2 Developing an Indigenous language revitalisation program

Desmond Crump and Samantha Disbray

School of Languages and Cultures

Introduction

With the Decade of Indigenous Languages (2022–2032) underway, community-led Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages revival and revitalisation projects can be found across Queensland and nationally. The need for training and accreditation to upskill and professionalise Indigenous practitioners and teachers has long been identified to achieve community goals for languages and employment (First Languages Australia, 2021). In response, the new Graduate Certificate in Indigenous Language Revitalisation (GCILR) program was developed by an Indigenous-led team at The University of Queensland (UQ), and the first student intake commenced in Semester 2, 2024. The program is targeted at Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and provides access to specialist learning and accreditation. It opens opportunities to network and to become language specialists in fields such as language and cultural revival, education, archival research and data rights, the arts, land management, and governance.

In addition to creating a new program, this work brings a new discipline of Indigenous Language Revitalisation (ILR) into the University (School of Languages and Cultures, n.d.-b) – the first ILR program in an Australian university. Reclaiming Indigenous control over languages is at the heart of ILR and is an inherently decolonising process. Both reclamation and decolonisation as characterised by First Nations scholars (such as Charity Hudley et al., 2020; Leonard, 2017; Woods, 2023) have driven the UQ ILR program design processes. Created by and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, with Indigenous governance, languages and experience centred, the outcome is a “born-Indigenised” curriculum.

Positioning of the authors

Desmond Crump is a Gamilaroi language teacher and researcher in the role of Industry Fellow (Indigenous Languages) working on Yuggera and Turrbal Country at UQ. Samantha Disbray is a non-Indigenous linguist, working on Yuggera and Turrbal Country at UQ, with an extensive background in community language revival and teaching.

Indigenous language revitalisation

ILR has its origins in the work of First Nations practitioners in local contexts across the globe to reclaim, revive, and maintain language and cultural practices. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s networks of First Nations practitioners and a growing community of scholars have articulated practice and contributed critique and theory to the field – in Australia, with the founding work of Jeanie Bell (2003; 2010; 2013) and, more recently, by Lesley Woods (2023), and a rich international canon (including De Korne & Leonard, 2017; Leonard, 2017; McCarty et al., 2018; McIvor, 2020). This has been accompanied by growing support from university partners, among them notably the University of Arizona (Cantoni, 1996); the University of Hawai‘i (Kawaiʻaeʻa et al., 2007); the University of Victoria, Canada (Czaykowska-Higgins et al., 2017); and, in Australia, Batchelor Institute (see Ngoonjook, batchelorpress.com/catalog/ngoonjook ) and now, UQ.

ILR is a multidisciplinary set of approaches and practices, which bring together community building, activism, decolonising theory and practice, research, linguistic (re)analysis, language teaching and learning, resource development and sharing, digital technologies, and project management. Miyami linguist and language activist Wesley Leonard (2017) critiques a narrow focus on linguistic methods, speaker numbers and language proficiency in defining language revitalisation. He foregrounds reclamation, which “begins with community histories and contemporary needs … determined by community agents and produced in a way that integrates ‘non-linguistic’ factors” (Leonard, 2017, pp. 19–20; also, McCarty, 2021, p. 927). Beginning with local histories, needs, power and leadership, ILR recognises and works through the underlying causes and outcomes of language dispossession and shift, and so decolonising scholarship and practice are central. For nehinaw (Swampy Cree) and Scottish-Canadian academic Onowa McIvor (2020), a decolonising approach “brings a social justice aim to one’s academic and personal work, and, in relation to ILR, it contributes to the revival of Indigenous languages as part of a larger movement restoring the value that all citizens can see in Indigenous ways of knowing” (p. 79). Decolonising linguistics more broadly is fast emerging among First Nations and non-Indigenous scholars and practitioners, both internationally (Charity Hudley et al., 2020) and in Australia (Gaby & Woods, 2020; Indigenous Alliance for Linguistic Research, n.d.).

On the Dharug Bayala website page “Decolonising Dharug Dhalang” (Dharug language) (Bayala, 2021), the creators describe the importance of Dharug researchers “diving into historical sources to reclaim and revitalise their language” (para. 1) for the first time and write:

This approach represents a significant shift from traditional methodologies, where non-Indigenous academics often led linguistic research and documentation. By focusing on Dharug’s voices and perspectives, the project not only restores control of the linguistic narrative to the Dharug people but also challenges the historical power imbalances established by colonial practices. This effort aligns with broader decolonial movements that affirm Indigenous autonomy over cultural and intellectual heritage, ensuring that the Dharug community can accurately and authentically revive their ancestral language. (para. 1)

The UQ ILR team participates actively in this movement and are guided by its approaches. Voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language practitioners and experts guided the co-design, as well as being front and centre of curriculum and pedagogy in the ILR program, a key initiative in the UQ School of Languages and Cultures (SLC).

The School has a long history of training and employing non-Indigenous linguists. Many have built successful careers through their research and work with Indigenous languages and communities, Samantha Disbray included. At the same time, the staff in the School and many in the field of linguistics in Australia increasingly recognise the discipline’s colonialist drive and outcomes, and are committed to more ethical and mutually beneficial practices (Woods, 2023, pp. 7–8). Nevertheless, the number of Indigenous linguists and academics remains unacceptably low. The GCILR seeks to address this by providing the learning, research and networking opportunities for students to carry out the work they want to, with the tools they need, and to provide pathways to further research.

Indigenising the curriculum and ILR

While noting the delineation between decolonisation and Indigenisation (Guerzoni, 2020, p. 9), it is unsurprising to see alignment between the goals of Indigenising the curriculum and ILR, with the focus of ILR on centring Indigenous voices, histories, perspectives and leadership in the reclamation of Indigenous languages and practices.

Throughout this chapter, we bring to the fore synergies between the process to design the UQ ILR program and the seven Indigenising Curriculum Design Principles articulated by the UQ Indigenising Curriculum Working Party (2022, p. 12). The seven principles are Country, Relationships, Respect, Cultural Capability, Reciprocity, Truth and Benefits (Bunda, 2022, pp. 13–19). Country is central to relationships and embodies diversity across First Nations. Relationships recognises the need for partnership, protocols and remuneration to knowledge holders. Proceeding with Respect involves acknowledging Indigenous peoples as knowledge holders and sustains relationships, while valuing and sharing Indigenous knowledges, practices and perspectives. Cultural Capability is expressed through understandings and adherence to protocols and respectful engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, knowledges and perspectives. Reciprocity is built on mutually agreed relationships. Truth and truth-telling centres the Indigenous voice in curriculum and the inclusion of literature by Indigenous authors and Indigenous perspectives and knowledges. The contribution of these knowledges to a discipline and curriculum represents one part of Benefits, the empowerment of Indigenous students another. We return to these at the end of the chapter. But now we begin at the beginning – creating an Indigenous-led co-design process.

Co-designing the UQ Indigenous Language Revitalisation program

An Indigenous Project Steering Group (PSG) was formed to establish Indigenous governance over every aspect of the work at the outset of the project. Members were recruited though an expression of interest process, advertised through language community and industry networks. In the first meeting in March 2022, the PSG of initially 14 members developed its terms of reference, with a co-chair structure with non-staff and staff members, representation from diverse Nations, gender balance, and a decision-making mandate over the process and outcomes for ILR at UQ. Funding to meet six times per year with travel and payment to non-staff members was provided by the SLC. The membership has changed over time but remains made up of language professionals and language knowledge holders, who have been actively involved in Indigenous language work and policy, from industry and community, and an equal number of UQ Indigenous staff members. The expertise of the PSG community members was crucial at each development stage. While leadership at the University, Faculty and School levels sought to clear barriers to this work, a practical challenge was ensuring timely payment to non-staff members. This matter was largely resolved once systems were put into place.

The foundational aim of the PSG was to develop a teaching and learning program in partnership with the University to meet community goals for ILR. Though control of the design of a learning program is rarely put into the hands of a steering group comprising non-UQ staff, the knowledge and experience of all members was respected and drove the program design, enacting the Indigenising curriculum principles of Relationships, Respect, Reciprocity, Benefits and Cultural Capability (Bunda, 2022). The PSG gradually built strong relationships with staff across the University, to advocate for and build support for the emergent program. This provided a solid basis for Indigenising the process, development of the program and the curriculum.

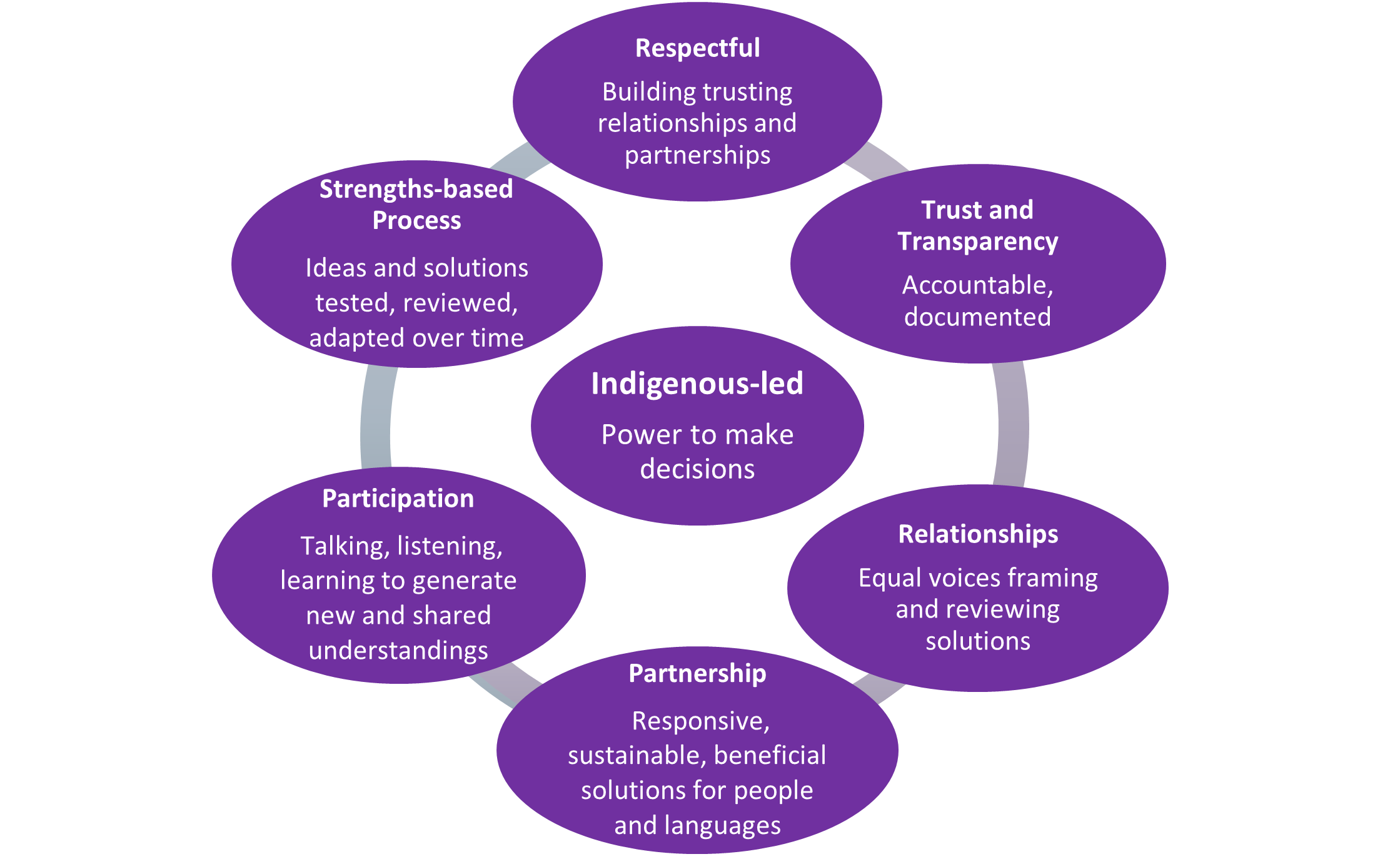

In the fifth meeting in the first year of the project, PSG members reflected on the ways the group worked together and articulated these as co-design principles.

Tip

Tip

Adequate time and resourcing, including funds and efficient procedures for making payment, are needed for successful collaboration between Indigenous specialists and university staff.

Tip

Tip

Non-Indigenous staff need elevated levels of cultural competency to support and amplify Indigenous community members and staff. This allows a group to work together to develop the processes and protocols to guide the journey ahead, as they build the foundations for shared expectations, trust and genuine joint decision-making.

In the GCILR development process, evolving cultural humility among non-Indigenous personnel within the program is acknowledged. Cultural humility can be defined as “a lifelong process of self-reflection, self-critique, and commitment to understanding and respecting different points of view” (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998). It involves engaging with others humbly, authentically and from a place of learning. The nature of the program being co-designed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people extends beyond the simple catchcry of “nothing for us without us”. There is a clear and present need to ensure non-Indigenous staff have a deep level of understanding of the contexts and associated impacts on Indigenous languages revitalisation. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have an important role to enhance cultural competency of their colleagues to bring them along on the journey and create productive allies.

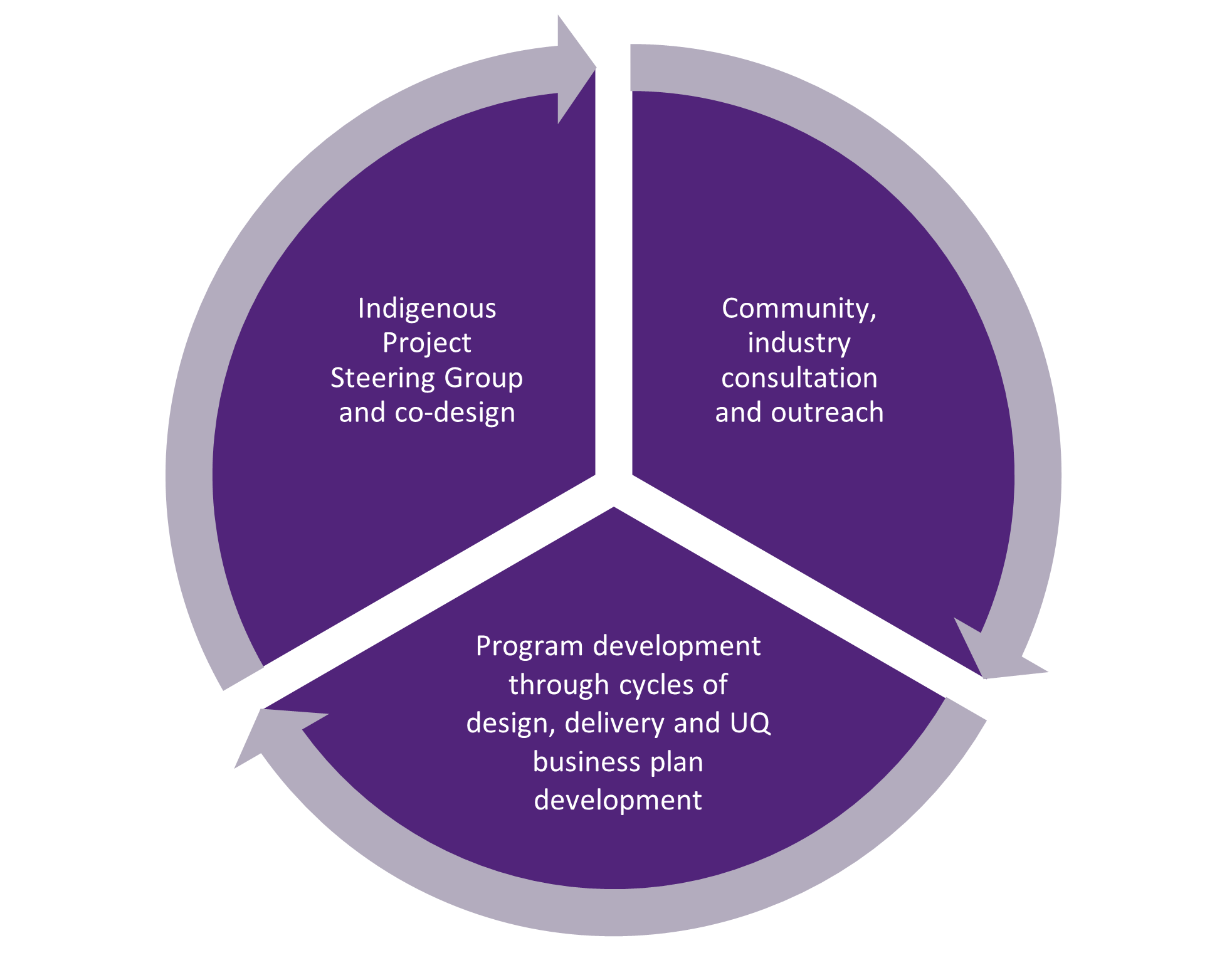

With the PSG and co-design principles in place, a two-year process of listening, thinking, designing, advocating, trialling, reviewing, documenting and discussing proceeded, depicted in Figure 2. The process featured:

- listening to experts from community language networks

- consulting and advocating with government and industry bodies about industry needs, accreditation and recognition of language skills

- building relationships and understanding with key staff and sections of the University

- identifying program level, content, good delivery modes and funding for a sustainable future

- developing and piloting shorter form credentials (SFC) with PSG community members

- developing and compiling a business plan in collaboration with the PSG and working across UQ units to propose the Graduate Certificate program.

Figure 2. Co-design process

The “listening” phase enacted Indigenous ways of doing (Martin / Mirraboopa, 2003) by building respectfully on and extending the relationships and networks of the PSG members to share and seek information and explore and create new possibilities together. The community PSG members, including the UQ ILR team Industry Fellows (Indigenous Languages) Des Crump and Robert McLellan, and non-Indigenous colleague Samantha Disbray, all have established relationships to people in communities and community organisations, such as the national peak body First Languages Australia; language centres; industry, including schools and education departments; and the GLAM sector (galleries, libraries, archives and museums). This wider network created a circle of “critical friends” who could provide advice and input on specialist topics.

Tip

Tip

Clear processes and protocols ensure all stakeholders are genuinely active in consultations, decision-making, and documentation and information shared effectively. This allows collaborative nets to be cast wider, expanding understandings and building a stronger and more inclusive network.

Undertaking deep conversations over time in the ILR program development built strong alignment to current demand, policy and developments for languages as broader networks came into the dialogue. The ILR team documented all consultation work, reported back to the PSG, and discussed and sought guidance and instruction in 12 meetings in 2022 and 2023. This process was documented in the business case eventually prepared for the Graduate Certificate. However, before reaching this stage, the team began a process of “delivering while developing”, adhering to the process-driven, outcome-focused and iterative co-design principles.

Delivering while developing – building relationships, trust and understanding

Already by the second meeting early in 2022, the PSG worked on and approved the proposal to create and offer two SFC modules: Building your Language Revitalisation Network (LING7011) and Being an Adult Language Learner in a Language Revitalisation Context (LING7012). Participants were recruited and the first language revitalisation studies offering was in a three-day intensive in July 2022. Five-day summer and winter intensives in January and July 2023 expanded to a four-module offering, adding Language Research in Archives (LING7013), delivered in partnership with the UQ Fryer Library Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander team, and Language Descriptions (LING7014).

Locating a community-responsive program in a university setting requires cultural capability and the willingness to use empowering pedagogies. This is elemental for breaking down barriers and establishing trust with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and communities. For many of the participants in the intensives, this was their first experience in a university context and, as such, they were apprehensive; hence the great need to build relationships based on trust and respect. Prior relationships between UQ staff and community language specialists assisted this. The presence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff from UQ also had a positive impact on the program and its delivery; Indigenous linguists and researchers as well as the UQ Library Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services and Collections team and Fryer Library staff made participants not only welcomed, but proud to see other Indigenous faces in the mainstream setting of UQ. The course content was also carefully developed to be process-driven and student-led outcome-focused, with renewable tasks and assessments (Clinton-Lisell & Gwozdz, 2023) designed for students to develop and produce a language/community specific resource. This allows participants to take charge of their own learning and language revitalisation efforts, an approach further fine-tuned in the Graduate Certificate program.

Piloting SFCs in small-scale workshops while developing a larger program allowed the UQ team to build relationships within the University, and outside, with students, communities and organisations. The team deepened their understanding of the participants’ needs in revitalising their languages, delivery models and levels of demand, while building a profile and basis for trust in UQ among communities. The SFCs were an important vehicle in the co-design process. They could be relatively quickly developed and approved through UQ’s Academic Board, providing a nimble way to design while delivering.

Community-centred pedagogies

Community-centred, empowering pedagogies were utilised in the SFC intensives. Social learning, reciprocal learning through small groups of like-minded individuals, was trialled and refined through SFC course offerings. The ILR teaching team respects that each student brings their own set of skills and knowledge into the program and through the intensive. Everyone is a teacher as well as learner. Indeed, the team acknowledges the knowledge in the room in all learning activities. Most students are actively involved in language revival, including teaching in their own communities, and they are often the most expert people on their own languages. Their knowledge was actively incorporated in the instruction, for instance, in language examples in linguistic terminology and method sessions, and in participant-led sessions of hands-on teaching and learning demonstrations.

The three intensive programs held in 2022–23 attracted community language activists and professionals from across Queensland, and from New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. Such a broad range of students enabled quality feedback on the course and its application to Australia-wide language contexts. All course, accommodation and catering costs were covered by the SLC, recognising the valuable contribution the participants made to the ILR program development and enacting reciprocity. Feedback from the participants was valuable and overwhelmingly positive. Workshop days always began with a check in, in a yarning circle format. The instructor team worked to create a safe space for compassionate and open-ended talk. This was just one way that the team learned enormously from the participants in the summer and winter programs, learnings that were incorporated with gratitude into the Graduate Certificate program.

Graduate Certificate in Indigenous Language Revitalisation: An Indigenised curriculum with empowered pedagogies

The GCILR was offered for the first time in August 2024. There are several pathways to meet the program entry requirements to meet the diverse needs and profiles of language specialists in the community (School of Languages and Cultures, n.d.-a). The delivery mode involves a series of online classes before the one-week on-campus intensive and a series of online post-intensive sessions. Students who are not Brisbane residents travel and are accommodated for the intensive week through the Away from Base funding program, managed by Centrelink. The SLC funds a part-time administration position to coordinate this.

The program is offered over one year, part-time, with four two-unit courses:

- Introduction to Indigenous Language Revitalisation (AUIL7200), in which the four SFC modules are bundled

- Indigenous Languages: Understanding Language Description for Access and Use (AUIL7201)

- Learning, Using and Sharing Indigenous Languages (AUIL7202)

- Building Strong Language Communities (AUIL7203), a capstone course with a final extended own-language project.

Four skill sets and concepts were identified in the co-design process as central to all courses and are integrated as empowering pedagogy and/or into assessment for each. These are:

- truth-telling, culture and healing

- active language learning

- using technology for language revitalisation

- own-language resource creation.

Truth-telling and healing are incorporated into all courses by investigating past and present policies and practices that repress languages and speakers, critically reviewing language documentation practices, and celebrating the work of the students and their communities in reclaiming their cultural and language knowledge. To foreground culture and truth, program instructors ensure that language is not decontextualised from speakers, communities and histories. One of the ways we achieve this is through course readings and delivery by First Nations people. The discussions that flow bring students’ sharing and reflection on their own histories and language situations into the knowledge shared in the room. In designing the course material, Indigenous authors and producers and their accounts of language revitalisation are prioritised, giving students opportunities to connect their stories with local and global experiences and practices.

Each cohort represents diverse Nations and languages. To provide a language-general program with language-specific learning, the content, tasks and assessments in each course are tailored and differentiated to support students to undertake practical and effective own-language learning. This element of the program recognises and supports the unique knowledge and experiences each student brings to the program and that they seek to grow.

Technological tools abound in language revitalisation work – in archival searching and storage, annotation, language transcription, resource creation, use and dissemination. Each course introduces technologies relevant to its content and ensures hands-on practice. For instance, in the Introduction AUIL7200 course, students undertake archival research and then learn to create and use an Excel spreadsheet with drop-down menus to create a catalogue and workflow document of resources important for researching and reigniting their language. The catalogue is an assessment item as well as an own-language resource for documenting and planning access and further work on materials, published or unpublished, and so supports project-management skills development.

The catalogue is an example of a renewable task, designed to have value for the student and the community they choose to share it with (Clinton-Lisell & Gwozdz, 2023). All GCILR assessments are designed to be renewable, with students having control over the content, and often the format, to best suit the needs they have for a resource to meet the needs of their own real-world context. Other examples include creating resources that explain a feature of a language or units of work for sharing and learning. This pedagogical approach embeds the urgency of language revitalisation and the responsibility the students have set for themselves as language champions. There is no time to waste on assessment for assessment’s sake.

Real-world connection is also activated by the presence of Indigenous instructors and guest speakers in the program, and in the course materials, which are overwhelming authored by Indigenous scholars and practitioners. Industry Fellow Des Crump leads intensive sessions on archival research, teaching and learning, while Robert McLellan delivers guest sessions on areas of his expertise such as Indigenous Data Sovereignty. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander team in the UQ Library collaborate with the ILR team to deliver an archival research experience and content on Indigenising metadata and Indigenous cultural and intellectual property in the Introduction AUIL7200 course. Indigenous linguist Gari Tudor-Smith (Gureng-Gureng/Gangulu) and languages education expert Tahlia O’Brien (Guugu Yalanji) lead the teaching in AUIL7201 and AUIL7202 respectively. Gari is one of the authors of Bina: First Nations Languages, Old and New, alongside Gamilaraay linguist Paul Williams and non-Indigenous linguist Felicity Meakins (Tudor-Smith et al., 2024). Bina is required reading in three courses. Guest speakers, such as Dharug language revitalisation leader Jasmine Seymour, are regularly invited to present. These Indigenous experts and language champions provide up-to-date knowledge and are crucial role models as First Nations language specialists. This approach is adopted to empower students as practitioners, community members and scholars, as the students take part in new knowledge creation of their own through their shared learning experiences with the instructors and with other students and through their own resource creation. The ILR team and students speak in frank dialogue about this approach to pedagogy and the assessment strategy, highlighting that the University and its staff are not the holders of the knowledge, but act as facilitators to support the development of new knowledge by and for the students and their language communities.

Tip

Tip

Explore empowering pedagogies to elevate Indigenous knowledges and people. Explore approaches in the classroom, which draw on the knowledge and experience of the students in the room, through sharing, demonstrations and storytelling. Bring Indigenous expertise from outside into the room, as lecturers, guest speakers and authors in written and audio/visual text are another important means.

Wrapping up and going forward

This chapter has detailed the partnerships and process to develop the GCILR at UQ, highlighting principles that have guided the collaborative co-design of the program. It has shown that building and valuing relationships both in and outside the University have been central (Bunda & Barney, 2024). Outside UQ, this has been realised by respecting and responding to First Nations peoples and their knowledges in very concrete ways – through PSG leadership, co-design, process documentation, and governance; wide-ranging community and industry consultation; and incremental program piloting with participants in the SFC intensives – with reciprocity firmly motivating our approach.

The ILR team has worked to build relationships and cultural competency with colleagues across the University throughout the process – in the development of courses, assessment, the business plan, entry requirement provisions, recruitment and support mechanisms – to ensure that the GCILR is grounded in cultural safety for the students, instructors, guest speakers and PSG community members. Our efforts were met consistently with an openness and willingness to learn, support and adapt to achieve the best outcomes for the program from UQ colleagues across the University: the SLC; the Faculty of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences; the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit; the Office of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement); Planning and Business Intelligence; UQ legal; and the Standing Committee of the Academic Board. With GCILR teaching underway, non-Indigenous SLC staff have been generous and enthusiastic to understand how they can best share their expertise with the ILR students, providing guest talks and student consultations. This has added a further richness to the program, built the cultural competency of SLC staff and strengthened the network of support for the students with positive reciprocal benefits.

The GCILR is a course for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students designed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Guerzoni (2020) states that “curricula Indigenisation is also more than the inclusion of cultural knowledge or experiences; it is a scholarly endeavour framed around Indigenous scholarship” (4). The GCIRL reflects this notion and represents a new way of doing things for the University. The ILR team was recognised for its contribution to reconciliation with a 2024 UQ Award for Excellence. With the first offering now complete, the ILR team will work with a renewed PSG to improve the program for future cohorts. We aim to realise its potential as a pathway into community-driven and output-focused Higher Degree by Research study for program graduates to continue their journeys in rebuilding languages and language communities.

Reflection questions

- How do you establish trust with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities?

- What does authentic co-design look like?

- How would the steps towards Indigenising the curriculum be similar and different in your context?

- What is the network you can draw on to support this?

Terminology

Throughout the chapter, the terms “First Nations”, “Indigenous” and “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander” are used. These terms can be interpreted differently in different contexts. However, in this context they all refer to the first peoples of Australia, acknowledging the diversity across and within Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander communities. “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages” refers to traditional languages as well as contact languages, including Aboriginal Englishes and Creole languages.

References

Bayala. (2021). Historical sources of Dharug language: Decolonising Dharug dhalang. https://bayala.net.au/research-and-publications/historical/william-dawes-notebooks/

Bell, J. (2003). Australian Indigenous languages. In M. Grossman (Ed.), Blacklines: Contemporary critical writing by Indigenous Australians (pp. 145–154). Melbourne University Press.

Bell, J. (2010). Language and linguistic knowledge: A cultural treasure. Ngoonjook, 84–96.

Bell, J. (2013). Language attitudes and language revival/survival. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 34(4), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.794812

Bunda, T. (2022). Indigenising curriculum: Consultation green paper. Office of the Pro Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement) and Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation. The University of Queensland.

Bunda, T., & Barney, K. (Hosts). (2024, March 1). Relationships: Des Crump & Samantha Disbray [Audio podcast episode]. In Indigenising curriculum in practice. The University of Queensland. https://indigenisingcurriculum.podbean.com/e/relationships-des-crump-and-samantha-disbray/

Cantoni, G. (Ed.). (1996). Stabilizing indigenous languages (1st ed.). Northern Arizona University.

Charity Hudley, A., Mallinson, C., & Bucholtz, M. (2020). Toward racial justice in linguistics: Interdisciplinary insights into theorizing race in the discipline and diversifying the profession. Language, 96(4), 200–235. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0rk3v400

Clinton-Lisell, V., & Gwozdz, L. (2023). Understanding student experiences of renewable and traditional assignments. College Teaching, 71(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2023.2179591

Czaykowska-Higgins, E., Burton, S., McIvor, O., & Marinakis, A. (2017). Supporting Indigenous language revitalisation through collaborative post-secondary proficiency-building curriculum. Language Documentation and Description, 14, 136–159.

De Korne, H., & Leonard, W. (2017). Reclaiming languages: Contesting and decolonising “language endangerment” from the ground up. Language Documentation and Description, 14, 5–14. https://doi.org/10.25894/ldd145

First Languages Australia. (2021). Report on best-practice implementation of the framework for Aboriginal languages and Torres Strait Islander languages.

Gaby, A., & Woods, L. (2020). Toward linguistic justice for Indigenous people: A response to Charity Hudley, Mallinson and Bucholtz. Language, 96(4), 268–280. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2020.0078

Guerzoni, M. A. (2020). Indigenising the curriculum: Context, concepts and case studies. Office of the Pro Vice-Chancellor, Aboriginal Leadership, University of Tasmania. Retrieved October 1, 2024, from https://www.utas.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/1452520/Indigenising-the-Curriculum-Context,-Concepts-and-Case-Studies.pdf

Indigenous Alliance for Linguistic Research. (n.d.). Spinning a better yarn: Decolonising linguistics. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCAPSm4ftmOW7FfxhvMN5OLA

Kawaiʻaeʻa, K. K. C., Housman, A. K., & Alencastre, M. (2007). Pūʻā i ka ʻŌlelo, Ola ka ʻOhana: Three generations of Hawaiian language revitalization. Hūlili: Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Wellbeing, 4(1), 183–237. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED523186

Leonard, W. (2017). Producing language reclamation by decolonising “language”. Language Documentation and Description, 14, 15–36. https://doi.org/10.25894/ldd146

Martin, K., / Mirraboopa, B. (2003). Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and Indigenist re‐search. Journal of Australian Studies, 27(76), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050309387838

McCarty, T. L. (2021). The holistic benefits of education for Indigenous language revitalisation and reclamation (ELR2). Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 42(10), 927–940.

McCarty, T. L., Nicholas, S., Chew, K., Diaz, N., Leonard, W., & L. White. (2018). Hear our languages, hear our voices: Storywork as theory and praxis in Indigenous-language reclamation. Daedalus, 147(2), 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00499

McIvor O. (2020). Indigenous language revitalization and applied linguistics: Parallel histories, shared futures? Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 40,78–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190520000094

School of Languages and Cultures. (n.d.-a). Graduate Certificate in Indigenous Language Revitalisation. The University of Queensland. https://languages-cultures.uq.edu.au/Indigenous-language-revitalisation/grad_cert

School of Languages and Cultures. (n.d.-b). Indigenous Language Revitalisation program. The University of Queensland. https://languages-cultures.uq.edu.au/indigenous-language-revitalisation

Tervalon, M., & Murray-García, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

Tudor-Smith, G., Williams, P., & Meakins, F. (2024). Bina: First Nations languages, old and new (1st ed.). Black Inc.

Woods, L. (2023). Something’s gotta change. Redefining collaborative linguistic research. ANU Press.