5 Indigenising the environmental science curriculum: Part 2

In practice

Coen Hird; Jim Walker; Benjamin Mos; and Steven W. Salisbury

School of the Environment

Glossary and Positionality: see companion chapter (part 1).

Introduction

Building on the theoretical foundations of the companion chapter (part 1), this chapter presents practical examples of Indigenising curriculum at The University of Queensland (UQ) Faculty of Science (FoS), focusing on seminars, classrooms, and field teaching, and their associated challenges and successes. These examples have helped to foster cultural awareness and co-designed teaching, forming a foundation for broader implementation across science. As discussed in the previous chapter, these case studies illustrate that Indigenising the science curriculum is a process that needs to go beyond simply creating equity in teaching and learning. In different ways, each case study shows how Indigenisation needs to be about engaging in an ongoing relationship with knowledge that can help transform the nature of science education in the University. It is also about building respect between different knowledge systems and acknowledging that place-based knowledge is a valuable layer of understanding, which can and should integrally inform how science is done.

Case study 1: Lunchbox seminars

One of the most critical concerted efforts to bring Indigenous perspectives into the science curriculum at UQ came through the hire of Jim Walker (Yiman and Goreng Goreng) in the then School of Earth and Environmental Science (now part of the School of the Environment) as a Lecturer. To help achieve this, Jim launched several lunchbox seminars across the FoS, targeted at specific Schools. The seminars had two purposes: first, to gauge the level of cultural awareness among non-Indigenous academics and students; and second, to develop an understanding of the history and politics of Indigenous Australia. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander educators often understand this through lived realities, but many non-Indigenous staff lack this knowledge or avoid engaging. Indeed, poor understanding of colonial history and its impacts for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples among teaching staff is a substantial impediment to Indigenising curricula across the Australian tertiary sector (Murray & Campton, 2023). Importantly, the seminars were founded on the belief that, if we are to change the way in which Western science engages with Indigenous Nations, then this change needs to be grounded within the science curriculum.

The lunchbox seminars led by Jim were educational and critical to breaking down some of the barriers for non-Indigenous academics to engage with Indigenising curriculum and to encourage a questioning mindset as to how Indigenous knowledges could be centred within the existing science curriculum. This aspect of Indigenising curriculum, building cultural knowledge, is important because Indigenising the science curriculum requires a commitment from non-Indigenous Faculty staff to participate. Jim also identified that students need to see the goodwill that non-Indigenous educators have towards Indigenising curriculum, otherwise they may risk projecting a divided teaching team which inhibits student buy-in. This started with conversations and networking, building relationships, and advocating for undertaking continual training and education around cultural awareness.

The seminars aimed to inform non-Indigenous academics around the traumatic history of Aboriginal Australia, and bring up the concepts of racialisation and the historical and contemporary racial discrimination against Indigenous peoples in Australia. Seminar topics included the destruction of Country and intergenerational trauma. However, the lunchbox seminars also introduced participants to a rights-based approach to Indigenous engagement in science by introducing the concept that Indigenous peoples are not merely stakeholders in scientific research but rather they are rights-holders (see discussions in the companion chapter on epistemic violence). This means Indigenous peoples are a mandatory inclusion in decision-making governance in any science research that incorporates their traditional knowledges, genetic resources, traditional cultural expressions, and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) (World Intellectual Property Organization, 2024).

The lunchbox seminars introduced staff and students to international legal frameworks such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the Nagoya Protocol (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2011) and the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (International Labour Organisation, 1989). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups across Australia are asserting sovereignty as First Nations communities over research and engagement, demanding recognition of their rights through ethical research agreements (Austin et al., 2019; Lincoln et al., 2017). In accordance with these international agreements, it was emphasised that research agreements with Indigenous peoples should, at a minimum, address free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), access and benefit sharing (ABS), and mutually agreed terms. A useful tool for understanding Indigenous rights in research was developed by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, the AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research (AIATSIS Code). Universities are currently grappling with how to operationalise the AIATSIS Code. At an institutional level, they may adopt a narrow interpretation that engagement is only required when research explicitly involves Indigenous peoples, knowledges or practices. However, the AIATSIS Code can be interpreted more broadly to suggest that, because all research occurs on Indigenous lands, there is an ethical obligation for engagement with relevant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. This broader interpretation aligns with the expectations of many First Nations communities, who maintain that all research should commence with an opportunity to refuse, consult or participate within ethical models of engagement.

Tip

Tip

Do your research to understand who all the relevant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are on the Country you are working in. This is not always obvious. There are many layers to Indigenous communities, from an individual up to a Registered Native Title Body Corporate (RNTBC) or Indigenous corporation, business or company. As a result, there are many ways in which academics, researchers or students can engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. As such, it is also important to understand that there are specific regulations that can predetermine who is the right Aboriginal party or person/s for a particular area.

The seminars employed a trauma-informed pedagogy (Carello & Butler, 2013; Thompson & Marsh, 2022). For many participants, it was their first exposure to these issues, while Indigenous attendees may have revisited traumatic experiences. Jim was gentle with how he guided participants and did not dig too deeply into trauma. The seminars built in moments of silence and safety, using empathy to acknowledge the trauma that is associated with the educational material. These deeper connections with non-Indigenous scientists allowed deeper understandings to grow than what might typically be possible using online cultural competency tools. Once taught some of the history, a better understanding of why Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples may not necessarily be so accepting of dominant narratives in science and science research grew, while showing that fears the participants may have had were unfounded where engagement centres respect for all parties.

Case study 2: Classroom teaching

Teaching modules

From 2022 to 2024, Jim developed several teaching modules that were integrated into courses across science programs, with particular emphasis on the Bachelor of Environmental Management program at UQ (Table 1). The Indigenising modules were bespoke lectures that linked Indigenous knowledges to the specific discipline, but firstly centred education around Indigenous knowledge systems. The framework for many of these lectures had been developed previously as bespoke lectures for other courses (e.g., BIOL2001 Australia’s Terrestrial Environment for Steve Salisbury, 2009 to 2011). The impetus for embedding these modules was to tell histories that had not been told, or had been silenced, from Indigenous perspectives. Reflective modules prompted feedback such as “I’ve never thought about it that way”, helping students see Indigenous knowledges as distinct systems rather than erroneous translations through a Western lens. Like others, Jim observed that the integration of Indigenous knowledges with Western science is a matter of debate. But as a bare minimum, there should be a learning outcome that students come into the realisation that there are multiple knowledge systems tied into the course topic.

Table 1: Modules developed by Jim Walker for FoS courses

| Course code | Course title | Module |

|---|---|---|

| BIOL2001 | Australia’s Terrestrial Environment | Australia’s First Peoples |

| BIOL3204 | Plant Adaptation & Global Change | Indigenous View on Plants and Ecosystems |

| ENVM2100 & 7100 | Foundations of Sustainable Development | Indigenous Participation in Sustainable Development |

| ENVM3103 & 7123 | Regulatory Frameworks for Environmental Management & Planning | Community Engagement in Environmental Management and Planning – A First Nations Perspective in Australia |

| ENVM3220 & 7202 | Conservation Planning & Management | Indigenous Land and Sea Management |

| ENVM3506 & 7505 | Conservation Policy | Indigenous Perspectives in Conservation Policy |

| ENVM7206 | Tools for Environmental Assessment & Analysis | Social-Cultural Impact Assessment: Indigenous Peoples’ Perspectives on the Environment |

| ERTH3104 | Tectonics | Australia’s First Peoples and Geology |

| FOOD 3022 & 7022 | Bush Foods of Australia | Indigenous Traditional Knowledge – Issues of Research and Protection |

| GEOS2105 | Geography of Australia | Northern Frontier – Indigenous Contributions to Northern Australia; First Nations Peoples of Australia: Before the Dugai |

| GEOG3000 | Regional Economic Development Planning | Regional Development and Indigenous Australia |

| MARS3012 | Physical-Biological Oceanography | Human-Oceans Interactions (Indigenous Land and Sea Perspectives) |

| PLAN1100 | Foundational Ideas for Planning | Indigenous Considerations in Planning |

| PLAN2000 | Urban Design Studio | Indigenous Issues in Urban Design |

| PLAN3000 & 7126 | Plan Making | First Peoples Perspectives of Urban Regeneration: Exploring Case Studies of Redfern and Fitzroy |

Indigenous knowledge systems

The modules developed by Jim unsettled students’ Western science education to facilitate understanding that there are multiple knowledge systems operating in so-called Australia (i.e., epistemological plurality; see companion chapter). Coen (trawlwoolway), an Associate Lecturer in the School of the Environment extended this strategy while producing content for the course Wildlife Technologies. Coen developed a series of transferable lectures that communicate to students the importance of seeing Indigenous knowledge systems through “fresh eyes, unfiltered by the polarised lenses of Eurocentric worldviews, metaphysics, epistemologies, values and ideologies” (Aikenhead & Okagawa, 2007, p. 552) that underpin Western sciences taught in Australian schools. This is important, because Indigenous knowledges are not simply expressed through a teacher-directed curriculum as fact pedagogy, which dominates tertiary science education, but rather as active, performative, narrated and embedded in local contexts (Nakata et al., 2014).

Tip

Tip

Build student confidence through structured introductions to Indigenous knowledges.

The first lecture introduced students to paradigms of inquiry (Bibi et al., 2022) and reflexivity to unsettle students’ epistemic grounds. Using the Mentimeter application, students rated their resonance with statements such as “There is a single objective reality” or “There are multiple subjective realities”. This exercise lets students see the diversity of opinions that exist within their own cohort and begin to critique what ontological and epistemological assumptions underlie their scientific discipline. Here, a pedagogy of discomfort is applied (Millner, 2021) to provide students with a way to scaffold discussions of colonial history and contemporary colonial geographies in science and knowledge production (Hird et al., 2023). Students were reassured that discomfort and uncertainty are intentional and advised not to “understand too quickly” (Lyndon Murphy and Norm Sheehan, personal communication.). In other words, if students left with more questions than when they came in, the lecture had its desired effect. Students were reminded that they are not expected to become experts in philosophy and sociology, particularly as environmental science students, reflecting the need for reflexivity and humility discussed in the companion chapter. But throughout the lecture, there is explicit clarity about what aspects of the lecture are assessable with assurances that, despite ambiguity, students will still likely achieve well in the course. This worked to foster an intellectual humility to discuss Indigenous knowledges. Students were informed that the content, while unfamiliar, forms part of the graduate attribute of cultural capability that UQ students are expected to develop throughout their degrees (see the companion chapter).

The first lecture sets the groundwork for a second lecture on Indigenous Data Sovereignty (IDSOV) and ICIP. Here, callbacks to the first lecture were repeated as issues of IDSOV are linked back to different worldviews and epistemologies. The question of the cultural relevance of objective biological data is interrogated, using data collected from drones in cultural mapping exercises as a key example. Importantly, these two lectures are broadly applicable across the FoS and can be co-opted to appear as foundational first-year learning that subsequent courses can scaffold from within the science curriculum. However, a spiral approach to embedding Indigenous content might involve repeating such content over the years as an effective Indigenous pedagogy (Yunkaporta & McGinty, 2009). Only in the third and final lecture were disciplinary topics introduced (Indigenous wildlife technologies). With the first two lectures in the foreground, students were better equipped to learn about Indigenous technologies without solely critiquing them through a Western science lens. This is a fundamentally transformative pedagogy, causing students to reflexively and reflectively examine their own beliefs and values, and fostering an appreciation for pluralistic expressions of knowledge (Bullen & Flavell, 2017; Khedkar & Nair, 2016; Mudaly & Ismail, 2013).The teaching approach used by Jim and Coen also engages with the cultural interface as a pedagogical framework (Carey & Prince, 2015; Nakata, 2007) by unsettling science learners around definitions of science and Indigenous science, scientific realism and structuralism, and pluralistic epistemologies and ontologies that inform scientific assumptions. This is done in several ways, such as interrogating the question “What is Country?” through both Western and Indigenous lenses. In Western epistemes, “country” is mostly understood by students as the environment, whereas, in Indigenous worldviews, “Country” is often capitalised and encompasses the human and spiritual worlds in addition to the natural world. To illustrate the complex nature of seeking to understand Indigenous knowledges, students briefly explored Aikenhead and Okagawa’s (2007) assertion of Indigenous and Western science as a false dichotomy by critiquing (rather than criticising) the popular comparison of “Traditional native knowledge” and “Western science” (Stephens, 2000). We, as educators, should be considering what level of meta-awareness is needed for students to “become knowledgeable about the existence of different ways of learning, knowing and doing and to feel their way confidently along” (Nakata, 2010, p. 56). In this context, it is important to recognise that Indigenous knowledge holders exist mostly outside of the academy, and lecturers should be seen as facilitators of knowledge rather than absolute sources. For example, Coen’s lectures did not explicitly teach Indigenous knowledges but rather guided students on a journey to better understand what Indigenous knowledges are in the first instance. To this end, lectures were complemented with podcasts (e.g., Barney & Bunda, 2024), readings and video talks from Indigenous intellectuals and knowledge holders.

Case study 3: Field teaching

Central to the development of teaching on Country is building meaningful and lasting relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – an unfortunately rare pursuit for science academics (Cawthorne, 2023). This praxis is vital for illustrating Indigenous rights and countering students’ transactional approaches to tertiary education (Bullen & Flavell, 2017; Tomlinson, 2014). These efforts have culminated in an understanding that part of Indigenising curriculum is to transform the culture of science education in this place. The success of the examples of field teaching described below were underpinned by a growing realisation from Faculty staff and the School Executive that relationship building and maintenance are a priority; finances and resources must be allocated to achieve these goals, and the development of the curriculum with Indigenous peoples should not be transactional.

The UQ Indigenising curriculum: Consultation Green Paper (Bunda, 2022) identifies Country as a central design principle, particularly relevant in field teaching. This is because the experiential learning that occurs during field trips (Harrison et al., 2017) in environmental science is straightforward to link with Indigenous place-based pedagogy (Yunkaporta, 2023), as the natural environment forms a basis of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kincentric and relational worldviews. As a pedagogical technique, it also means that knowledge sharing and experiences around learning can be linked to experiences of place and people (Rossiter, 2002). However, it is important to note the false equivalency that is often prescribed to Country and the “field”, which can inadvertently imply that urban areas are not Country. Although urban areas are highly modified, they still maintain a set of relationships with more-than-human kin (Abram, 1996, p. 9) and are sites of continued cultural importance. In this context, as is the case for every UQ campus, campus is Country (Darug Ngurra et al., 2021), even in the most advanced laboratories. Wilson and Schellhammer (2021, pp. 45–47) assert that Indigenous pedagogies do not just remove students from campus, but rather explore deeper learning concepts around Country.

BIOL2001 Australia’s Terrestrial Environment and BIOL2015 Ecology Field Studies

Since 2006, UQ has been taking undergraduate ecology and environmental science students to K’gari (Fraser Island) on Butchulla Country. These field trips started with BIOL2001 Australia’s Terrestrial Environment, a second-level course for Study Abroad students (mostly international students in Australia for six months). The BIOL2001 field trip to K’gari happened twice a year and ran from 2006 through to 2019, with virtual field trips running through COVID-19 during 2020 and 2021. A second course, BIOL2015 Ecology Field Studies, started in 2009. The BIOL2015 field trip happens once a year, and was initially modelled on the BIOL2001 field trip, but caters specifically for domestic students majoring in ecology and related disciplines. Although BIOL2015 was also interrupted by COVID-19, it continues. Steve Salisbury coordinated BIOL2001 from 2006 to 2021 (sharing coordination with Bryan Fry from 2018 to 2021) and has been part of BIOL2015 since 2022. These courses have become the centrepiece of UQ’s undergraduate ecology teaching program and are the highlight of the semester for many of the students who participate in them.

UQ’s teaching on K’gari has been based out of Dilli Village, an old sand-mining camp from the early 1970s that is now a campground and educational facility run by the University of the Sunshine Coast at the southern end of K’gari’s east coast. Students explore the foredune complex, bushland, freshwater lakes, sclerophyll forests, rainforests, and nearby mangroves, learning how sandy soils shape habitats.

Like many undergraduate ecology courses, both BIOL2001 and BIOL2015 initially introduced students to a range of non-lethal trapping methods commonly used by ecologists to sample for terrestrial vertebrates (see Garden et al., 2007; Tasker & Dickman, 2001). Elliott traps, drift fences, pitfalls and herp-funnels were used to capture invertebrates, frogs, small lizards, rodents and small marsupials. Hair traps were also used to collect hair samples from wongari (dingoes), bandicoots and rodents. A small number of these traps were set each evening and checked the following morning. Animals were handled and identified by students before being released. Invertebrates were also collected and identified, along with samples of plants from different habitats. A range of non-intrusive observation only survey techniques were also employed, including birdwatching, plant identification, examining animal tracks and traces in the sand, and looking at the soil. In some instances, non-baited camera traps were also deployed.

Since its World Heritage listing in 1992, most of K’gari has been managed by the Queensland National Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS). Under the Nature Conservation Act 1992, any educational or research activities undertaken on K’gari require a scientific research and educational purposes permit. In addition, for BIOL2001 and BIOL2015, such activities also require an ethics permit from UQ’s Animal Ethics Committee.

K’gari forms part of the traditional lands of the people of the Badtjala language group (also spelt Butchulla; the latter is the phonetic spelling, whereas the former is not. See Foley, 1996). Badtjala traditional boundaries include the geographical landmarks of “Fraser Island, Double Island Point, Tin Can Bay, Bauple Mountain and north to a point at the mouth of Burrum Heads” (Reeves, 1964, p. 48). In late 2014, the Federal Court of Australia handed down a determination that recognised the Butchulla people’s non-exclusive native title rights and interests over K’gari (Federal Court of Australia, 2014). The bundle of rights associated with this native title determination has given back to Butchulla people a means to enjoy and protect their traditional lands and waters and to explore opportunities for economic development.

As best as possible, and where appropriate, BIOL2001 and BIOL2015 students were made aware of K’gari’s Indigenous cultural heritage. Before the 2014 Butchulla native title determination, UQ’s engagement with Butchulla on K’gari was minimal, and likely limited to Shirley Foley and Fiona Foley. If there was engagement with other Butchulla people across other parts of UQ, the School of Biological Sciences was not aware of it. For academic staff such as Steve, who had worked closely with Traditional Custodians in the Kimberley since 2010 (see Salisbury et al., 2017), there was a growing sense of unease about visiting K’gari without the consent or involvement of its Traditional Owners.

In March 2019, Steve reached out to Butchulla Aboriginal Corporation (BAC), the Registered Native Title Body Corporate (RNTBC) established in 2014 to manage the native title rights of Butchulla people on K’gari. (A separate RNTBC, Butchulla Native Title Aboriginal Corporation, was set up in 2019 for the Butchulla people operating principally on the mainland). From the onset, the goal was to seek the consent of BAC about any proposed teaching activities that UQ undertook on K’gari, and to let them guide how the students and teaching staff engaged with Butchulla cultural heritage. As best as both parties are aware, this was the first time a university had reached out to BAC to seek their involvement in teaching activities on K’gari. At the time, it was simply seen as the most respectful way to start the engagement process. Looking back, neither Steve nor the representatives from BAC that he was engaged with were aware of the concept of co-design.

Another factor that precipitated engagement related to the permitting process with QPWS and, at the time, the Queensland Department of National Parks, Sports and Racing. Steve learned that QPWS-managed areas with native title required permit applications to include Traditional Owners’ consent. Since Butchulla had non-exclusive native title rights to K’gari, this meant that new permit applications for activities on the island required the consent of BAC. At the time, this was one of the few areas around “co-management” that gave BAC a say in how their Country was managed.

Part of the initial conversation between Steve and BAC involved the former admitting that he thought it was likely that some of the activities UQ had been undertaking under previous teaching permits (e.g., live-trapping small mammals, collecting insects, etc.) may not be considered culturally appropriate by Butchulla. There was also a concern that students were unknowingly being taken to culturally sensitive locations. These concerns were confirmed by BAC in the discussions that followed and opened the way for re-designing some of the activities. When it came to informing the students about aspects of Butchulla cultural heritage, Steve also expressed his desire for this process to be led by BAC. There was a desire to follow cultural protocols such as having the teaching groups being Welcomed to Country upon their arrival to the island. BAC members were happy to accommodate these wishes and consider more culturally safe ways for the students to learn about K’gari and Butchulla. If there were ways that UQ could help BAC in achieving their goals, these opportunities could also be explored.

Since the initial point of engagement in 2019, Butchulla people, culture and Country have become tightly woven into the delivery of not just BIOL2001 and BIOL2015, but also some of the School of the Environment’s international contracts programs (for example, with Stanford University once a year since 2022) (Figures 1– 4, 9). The degree to which BAC has been involved in each of these courses has varied annually, depending on people’s availability and capacity, and around budgetary constraints. Prior to collaborating with each other, neither the School of Biological Sciences nor BAC had any experience engaging in this type of co-designed activity.

Figure 2: Butchulla Traditional Owner Luke Barrowcliffe cleanses BIOL2001 tutors and students with she-oak branches, April 2019 (YouTube, 7s).Video footage © Steve Salisbury.

Over the years, it has become apparent that while most aspects of Butchulla cultural heritage are best delivered by Butchulla people on Country (Figures 1–4, 9), the right people may not always be available to talk about certain things. It can also be beneficial for students to have a basic level of knowledge before they get to K’gari, and learning about K’gari in preparation for their visit needs to involve an understanding of and respect for the island’s Traditional Owners. To this end, before the field trips begin, students attend a compulsory workshop to explicitly discuss the cultural dimensions of the K’gari field trip.

Figure 3: Butchulla Traditional Owner Jade Gould leads BIOL2001 students past Lake Boomanjin, K’gari, April 2019 (YouTube, 12s). Video footage © Steve Salisbury.

Tip

Tip

Develop and share co-designed resources, such as induction videos, with community in areas where teaching and research activities may occur.

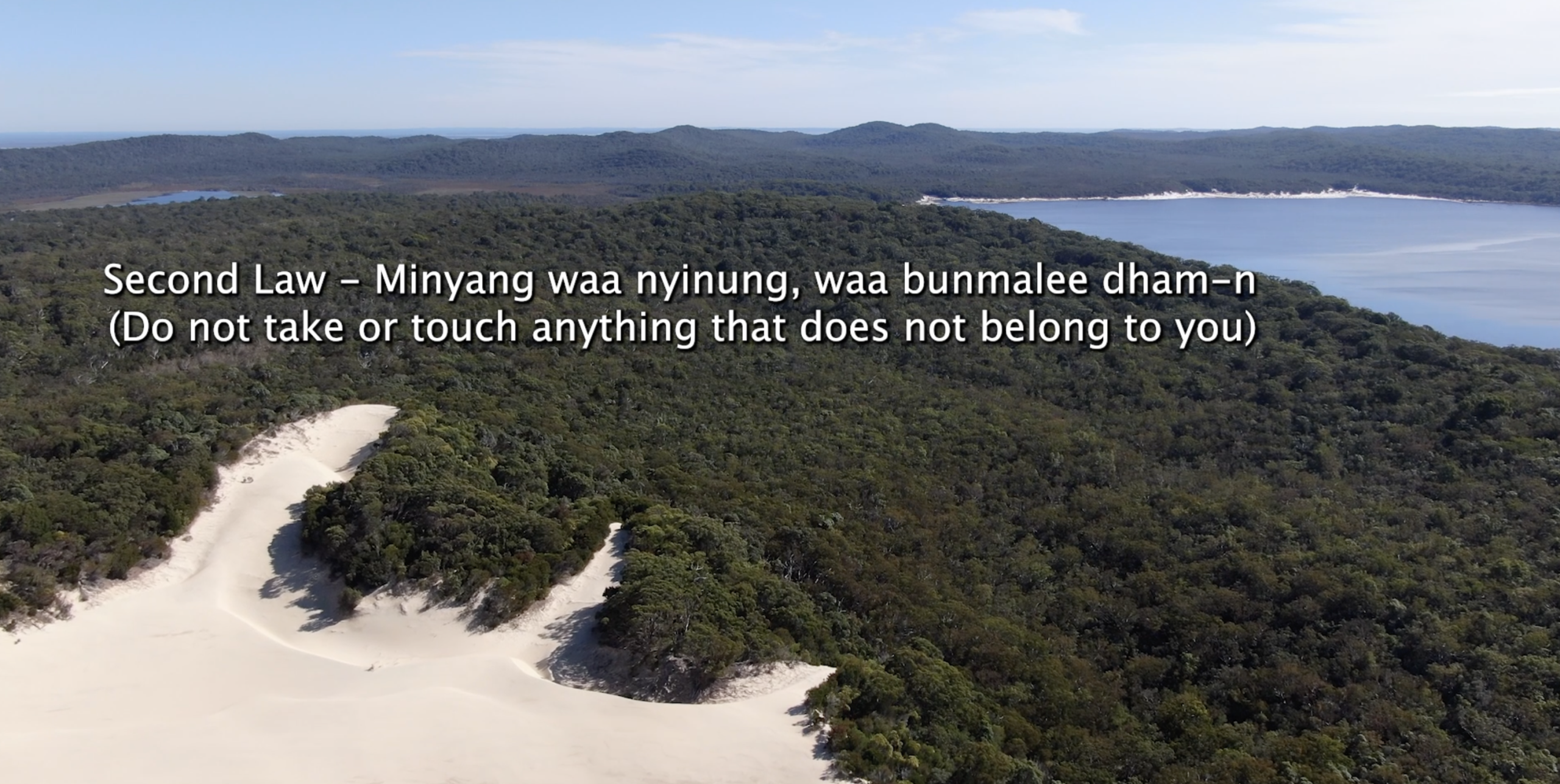

From 2019 to 2023, the School of Biological Sciences collaborated with BAC to produce a cultural induction video featuring discussions with Butchulla Elders about K’gari, Butchulla culture, Butchulla law and lore, and directives for behaviour on K’gari (Figures 5–7). Funding for the video project came from UQ, awarded to Professor Susanne Schmidt in 2019. The script for the video was written by the then Butchulla Director, Jade Gould, with input from Steve Salisbury and Susanne Schmidt. All the interviews with Butchulla people were filmed by Jade. The current version of the video includes footage of Aunty Joyce Bonner, Aunty Roslyn Howden, Aunty Frances Gala, Uncle George Gala, Conway Burns, Blayde Foley, Jodie Rainbow, and Wayne Tobane, and a voiceover from Jade towards the end. Anthony O’Toole edited the video, adding additional footage from past UQ visits to K’gari, including a Welcome to Country by Wayne Tobane for the BIOL2015 students in 2022 that he gave permission to use. A couple of historical photos from the Queensland State Archives were also added to the section about colonisation. Given that the video was intended to be used specifically for UQ students as part of their preparation for visiting K’gari, it is only shown with the consent of BAC. To this end, it has not been made publicly available for a wider audience, although this option is always open to BAC should they so choose. For the purposes of preparing students for their time on the island, the video has proven invaluable.

Recently, the pre-field trip workshop has also included a presentation from Associate Professor Fiona Foley, a proud Badtjala woman and globally renowned Indigenous artist, to discuss the history of The Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act, 1897 and the history of opium use, not just by Badtjala people, but other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples all over the state (see Foley, 2020). Fiona shone a critical light on the little-known colonial-era practice of paying Indigenous workers with opium ash, and the “solution” of then displacing them to the Aboriginal mission at Bogimbah Creek, on the west coast of K’gari (Foley, 2021). Students were shown Fiona’s 2019 short film about the Act, Out of the Sea like a Cloud, and learnt about her late mother, Shirley Foley, and her work to create a Badtjala–English / English–Badtjala dictionary (Foley, 1996).

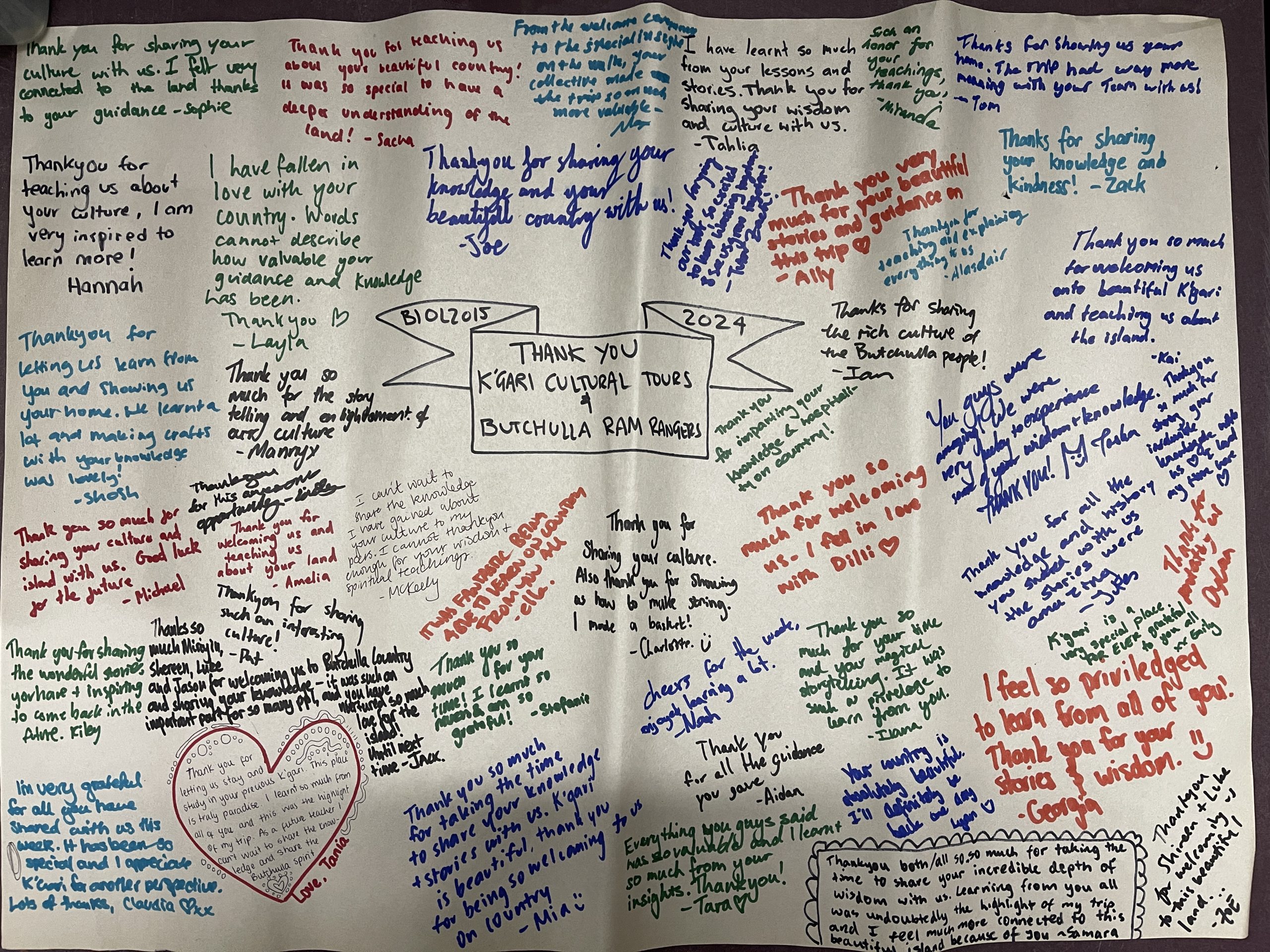

During the field trips, Butchulla Traditional Owners were engaged to provide a Welcome to Country and Smoking Ceremony when UQ teaching teams arrived on K’gari. Following this, they yarn (Bessarab & Ng’andu, 2010) with the students and teaching team about the history of K’gari, Butchulla culture and connection to Country. Initially, these activities were carried out by Directors from BAC and Butchulla Land and Sea Rangers (BLSR). As the capacity of BAC has grown, however, the organisation has created Butchulla Enterprises Limited (established 2022), under which K’gari Cultural Tours (KCT) now operates. At the time of publication, UQ engagement activities on K’gari have primarily been handled through KCT, with ongoing involvement with BLSR when they are available (Figures 4, 8, 9). Importantly, Butchulla Traditional Owners are paid for their time through these organisational arms of BAC with which UQ now works. All profits from these programs and initiatives are reinvested into the Butchulla community, supporting cultural preservation and development.

During the field trip, students undertake a range of ecological survey activities in line with the non-intrusive, observational-only techniques introduced in 2018–19, as these are regarded as culturally appropriate by Butchulla. Importantly, BLSRs often accompany the students as they visit various parts of K’gari, allowing for organic knowledge exchange throughout the course of the day (Figures 4, 9). Through this, students see clearly how much knowledge Butchulla people have of their Country and learn to link the experience of learning about Butchulla culture with people and places (Figures 4, 9). Indigenous worldviews are often kincentric and relational (Martinez et al., 2023; Moreton-Robinson, 2017), contrasting with epistemologies of Western science. Being exposed to these worldviews allows students to interface with Indigenous knowledges as separate from Western scientific objectification of nature. Within Indigenous epistemologies, Country is a teacher. In other words, Country is pedagogy (Harrison et al., 2017; Harrison & Skrebneva, 2020; Simpson, 2017). These pedagogies facilitate experiential learning, a key component of field trips in environmental science and other disciplines (Sobel, 2017). Significantly, the integration of Indigenous knowledges, ways of knowing and the centrality of Country within the field trips is transforming how other aspects of field ecology are being taught and conducted afterwards in other contexts.

Tip

Tip

Treat Country as a co-teacher.

The presence of Butchulla Traditional Owners on the UQ ecology field trips to K’gari serves multiple purposes. Firstly, it foregrounds respect for Indigenous sovereignty and cultural protocols by placing the power of how education happens on Country in the hands of relevant Indigenous peoples. Committing to real power sharing in this context requires flexibility on the teacher’s behalf to not dictate what the learning experience looks like and letting things unfold naturally. Secondly, it allows Indigenous knowledges to be taught from, of, and on Country through Aboriginal knowledge holders, a pedagogy termed “Indigegogy” (Wilson & Schellhammer, 2021).

BIOL1030 Biodiversity and the Environment

Other courses within the FoS also include Indigenous voices and perspectives in various parts of field trips. One such course is BIOL1030 Biodiversity and Environment, a foundational first-level course that aims to introduce students to concepts in biodiversity, ecology, biogeography and evolution by examining global challenges such as emerging diseases, species extinction and sustainable populations. The course typically has an enrolment of around 350 to 400 domestic students. Steve has been teaching in BIOL1030 since 2022 and started coordinating it in 2023. Coen Hird had a tutoring role in 2021–2022 and assisted with Indigenous engagement.

In 2022, BIOL1030 introduced an overnight field trip to Springbrook plateau, one of the more spectacular remnants of the northern flank of the Tweed Volcano, with Wollumbin at its centre. Much of the plateau falls within Springbrook National Park, which is part of the Gondwana Rainforests of Australia World Heritage Area on the Queensland–New South Wales border. The new field trip to Springbrook plateau provided an ideal opportunity to apply some of the lessons learnt from Indigenous engagement in field ecology courses on K’gari to a larger student cohort in a different location. The Springbrook plateau is a culturally significant area to several Indigenous communities. Steve and Coen decided to engage with members of Ngarang-Wal Gold Coast Aboriginal Association Incorporated (NWGCAAI) as representatives of various Kombumerri/Ngarang-Wal families with connections to Springbrook. Although Kombumerri/Ngarang-Wal are saltwater people, Springbrook plateau is an area of high cultural significance to them and is known as Medicine Man Mountain. The engagement with NWGCAAI commenced early in the planning process, to allow for co-design of the field trip. This influenced Steve and Coen’s decisions around what educational activities were undertaken, such as sampling animals and vegetation. By centring the wishes of NWGCAAI, anything sampled and collected on Country during the field trip was returned to Country (in this instance, leaf litter for the identification of invertebrates). Students are told about the design of the activities by teaching staff and representatives from NWGCAAI, and in the process are shown that Indigenous sovereignty was fundamental to developing the field trip.

Tip

Tip

Co-design teaching activities based on community priorities and protocols.

Due to high enrolment, the course runs over multiple days, with 3 to 4 groups of 100 students attending for 24 hours each. Upon arrival, each group of students was Welcomed to Country by NWGCAAI’s Kombumerri Rangers. Senior rangers then engaged in an hour-long presentation with students about their cultural heritage, the history of the land and how they are connected to it. Importantly, the UQ teaching team did not dictate what the students would be taught during this presentation, and it can vary for each group. There is time afterwards for the students to yarn with the rangers and examine a display of books, art, local artefacts and items of cultural significance (Figure 11). The students then split up into smaller groups and either conduct some basic ecological survey work or undertake a seven kilometre bush walk through the national park.

Acknowledging that the Kombumerri Rangers are unable to be present during the entire time students visit Springbrook plateau, a plan was developed to enable tutors to appropriately share aspects of Indigenous cultural knowledge. The day before the first group of students arrive, members of the teaching team (academic staff, technical staff and tutors) meet with Kombumerri Rangers. Together, the group does the same walk that the students will do with the tutors during the field trip (Figure 12). This walk allows the groups to get to know each other, and to share knowledge and experiences. Importantly, the rangers can instruct the tutors about what sorts of knowledge they can share with the students. When sharing any of this knowledge with the students, it is clearly communicated that the tutors have a responsibility to share how it is that they came to know it and that they have been given permission to share it with the students. In this way, both the tutors and the students participate in a form of knowledge-sharing that is consistent with cultural protocols that are also followed by Kombumerri/Ngarang-Wal families.

Like the on Country teaching experience with Butchulla, the BIOL1030 Kombumerri/Ngarang-Wal program has grown considerably since it commenced in 2022. It provides a culturally safe space where the Kombumerri Rangers and other Kombumerri/Ngarang-Wal families can gain confidence engaging with large groups to share aspects of their cultural heritage. In 2023, the BIOL1030 visit included one of the first public performances of Kombumerri Elebana Kunjiel (meaning “beautiful Kombumerri dance”), a dance troupe funded and supported by NWGCAAI families and Kombumerri Elders. Elebana Kunjiel was given permissions through family links to Minjerribah Moorgumpin Elders in Council to share dance and song as part of their routine. Seeing the newly formed Kombumerri Elebana Kunjiel perform for BIOL1030 for the first time as part of the Welcome to Country was a proud and powerful moment for everyone present (Figures 13). The group has gone on to give regular performances at schools and public events across the Gold Coast for NWGCAAI.

ANIM3018 Wildlife Technologies

Commencing in Semester 2, 2024, another field course in the FoS where Indigenous voices and perspectives are now highlighted is ANIM3018 Wildlife Technologies. Following a series of lectures introducing Indigenous knowledges and IDSOV, the ANIM3018 students went on a field trip to Guanaba Indigenous Protected Area (GIPA). The field trip to GIPA was facilitated through existing relationships with NWGCAAI (see BIOL1030 above). A site visit with the teaching team was made to discuss the priorities of Kombumerri Rangers at GIPA around management. A co-designed plan for sampling priority species was developed with Kombumerri, sharing the technologies the University had available for the field trip to ensure mutual benefit in the project.

Tip

Tip

Embed relational accountability in your practices when working with community.

Because of the co-design process with Kombumerri Rangers, students actively participate in a community project-based field trip which feeds into their assessment. At GIPA, students have the rough locations for deploying technology dictated by rangers, but they are left to read Country themselves to decide the final locations. In this context, Country is teacher (Harrison et al., 2017) and teachers/tutors are present as “knowledgeable, reflective participants” with an active role, rather than as passive “program operators” (Serafini, 2000, p. 389). Further to this, students participate in yarning (or a yarning-informed pedagogy), where students are invited to participate in non-hierarchical conversations with teaching staff and Indigenous rangers that subvert dominant teacher–student relationships and engage in social constructivist learning (Bessarab & Ng’andu, 2010). In this way, Indigenous knowledges are presented by knowledge holders in a style that seeks complementarity to the presentation of Western disciplinary knowledge (Antoine, 2017; Harvey & Russell-Mundine, 2019). The assessment piece was framed as a report that Kombumerri Rangers commissioned students to write about surveying animals at GIPA. However, there are some non-traditional assessment methods employed. Students are asked to consult recent literature on IDSOV and ICIP to design a draft data management plan (for further co-design with Kombumerri Rangers) for the data they collected at GIPA that acknowledges the cultural significance of the location and animals involved. Another part of the assessment includes a component that asks students to provide recommendations through a relational framework, which does not privilege Western epistemological and ontological positions in wildlife management. This creates an unsettling experience for students, when their worldviews are not privileged, by creating Derridean “flips” in the assessment language (Derrida, 1976). Jacques Derrida (1976) inverted traditional hierarchical positions in Western philosophy to reveal their hidden assumptions and limitations (e.g., speech/writing, presence/absence, nature/culture). The flip used here exposes how Western epistemologies are traditionally privileged over Indigenous epistemologies in contemporary scientific training, highlighting that both terms are entangled in complex ways. Students analysed a scenario involving a conservation organisation collecting data on culturally significant species without consulting Traditional Owners. With no experience in the area, the director of the organisation contacts the student in the scenario who has indicated they have training in IDSOV from university to explain how the organisation could do better in the future by following collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, and ethics (CARE) principles (Carroll et al., 2020).

The final part of the assessment requires students to reflect on their own learning journey within the Indigenous modules while evaluating the criteria by which their work is judged for consideration in the development of future rubrics. This self-reflective/reflexive component asked students to interrogate their understanding of how their worldviews and discipline-specific epistemologies tolerated pluralistic worldviews (e.g., how uncomfortable they were with the content and how transformative it was to their thinking). This represented a key step to subvert transactional Western quality indicators to learning and teaching, instead providing indicators of the unlearning required for students to develop cultural capabilities and effectively engage with Indigenous epistemologies in academia (Bullen & Flavell, 2017).

Most students acknowledged moments of discomfort but felt the content enhanced their respect for Indigenous cultures and knowledges. Students reported that the Indigenous module was an interesting and foundational component of the course, and the discipline more broadly, and appreciated a different way to think about environmental data through the lens of IDSOV. Many students reported that it was the first time in their studies that they had been introduced to Indigenous perspectives or interacted with Indigenous peoples. Some students discussed how there was unlearning, in that the content challenged their views on how knowledge is produced, when previously they assumed scientific knowledge was very black and white. Overall, students reported a transformation of their awareness of Indigenous ways of knowing into an appreciation and respect that they will take into the workforce.

Acknowledgements: see companion chapter (part 1).

Reflection questions

- What does Country as pedagogy mean to you? How might it reshape understandings of science education?

- How can you work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and knowledge holders to co-design teaching and learning experiences that centre Indigenous knowledges?

- What has been your own experience of unlearning in relation to Indigenous knowledges? How could this be scaffolded for students?

- How will you acknowledge and address the ways that Indigenous knowledges counter and transform the Western knowledge that has been both dominant and privileged in your discipline?

References

Abram, D. (1996). The spell of the sensuous: Perception and language in a more-than-human world. Pantheon Books.

Aikenhead, G. S., & Ogawa, M. (2007). Indigenous knowledge and science revisited. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 2, 539–620.

Antoine, D. (2017). Pushing the academy: The need for decolonizing research. Canadian Journal of Communication, 42, 113–119.

Austin, B. J., Robinson, C. J., Mathews, D., Oades, D., Dobbs, R. J., Lincoln, G., Wiggan, A., Bayley, S., Edgar, J., King, T., George, K., Mansfield, J., Melbourne, J., & Vigilante, T. (2019). An Indigenous-led approach for regional knowledge partnerships in the Kimberley region of Australia. Human Ecology, 47(4), 577–588.

Barney, K., & Bunda, T. (2024). Using podcasts in higher education: Examples of strategies to Indigenise higher education curricula and to promote Indigenous student success. A practice report. Student Success, 16(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.3381

Bessarab, D., & Ng’andu, B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 3(1), 37–50.

Bibi, H., Khan, D., & Shabir, M. (2022). A critique of research paradigms and their implications for qualitative, quantitative and mixed research methods. Webology, 19(2), 7321–7335.

Bullen, J., & Flavell, H. (2017). Measuring the “gift”: Epistemological and ontological differences between the academy and Indigenous Australia. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(3), 583–596.

Bunda, T. (2022). Indigenising curriculum: Consultation green paper. Office of the Pro Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement) and Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation, The University of Queensland.

Carello, J., & Butler, L. D. (2013). Potentially perilous pedagogies: Teaching trauma is not the same as trauma-informed teaching. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15, 153–168.

Carey, M., & Prince, M. (2015). Designing an Australian Indigenous Studies curriculum for the twenty-first century: Nakata’s “cultural interface”, standpoints and working beyond binaries. Higher Education Research & Development, 34, 270–283.

Carroll, S. R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodríguez, O. L., Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S., Parsons, M., Raseroka, K., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., Rowe, R., Sara, R., Walker, J. D., Anderson, J., & Hudson, M. (2020). The CARE principles for Indigenous data governance. Data Science Journal, 19(43), 1–12.

Cawthorne, M. (2023). Indigenising the Australian university science curriculum [Master’s thesis]. Macquarie University.

Darug Ngurra, Dadd, L., Norman-Dadd, C., Graham, M., Suchet-Pearson, S., Glass, P., Scott, R., Narwhal, H., & Lemire, J. (2021). Buran nalgarra: An Indigenous-led model for walking with good spirit and learning together on Darug Ngurra. AlterNative, 17(3), 357–367.

Derrida, J. (1976). Of grammatology (G. C. Spivak, Trans.). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Federal Court of Australia. (2014). Native Title Consent Determination, Butchulla People #2, De Satge on behalf of the Butchulla People #2 v State of Queensland [2014] FCA 1132, File number QUD 287 of 2009, The Honourable Justice Collier, Fraser Island, Queensland, Friday 24 October 2014.

Foley, F. (2020). Biting the clouds: A Badtjala perspective on the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act, 1897. University of Queensland Press.

Foley, F. (2021). Bogimbah Creek Mission: The first Aboriginal experiment. Pirri Productions.

Foley, S. (1996). Badtjala–English / English–Badtjala word list. Wondunna Aboriginal Corporation.

Garden, J. G., McAlpine, C. A., Possingham, H. P., & Jones, D. N. (2007). Using multiple survey methods to detect terrestrial birds and mammals: What are the most successful and cost-efficient combinations? Wildlife Research, 34, 218–227.

Harrison, N., Bodkin, F., Bodkin-Andrews, G., & Mackinlay, E. (2017). Sensational pedagogies: Learning to be affected by Country. Curriculum Inquiry, 47(5), 504–519.

Harrison, N., & Skrebneva, I. (2020). Country as pedagogical: Enacting an Australian foundation for culturally responsive pedagogy. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 52, 15–26.

Harvey, A., & Russell-Mundine, G. (2019). Decolonising the curriculum: Using graduate qualities to embed Indigenous knowledges at the academic cultural interface. Teaching in Higher Education, 24, 789–808.

Hird, C., David-Chavez, D. M., Gion, S. S., & van Uitregt, V. (2023). Moving beyond ontological (worldview) supremacy: Indigenous insights and a recovery guide for settler-colonial scientists. Journal of Experimental Biology, 226(12), Article jeb245302. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.245302

International Labour Organisation. (1989, June 7). Proceedings of the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989. General Conference of the International Labour Organisation, Convention C169, Geneva, Switzerland.

Khedkar, P. D., & Nair, P. (2016). Transformative pedagogy: A paradigm shift in higher education. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research and Practice, India, 4, 332–337.

Lincoln, G., Austin, B. J., Dobbs, R. J., Mathews, D., Oades, D., Wiggan, A., Bayley, S., Edgar, J., King, T., George, K., Mansfield, J., Melbourne, J., & Vigilante, T., with the Balanggarra, Bardi Jawi, Dambimangari, Karajarri, Nyul Nyul, Wunambal Gaambera & Yawuru Traditional Owners. (2017). Collaborative science on Kimberley saltwater Country – A guide for researchers (version 17.03). Kimberley Land Council for the Kimberley Indigenous Saltwater Science Project, Western Australian Marine Science Institute.

Martinez, D. J., Cannon, C. E. B., McInturff, A., Alagona, P. S., & Pellow, D. N. (2023). Back to the future: Indigenous relationality, kincentricity and the North American model of wildlife management. Environmental Science & Policy, 140, 202–207.

Millner, N. (2021). Unsettling feelings in the classroom: Scaffolding pedagogies of discomfort as part of decolonising human geography in higher education. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 47(6), 805–824.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2017). Relationality: A key presupposition of an Indigenous social research paradigm. In C. Andersen & J. O’Brien (Eds.), Sources and methods in Indigenous studies (pp. 69–77). Routledge.

Mudaly, R., & Ismail, R. (2013). Teacher learning through tapping into Indigenous knowledge systems in the science classroom. Alternation, 20, 178–202.

Murray, G., & Campton, S. (2023). Reducing racism in education: Embedding Indigenous perspectives in curriculum. Australian Educational Researcher, 51(5), 1771–1790.

Nakata, M. (2007). The cultural interface. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 36, 7–14.

Nakata, M. (2010). The cultural interface of Islander and scientific knowledge. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 39, 53–57.

Nakata, M., Hamacher, D., Warren, J., Byrne, A., Pagnucco, M., Harley, R., Venugopal, S., Thorpe, K., Neville, R., & Bolt, R. (2014). Using modern technologies to capture and share Indigenous astronomical knowledge. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 45(2), 101–110.

Reeves, W. (Moonie Jarl). (1964). The legends of Moonie Jarl. Jacaranda Press.

Rossiter, M. (2002). Narrative and stories in adult teaching and learning. ERIC Digest, ED473147. ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult Career and Vocational Education.

Salisbury, S. W., Romilio, A., Herne, M. C., Tucker, R. T., & Nair, J. P. (2017). The dinosaurian ichnofauna of the Lower Cretaceous (Valanginian-Barremian) Broome Sandstone of the Walmadany area (James Price Point), Dampier Peninsula, Western Australia. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 16, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 36(supp to 6), i–viii & 152.

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2011). Nagoya protocol on access to genetic resources and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Serafini, F. (2000). Three paradigms of assessment: Measurement, procedure and inquiry. The Reading Teacher, 54(4), 384–393.

Simpson, L. B. (2017). Land as pedagogy. In L. B. Simpson (Ed.), As we have always done: Indigenous freedom through radical resistance (pp. 145–174). University of Minnesota Press.

Sobel, D. (2017). Place-based education: Connecting classrooms and communities. Orion Magazine.

Stephens, S. (2000). Handbook for culturally responsive science curriculum. Alaska Native Knowledge Network.

Tasker, E. N., & Dickman, C. R. (2001). A review of Elliot trapping methods for small mammals in Australia. Australian Mammalogy, 23, 77–87.

Thompson, P., & Marsh, H. (2022). Centering equity: Trauma-informed principles and feminist practice. In P. Thompson & J. Carello (Eds.), Trauma-informed pedagogies (pp. 15–33). Palgrave Macmillan.

Tomlinson, M. (2014). Student perceptions of themselves as “consumers” of higher education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(4), 450–467.

Wilson, S., & Schellhammer, B. (2021). Indigegogy: An invitation to learning in a relational way. WBG Academic.

World Intellectual Property Organization. (2024, May 13–24). WIPO treaty on intellectual property, genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge. Diplomatic Conference to Conclude an International Legal Instrument Relating to Intellectual Property, Genetic Resources and Traditional Knowledge Associated with Genetic Resources, Geneva, Switzerland.

Yunkaporta, T., (2023). Aboriginal pedagogy: Integrity in academic and cultural practice. Holistic Education Review, 3(1), 1–6.

Yunkaporta, T., & McGinty, S. (2009). Reclaiming Aboriginal knowledge at the cultural interface. Australian Educational Researcher, 36(2), 55–72.