial instrument is liquidation.

We deliberately represent this transaction in a vertical way as it involves an existing financial instrument issued in the past and takes place among investors, keeping the issuer of the financial instrument out of the deal. In Section A, the transaction was drawn horizontally as it was between the issuer and the first investor.

Contrary to Section A, there is no circle at the start of the red arrow because the financial instrument is not being created; it already exists. The previous investor gets funds through the sale but not by issuing a new financial instrument. The previous investor liquidates an existing financial asset, i.e. substitutes money for the financial instrument she had in her portfolio.

Secondary market

Because the trade involves exclusively existing products, i.e. financial instruments issued in the past, the market in which this trade takes place is called a secondary market.

The role of the secondary market is to allow investors to get rid of their investment before the maturity date, without recalling the funds from the issuer. The issuer can keep the funds provided for as long as scheduled in the contract. Another investor simply takes over the contract and becomes the official counterparty in that contract. From the point of view of the issuer, the future payments now go to the new investor ‘as if’ the new investor had provided the funds to the issuer in the first place (even though it is not the case). The exchange of a given financial instrument among investors in the secondary market may happen several times. Consequently, the identity of the owner of the financial instrument can change several times. Through one single financial instrument, an issuer may actually be funded by a sequence of different investors.

The financial instrument transferred to another investor has kept all its original features.

The amount of funds paid by the new investor to the previous investor is the price of that instrument as determined by demand and supply in the secondary market at the time of the exchange.[8]

A few financial instruments cannot be transferred to another investor. The only option then is to bring back the financial instrument to its issuer. That is the case for term deposits and saving accounts in the bank and for units issued by managed funds. This implies that the issuer is uncertain for how long she can keep the funds that were provided and this can put her in difficulty if she does not have the money to pay back the instrument when requested.

Capital gain/loss

As the price in the secondary market fluctuates, it is very likely that the previous investor sold the instrument at a different price than the one at which she bought it in the past. The difference between the selling price and the buying price represents an income for the seller. It could be a negative income if the price has decreased during the time she held the financial instrument in her portfolio. Note that even though the selling price determines the inflow of money it is not the income. Only the difference between the selling price and the buying price is an income. This form of income is not a contractual income: it cannot be specified in the terms of the contract as it depends on the market price variation, which is unknown at the time of the design of the contract.

A loan can also be sold to another investor (another lender). However, there is no market for trading existing loans as each loan contract is unique. The selling price is then a private negotiation between the current lender and the possible buyer, rather than the result of the demand and supply in a market with many identical securities. Selling a loan is therefore more difficult than selling a security and that is the reason why securitisation, which we cover in a different chapter, is useful to the lender who no longer wishes to have some loans in its portfolio.

2.4 Destruction through redemption of the financial instrument or buyback

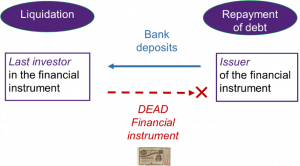

If the financial instrument has a maturity date, the income payments described earlier made by the issuer to the investors cease at that date.

The last payment scheduled in the financial contract is made by the issuer to the current (and last) investor and this last payment cancels/destroys the contract. Think of it as the last investor returning the financial instrument to the issuer and being paid for it. The flow is exactly the opposite of what happened at the time of the creation of the financial instrument, although it may not be with the same investor.

Returning the financial instrument to its issuer does not mean that the issuer owns it from now on but simply that the financial instrument disappears from the financial system, as symbolized by the cross.

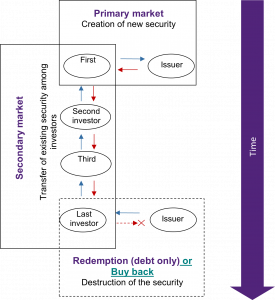

2.5 Summary of the lifecycle of a financial instrument: distinction primary market and secondary market

Securities are first created in the primary market. It is the only time in the life of the product that funds are actually brought to the issuer of the financial instrument.

Once issued, financial instruments can change hands many times among investors. In the secondary market, funds are brought to investors who want to get rid of the financial instrument by new investors happy to be involved in the financial contract with the issuer.

Financial instruments trade in the secondary market up to their maturity date, at which time the issuer redeems the security at its face value. After this point the financial instrument no longer exists.

The lifecycle of the financial instrument is represented in the flow-of-funds diagram below. Following our previous convention, the red arrow symbolises the movement of the financial product while the blue one is associated with the funds.

Figure 5 Flow-of-funds diagram of the overall lifecycle of a security

Figure 5 Flow-of-funds diagram of the overall lifecycle of a security

- Some non-bank institutions, like building societies or credit unions in Australia, also offer deposit accounts. For simplicity, we will only refer to banks in this chapter. ↵

- Term deposits and saving accounts are included in some official monetary aggregates like M2 or M3, and, as such, are considered as money in some statistics. However, they cannot directly be used in the payment system. ↵

- When an Australian shopkeeper asks `cheque or saving?` as a customer hands over a debit card, she actually refers to two types of transaction deposit accounts, rather than saving accounts defined here. ↵

- In accounting, the term ‘cash’ has a different meaning, as it comprises any form of money: notes, coins and bank deposits. ↵

- The difference between consumption and real investment is that a consumption good disappears whereas an investment good does not. For instance food belongs to consumption whereas houses are real investment. The word ‘real’ refers to the spending on goods to distinguish from ‘financial’ investment, which consists of owning financial instruments. ↵

- We will see later in the chapter that the terminology ‘profit’ applies for a commercial company, ‘saving’ for a household and ‘surplus’ for a government. The three terms represent the same concept: the difference between income and expense. ↵

- For simplicity, in the rest of the text I will simply use ‘she’ instead of ‘he/she’. ↵

- When the organisation of the market is through dealers, several prices may coexist for the same instrument. For this kind of market, there will be also a distinction between buying price and selling price. We will study this market structure in a later chapter. ↵