1 Storying in architecture design studio

Mirndiyan Gununa Art Centre

Carroll Go-Sam and Kelly Greenop

School of Architecture, Design and Planning

Introduction

In many ways we are among the most fortunate disciplines at The University of Queensland (UQ) because of our role in the development of what is now called First Nations architecture into a distinct category of architecture, a field of research and practice, and a movement within our profession. The School of Architecture, Design and Planning (ADP), its academics, PhD students, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander collaborators and others across Australia were instrumental in instigating and fostering the work that led to the acceptance of First Nations architecture as an academic category and a professional practice. What began in the 1970s as the Aboriginal Data Archive, and through the early work of our colleagues and later our own, evolved into the Aboriginal Environments Centre, which has been active for decades, and is now part of the School’s Architecture Theory Culture History (ATCH) research centre. Professor Paul Memmott and Dr Cathy Keys wrote a history of this centre in 2016. Members of our School, both staff and adjuncts, have also influenced the changing inclusion of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in our profession, as part of the (then) First Nations Advisory Working Group in the Australian Institute of Architects, which achieved a change in the professional competencies for architects to mandate knowledge and skills in working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and understanding Country for graduating architecture students. The official change occurred in 2021, and our staff, graduates and adjuncts are among a handful of people across Australia who now assess the inclusion of these performance criteria within professional architecture degrees nationally. Typically, these same people have included in their teaching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander academic and non-academic content, community links including site visits, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander guest lecturers, reviewers and experts, and design briefs set in Indigenous communities, Indigenous organisations or institutional settings.

Yet, like many other parts of UQ Indigenising the curriculum, ADP still has challenges. What is often seen as specialist knowledge has typically been included within small, elective courses where students can opt-in to the content, rather than being embedded within larger compulsory courses taken by the whole year cohort. Colleagues who are unfamiliar with First Nations architecture can be hesitant to change their courses to include content that they are less familiar with and are particularly nervous about “getting it wrong” and causing offence or being called out as ignorant or inappropriate (Memmott & Keys, 2016). A common quick-fix solution has been to include a single guest lecture incorporating Indigenous themes in architecture. Generally, guest lectures are not integrated into assessment items, so subsequent deeper study and learning does not occur. In a major change to architectural pedagogy across Australia, the 2021 National Standard of Competency for Architects (NSCA) accreditation has First Nations content inherent to seven of the 43 professional performance criteria (Architects Accreditation Council of Australia, 2021) that our graduates in the Master of Architecture – and consequently our courses – must demonstrate. We have, therefore, moved into a new era of larger core courses that must embed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge, engagement and understanding of Country into the curriculum. A new challenge for our School, and all architecture schools across Australia.

This chapter will discuss shared studio coordination of an undergraduate architecture course by Carroll Go-Sam, Dyirbal gambilbara bama of Ravenshoe, North Queensland, one of Australia’s leading First Nations architecture academics,[1] and Associate Professor Kelly Greenop, a graduate of the School who has worked with Carroll, Paul Memmott, Cathy Keys, Tim O’Rourke and others within the School for many years. Both Carroll and Kelly teach and undertake research projects in the School, co-advise PhD students and collaborate with colleagues externally. We will outline here the work to develop a new third-year Bachelor of Architectural Design course, using storying as defined by Louise G. Phillips and Tracey Bunda’s Research Through, With and As Storying (Phillips & Bunda, 2018) alongside embedding values of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander collaboration, engagement, developing understanding of Country as a regional system of knowledge and, more broadly, intercultural design for a client with a global and national reputation.

UQ School of Architecture, Design and Planning context

ADP has multiple undergraduate, master’s and postgraduate degree offerings. Bachelor’s degrees in Architectural Design (BArchDes), Regional and Town Planning (BRTP), Design (BDes) are completed in three years full-time/six years part-time equivalent. Dual bachelor’s degrees with honours offerings include Business Management/Design (BBusMan/BDes Hons), Engineering/Design (BEng/BDes Hons) and Information Technology/Design (BInfTech/BDes Hons). Master’s programs are second-stage degrees leading to professionally accredited courses in Architecture (MArch), Urban and Regional Planning (MURP), and Urban Development and Design (MUDevDes). Higher Degree by Research programs include Doctor of Philosophy and Master of Philosophy. Students studying for a bachelor’s degree can choose several elective courses within architecture and other disciplines. Compulsory architectural design studios, technology, architectural business/practice management and humanities courses are completed each year, with one architectural design studio undertaken each semester. Two design studios are undertaken each year of the three-year undergraduate degree course, hence a total of six architectural design studios are completed. The third and final year of the bachelor’s degree is referred to as the final year. The Master of Architecture is a two year full-time and four year part-time equivalent program. The last year of the program coursework is confusingly also called final year, but is distinguished colloquially as the final year of the master’s program.

The course we developed was offered in the first semester of year three of the undergraduate architecture design studio program. It has a double load (4 units) and has a full day of learning timetabled each week. This course is typical of the design studio type in our undergraduate degree, in which students are asked to act as the designer of a project, and they develop their skills and knowledge within the context of this project set by the teaching staff. Each studio has a design brief that sets out the project they must undertake and gives students particular constraints and prompts to develop specific architectural design and other skills that sit alongside design, such as technical, social or cultural knowledge or methodology. The course we developed is ARCH3100 Architectural Design: Clients and Culture, for third-year Bachelor of Architectural Design students. It is a compulsory core course, typically taken by the whole cohort, and, in addition to design skills, students address the need to learn and apply cross-cultural skills to a design solution. We asked students to complete designs in response to the ARCH3100 brief, which we called A New Art Centre for Mornington Island Mirndiyan Gununa Art Centre. The studio had a total of three iterations between 2022 and 2024. While this three-year cycle is not a fixed general rule, teaching assignments and strategic adjustments often lead to course renewals after a similar duration. In the case of ARCH3100, both Carroll and Kelly moved to new courses after three years, and the course has another staff member returning to teach this course once more, also pursuing an Indigenised approach as we discuss below.

There have been previous clients and culture studio iterations reflecting and incorporating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander issues prior to the Mirndiyan Gununa Art Centre studio detailed below. For example, Dr Tim O’Rourke had previously coordinated and taught into ARCH3100 for five years and worked with the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health (IUIH) and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Health Service (ATSICHS) to provide students with a real-life scenario of designing a community-controlled health clinic and social services aligned with urban Indigenous community health models of care. He has returned to teach this course in 2025, again working with IUIH, demonstrating the fortunate depth we have in teaching a variety of embedded First Nations studios in our courses.

The stated aim of the ARCH3100 course is to “extend students’ capacity to respond to the opportunities and constraints presented by diverse clients and cultural contexts” (see course profile, UQ, n.d.). The learning objectives state that by the end of the course students should be able to:

- Analyse the opportunities and constraints presented by cultural diversity in relation to a given architectural problem.

- Apply client and user responsive design strategies to a complex design problem.

- Communicate a developed design proposal using communication techniques appropriate for diverse audiences. (see course profile, UQ, n.d., emphasis added)

Thus, both the activities of the students – to understand and respond to their client’s cultural needs – and the way they communicate their design – appropriate for diverse audiences – embed broader imperatives to incorporate Indigenising the curriculum meeting the professions requirements, and UQ’s Indigenising the curriculum objectives. Further, we are wanting to scaffold our students’ learning in their undergraduate courses, which will be more rigorously developed and tested at master’s program level, when the NSCA graduate performance criteria are assessed, as discussed above.

Our positioning

Carroll: My people are Dyirbal gambilbara bama. Gambilbara Country originates from two words “gambil” meaning “rocky high country” and “bara” translated as “place”. Gambilbara refers to one of the two-part composite of Dyirbal Country, peoples and social organisation. The other is yabulumbara, with “yabulum” meaning “lower country grassy plains”. The word “bama” equates to a person from the rainforest region. My surname Go-Sam is from the 19th century. It is a transliteration of the Chinese name Gow San. I also have Chinese ancestry and, separately, family connections to Yugambeh and Jagera/Yuggera in South East Queensland. I strongly identify with my lived experiences, shared oral histories, and towns and places within Dyribal Country – too many places to mention, but mainly Ravenshoe, Herberton, Atherton, Silver Valley and Innisfail. I grew up in my uncle’s Country, Yidinji mullenbarra (Gordonvale) and Gimuy yidinji (Cairns). I’ve resided and worked in Jagera-Turrbal Country for several decades. Kelly and I have worked together for a long time. We both began as junior tutors over two decades ago, teaching into Aboriginal Environments courses, and have collaborated on numerous projects, consultations, teaching and research grants.

Kelly: I am a settler Australian, of Scottish, English and Irish heritage, living and working in Brisbane, often also called Meanjin. I grew up in Lismore, on Bunjalung Country, and was fortunate to go to school with many Aboriginal kids in Lismore, and to study here at UQ with some of Australia’s earliest Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander architectural graduates, such as Carroll and Andrew Lane. I feel deeply connected to the northern rivers of New South Wales and the coastal areas of Byron Bay and Lennox Head, the place of many childhood and adult memories with family and friends. Living on Jagera-Turrbal Country in the same neighbourhood for more than 30 years, I am also very attached to this place and enjoy and try to support its plants, animals, seasons, soils and waterways. I am also very attached to and grateful for my UQ architecture and wider network of colleagues, students and alumni, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community collaborators who have helped shape my understanding of First Nations architecture across decades.

Indigenising the tertiary architectural curriculum, and the profession

The Indigenising of curriculum in our degrees has been occurring on a course-by-course basis, driven by the dual motivations of the ethical imperative strongly embedded within our teaching staff and the shared research agenda which foregrounds First Nations architecture, built environments and social justice outcomes in communities. The recently refreshed UQ graduate attributes (UQ, 2024) also encompass many elements that align with Indigenising the curriculum, namely, that our graduates are accomplished scholars, courageous thinkers, connected citizens, culturally capable, influential communicators and respectful leaders. Being “culturally capable” means that:

Graduates will have an understanding of, and respect for, Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and global Indigenous peoples’ values, cultures and knowledge. They will have an appreciation of cultural and social diversity and work with a sense of social and civic responsibility towards a more just and equitable society. (UQ, 2024, item 13 d.)

This provides a strong university-level motivating factor that sits alongside the professional capabilities embedded within the NSCA requirements we have already flagged. Indigenising our curriculum is now beyond a “nice to have” and has become a professional imperative.

We will highlight the links to these structural requirements as we explain our course content and teaching approach in the following section.

Engaging with a new but growing Indigenous architecture scholarship

To position our work and the knowledge that we want students to start grappling with, we first turn to literature and the history of writing about First Nations places, building and ways of living. While many people are not familiar with the content and depth of this scholarship, its current niche status does not reflect a complete lack of content, and, while still developing, provides a strong starting point for students. Globally there have been a small number of dedicated, well-informed non-Indigenous academics, architects and contributors developing scholarly literature and theories on Indigenous architectural perspectives. These contributions have critically shifted and dissected postcolonial perspectives in architecture. Some of these methodically mapped dominant paradigms in Western architecture and questioned its values, policies, methods, operations and identities (Hosagrahar, 2012). We have incorporated these and other available literature from architecture professional journals or online content, but many of these resources lacked information on Indigenous knowledge holders’ contributions to project outcomes in any depth or detail.

A corrective element of our curriculum development work has involved repositioning First Nations contributions from subservient to the nation-state’s aspirations of national reconciliation and cultural tourism, and elevating willing participation to include social objectives and political perspectives initiated by Indigenous organisations, community representatives and advocates. We engaged students in questioning representations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culturea that were deficit-based or romanticised. A key to this is to simply present Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with diverse histories, politics, opinions and perspectives.

The use of written academic texts to support First Nations architecture curriculum is a challenge, because of the relative newness of the field within academic discourse. But this challenge is one in which creative thinking and delving into First Nations-led work has enabled us to both provide appropriate sources and teach students ways in which to judge literature and other media sources for their appropriateness. Admittedly, the time constraints of the studio do not allow in depth critical examination of essentialism and cultural hierarchies. Our approach links to developing students as both accomplished scholars and culturally capable. Until relatively recently, few architectural publications in Australia had been authored or co-authored by Indigenous writers, designers or architects. For the ARCH3100 course, content was carefully drawn from a selection of allies and First Nations architects, authors and academics in Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, First Nations Canada, the USA and Pacific nations. These resources offered insightful analyses about influences, intentions, conditions and changes over time of First Nations peoples’ goals and practices (Heynen & Wright, 2012).

The provision of non-academic material is imperative when understanding a First Nations community. In this respect, the internet has afforded greater access to diverse materials, including on First Nations perspectives, but often without disclosing the origins of the content, its basis in First Nations society or relevant cultural permissions. We have found that students need to equally understand the cultural, political and economic contexts of available materials to be able to properly interpret and deploy them. This enables us to teach how to judge these sources, check their origin and understand what can be learned from each type of source. Students are often uninformed about postcolonial power dynamics and need to better understand mainstream media and positioning of First Nations peoples, communities, projects and news items. Additionally, they needed to learn about “new” (for many of our students) content sources that showcase diverse Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives (such as NITV, Indigenous X or Koori Mail), and their history, reliability and position within heterogeneous First Nations societies. It is important that students learn, in encountering these sources, the deficits of the academy, alongside the challenges faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders communities. These two issues are often related and require ways to think about how to account for these deficits.

Tip

Tip

For novices engaged in Indigenising curriculum, ensure you start from a position of curiosity yourself, as a co-learner. Start with one or two new items and build content over time.

Tip

Tip

Incorporated content should be included in class discussions and, where feasible, assessable. Write prompt questions, and/or direct students to reflect and do deeper research beyond the learning resources provided.

Equally essential for students was contextualising Indigenous rights, dignity and protections through the provision of guides (external sources) and guidance (in class) on cultural respect, safety, Indigenous cultural and intellectual property rights (ICIP), and warnings against cultural appropriation. This is a key element toward becoming a culturally capable graduate. It is also encompassed specifically in the NSCA required within the Master of Architecture degree that we want our students to be primed for.[2] Prior to the ARCH3100 course, Indigenising the curriculum in our discipline was conducted across different courses offered in our School, and included diverse multimedia content on Indigenous Country, histories, places and architecture in both design and research courses. Staff juggled a mixture of teaching and research budgets to include invited Indigenous guests with a variety of voices and disciplines, such as architects, designers and other disciplinary professionals, academics, and knowledge holders from diverse locations. They spoke about both community and architecturally related topics. However, as outlined earlier, many of these courses were electives across our undergraduate and master’s degrees, few were core courses that embedded this learning into the program for every graduate.

Studio based in a real community with real needs

The development of the ARCH3100 studio program described here began as a research project with our collaborator, then at UQ, Dr Kali Marnane. Kali had a chance encounter at the airport in Gununa on Mornington Island in Queensland’s Gulf of Carpentaria while visiting family working in the community, and was invited by a member of the community to contribute to their development of housing plans. While this request grew into a separate research project that analysed the current community housing adequacy and documented the community’s housing design needs (Go-Sam et al., 2024), we also saw an opportunity to link to the undergraduate curriculum.

Carroll and Kelly were tasked to collaboratively teach the ARCH3100 Architectural Design: Clients and Culture design studio course which aims to provide an “introduction to cross-cultural design … [and] develops skills in understanding the implications of social and cultural preferences on architectural design” (see course profile, UQ, n.d.). To achieve this, students are tasked to develop an architectural design project that “accurately registers the culture and needs of existing and /or potential users … in the respectful apprehension of cultural and physical diversity” (see course profile, UQ, n.d.). Thus, First Nations communities provide a possible, but not mandated cultural group, which could be used as the basis for these learning goals. In this instance, we developed a project design brief that demanded centring First Nations worldviews, perspectives and knowledge in the studio program. We hoped the studio could contribute design ideas back to the Gununa community through student work and also give students a challenging design proposition at the intersection of First Nations culture, place and architecture.

The separate housing research project took us, Carroll, Kelly, Kali and other colleagues, on several trips to Gununa on Mornington Island in late 2021 and through 2022. During this project we worked with the community, the Mornington Island Shire Council, Mornington Island State School and other organisations. One of the most welcoming and connected places we encountered was the Mirndiyan Gununa Art Centre. It was run by manager John Armstrong, a non-Indigenous man respected by the community, and assistant manager Bereline Loogatha, a local woman from the Kaiadilt people of nearby Bentinck Island. When on the island, we gathered at the art centre, where world-famous Mornington Island women painters have been based, such as the late Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori, and many other Lardil, Kaiadilt, Gangalidda and Yankaal families of artists. The art centre was a place for meeting with the community, hanging out, having cups of tea, browsing and buying artworks, and patting dogs. We waited at the art centre for our plane from Cairns to arrive, as it is conveniently located right next to the small airport. Not only did we as visitors, but many community members gathered at this art centre. In addition to the active artists group and their families, especially grandchildren, and school children learning language and culture, there were other informal congregations. Despite the building’s importance, being loved and well-used, it is aging, has had multiple layers of alterations, repairs and adaptations, and is in need of renewal.

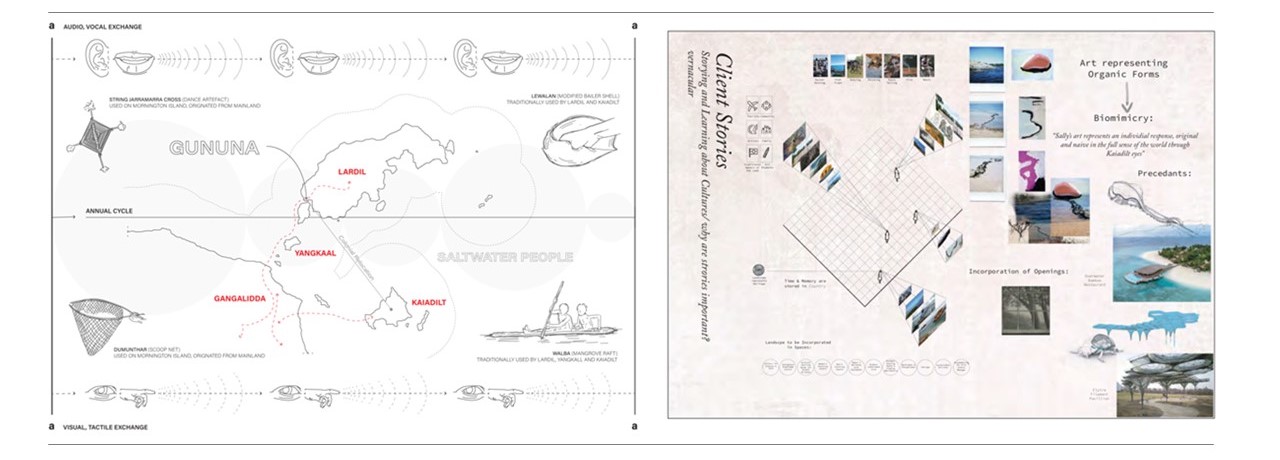

Given the significance of the art centre to Gununa social and economic life, and the inadequate nature of the current facilities, we devised a student project to design a new Mirndiyan Gununa Art Centre. This would offer an opportunity to expand the women’s artist studios, and include men who do not currently have dedicated space at the art centre. The students’ design brief we devised in conjunction with John and Bereline incorporated a gallery, a dance-performance area, manager’s residence, cultural artefact keeping place, an educational space to cater for children who already visit the art centre for language learning, and improved storage and support spaces. The new art centre also needed to provide emergency accommodation in case of severe cyclonic weather – accommodation that is in short supply in Gununa. This provided both of the client groups – the art centre managers and the Gununa community at large – the cultural setting for multiple Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups that comprise the place.

The students’ studio task could not be successfully completed by defaulting to Western social and cultural normative assumptions based on prior knowledge. Each year’s cohort of students had limited to negligible understanding of First Nations architecture, social cultures, languages, places, histories and knowledge, though in at least one year there was a First Nations student in the cohort. International students have additional challenges of English language fluency and cross-cultural comprehension. Unlike most of our design studios, students were unable to undertake in-person site visits due to the logistics of distance, cost of travel and lack of visitor accommodation available on the island. All these factors limited access to Mornington Island and student face-to-face meetings with the Gununa arts community. This did not present a barrier to gaining a comprehension of client and artist design needs, but it did place an obstacle to experiencing the physicality of the place, built environment, and social and economic settings.

Tip

Tip

To build relationships with Indigenous people, communities or organisations don’t start from a place of how these can assist you in your course or teaching; rather, recentre your approach and ask what can my profession or my students’ skills offer the community organisation to enhance/support/advance their aspirations.

Each year we provided five of the best students’ works back to the community to show the outcomes of the project. While we offered to provide student presentations and other supporting material, at the time it was not a priority for the Mirndiyan Gununa community to hear from the students about their work. In an ideal world, where funding was plentiful, we had hoped that students’ work could at least contribute towards ideas for an expanded art centre, but, amidst many other pressing community issues to deal with, this one was not prioritised for discussion by the art centre managers or artists. Explaining to students the concepts of “cultural load” and “cultural safety”[3] was an especially important factor in centring Gununa people’s experiences and needs first, rather than outsiders’ needs (in this case ours, as students and educators). The broader research project about Gununa housing did proceed and was completed and reported back to the Mornington Island Shire Council and utilised to inform government programs. An important perspective about who a community design project is serving is given by Go-Sam, Philips and Gilbert in their forthcoming paper about Indigenising architectural education (Go-Sam et al., 2025).

Architecture studio pedagogy and learning resources

Architecture studio pedagogy enables learning and development of design skills. The 13-week program addressed a complex design brief with learning supported by weekly lectures and hands-on set studio tasks. Studio encourages collaborative work, critical thinking and reflection through both formal and informal learning. Work is undertaken weekly within the studio day (typically six hours), and occurs in tutorial groups and individual feedback sessions with the tutor and is supplemented by additional individual design work pursued outside of the studio time. Students engage in a mixture of desktop research, iterative design problem solving and critical examination of architectural precedents. Students’ work is assessed across three submissions consisting of architectural drawings, 3D physical or digital models visually communicating key parameters of the project in the form of concept ideas and resolved schematic design. Minor assessments are visually and orally presented before an assembled panel of teaching staff, tutors and peers. For the major assessment piece, visiting industry architectural practitioners, allied professionals and invited academics are formed into critique panels that hear from students about their projects, then question and comment on the work. This is standard across the architecture discipline in our School, and common to many other institutions.

The Mirndiyan Gununa teaching studio invited cross-cultural competency awareness through achieving a basic understanding of First Nations people’s histories, spatial preferences, lifeways and perspectives. Students were also required to resolve technical and functional programs of buildings, and design with an informed awareness of the constraints, including the impacts of remoteness on construction supply chains, skilled labour scarcity and interruptions caused by seasonal tropical cyclonic weather influence design choices. Lecture topics addressed the specific properties of place and culture, technical parameters of climate design, exemplary design precedents and planning strategies from First Nations perspectives. Multimedia learning resources released weekly broke down set tasks assisting student comprehension to better understand the complex brief and operations of the art centre.

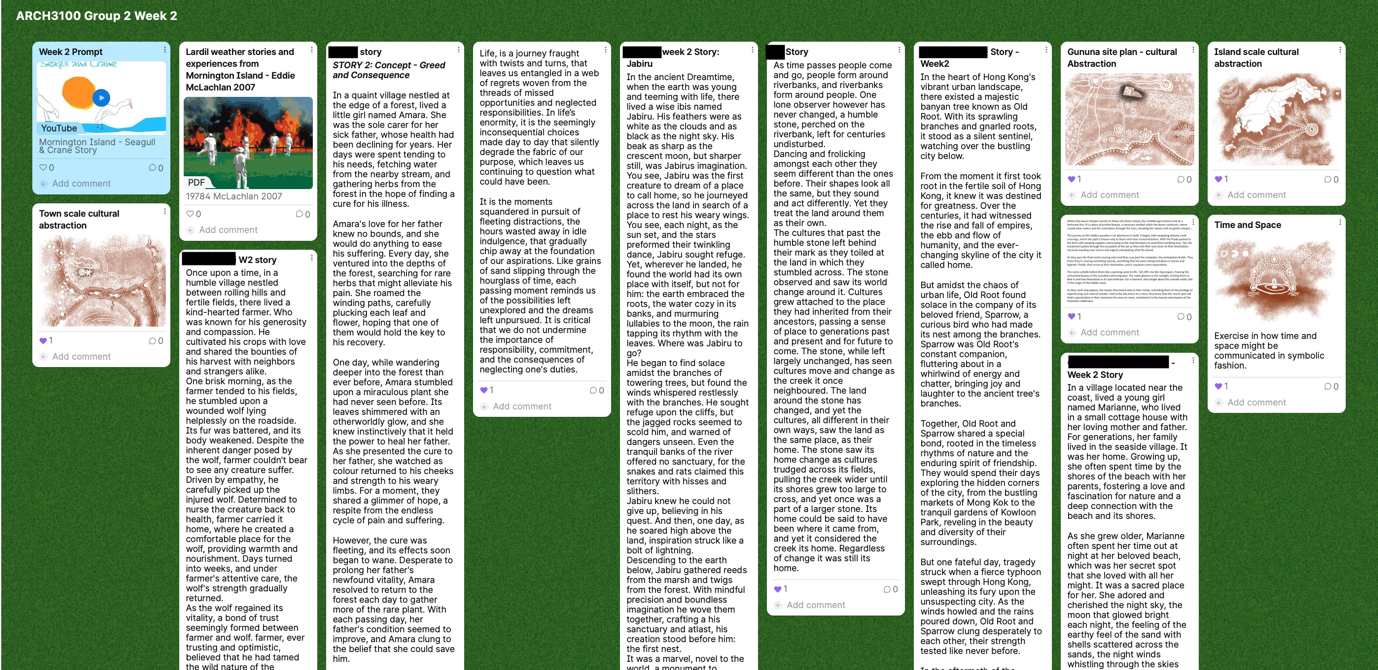

Incorporating storying to unlock students’ empathy

The ARCH3100 approach for the first two years involved providing a culturally driven and diverse set of learning resources covering contemporary First Nations cultural and arts practices, colonial conflict, concepts of Country, island dynamics, and regional histories as told by First Nations knowledge holders and non-Indigenous authors. Written and video accounts provided critical insights as told from unique perspectives of Kaiadilt, Lardil, Gangilidda and Yankaal peoples recalling visits, removal, separation, longing, sadness, and happiness and celebration on and off Country. There were stories about experiences of mission life and language group dynamics. Other content impacting on design responses and decisions included social protocols (age, gender, and avoidance relations, e.g., mother-in-law and son-in-law), Lardil climate and seasonal calendar, streetscape videos of Gununa streets, photographs of key places and Mirndiyan Gununa site context. Many of the First Nations resources shared had existed for several years and were co-developed through Indigenous-led community organisations. Importantly, the content was narrated by knowledge holders, in their own voices, relaying public stories others were permitted to hear.

Tip

Tip

Resources on getting started with Indigenising the curriculum in architecture programs can be found through the Australian Institute of Architects’ First Nations Resources Hub (n.d.), Parlour’s Deadly Djurumin Yarns (2023) and the Architects Accreditation Council of Australia’s First Nations Performance Criteria material (n.d.). These are just a starting point, and there is a lot of material out there to explore.

As course coordinators, our role is to contextualise learning content, emphasising the dynamic nature of place and culture. The Mirndiyan Gununa Art Centre provided a YouTube video (11:56 mins) walk-through of the existing Mirndiyan gallery shop and studio. It featured key staff and some artists. The art centre website provided personalised artist profiles, photos of artists, and links to public-accessible traditional stories narrated and illustrated by Gununa storytellers. We were gifted exhibition catalogues and also purchased arts publications featuring artists. The Lardil people’s Country includes Mornington Island, yet artists are representative of larger family groups from diverse Countries in the region, from mainland Gangalidda Gulf communities of Burketown and Doomadgee, and including Yangkaal and Kaiadilt Countries in the Wellesley Island archipelago, so the material we included sought to convey varied perspectives.

The studio required students to embark on a steep learning curve to become familiar with place and social histories, operations of the art centre, and artist studio activities. In the first two years of the studio, many students grappled with understanding the complex brief and the cultural setting. Some students arrived at a good comprehension of the spatial and social features of the brief, its key functions and dynamics of place. Others achieved partial understanding, focusing on the technical resolution of the design, yet others struggled, only attaining superficial outcomes.

Prior to the last year (2024) in which the Mirndiyan Gununa Art Centre project was offered, we reflected as studio coordinators on how students could arrive at designs more integrated with Gununa as a place, its people and cultures. We sensed among some of the design results students achieved to that point, and from some students’ comments, that they were not feeling connected to the clients or the culture. The responses they were making in their design ignored community setting, and hence a new approach was needed. In yarning about this extensively, Carroll and Kelly decided that we needed to disrupt default design practices and methods of knowing and learning cross-cultural concepts. We discussed how an increase in empathy for the clients and the lived experiences within the Gununa community was needed. We wanted to unlock that, to free up the empathic creativity of the students. At a 2023 UQ Teaching and Learning Week presentation by Tracey Bunda, Katelyn Barney and Nisa Richy, we heard about their teaching and learning project with their colleagues Lisa Oliver, r e a Saunders and Stephanie Gilbert to work with students to “weave” a “knowledge basket” through storying (Bunda et al., 2024). This was the catalyst we had been needing, and we immediately inhaled the information on storying and decided to adapt and apply it to the next iteration of the studio.

We used storying as a different way of communicating design, place, remoteness, and the needs and values of community/artist family groups. This was both essential to the official course learning objectives and to becoming a sensitive and culturally capable designer. Storying was introduced as both a learning process and adventure in mutual learning between us as teachers and themselves as students. It was differentiated to yarning, a two-way cultural conversation, as outlined in Bronwyn Fredericks and colleagues (Fredericks et al., 2011). The approach emphasised that, if designed well, storying involved more than an intellectual exercise or a set of applied techniques, and additionally invoked extended reflection and emotional engagement leading to deeper learning. It required openness to changing one’s thinking by developing empathy for the commonalities and differences among all people.

On day one of the 2024 ARCH3100 studio, the concept of storying was presented to students as a way of understanding other people and their own experiences and knowledge as designers by reflecting on two kinds of knowledge: cultural/emotional and factual. To demonstrate storying and model the level of engagement and diverse storying modes possible, both Carroll and Kelly told a story involving themselves in the first week lecture and explained how storying would operate across the tutorials. This emphasised not only an emotional response, but one that valued the lived reality of people in their chosen place of residency. As per previous iterations, researching and analysing facts about Gununa were also included in the tasks for each week’s studio session, such as numbers of people on the island, existing town conditions, and physical requirements for the brief and servicing. The tropical seasonal weather conditions, climate-related cyclic systems, landscape, plants, animals, tides and so on were also included.

The storying was undertaken each week for four weeks, on a tutorial group Padlet (collaborative digital platform) set for each of the four tutorial groups. On each Padlet weekly page we provided a story prompt, and students were invited to respond to specific media, either an audio or video narrative by a First Nations person, or a written piece. It was essential that this was First Nations content so that the cultural and emotional bridge between the non-Indigenous student cohort and the First Nations client group could be built. We were able to find media prompts, text and other content, all emanating from Gununa, ranging from news stories from NITV, to Mirndiyan Gununa Art Centre-produced children’s Dreaming stories as animated videos. On the Padlet, students then responded with their own story relating to what they had seen from Gununa and how it was interpreted by them as new, or connectable knowledge. They could produce written texts, drawings, photographs or other media. When students presented their work in tutorials, they were asked to read their response to storying prompts, before launching into fact-based knowledge.

Cultural safety advice that sat alongside the instructions for the storying task noted that it was not a requirement for students to reveal aspects of themselves they preferred to keep private or that made them feel uncomfortable or vulnerable, especially as we expected some students might have an emotional response to the content. They were encouraged to engage honestly, drawing on their own cultural experiences, in writing about what they were learning or experiencing in the course or their design work.

Finally, in the spirit of mutual respect, they were to treat each other’s stories with kindness, ensuring their stories were free from themes offensive to others. On each group’s Padlet, their weekly stories for the first four weeks accumulated and we, as course coordinators, tried to read and respond to as many students’ stories as possible. Many students commented encouragingly and with curiosity about their peers’ experiences. The first assessment task required students to orally present their work, led by storying.

Tip

Tip

Provide specific guidance to students on how to conduct respectful enquiry in class to ensure cultural safety, while enabling people to ask genuine questions when they lack information. Give guidance in the course materials on ways and times to ask questions, and how to ensure students are being kind to their peers while doing so. Encourage curiosity and a lifelong learning attitude. Provide details of how to access support for students who might feel confronted by difficult histories, contemporary events and topics raised in class.

We anticipated and hoped students might arrive at a more informed comprehension of the new art centre brief. Our aim being to have their projects more strongly woven into the existing community fabric, with a heightened empathic awareness of the artists and their place within the social and economic world of Mirndiyan studios.

Results from the storying: Teachers and tutors all need to engage

Indigenising architectural curricula invites students to gain an informed understanding of an unfamiliar culture and history, people and place knowledge, and learning content. The Mirndiyan studio’s complementary requirement for tutors to encourage student storying about intimate and distant worlds resulted in a spectrum of positive and negative reactions. We acknowledge that it takes considerable and persistent effort for tutors to extend their own learning beyond common architectural and cultural references. It required they confront their own misconceptions to help students arrive at a design proposition for a remote community of Indigenous art practitioners that they were also not familiar with. This is not an easy task but, given the changing measure of professional competency as we have described above, we saw this as an opportunity for their professional development as architects and educators, as well as being part of the requirements of tutoring into the course.

In the 2024 studio, we encountered both tutors and students who had no prior understanding of context or firsthand experiences with heterogeneous Indigenous people. The studio was arranged into four tutorial groups, and three of these four groups engaged with storying fully, posting to the Padlet a combination of storying and drawing, in an open-minded and open-hearted way. Students in one group struggled under the guidance of a tutor who found the concept of storying alien and out of their own architectural-teaching comfort zone. This tutor instead relied on familiar architectural methods and processes in the tutorials, which side-lined the storying method. The other three tutors concertedly expanded their own knowledge of First Nations peoples incorporating the storying method. They embraced it with real enthusiasm and created genuinely safe spaces for mutual enquiry, and learning alongside, which many students commented was revelatory.[4]

Nevertheless, the incorporation of storying into learning as a process was not an unequivocal success. Across the student cohort, there was a tendency to take the path of least resistance, defaulting to informal prior knowledge about Indigenous peoples, rather than undertaking the discipline of formal learning through provided resources and set tasks, including genuine storying. Students who drew on their own incomplete and untested informal opinions resorted to tropes of Indigeneity, organic-shaped plan forms, isolating exotic aspects of culture or Country, stereotypes, or Aboriginal flag iconography as design inspiration and planning devices.

We did not provide cultural competency training to tutors engaged in this course, in part because of structural issues such as employment uncertainty, until a very late stage prior to semester commencing and also due to a lack of funding. We had selected tutors who we knew had prior knowledge of First Nations designs and a respect for this topic, but this did not extend to an awareness of storying, let alone training in it, which was also new to us as course coordinators. A deeper preparation that includes cultural competency training and workshopping any new methods, such as storying, would be likely to lead to better results.

Tip

Tip

The assumption that Indigenising the curriculum can occur without additional resource support is not realistic. Investment in training and education for staff at all levels and providing time for them to become familiar with new materials and methods is needed.

A variety of engagement and comfort levels

Despite the variation in skill and engagement across tutors, most students engaged in the studio with a persistent commitment, and many commented that they found the storying method useful to help them relate more to the studio content. The positioning of the project’s clients as fully formed people with histories, cultures and families, which were not identical but also not totally disconnected from their own experiences of places, families and culture, was overall well received. Most students posted storying instalments that incorporated their background, identity and life history. Some students experienced social emancipation from the typical strictures of the student architectural designer to openly share family stories, resulting in meaningful learning engagement and an increased sense of belonging within the course. We found that for some international students, in particular, themes of cultural difference, family structures and the importance of traditions were highly relatable, and they were pleased to share more about themselves with their class colleagues. Others responded with a heightened sense of social responsibility and carefulness about generating design concepts that had a tight social and economic congruence, a response based on empathetic engagement with the conditions within Gununa. A few students experienced an ethical disruption, questioning their own validity to occupy land belonging to First Nations peoples.

In contrast, a few students found it difficult to shift their focus away from their own readily arrived at conclusions about the Gununa community and artists. A minority engaged with negative online content around Aboriginal peoples and cultures, which is unfortunately prevalent in some online algorithms. Several students only passively engaged with the formal learning content. They responded to the brief without any notable knowledge shift, beyond superficial references to the Gununa arts community and its physical place setting. A minority viscerally resisted storying and one student made a formal complaint about the use of what they described as an “experimental storying method” and their experience of “unsupported learning”. We responded to this complaint with radical levels of care and engagement with that student and others who were struggling with storying, modelling the open-hearted and empathetic approach that we advocated for them to adopt into their learning about others. While the student most affected still found the content and storying approach a challenge, expressing their preference, tellingly, for doing things “the normal way”, they did improve their learning approach and, interestingly, seemed to be less stressed by the process as the semester proceeded.

Tip

Tip

Instilling a culture of lifelong learning in your classroom can help students to understand that, beyond their immediate concern for achievement and marks, a bigger goal of learning to keep learning is worth pursuing. We found that caring for the whole student, despite any resistant immediate responses they might have had, helped show that we were “on board for the journey” through what might be for them difficult new learning.

Next steps and new challenges

We will continue creating briefs centred on diverse First Nations communities, with the realisation that new cultural concepts, analyses and place values cause unknown and uncomfortable responses. We seek to invite curiosity, knowing we will encounter reluctance and even resistance and, occasionally, criticism.

Carroll and Kelly completed our series of ARCH3100 following the above storying-inclusive version at the end of 2024. Carroll is stepping back from teaching to undertake a Higher Degree by Research commencing in 2025. The challenge we now face, along with our colleagues, is to transfer the learning from this course and others pursuing an Indigenising path into other courses, both in terms of student and teaching experiences. Crucially for our discipline, we need to ensure that learning of this type, and of a higher order suitable for the Master of Architecture curriculum, is carefully designed into new iterations of courses. We now have a pressing mission to ensure that all graduating students fulfil their professional competency requirements. The professional world of architecture is changing and so are its procurement processes. First Nations groups and communities exercise their agency and can demand appropriate architectural services that meet their needs, and Indigenising the curriculum meets this new and welcome reality.

Reflection questions

- How could an awareness and connection to your students’ personal experiences of culture and history help them learn better?

- Could you imagine telling your class a story about your life to model learning through reflection?

- Are you willing to create a teaching space where you are a collaborative learner, lacking expertise or understanding of First Nations people/communities?

- What barriers do you think your teaching team might face if they were to take up storying as a teaching tool?

- Are there any Indigenising the curriculum efforts that your discipline is undertaking and how might you connect with them?

- Have you ever encountered challenging students who are against learning about cultures other than their own? How did you deal with it?

References

Architects Accreditation Council of Australia. (n.d.). Accreditation of architecture programs – Resource: First Nations performance criteria. https://aaca.org.au/https-aaca-org-au-wp-content-uploads-accredited-architecture-qualifications-pdf/

Architects Accreditation Council of Australia. (2021). 2021 national standard of competency for architects. https://aaca.org.au/national-standard-of-competency-for-architects/2021nsca/

Australian Institute of Architects. (n.d.). First Nations resources hub. https://www.architecture.com.au/advocacy-news/policy/first-nations-resource-hub

Bunda, T., Barney, K., Richy, N., Oliver, L., Saunders, R., & Gilbert, S. (2024). Theoretical foundations for storying a knowledge basket: Enhancing student engagement in Indigenous studies in the Australian context. In C. Stone & S O’Shea (Eds.), Research handbook on student engagement in higher education (pp. 380–396). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Fredericks, F., Adams, K., Finlay, S., Fletcher, G., Andy, S., Briggs, L., & Hall, G. (2011). Engaging the practice of Indigenous yarning in action research. Action Learning and Action Research Journal, 17(2), 7–19.

Go-Sam, C. (2023). Recognize cultural safety and cultural load. Architecture Australia, 112(4), 53.

Go-Sam, C., Greenop, K., Marnane, K., & Shaweesh, M. (2024). Gununa futures: A report on housing, energy and town design in Gununa, Mornington Island, Queensland. The University of Queensland.

Go-Sam, C., Philips, C., & Gilbert, J. (2025). Building relationality: Sustaining First Nations aspirations in design studio teaching. Fabrications, 34(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/10331867.2025.2494893

Heynen, H., & Wright, G. (2012). Introduction: Shifting paradigms and concerns. In C. G. Crysler, S. Cairns & H. Heynen (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of architectural theory (pp. 41–55). SAGE Publications Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446201756.n3

Hosagrahar, J. (2012). Interrogating difference: Postcolonial perspectives in architecture and urbanism. In C. G. Crysler, S. Cairns & H. Heynen (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of architectural theory (pp. 70–84). SAGE Publications Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446201756.n5

Hromek, D. (2023). What is cultural safety and how do we design for it? Architecture Australia, 112(1), 68–69.

Memmott, P., & Keys, C. (2016). The emergence of an architectural anthropology in Aboriginal Australia: The work of the Aboriginal Environments Research Centre. Architectural Theory Review, 21(2), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/13264826.2017.1316752

Parlour. (2023). Deadly djurumin yarns. https://parlour.org.au/parlour-live/deadly-djurumin-yarns/deadly-djurumin-yarns/

Phillips, L. G., & Bunda, T. (2018). Research through, with and as storying. Routledge.

University of Queensland, The. (2024). Architectural design: Clients and culture (ARCH3100). https://programs-courses.uq.edu.au/course.html?course_code=ARCH3100

University of Queensland, The. (2024). Graduate statement and graduate attributes policy. https://policies.uq.edu.au/document/view-current.php?id=155

- Carroll was made an Honorary Fellow of the Australian Institute of Architects in 2023, a rare and high honour from the profession’s peak organisation. ↵

- See NSCA performance criteria PC 15: “Understand legal and ethical obligations relating to copyright, moral rights, authorship of cultural knowledge and intellectual property requirements across architectural services” and part of the requirements for PC 27: “Understand how to embed the knowledge, worldviews and perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, shared through engagement processes, into the conceptual design in a meaningful, respectful and appropriate way” (Architects Accreditation Council of Australia, 2021, p. 5–6). ↵

- In the context of architectural design, an explanation of cultural safety is given by Hromek (2023) and an explanation of cultural load by Go-Sam (2023). ↵

- We want to acknowledge the work of all our tutors and that no implication of bad faith is implied in our analysis. All tried hard to engage with the work required. We acknowledge that, in a sense, the storying in studio method was experimental and that additional support to prepare and engage with tutors would be required for future versions of storying in studio. ↵