Securitisation, as the name suggests, leads to the creation of new ‘securities’ using as a foundation assets that are NOT securities. More precisely, securitisation is the process of creating/issuing new securities, bonds, notes or commercial paper, whose income will come directly from the income generated by a specified pool of existing assets, most likely loans, which are NOT securities.

As securitisation involves both a security as a new instrument and a non security as the source of income, it is worthwhile to revisit the concept of security. In Chapter 1, we define security as being a financial instrument that is tradable in a secondary market. Instruments such as bonds, notes and commercial paper (but also shares, capital notes, and commercial bills) have in common that they can be issued in large packages of instruments with identical terms (same issuer, same maturity, same interest rate, same frequency of payment etc); as a result of being many and identical, they can be traded in secondary markets, feature that gives them the status of securities. Another group of financial instruments, such as loans, can be sold bilaterally to another investor but cannot be traded in a secondary market on the ground that they have quite unique features. They are NOT securities. Loans are indeed tailored to the needs of a particular borrower in terms of quantity lent, maturity date and interest rate reflecting their default risk; typically only one loan at a time is issued with these characteristics. As an organised market makes no sense for only one product, the sale of a loan to another investor can only be implemented via a bilateral arrangement.

The process of securitisation consists in structurally linking the stream of income of the new securities to the stream of income of the existing non securities. This is achieved by isolating the non tradable assets at the origin of the income for the new security as assets in a trust, called special purpose vehicle. That trust is also in charge of issuing as liabilities the new securities. Because of the link between the two streams of income , the new securities created through securitisation are generically called asset-backed securities (ABS in short) in this chapter. [1] Occasionally the name will be adjusted to reflect more precisely which assets have been isolated as a source of income; for instance if the assets are residential mortgage loans the new securities are referred as residential mortgage backed securities (RMBS). It is often said in textbooks or media that securitisation “transforms” “converts” an illiquid asset into a security, suggesting that the original asset disappears and is replaced; it is not strictly correct because the original assets actually still exist and have simply been relocated.

Securitisation fills two important purposes: firstly, it creates a new financial instrument for investors with an income coming from an asset in which these investors could not invest directly themselves (without a credit license one cannot have loans as investment for instance) and be able to easily get rid of it if desired thanks to an organised secondary market; secondly, it creates a way for the original investor, called the originator (the lender of the loans for instance), to get rid of the assets in the absence of secondary markets, therefore sparing the effort of having to find a buyer. These important benefits have been somehow forgotten, after securitisation of subprime mortgage loans was blamed for driving the global financial crisis that started in 2007 and securitisation reputation was tarnished as a result.

The most common type of securitisation in Australia is by far the securitisation of residential mortgage loans in the form of long term bonds issued domestically. The created bonds generate payment of coupons that are paid with the interest of existing residential mortgage loans. Among the assets that are securitised, i.e. structurally providing income to new securities, residential mortgage loans represent AUD 0.130 billions out of a total of AUD 0.162 billions, as of March 2022. The long term bonds created and sold domestically account for AUD 0.150 billions of the AUD 0.162 billions total asset backed securities. Even though these numbers have recovered after the GFC , they are nowhere near their levels of 2007, which was around AUD 0.270 billions in total. Currently the ABS on issue are the result of securitisation of assets issued by ADIs and non ADIs with relatively equal share.

The chapter has the following structure:

- The process of securitisation

- The benefits of securitisation

- The dangers of securitisation

1. The process of securitisation

1.1 The creation of securities backed by a reference portfolio

We explain the process of securitisation using the example of securitised assets that were originated by a company that is NOT a bank, to avoid the complications due to banks’ balance sheets working in a special way (Chapter 3 and 4). Think of a non-bank lender, a finance company for instance, wishing to securitise a group of its auto loans or its residential mortgage loans. The originator, the finance company, identifies the pool of assets to be securitised and approaches a trustee, usually an investment bank, to create a special purpose vehicle. The special purpose vehicle, usually referred as SPV for short, is a separate legal entity that is insolvency-remote from the originator, meaning that it has its own balance sheet, independent from the balance sheet of the originator. The trustee in charge of managing the SPV must not be related to the originator so cannot be a subsidiary of the originator. Each securitisation requires its own SPV.

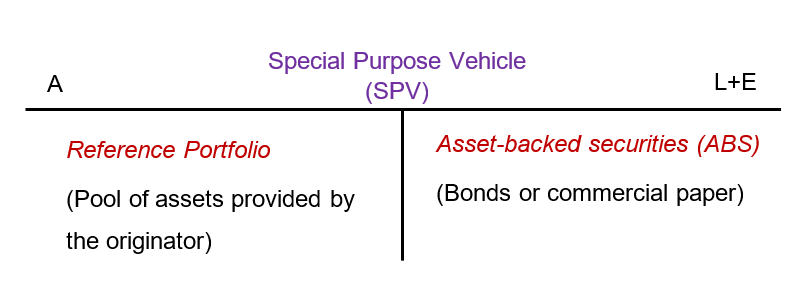

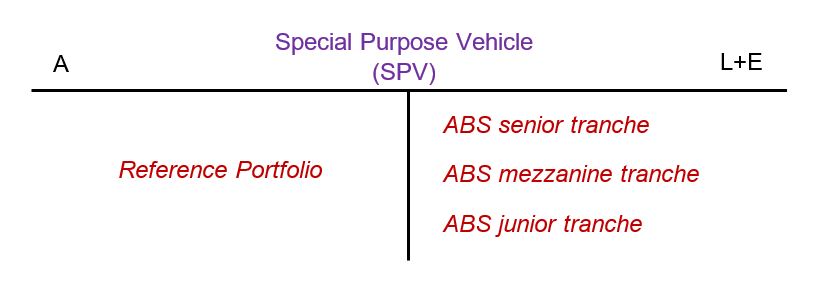

The securitised pool of assets that is taken away from the originator appears as assets for the SPV; it is called the reference portfolio (or receivables) as it is the portfolio providing the income; the SPV is now the official owner of the assets and therefore is entitled to receive the income (interest for loans) generated by these assets. The SPV is the issuer of the new securities in its liabilities side, the asset-backed securities. “asset backed” refers to the fact that the income of the new security is coming from the income of other assets, those in the reference portfolio. The SPV balance sheet looks like the following:

It is clear from the SPV balance sheet above that both types of financial instruments co-exist at any time and that there has not been any replacement of one by the other or transformation of one into the other. Be aware of many mistakes circulating in resources in the Internet that, certainly by lack of understanding of accounting, wrongly take reference portfolio and asset backed securities as one single instrument. [2] It is true that the pool of assets in the SPV is now “stuck” in the SPV as they are now structurally linked to the ABS and therefore need to remain in the SPV as long as the ABS exist. The ABS circulate in the financial system as they are tradable in organised secondary markets.

The nature of the link between the two sides of the balance sheet is two-fold.

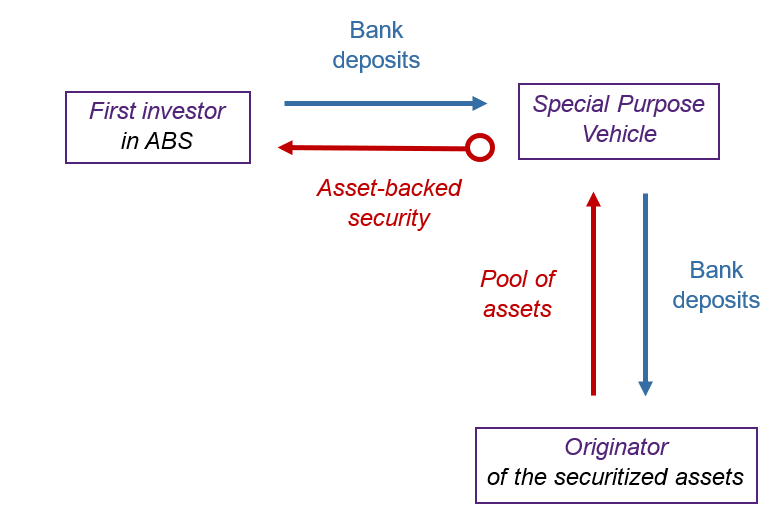

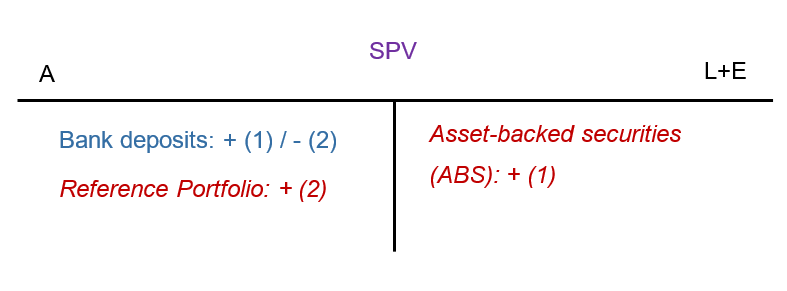

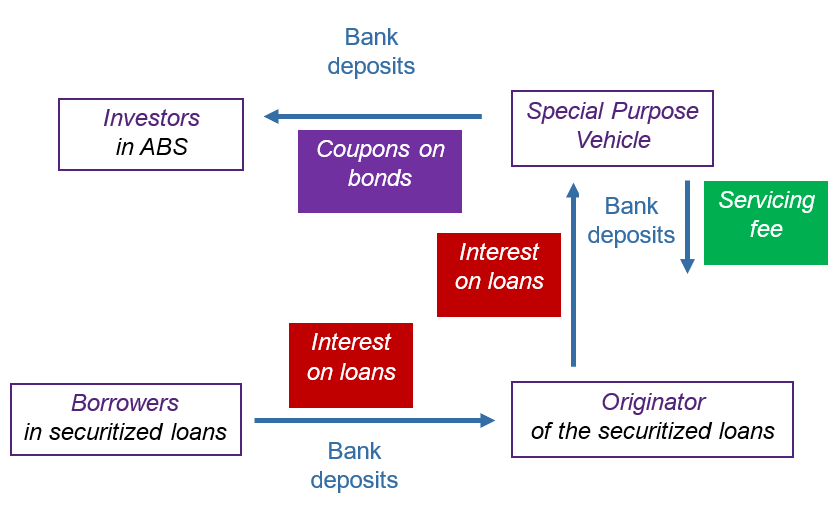

Firstly, the asset backed securities issued by the SPV, the new securities, are the source of funding for the purchase of the reference portfolio by the SPV from the originator. The investors who buy the ABS provides the funds that will be used to buy the reference portfolio. In the flow-of funds diagram below, the new instruments are symbolised with a circle, following the convention introduced in Chapter 1. Note that the reference pool assets do not exhibit a circle as they already existed and are simply transferred from one investor (the originator) to another investor (the SPV).

To avoid complications we assume that the issue of ABS takes place before the purchase of the reference portfolio so that the SPV has the money to buy them. However, the issue of the ABS requires to have very precisely identified the assets in this portfolio so the volume of ABS, their coupon rate and their maturity can be defined and overall match the income and maturity of the reference portfolio. [3]

Secondly, the reference portfolio income is the source of the income paid by the asset backed securities to the investors. For instance if the securitised assets were loans and the asset-backed securities were bonds, the interest on the loans would pay the coupons on the bonds. As it would be too complicated to ask borrowers to pay directly the SPV, the originator accepts to keep collecting the interest on the loans on behalf of the SPV and pass them to the SPV in exchange for a servicing fee. Borrowers may not even notice that their loans have changed hands.

Depending on what assets are securitised the source of income for the coupons will be different. In the diagram above the interest from the loans are used to pay the coupons of the new bonds. The source of income would be lessees’ payments if the securitised assets were car leases; the source of income would be royalties if the assets were intangible intellectual property rights, as the royalties on David Bowie intellectual property rights on his music that were securitised as 10 year bonds in 1997.

There are some rare cases where the securitised assets are already securities themselves such as bonds. In that case the coupons of the original bonds are the source of the coupons for the SPV’s created ABS.

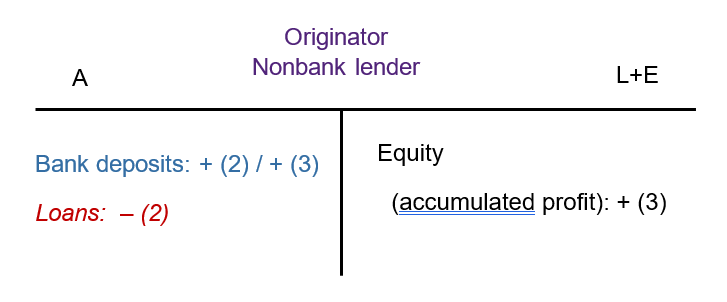

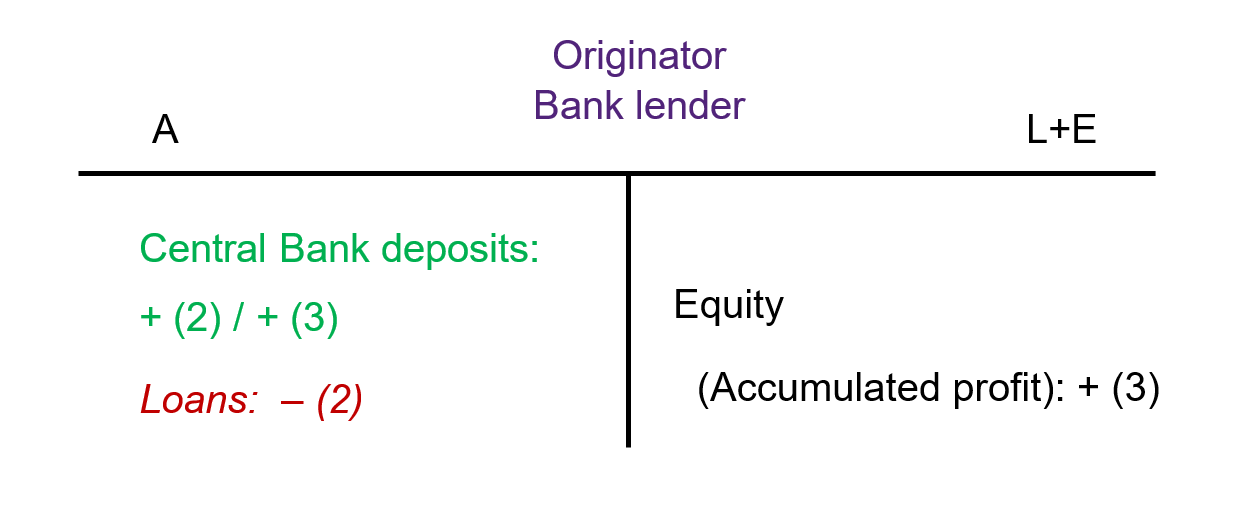

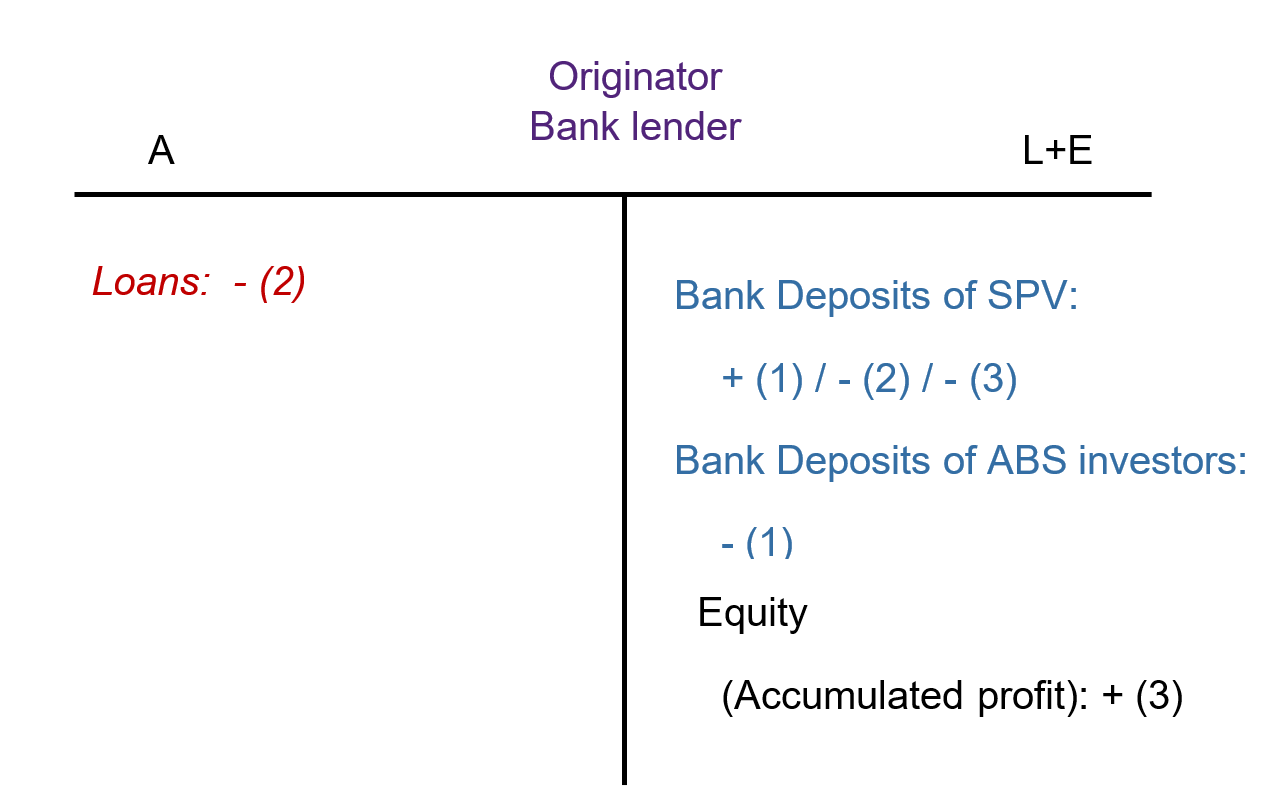

For the originator, the non-bank lender, the securitisation process has two consequences: the originator loses the pool of assets and receives bank deposits in replacement (2). The payment of the servicing fee is an income for the originator that boosts its equity (accumulated profits component) and its bank deposits (3). The effects on the originator’s balance sheet are represented below.

When the originator is a bank, the sale of the pool of securitised assets cannot bring bank deposits to the bank’s assets, as we explained in Chapter 3. The reason is that by definition of an ADI, bank deposits in domestic currency can only be liabilities for them. The effect of securitisation for the bank would be an increase in central bank deposits or no variation of money at all. See Appendix for the details of the cases where the originator is a bank.

1.2 Tranches of asset-backed securities

In the early days of securitisation, the SPV used to issue homogenous ABS, with the same characteristics: the same coupon or interest rate, and the same priority rank. When some assets in the reference portfolio were defaulting in paying interest and/or principal of the loans all ABS investors were affected the same way, i.e. receiving the same fraction of the promised coupons and the same fraction of the face value at redemption.

An important innovation in the securitisation industry, however, consisted in SPV issuing ABS in tranches with differentiated features. Let’s assume three tranches of ABS: the senior tranche, the mezzanine tranche and the junior tranche. There are instances where the number of tranches is much higher, as was the case for a Firstmac RMBS deal in 2020 with seven tranches.

All ABS of a given tranche remain identical but are different from the ABS of another tranche, with a different coupon rate and a different order of priority (subordination) in the payment from the reference portfolio income. In the case of ABS in the form of notes, the interest payment takes the form of a variable rate and each tranche may have a different margin over the BBSW rate.

Although the liabilities of the SPV are sliced, the reference portfolio in the asset side remains one single entity from which the interest paid are pooled together. When the reference portfolio fully pays the promised interest, i.e. when none of the borrowers defaults, there is by design enough income to pay all the ABS tranches coupons so the ranking does not really matter. However, if some of the borrowers default, there is not enough income from the pool of assets to pay all investors and the order of payment is then crucial.

The allocation of assets income operates like a waterfall, whereby the interest from the reference portfolio fill up the requirement of an upper tranche fully before flowing down to the next tranche and so forth. The senior tranche investors are paid first; the mezzanine tranche investors are paid only after all investors in the senior tranche have been fully paid and finally the junior tranche is paid last. Being paid last means having the highest probability of default; as a compensation for the higher credit risk, the junior tranche offers a higher coupon rate. On the contrary, the senior tranche has the lowest probability to default as it is served first and as a consequence pays the lowest coupon rate. The mezzanine tranche offers an intermediate coupon rate as it has a probability of default between the two other categories.

All investors in a given tranche must be treated the same way: if there are not enough interest from the reference portfolio to serve the promised coupon for all ABS in that tranche, all investors in that tranche will be rationed applying the same ratio. Consider the example below where $250,000 interest from securitised loans match the $250,000 promised coupon payments to the ABS investors. There are enough for each tranche to receive the full promised coupons. However, in the case where the interest are only $160,000 as $90,000 interest are missing, the senior tranche could be fully served but the mezzanine tranche only get $100,000 instead of $150,000 needed; all investors in the mezzanine tranche receive 2/3 of their promised coupons. 2/3 is obtained by calculating 100,000/150,000. As there is not enough to serve the mezzanine tranche, the junior tranche receives nothing.

| Liabilities (in $) | Coupons promised (in $) | Allocation of interest from loans (in $) | Allocation of Interest from loans (in $) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 9,000,000 | 250,000 | 250,000 | 160,000 |

| Senior | 3,000,000 at 2% | 60,000 | 60,000 | 60,000 |

| Mezzanine | 5,000,000 at 3% | 150,000 | 150,000 | 100,000 |

| Junior | 1,000,000 at 4% | 40,000 | 40,000 | 0 |

With tranches a relatively low quality reference portfolio can still give rise to low default asset backed securities for the senior tranche, by directing the few payment of interest to that tranche in that tranche. In contrast, the junior tranche will always have a probability of default larger than the reference portfolio of securitised assets, by design.

Credit rating agencies are paid to assess the risk of the securitised assets, design the size of the three tranches of ABS and rate them accordingly. The introduction of tranches has significantly complexify the task of rating ABS and credit rating agencies request higher fees for providing this service.

The purpose of securitisation is to create a security, i.e a financial instrument that can be exchanged among investors in an organised secondary market. The ABS issued in Australia are usually traded over the counter through a dealer. Investors can acquire or get rid of their ABS at any time in that market.

1.3 Credit Enhancement

Credit enhancement refers to processes that permit credit risk borne by the ABS investors to be smaller than the credit risk on the assets in the reference portfolio.

There are three internal structural mechanisms that result in credit enhancement for ABS holders.

Using tranches is a way to do credit enhancement for the investors choosing the senior tranche as by design the rating of the senior tranche is higher than the rating of the reference portfolio. However, there is credit deterioration for the junior tranche as by design the rating is worse than for the whole reference portfolio.

Over-collateralisation is another way to protect the ABS investors by guaranteeing that the actual value of the assets is higher than the value of the ABS (creating a non rated equity layer below the junior tranche) and that the stream of income from the reference portfolio is larger in value than the promised coupons. It means that in case of default, it will not hit the junior tranche investors at once.

Another way is to require from the originator to provide a reserve fund of bank deposits that can be used to pay coupons on ABS if there is not enough interest payment from the pool of assets or if the face value redemption of the ABS cannot be covered entirely with the repayment of principals of the loans.

There are also two external mechanisms to implement credit enhancement.

For residential mortgage backed securities, the SPV can take a mortgage insurance that cover the loss if the property value is not enough to repay the loan when it defaults. The cost of insurance will result in offering lower interest rates on ABS.

In some cases, a guarantor (an insurer or sometimes the originator itself) commits to pay any shortfall of income from the assets. This system is not often used in Australia.

2. Benefits of securitisation

Securitisation got bad press after it was blamed for being a key driver in the subprime mortgage crisis that led to the global financial crisis. Nevertheless, one cannot overlook the useful role it plays in the financial system. We give an overview of the benefits for the various parties involved.

2.1 Benefits for the originator

The vast majority of assets in finance companies and banks are loans, for which there are no secondary markets. Should the lenders need or wish to get rid of loans from their balance sheets, they have either the option to arrange bilateral deals with another lender to transfer the loans to them or to securitize them. It is easier to do so by securitisation rather than to find direct investors. The originator initiates the process and the SPV is created to automatically buy these assets without having to look for a buyer. The SPV of course will have to find investors to the ABS.

The motivations to get rid of a pool of loans can be various: it could be due to the desire of the bank and non-bank lenders to rebalance the portfolio away from a certain type of loans in favour of new assets and/or to decrease credit risk. Indeed, through securitisation, the credit risk associated with these loans is removed from the balance sheet with the sale of the loans to the SPV and transferred to the ABS investors. Of course if the originator were to invest in ABS the credit risk would come back to its balance sheet. [Note that when an originator proceeds to self securitisation, i.e, buys all the ABS issued by the SPV, the motive is not to decrease credit risk currently but to keep the opportunity to do so easily in the future due to the secondary market for ABS].

For banks, which unlike non bank lenders are subject to capital regulation, securitisation can decrease their risk weighted assets (RWA). In the calculation of RWA, loans appear with a positive weight while central bank deposits are assigned a zero weight; therefore a swap of loans for central bank deposits necessarily decreases the risk weighted assets. As regulatory capital requirements for banks are calculated as a percentage of their RWA, removing the loans results in lowering capital requirements. This could be useful if the bank was struggling to meet the requirements due to losses. [See chapter 8] They could be true also by substituting other lending with a lower weight than the securitised assets’ weight.

Another benefit that is reported in the literature is that originator match-fund its assets, i.e. fund assets with liabilities that have the same lifetime, reducing refinancing risk. One way to interpret this benefit is that the originator gets rid of assets that are not matching the liabilities in the portfolio and replace them with assets that are more suited to the current liabilities.

The originator replaces an uncertain interest income flow from the loans by a certain income flow from servicing the loans. This is an alternative business model generating income from originating and servicing loans but not keeping the loans. In the case of a finance company that needs bank deposits to make new loans, the sale of the loans brings bank deposits that will be available for further lending: securitisation provides liquidity for the next round of loans for the originator, without the need to contract new liabilities. [This argument is not relevant for banks as securitisation may not bring central bank deposits and making loans does not require losing money anyway, since the loans create the deposits that are lent, as described in details in Chapter 3 and 4]. The finance companies that adopt that business model register a growth in servicing fees they earn as they originate and securitise loans in a continuous way.

It is sometimes noted that securitisation is a cheaper source of funding for the originator than issuing new liabilities in its balance sheet. The coupons paid on ABS reflect the quality of the reference portfolio: the higher the credit risk of the reference portfolio the higher the coupons on ABS. If instead of securitising the originator had to issue new liabilities in its own balance sheet to get funds (argument only valid for finance companies, not for banks) the coupons of its liabilities would reflect the quality of all its assets, so a wider portfolio than simply the reference portfolio. If the quality of the reference portfolio is better than the overall assets, then getting the funds would be possible with a lower coupon rate. The author sees a flaw in this argumentation as the issue of ABS never appears as liability for the originator, and therefore do not constitute a source of funding for the originator as such. The argument would only make sense if we were considering the SPV and the originator as one merged identity, which is not satisfactory since they are two separate legal entities.

2.2 Benefits for ABS investors

ABS investors receive income from loans, while they are not able to invest directly in loans as they may not have a credit license. That allows them to be exposed directly to the return from housing mortgage from instance or small business loans.

Why is it better than investing in any liabilities or shares issued by the lender directly that would also give them exposure to lending? By buying securities issued directly by lenders, the investors would be exposed to the whole portfolio of the lender, not simply a subset of assets, and also be exposed to its other activities not related to lending. In the case of securitisation, investors are exposed only to a subset of loans that have some commonalities, such as loans for residential mortgages or small business loans in a certain sector etc. and are not affected by the other parts of the business of the originator thanks to the insolvency remoteness of the SPV from the originator. Investors through ABS can therefore target more precisely the type of exposure to lending than they have compared to the case where they would simply invest in a liability of the originator. If the other parts of the lenders go sour, ABS investors are not affected as the income comes only from the pool and this income cannot be claimed by the creditors of the originator.

While choosing to which loans they want to be exposed, investors in ABS can also choose the level of risk they wish to take by choosing the tranche that is the most suitable for their taste for risk. If they are risk averse they can choose the senior tranche whereas of they are risk lovers they are likely to select the junior tranche that offers a higher coupon rate.

Finally, and not the least, securitisation allows investors to be exposed to the loans but to have a security that has a secondary market and can be traded at any time. They can easily get rid of the investment if they wish. That is why the main investors would be managed funds, insurance companies, superannuation companies and even banks.

2.3 Benefits for the financial system

Instead of the credit risk being concentrated in one lender, and make that lender vulnerable, the risk is spread among possibly many different investors.

With investors happy to provide funds in exchange for ABS that they would perhaps not invest otherwise in the lenders directly, there are possibly more funding available for lending. That argument, however, is only valid for non bank originator; banks as we have shown in chapter 3 do not need funding to make loans since the loans create the deposits that are lent.

3. Dangers of securitisation

The dangers of securitisation have been highlighted during the subprime mortgage crisis. For each of them we describe the nature of the danger in generic terms and then we illustrate it using the subprime mortgage crisis, and the change in regulation that has been implemented to address that issue.

3.1 Increased adverse selection and moral hazard

In the case when the originator knows from the start that it will not keep the loans (following the business model of originating and securitising rapidly) and is not the one bearing the credit risk, the originator has an incentive to lend to a vast number of lenders, without pricing properly the risk: the originator has an incentive to charge lower interest rates than what the probability of default would require to keep a large demand for loans by borrowers and would lend to borrowers with a high probability of default. There is definitely an incentive to not screen out the bad borrowers, which is what we call adverse selection. There is also no incentive to monitor the behaviour of the borrowers during the loan life as the servicing fees will be the same even if the borrowers default; for the same reason there is no motivation to impose the closure of the loans when they default to keep getting the servicing fees from the SPV. That is a moral hazard issue.

That is exactly what what observed in the years leading to the subprime mortgage crisis. Many US lenders, mostly non bank lenders, adopted the model of ‘originate and securitise’ and indeed provided mortgage loans to low quality borrowers, whose probability of default was very high, hence the name of subprime mortgage loans, basically junk mortgage loans. The borrowers managed to get mortgage loans without providing evidence of stable income; households with no income, no job and no asset could get a loan, and these loans were humorously referred to as NINJA loans; in some cases, the lender voluntarily misrepresented the level of risk of the borrower in the application by reporting fake numbers. The house being the collateral for the loan and the housing market being in a boom there was also the reassurance that should the borrower default the increase in the value of the confiscated house would be sufficient to pay back the loan.

Borrowers could not afford to repay the loans once the teaser rate was abandoned at the end of the honeymoon period and the rates increased. The missed interest payment structurally affected the coupon payment on RMBS, affecting the junior tranches first and slowly hitting also the senior tranches.

A response from the regulator after the subprime mortgage crisis was to force originators to keep “skin in the game”, by buying some of the ABS securities. This way, the originator has an incentive to adopt good lending practices.

3.2 Challenging rating of the tranches

The division of the ABS in tranches represented a much more complex task for credit rated companies (CRA), which made mistakes in their assessment. The inability to price risk was obvious during the financial crisis. There were instances of AAA rated senior RMBS tranches defaulting!

In addition to possibly a problem of lack of skills of CRA analyst for dealing with a complex , some have argued that being paid by the rated could create a wrong incentive to please the rated and overrate the ABS, especially when they also conduct advisory job for their customer . This conflict of interest has since been mitigated with new regulations requiring CRA to separate completely the teams providing the rating from other activities of the company. They are also required to be consistent over time in the methodologies used for rating and to release information on the process that led to their rating decision. These two last requirements guarantee that the relevance of the rating can be checked by a third party and the CRA is accountable.

3.2 Wider spread in case of default and difficulty to locate it

Because the credit risk is spread, serious default would affect several investors. If the investors are managed funds, insurance companies or superannuation the problem then spread to more sectors. If the investors are foreign investors, the issues could spread to other countries.

It is more difficult to identify who will be affected and therefore to trace and predict the spread of the risk. That by itself constitutes a problem of adverse selection as not knowing precisely which investors are exposed to defaulting loans results in the suspicion applying towards more of them, punishing even those not actually exposed to that risk.

The difficulty to identify the exposure could be made even more acute with the practice that has been seen during the subprime mortgage crisis of a several successive securitisation where the ABS from several SPVs were themselves included in the reference portfolio of new ABS. It was nearly impossible to trace where the income was originated for these securities and rating were more complex to implement.

3.3 The SPV are not regulated

Unlike banks, SPV are not subject to capital requirements when holding loans. The SPV holding loans that are traditionally held by banks are therefore part of shadow banking.

4 Conclusion

We have shown that securitisation is useful to the financial system, even though that practice presents some dangers. The Australian government has recognised the importance of securitisation for the financial system and in particular for non-bank lenders. During the global financial crisis and again during covid-19 crisis, securitisation was slowing down by lack of interest from investors and the government saw this as creating a shortage of loans from lenders to small and medium enterprises (SME) compromising the economy health and the level of competition in the lending industry. The Australian government has tried to keep securitisation alive during the GFC by asking its agency AOFM to buy AAA rated ABS backed by loans originated by small lenders, including non ADI lenders, to SME for $20 billions program. By so doing the government was substituting itself to the investors that had abandoned the market. During the covid-19 crisis the government again supported the industry by creating a Structured Finance Support Fund (SFSF) of AUD15 billion through which AOFM, bought ABS backed by loans made to small and medium businesses.

5. References

Australian Securitisation Journal (2011-2022) semi annual publication by Australian Securitisation Forum

Goumenis, S. and Jinks, A. (2020) Structured finance and securitisation in Australia: overview from Clayton Utz for a study of Thomson Reuters Practical Law Website link

6 Appendix: When the originator is a bank

When the originator is a bank, the sale of the pool of securitised assets cannot bring bank deposits to the bank’s assets, as we have studied in chapter 3. The effect of the bank assets depends on whether the SPV and/or investors in ABS have an account in this bank or another bank.

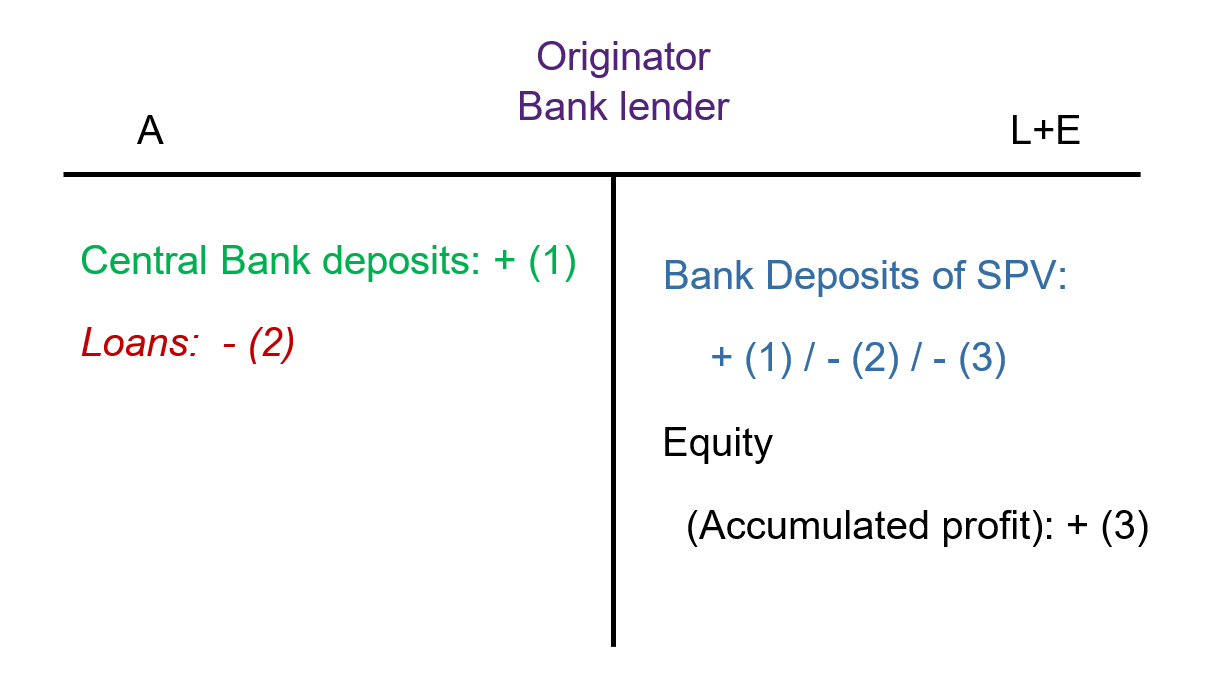

The first case we study is the configuration where both the SPV and the ABS investors have an account in another bank. In that case, the sale of the loans brings central bank money, transferred by the bank of the SPV while decreasing the balance in the SPV transaction account.

The second case is the case where both the SPV and the ABS investors are customers of that bank. The difference with the previous case is that now the central bank deposits are not increased as a result of the securitization but instead the bank deposits managed in the liability side of the bank decrease.

The third case is the configuration where the SPV is a customer but the ABS investors are not. The sale instead decreases the bank deposits of the SPV, assuming the SPV has an account in the securitising bank, therefore affecting the originator’s liabilities. The funds that the bank would get is central bank deposits: when the ABS investors pay for the new securities they transfer bank deposits to the SPV triggering their banks to transfer central bank money to the securitising bank.

Note that in that case the money is acquired during the issue of the ABS rather than during the sale of the pool of securitised assets. See in Appendix all the other configurations, leading to no central bank money being raised at all. The servicing would increase the bank equity and either decrease the bank deposits of the SPV if banking in the same bank or increase the amount of central bank money if the SPV was banking in another bank.

We let the reader study the case where the ABS investors are customers but not the SPV. The conclusion will be that the central bank money decreases and then increases resulting in no change in net. Of course there are also cases where some ABS investors are customers while other investors are not.

In all cases, the effect on money is different and securitisation therefore cannot be described as a sure source of money for the originator, unlike for a non bank lender.

- Note that in this chapter we use ABS as the general term that embeds all possible securitisation products. Be aware that ABS is often used in the media as being not a general term but a subcategory of these products that excludes residential mortgage loan backed securities (RMBS) or commercial mortgage loan backed securities (CMBS). ↵

- In an Investopedia's article Chen incorrectly confuses both sides of the balance sheet when he wrote " Often the reference portfolio—the new, securitized financial instrument—is divided into different sections, called tranches" https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/securitization.asp accessed on 31st march 2022. ↵

- To keep our story simple we ignore here that a line of credit may be provided to the SPV to acquire the reference first. Once the ABS are issued the SPV can repay the line of credit. ↵