17 UQ Business School Indigenising curriculum with technology

Ree Jordan; Micheal Axelsen; Sabine Matook; Mark Bremhorst; Andrew Burton-Jones; Victor Callan; Louise Ferris; Stan Karanasios; Aliisa Mylonas; Richard O’Quinn; and Ashil Ranpara

UQ Business School

Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation

Faculty of Business, Economics and Law

Introduction

Our teaching and learning context: UQ Business School

Teaching and learning at higher education institutions shape the values, knowledge and culture of future organisation leaders, such as managers, politicians and business owners. Business schools are at the forefront of this, as they aim to educate students on all topics of “doing” business (such as organisational behaviour and ethical practices, marketing, management, and accounting and finance). The topics taught aim to inform and educate current and future leaders on sustainable, ethical and moral practices, thereby playing a key role in shaping a future that ensures marginalised voices and perspectives are heard and valued in mainstream society. Through embedding Indigenous knowledges, values and perspectives in course curricula, business schools demonstrate the importance and relevance of Indigenous content in contemporary Australian business practices (adapted from Gainsford & Evans, 2017).

Like other parts of The University of Queensland (UQ), the UQ Business School embraces the need to Indigenise curricula across all programs and course offerings, which is particularly important given the 2023 data revealing that this School alone accounts for approximately 20% of total enrolments at the University. Foundational to these educational efforts is technology as an enabler to create, transform and apply knowledge. In this chapter, we explore how teachers from different UQ Business School disciplines, together with learning designers and educational staff, approached Indigenising curriculum using technology. We provide teaching tips based on our experiences, offer questions of reflection and, with the advent of artificial intelligence (AI), foreshadow future paths in the Indigenising curriculum–technology connection in higher education classrooms.

Our location: Who we are and where we come from

This chapter was developed through a collaboration of 11 authors from rich and diverse cultural backgrounds whose collective insights present the role of technology as a learning enabler for Indigenous knowledge teaching and learning. We briefly introduce and position ourselves:

- Ree Jordan is of Aboriginal descent with family ties to the Barunggam people in the Western Downs region of Queensland, on the red soils south and west of the Great Dividing Range. She now works on the traditional lands of the Turrbal and Jagera peoples.

- Micheal Axelsen grew up in Ipswich, Queensland, which is located on Yagara Country known traditionally in the Yugara/Yagara language as Tulmur. He continues to live and work on the lands of the Turrbal and Jagera peoples.

- Sabine Matook is a proud German who was born on Saxonian land in Dresden, Germany. She now works and lives in Australia on Turrbal and Jagera Country.

- Mark Bremhorst is a Queenslander, born and raised in Brisbane. He grew up on Turrbal Country where he still lives today.

- Andrew Burton-Jones grew up in Moggill, a suburb of Brisbane. The word Moggill comes from the Yuggera word for water dragon, although he was not aware of this growing up.

- Victor Callan is a proud Queenslander, working for 40 years on Turrbal and Jagera Country, but born and raised on the beautiful South Coast of New South Wales, Dharawal Country.

- Louise Ferris (formerly Crowe) is a Wangaaypuwan Ngiyampaa and Wiradjuri woman. Her ancestral Country is amongst the Bunggan (Bogan) and Wambuul (Macquarie) Rivers of central and western New South Wales. Now, she is residing on Ningy Ningy Country (Redcliffe Peninsula).

- Stan Karanasios grew up in Cheltenham on the traditional lands of the Bunurong people of the Kulin Nation. He now lives and works on Turrbal and Jagera Country at St Lucia in Queensland.

- Aliisa Mylonas is a first generation Australian who feels very fortunate that her two adventuresome immigrant parents, from different countries and cultures, embraced Meanjin (Brisbane) as their home.

- Richard O’Quinn was born in the Appalachian region of Virginia, USA, on the traditional lands of the ancient Chisca and later Cherokee peoples. He currently lives and works in Australia on the traditional lands of the Jagera and Turrbal peoples.

- Ashil Ranpara lives and works on lands where the Turrbal, Yagera and Yugumbeh peoples have been the Custodians for millennia.

Indigenising curriculum: What informed our approach

Each of the authors responded early to the call to Indigenise curriculum. While they employed various methods, a common element was that each approach was significantly enhanced through the use of digital technology. This emphasises the important role that digital technology, and indeed information systems (IS) more broadly, play in this undertaking. In looking to Indigenise our courses through engagement with technology, we had to first understand what is meant by Indigenising curriculum. According to Universities Australia (2022), it refers to the respectful and meaningful incorporation of Indigenous knowledges and perspectives into university course curricula. We acknowledge that engagement can be at the level of incorporating Indigenous ways of knowing (epistemologies), ways of being (ontologies) and ways of doing (axiologies) (Wilson, 2008). It was also important to us to recognise that Indigenising curriculum refers to validating Indigenous pedagogical practices as appropriate, alternative ways of teaching and learning that have withstood the test of time, allowing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures to thrive over thousands of years.

Central to our approach is understanding that traditional Indigenous knowledges and practices stem from facts, norms, values, beliefs and practices specific to local systems (Weiss et al., 2013). These are shared through intergenerational story telling. Indigenising the curriculum, therefore, provides an opportunity to recognise the validity of alternative ways of knowing, being and doing that are relevant to course themes, although they may stand in contrast to dominant Western perspectives. Through embedding Indigenous knowledges and perspectives into programs, universities commit to establishing pathways for students to recognise the value and benefits of striving for the advancement of Indigenous peoples (Universities Australia, 2022).

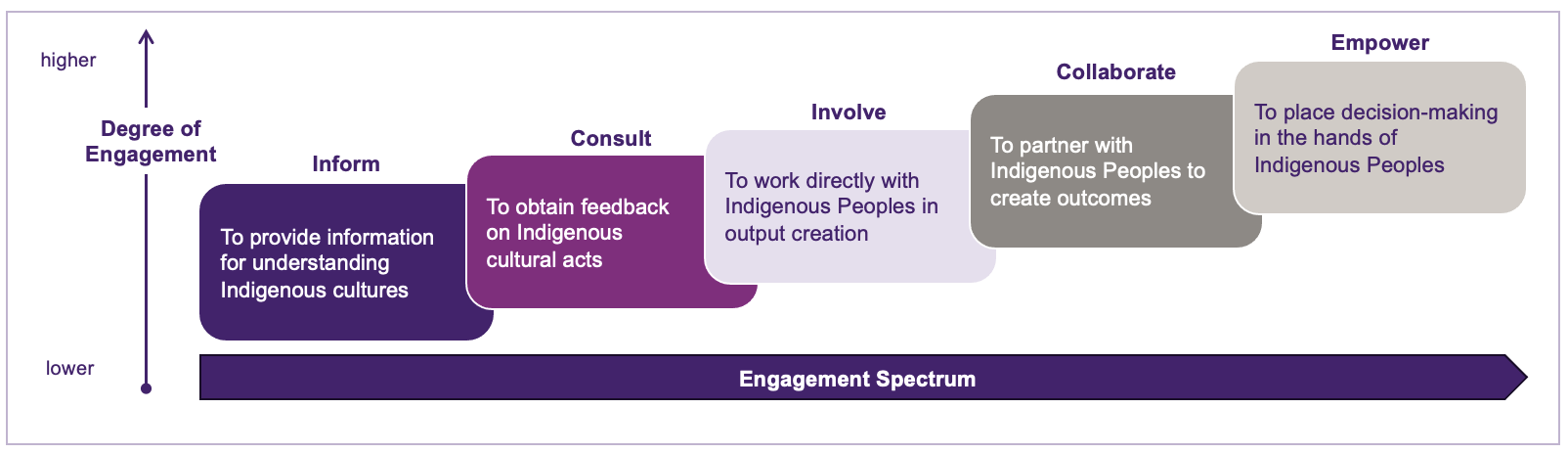

In working to Indigenise our course work, the authors drew on two models for guidance, the first being the engagement spectrum model by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). Figure 1 illustrates the model, which identifies five levels across an engagement spectrum for working with Indigenous peoples and their knowledge systems. The model is based on the public participation spectrum of the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) (Institute of Public Participation, 2018). We found this model very useful as it highlights five types or steps of engagement – Inform, Consult, Involve, Collaborate and Empower – offering various opportunities for sense-making to foster understanding and advance Indigenous peoples’ interests. This approach allows a respectful consideration of the practice of embedding culture into teaching from a theoretical perspective (Ernst et al., 2016).

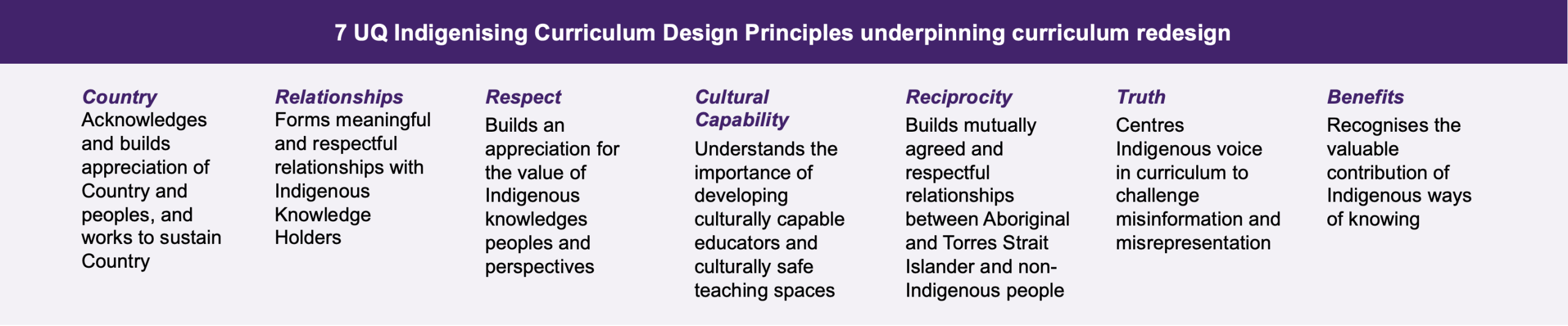

Second, we draw on the Indigenising Curriculum Design Principles (Figure 2) developed by Professor Tracey Bunda and the UQ Indigenising Curriculum Working Party (Bunda, 2022). While this model describes seven principles to be embedded for Indigenising curriculum across a program, one teaching offering (that is, an individual subject/course) is unlikely to include all seven design principles. Within the model, foundational sources of Indigenous knowledge are clarified (e.g., Country) and expectations for UQ’s Indigenous teaching and learning are specified. For example, Indigenising curriculum is done in partnership with Indigenous knowledge holders (e.g., the design principle of Relationships). The model’s purpose, therefore, is to support educators in identifying, designing and developing appropriate Indigenous content for diverse curricula and student cohorts. It seeks to build capacity for all UQ educators to establish successful relationships with Indigenous people.

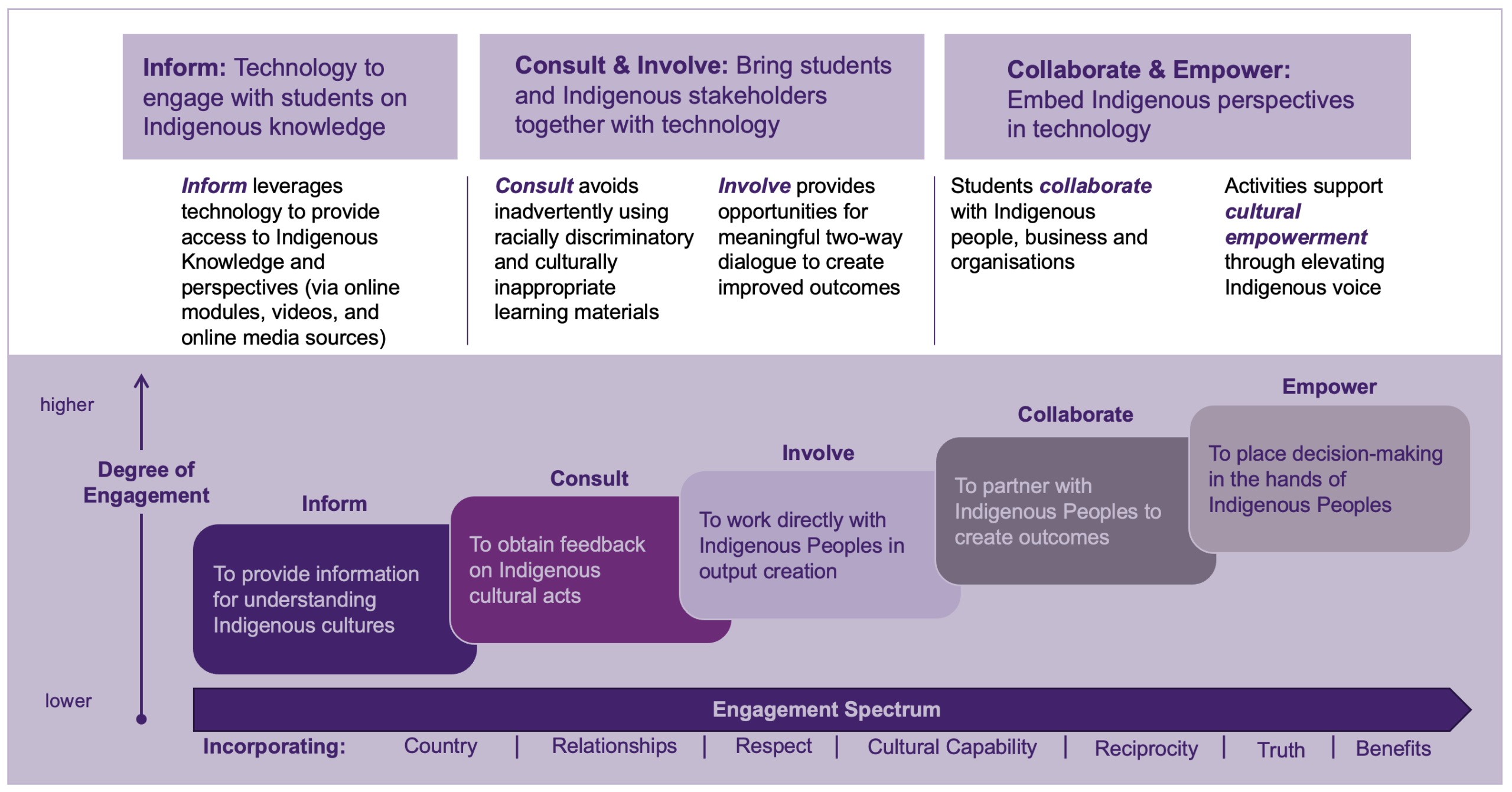

For Indigenous teaching and learning in the UQ Business School, we aligned the two models by integrating Bunda’s (2022) design principles with the five degrees of engagement spectrum (Figure 3). At each stage of the engagement spectrum, we considered the design principles to ensure that the Indigenising work we do in the School aligns with the overarching UQ Indigenising curriculum strategy. By aligning the two models, we do not privilege one knowledge group over another. Importantly, our integrative model is not linear, and not all engagement types need to be applied. Rather, choices need to be made regarding the best approach to ensure meaningful engagement, depending on the number of people involved and the intensity of the engagement required.

Description of UQ Business School pathway for Indigenising curriculum

Overview of courses and design principles

This chapter presents the eight courses (four IS and four management-focused courses, drawn from undergraduate, postgraduate, executive education, student outreach and MBA programs) that serve as data for the reflection on Indigenising curriculum with technology in the UQ Business School. Table 1 provides an overview of the data. The corresponding text presents each course and details the connection to the seven Indigenising Curriculum Design Principles.

The contributing authors include Indigenous and non-Indigenous University staff, that is, teachers, course coordinators and learning designers. Each contributor provided individual reflections on the process of Indigenising their curriculum and the extent to which technology was used. In collating the individual accounts, we sought answers to two key questions: (1) How was each course curriculum Indigenised, and (2) How was technology used in course Indigenisation? These answers are summarised in Table 1, and explained in more detail following that, with each course highlighting which design principle/s underpinned its Indigenisation.

Table 1. Overview of the Indigenising Curriculum Design Principles embedded in eight individual courses

| Course (case) details | Design principles | Indigenising activities | Digital technology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.

IS Analysis & Design ≈211 Master of Business postgraduate students (IS) |

Respect

Relationships Reciprocity |

Indigenous business functioned as client

Materials on culturally infused analysis and design activities |

Development of a low-code application (app)

Agile practices with Indigenous stakeholders: requirements elicitation, acceptance testing, Interface design with cultural symbols |

| 2.

IT for Business Value ≈40 MBA postgraduate students (Management/IS) |

Respect

Benefits |

Case studies with Indigenous context

Student yarning circles Simulations of Indigenous peoples’ contexts and needs |

Web-based resources provided via specially curated repositories

Browser-based simulation creating an interactive experience of IT investment decision-making |

| 3.

Re-imagining Healthcare ≈14 Graduate Certificate in Clinical Informatics and Digital Health students (IS) |

Respect

Benefits |

Culturally safe practices

Digital health strategies for Indigenous communities Data use, ethics and sovereignty |

Online learning modules including more than 20 filmed interviews

Zoom/Teams to share Indigenous content and present to Indigenous stakeholders Online access to journal articles |

| 4.

Introduction to IS ≈40 high school students 14–17 years old (student outreach program – focus on IS – 2 courses) |

Benefits

Country |

Exploration of the ways in which IS and other technology can support issues (i.e., caring for Country) that matter to Indigenous students | PowerPoint presentations and videos of Indigenous knowledges and practices

Development of a web-based simulation dashboard |

| 5.

Managing Organisational Behaviour ≈197 Master of Business postgraduate students (Management/ HR) |

Respect

Benefits |

Indigenous culture and governance

Indigenous leadership Cultural awareness |

Online learning modules embedded into course delivery (including video, podcasts, interactive elements and media)

Online access to journals |

| 6.

Leading People & Teams ≈40 MBA students/ postgraduate students (Leadership/ Management) |

Respect

Benefits |

Indigenous leadership models

Indigenous culture and governance Storytelling: history embedded in Indigenous ways of knowing and doing |

Filming student yarning circles

Video interviews and Indigenous storytelling via Learning Management System (LMS) Online access to journal articles |

| 7.

Leading & Managing People ≈192 Bachelor of Business Management undergraduate students (Leadership/ Management) |

Respect

Benefits |

Indigenous leadership

Indigenous culture and governance Storytelling: history embedded in Indigenous ways of knowing and doing |

Online learning modules embedded in course delivery (including video interviews, news articles, podcasts, media and interactive elements)

Online access to journal articles |

| 8.

Learning the Practice of Leadership ≈18 executives (industry and government) (Leadership – 2 courses) |

Respect | Indigenous cultural awareness technology-aided search for information in both the digital realm (online) and physical realm (geolocation of sites) | Web map software and search tools (Google, Google Maps and Wikipedia)

Mobile phones for verbal communication, tracking time and digital photography Group messaging apps (e.g., WhatsApp) |

Course 1. Information System Analysis and Design: Respect, Relationships, Reciprocity

This postgraduate-level course focused on the design principles of Respect, Relationships and Reciprocity. In this course, students collaborated with Indigenous people to develop a software application (app). Throughout the semester, students collected the requirements and then implemented them using a low-code platform.

In doing so, respect is demonstrated, as Indigenous knowledges and perspectives are integral to the appropriate design and functionality of the app designed by the students. Meaningful relationships were developed with local Indigenous businesses that interacted with students throughout the course and who, in turn, received in-kind remuneration in the form of a functional app for their business purposes. This demonstrated reciprocity in the teaching and learning space, as students and teaching staff engaged in partnerships with local Indigenous businesses that were mutually beneficial.

Course 2. Information Technology for Business Value: Respect, Benefits

This postgraduate-level course forms part of the UQ Business School MBA coursework offerings, providing students with the leadership skills needed in a sustainable digital enterprise. The Indigenisation of this course curriculum incorporated the design principles of Respect and Benefits. In doing so, respect and appreciation of Indigenous knowledges and perspectives were incorporated into the teaching ethos, with students gaining an overall benefit through an enhanced understanding and appreciation of diverse Indigenous contexts, along with how technology can aid in tailoring informed context-specific solutions. Specifically, the redesign included a module on Indigenous communication techniques and leadership styles, a case study on the innovative Cherbourg Service Centre (the first call centre in a First Nations community in Australia), and a guest speaker addressing Indigenous leadership and communication aspects arising from this case. The overall aim of the design change was to increase student awareness of Indigenous concerns and communication techniques, as opposed to the take-up of technology, and to focus on the University’s graduate attributes of developing students as courageous thinkers and respectful leaders.

Course 3. Re-imagining Healthcare: Respect, Benefits

This online course is offered as part of the Graduate Certificate in Clinical Informatics and Digital Health, developed in partnership with Queensland Health and the Digital Health Cooperative Research Centre. The learning places a heightened importance on collaboration and leadership in multidisciplinary, multi-organisational environments. It seeks to empower students to positively change society by applying technology in complex healthcare systems. In doing so, this course focuses on the design principle of Respect through enriching students’ respectful awareness and understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives and needs in relation to the delivery of healthcare, through the incorporation of Indigenous content and with Indigenous organisations. This is achieved through the inclusion of more than 20 filmed interviews with Indigenous stakeholders and carefully curated online articles drawing students’ awareness to sensitive issues related to Indigenous healthcare and misinformation. The design principle of Benefits is realised by students benefiting through being challenged to shift their perspectives and adopt culturally sensitive and appropriate practices to explore issues and solve problems.

Course 4. Introduction to Information Systems: Benefits, Country

This short course is part of a student outreach program designed to engage and inspire Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander high school students to further their studies at university and broaden their career possibilities. In this introductory course, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students explored the role of emerging technologies in supporting issues that matter to Indigenous communities, such as caring for Country. The Indigenisation of this program’s session focused predominantly on the design principle of Benefits. Students participated in a hands-on simulation activity chosen because it embeds important and relevant aspects of topics like caring for Country, collaboration and storytelling. The activity focused on harvesting fish from the sea, but incorporated an inherent challenge in that the sea can be depleted very quickly if overfished. The simulation reveals dynamics that take years to unfold in the real world. Students were empowered through exposure to new learning pathways and technology. In doing so, students gained an understanding and appreciation that information systems are not just about technology, but about solving problems and addressing important social issues, and that information systems can be harnessed and shaped to be used (or not) in different ways.

Course 5. Managing Organisational Behaviour: Respect, Benefits

This postgraduate-level course aims to provide students with the skills and confidence to understand diverse human behaviour in workplace settings. Through the course, students become more self-aware of their own behaviours and biases to become better able to manage themselves and others. The design principles of Respect and Benefits are at the core of the Indigenisation of this course curriculum, where respect of others helps to develop students’ awareness of alternative people-management practices and appreciation of diversity of cultures and perspectives, including those of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, in workplaces. Online repositories provide students with access to carefully curated journal articles, readings, interviews and media clips to help expand their worldview. As such, benefits are gained as students are encouraged to take a strengths-based approach to Indigenous people’s engagement strategies, such as relationality and deep listening.

Course 6. Leading People and Teams: Respect, Benefits

Forming part of the UQ Business School MBA coursework offerings, this postgraduate-level course aims to develop those currently in leadership and management roles to actively reflect on and improve current leadership practice needed in contemporary times. The course focuses on the design principle of Respect by providing opportunities for students to develop their awareness and understanding of relationality, storytelling and deep listening as effective people-management practices. The design principle of Benefits is enhanced through challenging students to apply learnings in their current work practices. This learning predominantly takes place in two key modules in the course (one focused on interpersonal and intergroup communication, and the other on change management and communication), augmented by recorded interviews with Indigenous knowledge holders and access to online articles by Indigenous authors.

Course 7. Leading and Managing People: Respect, Benefits

This second-year undergraduate course aims to prepare future leaders with the skills, confidence and capability to effectively lead and manage people. With “people” at the centre of this course, the focus is on the Respect and Benefits design principles, with the intention that students gain an understanding and respectful appreciation of the value of Indigenous models of leadership and relationality in effective people-management practices. is achieved through storytelling both in class and via recorded interviews in online coursework materials. Carefully curated articles and links to online content are also provided to ensure students gain a balanced perspective of leadership and ways of leading, as well as appreciate the value of diversity. Benefits are achieved through adopting a strengths-based perspective of leadership and management practices to explore Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing. As such, this course aims to broaden students’ appreciation of alternative practices that have stood the test of time.

Course 8. Learning the Practice of Leadership: Respect

This UQ executive education course provides those aspiring to leadership positions with a series of practical leadership learning challenges to help develop the self-awareness, skills and confidence to motivate others. Respect is the key design principle embedded in this course. One activity in particular, The Hunt, aims to simultaneously provide a platform for learning to lead while raising students’ awareness of the negative effect of colonisation in the heart of the Brisbane CBD. Students are encouraged to use all forms of technology at their disposal to complete the activity in the nominated timeframe. Rather than explicitly being told the key learnings, students instead piece together an overall impression through discovering clues and having collaborative discussions on how these fit together. Consequently, this experiential learning activity provides students with a rich “ah-ha moment” that they report has a lasting impact.

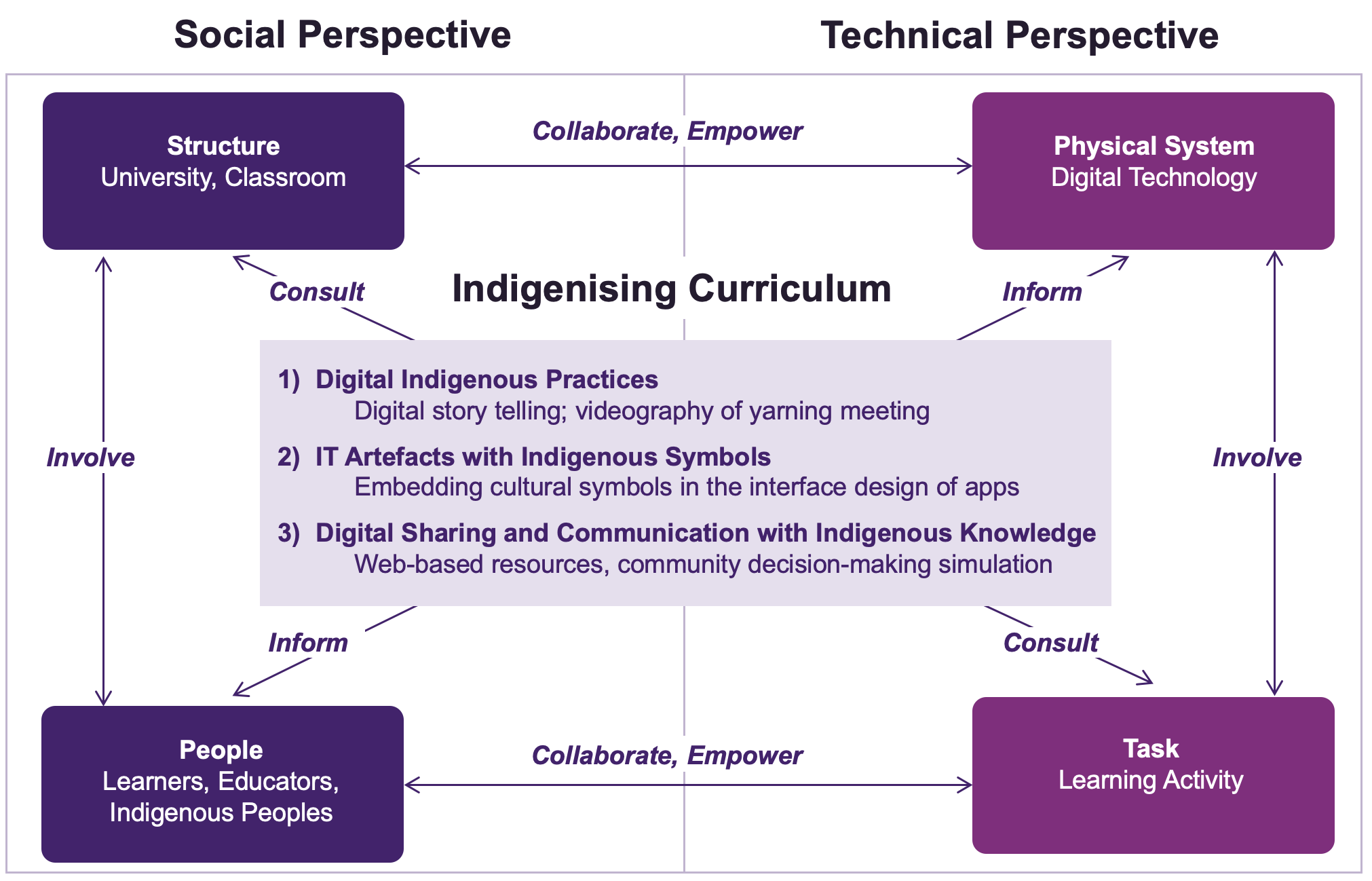

Theoretical lens for integrating Indigenous knowledges, cultures and perspectives with technology

When the authors looked to Indigenise the curriculum in their courses, they wanted to do so in a research-informed way; however, it was unclear what framework to use. After much reflection, the team deemed a socio-technical framework as helpful because socio-technical system theory (Table 2) emphasises the simple but important idea that, when you create, use or adapt technology in real-world settings, you must consider both social issues (e.g., human knowledge, ability and skill) and technical issues (e.g., tools, mechanisms and techniques), and their interrelationships. By emphasising both sides of the coin, the theory also suggests that we should consider both humanistic outcomes (such as enjoyment and meaning) and instrumental outcomes (such as improved knowledge of a task) (Cecez-Kecmanovic et al., 2014; Ryan et al., 2002; Sarker et al., 2019).

Table 2. Socio-technical system components (adapted from Ciriello et al., 2024, p. 3)

| Component | Definition |

|---|---|

| People | “The people component represents the key human actors and their associated stakeholders involved in a socio-technical system.” |

| Structure | “The structure component … encapsulates the overall cultural, institutional and behavioural principles.” |

| Task | “The task component … involves the main sequence of practices to achieve an overarching goal.” |

| Technology | “The technology component … refers to the problem-solving tools used to accomplish a task.” |

Over time, the study of socio-technical systems has shifted from focusing on the interactions between social (human aspects) and technical (technological systems) components to a more integrated perspective that views these elements as part of a unified system (Molleman & Broekhuis, 2001). Indeed, empirical research has consistently shown that, while technology generally performs reliably, the outcomes from its implementation and use are significantly influenced by the dynamics within the socio-technical system itself (Baskerville & Pries‐Heje, 2001; Bostrom et al., 2009; Clegg, 2000; Matook & Brown, 2017). This important focus stems from factors such as the interpretation of technology and its suitability for specific tasks and settings. Guided by this theoretical framework and the expertise of information systems scholars in our team, we adopted a similar approach in our initiative to Indigenise the curriculum through technology, as outlined in the next section.

Approaches for Indigenising curriculum with technology

In reflecting on our Indigenising curriculum efforts, we identified three main approaches that have framed our work and the role of technology as an enabler (Figure 4): Digital Indigenous Practices, IT Artefacts with Indigenous Symbols, and Digital Sharing and Communication with Indigenous Knowledge.

Inform: Technology to engage with students on Indigenous knowledges

We sought to support the Inform step of the engagement spectrum by integrating the social subsystems of structure and people (Figure 4) tightly with the technical subsystems (various technology components). Different learning applications facilitated learning activities that provided information regarding Indigenous knowledges and perspectives via online learning modules, video interviews and online media sources. Here, technology provides students with access to knowledge that they would not easily have otherwise. For example, course 3 (Table 1) learnings incorporated over 20 video interviews with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander healthcare professionals and industry experts, providing students with an in-depth understanding of the concerns, needs and strategies trialled without the need to travel to rural and remote locations. For instance, videos on the topic of data sovereignty helped students appreciate the need to empower Indigenous communities to collect, learn from, and protect data about their communities, and students were able to apply their understanding of Indigenous data issues to build strategies for an Indigenous healthcare organisation. Feedback from the organisation was highly positive.

As a further example, courses 2, 3, 5 and 7 (Table 1) utilised online learning platforms and tools that the course coordinators believed to be considerably more engaging than traditional textbooks. The platforms were novel to the students, thus motivating them to engage with the interactive learning materials. In these courses, technology provided students with rich, in-depth learning experiences they would not have otherwise had access to.

These examples demonstrate how appropriately selected technology can effectively enrich students’ learning about Indigenous knowledges and perspectives.

Tips

Tips

- Locating suitable resources and content is the course teacher’s responsibility. However, when aiming to raise students’ awareness and understanding of Indigenous knowledges and perspectives, it is important to ensure that the content is appropriate and reflects a strengths-based approach. In this way, we contribute to shifting the mainstream perception of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

- It is important that unbiased reporting is identified for when you want students to consume news. However, online materials are not always from trusted sources. Such materials may serve as appropriate materials to raise awareness of biased reporting and the reinforcement of stereotypes.

- It is important not to expect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander colleagues to do the work of reviewing your choice of materials. For support, seek out an Indigenising curriculum community of practice (or equivalent) to join (and, if not yet available in your institution, advocate for its establishment).

Consult and Involve: Bring students and Indigenous stakeholders together with technology

The Consult engagement step uses feedback processes for adopting technology-enabled learning materials to address Indigenous cultures. UQ has established structures to support a social system rich in Indigenous knowledges. In UQ Business School, this includes hiring several Aboriginal academics and professional staff, including a dedicated Indigenous learning designer. This enabled educators across all courses (Table 1) to seek feedback on how to incorporate cultural practices, as well as support their teaching with different technologies. In course 2, for example, while a diverse range of online materials (videos, podcasts, articles) was provided for students, this selection was a carefully curated collection of materials selected by the Indigenous learning designer and recommended by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander academic staff from within the School and in relevant Faculties across the University. We found that seeking consultation and feedback on resources to use is important because the technical subsystem (that is, the Internet) can provide access to all kinds of Indigenous resources, including those that are racially discriminatory, misappropriated, and culturally inappropriate, such as meaningless pictures in advertisements.

The Involve engagement step provides opportunities for meaningful two-way dialogue to create improved outcomes. We learned from the data that dialogue can discourage certain interactions with the technical subsystem while proposing culturally appropriate alternatives. For example, courses 4, 6 and 8 (Table 1) offered learnings from the practice of traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander meetings, such as yarning circles, to enhance the way in which students conduct meetings. These learnings included making space for relationship-building, checking in with each member to get a sense of how they are feeling, being respectful and making time for all participants share their views, and recognising there is no single leader; rather, it is a collaborative process for addressing issues, solving problems, and making decisions in a caring and constructive way. By taking time to connect at the human level, students recognised that the quality of their dialogue was more meaningful, and they were able to truly hear and learn from other people’s perspectives. Feedback indicated it was better not to use Zoom technology for these more relationally focused meetings in order to preserve the human interaction important to this practice. Instead, these meetings were enriched with an online repository of Indigenous stories accessible for all students before and after the in-person activity. A different direction was taken in course 3 (Table 1), whereby a yarning circle conducted with the students was filmed and the video was made available online (through the e-learning platform) for future courses to use as a resource.

Tips

Tips

- To provide a more in-depth and rich learning experiences for students, your university’s central learning design team (or equivalent) can provide support on how to restructure your course, as well as recommend the most appropriate people to connect with for additional advice. Allow sufficient lead time and be prepared to do the required work following their advice.

- Any filming required will need additional permissions, lead time and potential payment.

- Recognition must be given to Elders and other cultural knowledge holders for their time and expertise. This may take the form of financial or in-kind compensation, which is to be agreed upon prior to their involvement. Overall, be mindful of not overburdening Indigenous people (including your Indigenous colleagues).

Collaborate and Empower: Embed Indigenous perspectives in technology

The development of a new information system allowed students to implement the Collaborate step with Indigenous businesses, while the Empower step was experienced by handing over decision-making power in the app development process to Indigenous people. In course 1 (Table 1), for example, the learning task was the design and development of a low-code registration app for a sports provider of netball programs. The Indigenous people involved in the course served as the client. During requirements elicitation, as part of the collaboration process, students learned about racial discrimination against Indigenous netball players from their Indigenous client.

The app development enabled Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander learning, as students embedded cultural symbols into its functional design and layout. For example, the app/company logo is a ball that looks like the sun and symbolises an Aboriginal meeting place by only using the colours associated with the Australian Aboriginal flag (yellow, black, red). Cultural learning also became critical in moments of cultural misappropriation and subsequent reflection when, for example, some students “Google-searched” random Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander images to add to the app, none of which had cultural connections with the client’s Indigenous culture.

The app development task also supported cultural empowerment, as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices were heard in agile instructional design and development practices, particularly in requirements elicitation, acceptance testing and app showcases.

Tips

Tips

- When creating a product or service at the Collaborate and Empower levels, bring Indigenous knowledge holders into the classroom early and often. Without Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices and ideas, teaching and learning experiences lack authenticity.

- When working with Indigenous knowledge holders, value and respect their time through handing over the created product or service, other in-kind remuneration or direct payment.

- To avoid neglecting your core teaching and learning responsibilities, you may need access to additional personnel and resources to manage the close relationships with Indigenous people (for example, learning advisors and work-integrated learning personnel). Identify and discuss resourcing needs early with your program or discipline leader (or equivalent).

Coming-together

This chapter contributes to the IS literature for Indigenising curriculum by bringing to light the role of technology in enhancing the appreciation of Indigenous cultures and knowledges in university classrooms. Specifically, we present initial findings on how Indigenising curriculum and developing students’ cultural capabilities unfold in socio-technical systems.

We drew on data from eight UQ Business School courses that infused the Indigenising of course curricula with technology in different ways. We incorporated the theoretical framework for engagement with elements from socio-technical systems theory, using this lens to elicit technology-rich educational practices. Through the explorative reflections of the involved educators, we developed an integrated framework identifying three Indigenising curriculum approaches: Digital Indigenous Practices, IT Artefacts with Indigenous Symbols, and Digital Sharing and Communication with Indigenous Knowledge (Figure 4). This study is an important outcome, given that the research occurred in an early phase of the University of Queensland establishing Indigenising curriculum as a strategic learning and teaching priority.

As to be expected, the people component in the social subsystem (Figure 4) plays a key role, given that it encompasses both the source and audience of Indigenous learning. Working with Indigenous learning designers and partnering with Indigenous stakeholders was found to be an essential enabler for Indigenous socio-technical interactions, something we are still at an early stage of fully appreciating and addressing, and which we need to explore in more detail in the future.

As technology provides a channel for sharing knowledge with students, the Inform engagement step was achieved via students’ interactions with technology. The interactions between structures and people enabled Involve engagements, as the structures of the social system provide a real-world place for Indigenous knowledges to manifest. Further, the interactions between the social and the technical subsystems – structure, physical system, people and task (Figure 4) – enabled the engagement steps of Collaborate and Empower. The structures emerge during learning, and the learning tasks draw on people to create artefacts. Finally, to ensure that authentic and truthful Indigenous knowledges are shared with students, we suggest that the interactions between structure and task provide an opportunity for feedback, thus enabling Consult as an engagement step.

Once the writing of this chapter was completed, we reflected on where the future may lie for Indigenising curriculum with technology, and the implications in how it is used. Technology has advanced with generative AI to the extent that multimodal social robots already support learners and educators in multiple ways (Elkins et al., 2024). When robots can now understand and respond to speech, visual cues and nonverbal signals from learners, they could also be programmed to provide extensive learning for Indigenising activities. Building on this, we reflected on the need to critically examine the ethical implications of using AI in educational settings, particularly regarding its potential to generate biased or harmful content and to perpetuate cultural misrepresentation. To mitigate these risks and prevent further widening of the cultural gap, it is essential to establish comprehensive frameworks that promote ethical use of AI while ensuring that genuine and authentic Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices are not only included, but celebrated and respected.

Reflection questions

- How can we ensure that any forms of technology we use to support and enrich our teaching contribute to cultural enhancements and a better appreciation of Indigenous knowledges and perspectives?

- How can artificial intelligence (AI) robots support the teaching and learning of Indigenous cultures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples regarding the Indigenising Curriculum Design Principles of Respect, Relationships, Country, Truth, Cultural Capability, Benefits and Reciprocity?

- How can we ensure that any use of AI in our educational settings not only addresses the ethical implications of bias and cultural misrepresentation/misappropriation, but also actively incorporates, honours and values Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges and perspectives in our teaching practices?

References

Baskerville, R., & Pries‐Heje, J. (2001). A multiple‐theory analysis of a diffusion of information technology case. Information Systems Journal, 11(3), 181–212.

Bostrom, R. P., Gupta, S., & Thomas, D. (2009). A meta-theory for understanding information systems within socio-technical systems. Journal of Management Information Systems, 26(1), 17–48.

Bostrom, R. P., & Heinen, J. S. (1977). MIS problems and failures: A socio-technical perspective. Part I: The causes. MIS Quarterly, 1(3), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/248710

Bunda, T. (2022). Indigenising curriculum: Consultation green paper. Office of the Pro Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement) and Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation, The University of Queensland.

Cecez-Kecmanovic, D., Galliers, R. D., Henfridsson, O., Newell, S., & Vidgen, R. (2014). The sociomateriality of information systems. MIS Quarterly, 38(3), 809–830.

Ciriello, R. F., Richter, A., & Mathiassen, L. (2024). Emergence of creativity in IS development teams: A socio-technical systems perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 74, Article 102698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102698

Clegg, C. W. (2000). Socio-technical principles for system design. Applied Ergonomics, 31(5), 463–477.

Elkins, A., Amadasun, U. P., & Matook, S. (2024, September 16–20). Personalized learning artificial intelligence: Exploring multimodal social robotics in the classroom [Conference presentation]. European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning, The 2nd International Workshop of the EATEL SIG EduRobotX, Krems, Austria.

Ernst, S. J., Janson, A., Söllner, M., & Leimeister, J. M. (2016, December 11). It’s about understanding each other’s culture – Improving the outcomes of mobile learning by avoiding culture conflicts [Conference paper]. International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), Dublin, Ireland.

Gainsford, A., & Evans, M. (2017). Indigenising curriculum in business education. Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues, 20(1), 57–70.

Institute of Public Participation. (2018). IAP2 spectrum of public participation. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/Spectrum_8.5x11_Print.pdf

Matook, S., & Brown, S. A. (2017). Characteristics of IT artifacts: A systems thinking‐based framework for delineating and theorizing IT artifacts. Information Systems Journal, 27(3), 309–346.

Molleman, E., & Broekhuis, M. (2001). Socio-technical systems: Towards an organizational learning approach. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 18(3), 271–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0923-4748(01)00038-8

Ryan, S. D., Harrison, D. A., & Schkade, L. L. (2002). Information-technology investment decisions: When do costs and benefits in the social subsystem matter? Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(2), 85–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2002.11045725

Sarker, S., Chatterjee, S., Xiao, X., & Elbanna, A. (2019). The socio-technical axis of cohesion for the IS discipline: Its historical legacy and its continued relevance. MIS Quarterly, 43(3), 695–720.

Universities Australia. (2022). Indigenous strategy 2022–25. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/10783915/universities-australia-indigenous-strategy-2022-25/

Weiss, K., Hamann, M., & Marsh, H. (2013). Bridging knowledges: Understanding and applying Indigenous and Western scientific knowledge for marine wildlife management. Society & Natural Resources, 26(3), 285–302.

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing.