16 Indigenising and decolonising the curriculum in a business school

Sharlene Leroy-Dyer; Samantha Cooms; Gemma Irving; Jonathan Staggs; Lisa Ruhanen; and Sean Mitchell

UQ Business School

Introduction

UQ Business School (UQBS) is an advanced signatory to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME), which commits the School to embedding the UN sustainable development goals, including co-designing and co-creating learning environments and opportunities with our students that support experiential learning related to ethics, responsibility, sustainability and the global goals. A key outcome of this is to increase the use of pedagogies and knowledge frameworks from diverse worldviews, including Indigenous perspectives.

Given both The University of Queensland (UQ) Stretch Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) and the PRME goals, a strategic priority of the Business School is to develop our capacity to Indigenise the School’s curriculum, with the goal that 25% of the School’s courses will have Indigenous perspectives embedded by 2032; this is in line with the PRME objectives and UQ’s horizon for strategic planning (UQ, n.d.). With almost one in four UQ students studying across one of the Business School’s 13 undergraduate or postgraduate coursework programs, UQ Business School is well positioned to make a significant and impactful contribution to UQ’s Indigenising curriculum objectives.

The UQBS Indigenising the curriculum project is based on five key criteria.

- Place-based: Aboriginal peoples and knowledge systems primarily in focus are the South East Queensland Aboriginal peoples

- Indigenous knowledge-based: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander scholarship and expert Indigenous voices are prioritised, helping students learn from, rather than about, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- Partnership-based: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous academics collaboratively and equally share content development and teaching

- Progression-based: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content is built to form a coherent body of knowledge across courses

- Experientially based: students directly engage with Indigenous knowledges, which includes guided on Country experiences.

The Indigenising the curriculum project is a long-term, strategic innovation and a key part of the teaching and learning domain of the UQBS strategic plan. In the context of business education, Indigenising the curriculum is essential in signalling to students that Indigenous-related content and perspectives are important in learning about business. By integrating Indigenous material throughout the curriculum, academics can shift the expectations of students and teachers regarding the intellectual boundaries of their fields of study (Gainsford & Evans, 2017; Maguire & Young, 2015). Moreover, the development of case study examples and contextualised cultural content for all disciplines in business is essential to provide resources for academics and students to critically explore the often unexamined Western assumptions underpinning business education. Further, integrating discipline-specific content into the business curriculum acknowledges the importance, value and relevance of Indigenous content in industry learning (Gainsford & Evans, 2017).

Authors’ positionality

Sharlene Leroy-Dyer is a saltwater woman, with family ties to the Dharug, Awabakal, Garigal and Wiradyuri Nations. Sharlene was the first Aboriginal academic to gain a PhD from the University of Newcastle Business School. She is the inaugural Director of the UQ Business School Indigenous Business Hub. Sharlene’s positionality as an Aboriginal scholar informs her research work in academia. Her current research areas include closing the gap on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander disadvantage in education and employment, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander labour history, and Aboriginal involvement in the trade union movement.

Samantha Cooms is a Noonuccal woman of the Quandamooka people and a Senior Lecturer at UQ Business School. Her positionality as an Indigenous scholar informs her approach to research, teaching and engagement, grounding her work in relational, decolonial and Indigenous methodologies. With a disciplinary background spanning management, Indigenous studies, psychology and disability research, she centres Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing in all aspects of her practice. As a single mother and carer of children with disabilities, Dr Cooms’s lived experiences also shape her commitment to research that advances equity, cultural safety and Indigenous self-determination. She approaches her work with a strengths-based lens, aiming to create spaces where Indigenous knowledge systems lead and where relational accountability is upheld across research, policy and practice.

Gemma Irving is a non-Indigenous Senior Lecturer at UQ Business School. She currently lives on Turrbal Country in Brisbane, Australia. Gemma is passionate about helping students build connections with each other, the UQ campus and their own curiosity, including by engaging with Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing. Her research on organisational space, hybrid work, professional work and learning informs her approach to teaching.

Jonathan Staggs is a non-Indigenous Lecturer at UQ Business School. He grew up on and currently lives on Jaggera Country in Brisbane, Australia. In 2003, Jonathan won a Brisbane City Council local history grant entitled Our Sunnybank to help profile the deep Indigenous connection with water and food sources. Jonathan is passionate about helping students develop a stronger awareness and connection of place and to leverage UQ’s facilities to improve their understanding of Indigenous ways of being. Jonathan’s research on place-based entrepreneurship and innovation informs his approach to teaching, and vice versa.

Lisa Ruhanen is a non-Indigenous academic who grew up on, and is now raising her family in, Meanjin. She has worked for more than a decade with First Nations businesses and communities on tourism development opportunities. She contributed to the development of Queensland’s inaugural First Nations Tourism Plan and is co-chair of the Queensland First Nations Tourism Council Research and Innovation Hub where she regularly engages with businesses on tourism projects and initiatives. She also supports the UQ Business School’s Indigenising the curriculum program.

Sean Mitchell is a non-Indigenous Learning Designer at UQ Business School. He currently lives and works on Turrbal and Jaggera Country in Brisbane, Australia. Sean’s positionality as a non-Indigenous professional informs his commitment to supporting Indigenous voices and perspectives in business education. Drawing on a background in curriculum design, innovation and digital learning, Sean collaborates with Aboriginal and non-Indigenous colleagues to create culturally responsive and engaging learning experiences. Through his practice, Sean aims to foster environments where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being and doing are meaningfully embedded in the student experience.

Including Indigenous knowledges and perspectives in UQ Business School curriculum

Including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges and perspectives in business school curricula within tertiary institutions is recognised as a key strategy to improve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander student participation, retention and success in business degree programs in Australia (Altman et al., 2017). Further, the President of the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC), Professor David Grant, said the 39 university business schools across Australia “need to more actively engage with Indigenous communities to better understand their needs and expectations of business and business education” (ABDC, 2019).

In 2021, Dr Sharlene Leroy-Dyer and Professor Lisa Ruhanen applied for a UQ Teaching and Learning Grant to assist in kick-starting the Indigenising of the curriculum process. This grant supported the employment of an Aboriginal learning designer in the Business School. The Indigenising the curriculum initiative to date has focused on ensuring new programs, and significant program or curriculum redesigns, embed Indigenisation of the curriculum in the design and planning phases. The team has also worked alongside non-Indigenous course coordinators, supporting these academics to engage in course-level Indigenisation of the curriculum through mentoring and the establishment of a community of practice. In addition, the team developed and curated teaching and learning resources for inclusion within the School’s programs, courses and curriculum.

Recognising that there are few successful examples of Indigenising curricula in tertiary-level business schools in Australia or internationally, and that this learning journey requires the buy-in of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics, the team have focused on awareness, understanding and relationship building, initially working closely with several course coordinators to embed Indigenous knowledges and perspectives into a small number of courses. Through this process, we learnt many lessons and identified how we could attempt to scale this mentoring and support across the 200+ courses offered within the School. Importantly, by building the initiative gradually, we were able to create allies and champions who can offer support and mentorship to other colleagues.

For example, Indigenising an undergraduate introductory management course not only led to exceptionally positive student feedback and learning outcomes, but the course coordinator has become an important champion and contributor to the School’s Indigenising the Curriculum Community of Practice. This story forms an important contribution to this chapter, which is outlined below in example 1.

Our learnings at the individual course level also supported the move to Indigenising the curriculum of entire programs. For example, as part of the School’s MBA program review, the team worked collectively with academics across the suite of MBA courses, which has resulted in an innovative approach to program and curriculum development that places Indigenous perspectives and knowledges at the core of the curriculum. Additionally, the School developed a Master of Finance and Investment Management (MFIM) accelerator program in conjunction with industry, which afforded a unique opportunity to embed Indigenous knowledges and perspectives into a brand-new program. MFIM is designed for experienced professionals, generally working in senior positions in the industry, so each course is a blend of online learning and face-to-face workshops, creating a unique learning experience for the participants while creating challenges for the Indigenising team in not only developing blended content, but aligning this with the program and course-level objectives. Like the MBA, the team collaborated with academics involved in developing the MFIM program and continues to engage in iterative development, focusing on gaining buy-in from the academic teams to support the Indigenisation of the courses. The Indigenising the curriculum initiative is multidimensional, and we focus on evidencing outcomes from two particular aspects.

Firstly, we have seen students positively respond to the Indigenisation of the curriculum in undergraduate and postgraduate courses enrolling large numbers of both domestic and international students. We identified multiple opportunities to integrate Indigenous perspectives, incorporating Indigenous case studies and concepts at key points throughout the course. Transforming the curriculum has resulted in a remarkable increase in student satisfaction, with evaluation scores rising from an average of 3.5 to 4.5. This shift has demonstrated not only the effectiveness of the approach, but also the value students place on an Indigenised business curriculum.

A second outcome has been the building of a vibrant Business School Indigenising the Curriculum Community of Practice. Launched in 2024, the community of practice has seen more than 25 engaged and passionate academics and learning support staff who regularly attend our monthly sessions. These gatherings provide a space for non-Indigenous academics to learn, share experiences, discuss challenges, and confront knowledge gaps together, as well as with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander colleagues. In this collaborative environment, we are collectively reimagining the business curriculum to reflect Indigenous perspectives in a meaningful and respectful way.

The next section of this chapter will highlight two examples of how Indigenising the curriculum in the Business School has led to collaborative outcomes and important learning experiences.

Example 1: Indigenising the Grotesque Quest in Introduction to Management (Gemma Irving, Sam Cooms, Sean Mitchell)

Our first example involved bringing Indigenous representation into an activity called Grotesque Quest. Gemma (non-Indigenous Course Coordinator) and Sean (non-Indigenous Learning Designer) originally designed Grotesque Quest as a scavenger hunt of UQ’s Great Court to help first-year Introduction to Management students make friends, get oriented to campus and experience management concepts in their first few weeks at UQ. In 2024, we reached out to Samantha (Sam) Cooms (Mirigympa/Mara Jahlow Noonuccal Jandawal, Lecturer in Management) for support to integrate carvings that represented Aboriginal people into the activity.

Sam and Gemma had been working together to decolonise and Indigenise Introduction to Management since 2023. At the time, enrolments were approximately 1,000 students per semester, and most students were in their first semester of study and approximately 40% were international students. The course introduced students to the four functions of management: planning, controlling, leading and organising. Initial feedback on efforts to Indigenise the course were positive, with most students indicating they are either supportive (61%) or neutral (22%) about the inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in future offerings of the course.

The learning activity

We delivered Grotesque Quest across 40 tutorials scheduled from Monday to Friday in Week 3 of the semester. The location for the quest was UQ’s Great Court, a semi-circular quadrangle of buildings located at the heart of the St Lucia campus. The sandstone buildings feature numerous carvings, including the iconic grotesques. These are humorous stone projections of people connected to UQ, fictional characters, animals and mythical creatures.

The quest involved students working in teams to solve clues and locate QR codes in the Great Court. After scanning a QR code, students watched an AI-generated animation of a nearby carving posing a multi-choice question related to a topic in the course (see Shakespeare video example). Teams received points for a correct answer. The quest was an icebreaker, which provided students with insights into the history of UQ and gave them a practical experience of planning, controlling, leading and ethical decision-making to reflect on during the semester.

We selected carvings for the quest to represent the diverse people and intellectual traditions that have informed UQ’s history. This included academics and professional staff affiliated with UQ, such as the first principal of The Women’s College Dr Freda Bage, economist and government statistician Dr Colin Clark and UQ’s former head cleaner Mr Donald Russell, as well as internationally recognisable scholars such as Chinese philosopher Confucius, English playwright Shakespeare and French chemist Antoine Lavoisier.

Example animation of a Great Court carving

To represent the contribution of Aboriginal peoples, we consulted the Campuses on Countries Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Design Framework (Go-Sam et al., 2021) and the associated engagement report (Marnane & Bower, 2021) to identify carvings that were valued by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff and students. Through this process, we began to better understand the role of the Great Court in Queensland’s colonial history. For example, one participant in the Campuses on Countries study said, “Although I like sandstone, the imposing buildings that totally enclose the space and the motifs celebrating white colonial history don’t create a safe or inviting space” (Marnane & Bower, 2021, p. 28).

Our understanding was deepened by engaging with Carving a History: A Guide to the Great Court which explains that the carvings in and around the Great Court were intended to showcase “the social, economic and cultural progress Queensland had made” since the British invasion (Marketing and Communication, 2021, p. 13). As a result, carvings representing “Aboriginal customs and social life” including hunting, fishing and ceremonies were grounded in assumptions of European superiority (Marketing and Communication, 2021, p. 66). Problematically, they also depicted activities (e.g., seed grinding, tooth removal as part of initiation) with no connection to local Aboriginal traditions in Brisbane or even Queensland, perpetuating false ideas of a universal Aboriginality (Marketing and Communication, 2021).

In the context of a first-year management course, we felt it would be difficult to unpack the problematic elements of the carvings in a way that authentically connected with the course content. Instead, we decided to incorporate positive representations of Aboriginal peoples and perspectives into the quest. This aligned well with our broader approach to decolonising the course, which focused on drawing students’ attention to the colonial foundation of management while presenting a strengths-based view of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander business owners, leaders and entrepreneurs.

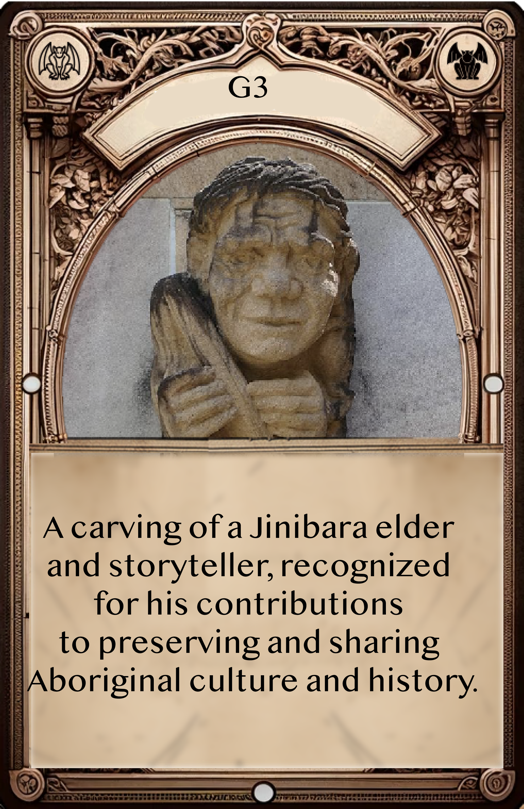

As a result, we chose to include two carvings representing Indigenous people and culture in the quest. The first was the grotesque of Gaiarbau (also known as Willie Mackenzie), which a participant in the Campuses on Countries research project described as “the most important Aboriginal site here [at UQ’s St Lucia campus]” (Marnane & Bower, 2021, p. 28). Gaiarbau was a Jinibara man and the first Aboriginal person to be recognised as a cultural authority at UQ. In the 1950s he worked with researchers at UQ to record Aboriginal music and stories from the Queensland area.

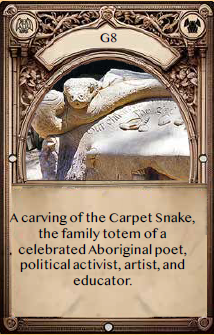

The second carving was the Noonuccal Totem Seat located at Wordsmiths Cafe. The stone seat features the carpet snake totem of the Noonuccal people of Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island) and lines from “The Song of Hope”, a poem by Oodgeroo Noonuccal (also known as Kath Walker). Oodgeroo was an award-winning poet and activist who campaigned for Aboriginal rights and against uranium mining. She was the first Aboriginal person to publish a book of poetry.

Gemma, Sean and Sam worked together to ensure Gaiarbau and the Noonuccal Totem Seat were appropriately represented in the activity. This involved several conversations about Aboriginal cultural protocols surrounding depictions of deceased people. For example, we spoke about whether there were specific local cultural protocols for depicting images and voices of the dead, as well as the more general idea of “letting the dead be dead”. These conversations helped us understand that it can be confronting for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to encounter archival footage or recordings of their forebears when they are not expecting it. This was a common experience for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who were often subjects of research and documentaries that they themselves had not designed. We decided it would be best practice to include a warning before the video stating “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that the following video may contain images and voices of deceased people”. While the original videos (Version 1) of Gaiarbau and the Noonuccal Totem Seat included animations (as we did for the other carvings), we changed this to a still image of the carvings with a slow zoom in and a voiceover.

We worked through other issues, such as including brief biographical information about Gaiarbau and explicitly crediting Oodgeroo Noonuccal when citing her poetry. We also discussed appropriate accents for Gaiarbau.

Although Sean suggested checking the final videos (i.e., Version 2) with Sam, Gemma was conscious of Sam’s time and felt confident that the videos were appropriate. She shared the final videos with Sam on the first day of the quest after they went live. Upon seeing the final video of Gaiarbau, Sam still felt something was not quite right. After sleeping on it, she reached out to tell Gemma that the use of first-person was inconsistent with the idea of “letting the dead be dead” and could be traumatising to Gaiarbau’s descendants.

In response, Gemma removed the QR code associated with Gaiarbau so that students could not access the video. Sean temporarily blocked the website hosting the video of Gaiarbau. He replaced the video with a photo and text describing Gaiarbau in the third-person. Once we all felt comfortable with the updates, we unblocked the website and replaced the QR code. As we were already working together to fix minor issues with the quest across the week, the website was fixed by the next day. Sharlene reached out to Gemma to debrief about what happened and to encourage the team to share our learnings.

Overall, Grotesque Quest was received positively by students, with around 70% of students suggesting they enjoyed the activity and 65% of students suggesting it helped them to make friends. As well as being a fun way of introducing new students to the contributions of Aboriginal people to UQ, it has created ongoing opportunities for reciprocity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous staff members. So far, this has included adapting the quest for the National Indigenous Business Summer School at UQ, using insights from the quest to inform a NAIDOC Week walking tour of the UQ campus and ongoing research projects about the process of Indigenising the course.

The iterative process for featuring the Gaiarbau grotesque in the Grotesque Quest activity is outlined below.

| Version | Description |

|---|---|

| Version 1

(draft) |

Text appears: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that the following video may contain images and voices of deceased people.

AI generated animation of Gaiarbau’s grotesque speaking: As a graduate of UQ you will create: a) wealth, b) a real world, c) a difference, d) change |

| Version 2

(live during first day of Grotesque Quest) |

Text appears: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that the following video may contain images and voices of deceased people.

Voice over a still image of Gaiarbau’s grotesque: As a Jinibara man, I was the first Aboriginal person to be recognised as a cultural authority at UQ. I worked on research projects in the 1950s to document Aboriginal music and stories. What will you create during your time at UQ? a) wealth, b) a real world, c) a difference, d) change |

| Version 3

(fixed on second day of Grotesque Quest) |

Text under photo of Gaiarbau’s grotesque:

Gaiarbau, also known as Willie Mackenzie, was a Jinibara man and the first Aboriginal person to be recognised as a cultural authority at UQ. He worked on research projects in the 1950s to document Aboriginal music and stories. What will you create during your time at UQ? a) wealth, b) a real world, c) a difference, d) change |

| Version 4

(revised for the next semester) |

Text appears: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that the following video may contain images and voices of deceased people.

Voice over a still image of Gaiarbau’s grotesque: Gaiarbau, also known as Willie Mackenzie, was a Jinibara man and the first Aboriginal person to be recognised as a cultural authority at UQ. He worked on research projects in the 1950s to document Aboriginal music and stories. What will you create at UQ? a) wealth, b) a real world, c) a difference, d) change |

Example 2: Deep Listening on Minjerribah (Sharlene Leroy-Dyer, Lisa Ruhanen, Jonathan Staggs)

In contrast to the scale of Grotesque Quest, which was delivered to 1,000 students each semester by predominately non-Indigenous academics, our second example, Deep Listening on Minjerribah, involved a small group of students engaging in a field trip to hear directly from the Quandamooka people. The field trip was organised by Dr Sharlene Leroy-Dyer and Jonathan Staggs, PRME colleagues from UQBS. Sharlene is Associate PRME Director for Indigenous Engagement, while Jonathan is Associate Director for Teaching and Learning within PRME. It was in these roles that they collaborated to imagine a field trip to Minjerribah that aimed to enhance students’ place-based learning as an introduction to Indigenous philosophies and to foreground listening as an overlooked pedagogy. Media Production Coordinator Cameron Morgan encouraged us to explore soundscapes and improve our capability to be firstly aware of our acoustic surroundings and then our capability to responsibly situate ourselves in what we heard (Ihde, 2012). Professor Lisa Ruhanen has a longstanding relationship with the Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation (QYAC) on Minjerribah through her Indigenous tourism work, as well as UQ’s memorandum of understanding (MOU) with QYAC.

Field trip context

Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island) is the second-largest sand island in the world and is located off the coast of Brisbane in Moreton Bay. Sand mining has come to an end on the island and the island is in post-mining transition that offers both opportunities and challenges around its future direction (Osborne, 2015). The Traditional Owners of Minjerribah are the Nunukul, Nughi and Goenpul clans of the Quandamooka peoples who hold native title over the lands and seas of this area (QYAC, 2018). The Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation (QYAC) is the Registered Prescribed Body Corporate (PBC) created under the Native Title Act 1993 to manage the recognised native title rights and interests of the Quandamooka peoples since July 2011 (QYAC, n.d.). UQ has a research facility on the island, Moreton Bay Research Station, which works closely with the Quandamooka people, and the UQ/QYAC MOU allows the undertaking of joint research and development projects on Quandamooka Country.

UQBS partnered with QYAC to provide 10 students the opportunity to engage in problem-based learning as QYAC continues to develop strategic opportunities on the island. Students from UQBS were invited to submit an expression of interest (EOI) to participate in this fully funded three-day field trip to Minjerribah. An initial field trip was conducted in November 2021, and consisted of five UQBS staff, being four academics from various disciplines, Professor Lisa Ruhanen (Tourism), Dr Jonathan Staggs (Strategy and Entrepreneurship), Associate Professor Robyn King (Accounting), Aboriginal academic Dr Sharlene Leroy-Dyer (Management), and professional staff member Cameron Morgan, and 10 UQBS students nearing the completion of their degrees. A second field trip was conducted in January 2024, which consisted of three UQBS academic staff (Professor Lisa Ruhanen, Dr Sharlene Leroy-Dyer and Dr Jonathan Staggs), professional staff member Cameron Morgan, and 10 UQBS students.

Orion and Hofstein (1994) argue that a number of student characteristics can contribute to the learning outcomes of field trips, which include the level and type of knowledge and skills, acquaintance with the field trip area, and psychological preparation. Prior to the field trip, we assisted students to psychologically prepare for the field trip by introducing them to an online module where the context of Minjerribah, as well as the challenges facing the island, are explained. Students who attended the field trip were able to prepare for some of the issues they would hear about through this pre-reading of historical perspectives, as well as contemporary perspectives including a description of the economic and cultural opportunities and challenges facing the island following the cessation of sand mining (Harward-Nalder & Grenfell, 2011; Osborne, 2015).

Students on both of these field trips had the opportunity to engage in dadirri (deep listening) (Ungunmerr-Baumann et al., 2022), as they learnt about the current opportunities and challenges for the island, its residents, and businesses, and to consider these through a variety of cultural, economic and political lenses.

Students were invited to listen to the stories of how the Quandamooka people have retained their distinctive culture and continuous occupation and cultural practices on Minjerribah. Students were welcomed to the island with traditional practices, such as a Smoking Ceremony, and they listened to oral histories passed down through dance and stories told at key geographical sites to understand how caring for Country continues today.

We also explored yarning during the field trip and then again in focus groups. Bessarab and Ng’andu (2010) argue that yarning is useful for building a connection and establishing a relationship of trust. Social yarning “is a significant pre-cursor and an entry point in developing connection and building a relationship” (Bessarab & Ng’andu, 2010, p. 42). By utilising social yarning in the first instance, the relationship shifts from expert to personal and enables real and honest engagement with the participants (Bessarab & Ng’andu, 2010). It also helps to establish identity, family, community connections, trust and mutual respect, which is vital in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. By exploring yarning, we expect to achieve a greater openness and comfort which aids in the gathering of accurate information, and might not otherwise be achieved (Walker et al., 2013).

One of the current opportunities and challenges on Minjerribah and caring for Country is around fresh water. Water sustains both the natural and human environment on Minjerribah and the sustainability of the island’s economy, including tourism, depends on the quality and quantity of water resources. These water resources, as material markers of place, are currently managed by Seqwater under the jurisdiction of the Department of Environment and Science. Hartwig et al. (2021) argue that water and water places are crucial to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ spirituality, yet Indigenous groups can face unequal access to water and the political processes that manage water. This field trip offered students insights into native title recognition of water rights within a multidimensional construct of place.

Students listened to how QYAC in conjunction with Minjerribah Moorgumpin Elders in Council Aboriginal Corporation (MMEIC) and the Land and Sea Rangers work together to protect the lands and sea Country in many ways, including taking part in cultural heritage management, environmental impact assessments, negotiating over developments, educating the public, and maintaining land and sea management responsibilities. These Indigenous knowledges of caring for Country offer alternative ways of comprehending the world that are deeply rooted in connection to land, community and spirituality (Kwaymullina et al., 2013; Martin / Mirraboopa, 2003).

Students were then provided with an opportunity to experience water as a multidimensional place construct (a framework for understanding a place as a complex entity composed of multiple, interrelated dimensions, rather than a single, static concept) for themselves with a deep-listening exercise at dawn at Bummiera (Brown Lake). Leaving our camp before breakfast, we took students to the lake where they went off individually to a place of their choosing and to listen. What became quickly apparent is that listening is not so simple and to be reflective of the soundscape is more difficult than to reflect upon what students could see in the landscape. These visits to the lake represented a place-based, dadirri methodology to shift from what we are learning on the field trip to how we are learning on the field trip. Field trips can tend to promote a visual understanding, or at worst a colonial gaze, of landscapes. Instead, we wanted learners to approach the field trip as listeners, building on the work of Gershon and Appelbaum (2018) who argue that “ocular understandings” dominate educational foundations. The field trip adopts a place-based, deep-listening approach that seeks to attune learners to the sounds of Minjerribah.

Dadirri is a word, concept and spiritual practice from the Ngan’gikurunggurr and Ngen’giwumirri languages of the Aboriginal peoples of the Daly River region (Northern Territory, Australia). Dadirri means “inner deep listening and quiet still awareness and waiting”. It allows the participant to be still and to connect. Dadirri offers a “gift for two worlds” (a “bridge” between Indigenous and non-Indigenous worlds) and signifies deep listening, deep reflection and deep self-awareness for Aboriginal peoples (Ungunmerr-Baumann, 2002). Atkinson (2002) describes dadirri as “a process of listening, reflecting, observing the feelings and actions, reflecting and learning, and in the cyclic process, re-listening at deeper and deeper levels of understanding and knowledge-building” (p. 19). The dadirri approach was introduced to the group by Dr Sharlene Leroy-Dyer, prior to the field trip taking place, as an Indigenous methodological approach that was conducive to field trips and engaging students in immersive experiences.

This immersive experience on Minjerribah offered students an opportunity to reflect upon the challenges they heard about firsthand from key Indigenous and rights holder representatives from QYAC and MMEIC. Our proposition is that learners will recognise there are no “quick fixes” or simple answers to the way rights holders negotiate the future of Minjerribah, and that learners will recognise the differences between Indigenous and Western epistemologies and ontologies (Harward-Nalder & Grenfell, 2011). The field trip and various site visits and rights holder interactions were aimed at providing learners with “troublesome knowledge” that may lead learners into “liminal spaces” (Page, 2014). The significance of this liminal space is that learners do not remain unaware of cultural differences or choose to reject the differences. The field trip reflections instead aim for learners to remain engaged in an attempt to master an understanding of cultural differences.

The role of place in listening is highlighted by introducing listening as the architecture of place and by suggesting that listening can promote imaginative spaces. Place is both empirical and phenomenological (Arnett, 2019), in that we can remember specific details of places we visit and we can remember how our identity is transformed in places in time. Arnett (2019) points to the role where imagination responds to the real and anticipates what is not yet, “expanding into a phenomenological territory well beyond its origin” (p. 185). Building on these philosophical insights, the field trip aims to provide an “expanding, imaginative sense of space”, “moving from mere acquisition of information to an enlargement of human life” (Arnett, 2019, p. 187).

The field trips aimed to inform how a pedagogy centred on place-based, deep-listening perspectives may help support students in problem-based and self-regulated learning. The outcome of this project will contribute to the widespread adoption of place-based perspectives and deep-listening skills to support students when they are faced with challenging scenarios in an increasingly diverse workforce, and with “wicked problems” in the community and society more broadly (Shields, 2017).

The approach also aimed to support students to become self-regulated learners. We define self-regulated learners as those who possess independent critical thought and literacy that can challenge Western ways of knowing, where Western ideas of a separated human and nature relationship can privilege other ways of knowing and being (Gammage, 2011; Ross et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2021).

The goal of the learning activity is to create greater understanding of listening to help develop students to become self-regulated learners. According to the literature, “self-regulated learning” has been defined as an “active, constructive process whereby learners set goals for their learning and then attempt to monitor, regulate and control their cognition, motivation, and behaviour, guided and constrained by their goals and the contextual features of the environment” (Pintrich, 2000, p. 453). In self-regulating listening, the listeners set goals for their listening and then apply their knowledge, attitudes and skills as communicators to their listening acts. The problem is that listening goes unrecognised as a key skill or is something that is seen to come “naturally”. Field trips provide a way of engaging the senses and, in particular, engaging in deep listening to help build awareness, skill and then self-regulation. This pedagogy is not just about the physical capacity to listen (and not be distracted), but is also an opportunity to reflect upon different participants’ cultural situatedness. Field trips are instructional settings that have the potential to help participants shift out of their own situatedness. To achieve this, our study has used focus groups and interviews to help field trip participants reflect on their experiences and to listen to the perspectives of others.

Different students listen and absorb different perspectives. This is not a new idea, but we suspect that this generation, which is used to digital devices and blended learning, listens differently to past generations. Developing greater self-awareness of listening habits and being able to set goals for listening can help managers when faced with challenging scenarios in the workforce and community more broadly. They may also possess greater emotional intelligence, and this field trip is a proactive effort to sensitise future managers to become better listeners through a pedagogy of sound. Thus, this research has strong ethical and managerial implications that come from such an experience.

The field trip itself provided students with the opportunity to interact with the human and physical environment and reflect upon their listening competency. Learners were encouraged to take notes during the field trip and develop strategies to develop their listening competency and consider how they might adopt an “acousmatic” attitude. Learners who recognise that each interaction is both empirical and phenomenological may consider ways that their listening provides an “expanding, imaginative sense of space” and “an enlargement of human life” (Arnett, 2019, p. 187)

An additional important aspect of the field trip is the reflections of the academics who accompany these students. We have yet to capture this information; however, it will add considerably to the literature on field trips and Indigenising the curriculum from multiple perspectives once documented.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the UQBS Indigenising the curriculum initiative has begun the journey of integrating, embedding and prioritising Indigenous knowledges and perspectives in our School curriculum. This chapter has discussed some of the initiatives to date and highlighted two examples, both of which were important learning opportunities, not just for the students, but for the teams involved in their development and implementation.

The mix of different approaches outlined – the innovative approach taken in the MBA and MFIM programs, where the curriculum development places Indigenous perspectives and knowledges at the core of the curriculum, and the Grotesque Quest and Deep Listening on Minjerribah – has seen the team engage in iterative development of courses, focusing on gaining buy-in from the academic teams to support the Indigenisation of the courses. In the case of Deep Listening on Minjerribah, this has involved relationship-building and co-designing the initiative with Aboriginal stakeholders and knowledge holders.

These different approaches have set us on a positive path forward in terms of starting the transformation of the curriculum in UQBS. There have been many lessons learned along the way by the Indigenising curriculum team and the academics and learning designers we are working with, and we continue to grow and develop the approaches used.

We continue to look for ways to recognise and highlight Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being and doing in our business programs. Through curriculum and through partnerships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics, and the wider Indigenous community of South East Queensland and beyond, the School aims to prioritise creating meaningful engagement with Indigenous communities and businesses.

Reflection questions

- How do you feel about making mistakes in the process of Indigenising a course or curriculum? What does it mean to be accountable for your mistakes and move forward?

- What can you do to strengthen relationships between non-Indigenous and Indigenous peoples involved in Indigenising courses and curricula? What strengths do you bring to this process? What does reciprocity look like in your context?

- How might you integrate the UQ campus into an Indigenised course or curriculum? How might you help your students understand that UQ is located on Aboriginal land?

- How might you integrate Country into an Indigenised course or curriculum? Is a field trip or guided on Country experience possible? What steps need to be taken to facilitate this, noting that we are “on Country” wherever we are?

- What are some ways you could introduce and apply dadirri to Indigenising curriculum in your own field or discipline?

- Consider how yarning could be applied in a learning context. How does this differ from other methods utilised in teaching and learning to engage students in discussion and reflection?

References

Altman, M., Young, T., & Lamontagne, L. E. M. (2017). Improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander student participation, retention and success in Australian business-related higher education. University of Newcastle.

Arnett, R. (2019). Response: Dialogical listening as attentiveness to place and space. International Journal of Listening, 33(3), 181–187.

Atkinson, J. (2002). Trauma trails, recreating song lines: The transgenerational effects of trauma in Indigenous Australia. Spinifex Press.

Australian Business Deans Council [ABDC]. (2019, May 27). ABDC president: Business schools can do more to attract Indigenous students. https://abdc.edu.au/abdc-president-business-schools-can-do-more-to-attract-indigenous-students

Bessarab, D., & Ng’andu, B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 3(1), 37–50.

Gainsford, A., & Evans, M. (2020). Integrating andragogical philosophy with Indigenous teaching and learning, Management Learning, 52(5), 559–580.

Gammage, B. (2011). The biggest estate on earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin.

Gershon, W., & Appelbaum, P. (2018). Resounding education: Sonic instigations, reverberating foundations. Educational Studies, 54(4), 357–366.

Go-Sam, C., Greenop, K., Marnane, K., & Bower, T. (2021). Campuses on Countries: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander design framework at The University of Queensland. The University of Queensland. https://doi.org/10.14264/955791e

Hartwig, L., Jackson, S., Markham, F., & Osborne, N. (2021). Water colonialism and Indigenous water justice in south-eastern Australia. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 30(1), 30–63.

Harward-Nalder, G., & Grenfell, M. (2011). Learning from the Quandamooka. Proceedings of The Royal Society of Queensland, 117, 495–501.

Ihde, D. (2012). The auditory dimension. In J. Sterne (Ed.), The sound studies reader (pp. 23–28). Routledge.

Kwaymullina, A., Kwaymullina, B., & Butterly, L. (2013). Living texts: A perspective on published sources, Indigenous research methodologies and Indigenous worldviews. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 6(1), 1–13.

Maguire, A., & Young, T. (2017). Indigenising of curricula: Current teaching practices in law. Legal Education Review, 25(1), 95–119.

Marketing and Communication. (2021). Carving a history: A guide to the Great Court, The University of Queensland St Lucia. The University of Queensland. https://marketing-communication.uq.edu.au/carving-a-history

Marnane, K., & Bower, T. (2021). Campuses on Countries: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander design framework engagement report at The University of Queensland. The University of Queensland. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:c684e38/UQ-Engagement-Report.pdf

Martin, K. / Mirraboopa, B. (2003). Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and Indigenist re-search. Journal of Australian Studies, 27(76), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050309387838

Orion, N., & Hofstein, A. (1994). Factors that influence learning during a scientific field trip in a natural environment. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 31(10), 1097–1119.

Osborne, N. (2015). Stories of Stradbroke: Emotional geographies of an island in transition [Unpublished PhD thesis]. Griffith University.

Page, S. (2014). Exploring new conceptualisations of old problems: Researching and reorienting teaching in Indigenous studies to transform student learning. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 43(1), 21–30.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 451–502). Elsevier Academic Press.

Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation [QYAC]. (n.d.). Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation. http://www.qyac.net.au/

Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation [QYAC]. (2018). Native title. http://www.qyac.net.au/NativeTitle.html

Ross, A., Pickering, K., Snodgrass, J., Delcore, H., & Sherman, R. (2011). Indigenous peoples and the collaborative stewardship of nature: Knowledge binds and institutional conflicts. Routledge.

Shields, C. (2017). Transformative leadership in education: Equitable and socially just change in an uncertain and complex world. Routledge.

Ungunmerr-Baumann, M. R. (2002). Against racism. Compass, 37(3).

Ungunmerr-Baumann, M.-R., Groom, R. A., Schuberg, E. L., Atkinson, J., Atkinson, C., Wallace, R., & Morris, G. (2022). Dadirri: An Indigenous place-based research methodology. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 18(1), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/11771801221085353

University of Queensland, The. (n.d.). Toward 2032: UQ strategic plan 2022–2025. https://about-us.uq.edu.au/strategic-plan/toward-2032

Walker, M., Fredericks, B., Mills, K., & Anderson, D. (2013). “Yarning” as a method for community-based health research with Indigenous women: The Indigenous women’s wellness research program. Health Care for Women International, 35(10), 1216–1226. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2013.815754

Yan, L., Litts, B., Colleni, M., Isaacs, D., & Tehee, M. (2021). (Re)presenting nature: Sixth graders’ place-based field trip experience through restorying. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS) 2021, Bochum, Germany, 693–696.