3 Walking together

Culturally responsive ways of working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities

Kate Thompson and Karina Maxwell

School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work

Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians, the Turrbal and Yuggera peoples, of the lands on which we live, work and study. We endeavour to respect and take care of Country like our Ancestors have for thousands of years before us. We would like to pay our respects to Elders past, present and future and any Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reading this chapter, recognising that this land now known as Australia was never ceded. Always was, and always will be Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander lands.

A note on terminology

Throughout this chapter, we use the terms “Aboriginal peoples” and “Torres Strait Islander peoples” to respectfully refer to the Traditional Custodians of this country now known as Australia. When discussing Indigenous peoples globally, we use the term “Indigenous peoples”. While there may be overlaps and nuances in terminology, our goal is to use the most appropriate term in each context, ensuring culturally safe and respectful communication.

Introduction

This chapter illuminates how we are Indigenising the curriculum in the School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work at The University of Queensland (UQ). We will draw on our experiences of coordinating and teaching in the course Working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Families and Communities for nursing, midwifery and social work undergraduate students, and nursing and social work postgraduate students. This course aims to transform knowledge and practice skills through critical reflection to work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities in a culturally safe and responsive way.

The purpose of this chapter is to outline a practical pedagogical process that can guide students’ journeys towards culturally safe and responsive practices. Throughout the chapter, we demonstrate how our pedagogy aligns with many of the Indigenising Curriculum Design Principles, including Country, Relationships, Respect, Reciprocity and Truth (Bunda, 2022). This chapter will (1) introduce the authors, cultural safety framework and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being and doing (2) introduce the concept and model of Reflect. Unlearn. (Re)Learn. Plan. (3) explore the necessity of understanding cultural protocols and (4) examine the role of discourse in shaping practice and its implications. This chapter provides practical pedagogical tools that can be transferable to different learning domains and disciplines.

About the authors

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander protocols are relational, highlighting the importance of connectivity and recognising that relationships are central to social, cultural, and spiritual life (Martin / Mirraboopa, 2003; Tripcony, 2006). In line with cultural protocols, we will firstly share our positionality.

Karina Maxwell: I am a proud Ngugi woman from the Quandamooka Nation, born and raised in Naarm (Melbourne) before moving to Meanjin (Brisbane) in 2001 and studying a Bachelor of Social Work at UQ. Most of my career has been working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families in intensive family support, in both mainstream organisations and an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community-Controlled organisation (ATSICCO). Other areas of work include mental health, crisis accommodation and child protection.

Kate Thompson: I am a proud Gooreng Gooreng and Yuggera woman. My connections to Gooreng Gooreng peoples and Country are through my paternal grandmother, and my connections to Yuggera peoples and Country are through my paternal grandfather. I was born and raised in Bundaberg, Queensland, and later moved to Meanjin (Brisbane)to study a Bachelor of Social Work (Honours) at UQ. I have experience working in an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Organisation (ATSICCO) with non-Indigenous and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander foster and kinship carers, who were caring for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the out-of-home care system.

Walking together

We have worked together on numerous occasions beginning with a shared space in the same ATSICCO. We were both approached to work into the course Working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Families and Communities in its inaugural year, 2018. We have worked into this course consistently since its inception by tutoring, marking and lecturing before commencing in 2023 as course co- coordinators.

As PhD students, we’ve shared the journey of exploring the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families within the child protection system. This shared experience has deepened our common vision, passion and commitment to improving outcomes for our people. Throughout this chapter, when discussing the work undertaken together, Karina and Kate will be referred to as “we” or “our”. That is not the “royal we” that a monarch or someone in high office refers to themselves as, but is in line with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural concepts of collectiveness.

Below, we explore the principles that inform and shape our pedagogical approach in teaching.

Defining cultural safety

The concept of cultural safety was developed by Dr Irihapeti Ramsden and colleagues in Aotearoa (New Zealand), arising from the colonial context of the health care system (Papps & Ramsden, 1996). The concept of cultural safety, initially conceived within the nursing and midwifery professions, has subsequently been adapted and implemented across various health and human services disciplines, particularly in the context of Indigenous cultures. Cultural safety is defined by Ramsden (2002) as “an outcome of nursing and midwifery education that enables safe service to be defined by those that receive the service” (p. 117). As educators, we often hear students and health care and human service practitioners state that they provide care to patients regardless of cultural identity. However, the concept of cultural safety emphasises the obligation of practitioners to provide care that is respectful toward, and inclusive of, people’s cultures, values and beliefs (Papps & Ramsden, 1996; Ramsden, 2002).

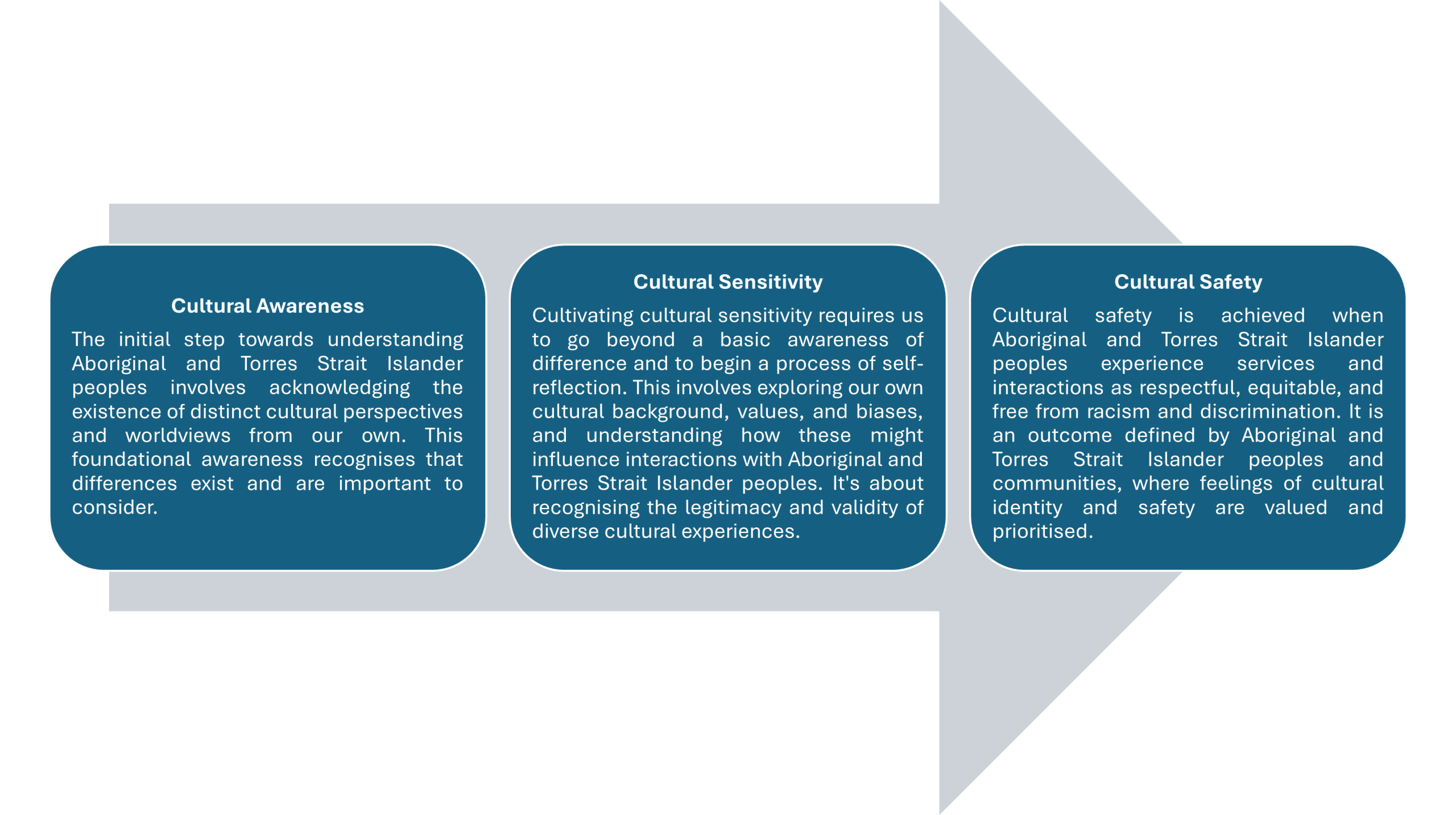

Importantly, the concept of cultural safety shifts the practitioner focus from a need to understand or be competent in another person’s culture, to instead focus on the culture/s of the practitioner and how these cultures, values and beliefs may impact and influence their work (Papps & Ramsden, 1996; Ramsden, 2002). Culturally unsafe practice is therefore defined as any omission or action that disempowers, demeans or diminishes the cultural identity and wellbeing of a person (Papps & Ramsden, 1996, p. 493). Ramsden articulates a process toward achieving cultural safety for nursing practitioners, as demonstrated in Figure 1 (2002, p. 117), which serves as a valuable, adaptable model for implementation in any domain or discipline.

As demonstrated above, cultural awareness requires practitioners to begin to critically reflect and identify their own cultures, values and beliefs. Cultural sensitivity is about practitioners becoming aware of how their cultures, values and beliefs may impact and influence practice and recognise that our cultures, values and beliefs differ to those we are working with. Finally, cultural safety occurs when we are conscious of our individual cultures, values and beliefs; are able to consider the cultures, values and beliefs of those we work with; and adapt our practices to be inclusive of these differences, accommodating the needs of those we are working with (Papps & Ramsden, 1996; Ramsden, 2002). Throughout this chapter we will refer to this core concept.

Tip

Tip

To engage students with Ramsden’s journey, we prompt students to critically reflect on their current position and to provide a justification. We repeat this activity at the end of the semester. This encourages students to recognise their growth and identify areas for further development. For example, Karina, a Ngugi woman, often positions herself between cultural sensitivity and cultural safety, acknowledging the ongoing learning journey and the need to understand the diversity of cultures.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being and doing

Central to our personal and professional frameworks is the recognition of Aboriginal ways of knowing (epistemology), being (ontology) and doing (axiology) (Martin / Mirraboopa, 2003; Moreton-Robinson, 2013). While the term “Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing” is widely used globally and within Australia, it is important to emphasise that, to model culturally respectful and inclusive practice, the term we use will also encompass Torres Strait Islander peoples. From here on in the term in this chapter will be referring to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being and doing.

Ways of knowing involve collaborative social, political, historical and spatial learning processes. Knowledge is shared across generations by families, Elders and community leaders, with each person holding knowledge linked to their specific role. Learning is ongoing, often unconscious, and occurs at various times and interactions.

Ways of being emphasise that identity is shaped through relationships with others. Learning, living and growing are influenced by these connections. When introducing oneself, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples share their identity, family and roles to build relationships, a practice that non-Indigenous people should also adopt. Relationship-building is rooted in learning, reciprocity and mutual commitment, though it can be complex, involving tension and conflict, it can lead to personal growth through self-reflection.

Ways of doing combine ways of knowing and being to guide individual and community conduct. These practices are essential for effective cross-cultural collaboration, with sharing power being a key element. We emphasise the importance of a mutual learning process, where the teaching team and students are both knowledge holders and learners. This requires humility and a willingness to continuously learn from others, especially those with lived experiences. Relationship-building, as emphasised in ways of being, is crucial for fostering trust and meaningful connections with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities. It should not be dismissed as a time-wasting activity.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being and doing enhance the richness and depth of the pedagogical framework that shapes this course and allows the teaching team to navigate beyond mainstream paradigms (Martin / Mirraboopa, 2003; Moreton-Robinson, 2013). This approach respects oral traditions, storytelling and community engagement, recognising the interconnectedness of knowledge and lived experiences (Moreton-Robinson, 2013; Rigney, 1999; Smith, 2021). By adopting a holistic lens, we model a teaching style that is a collaborative process, while also acknowledging relationality and context. This ensures the validity of education and contributes to a culturally safe, equitable and respectful learning environment, aligning with the values of reciprocity and mutual benefit for students and staff.

Reflect. Unlearn. (Re)Learn. Plan.

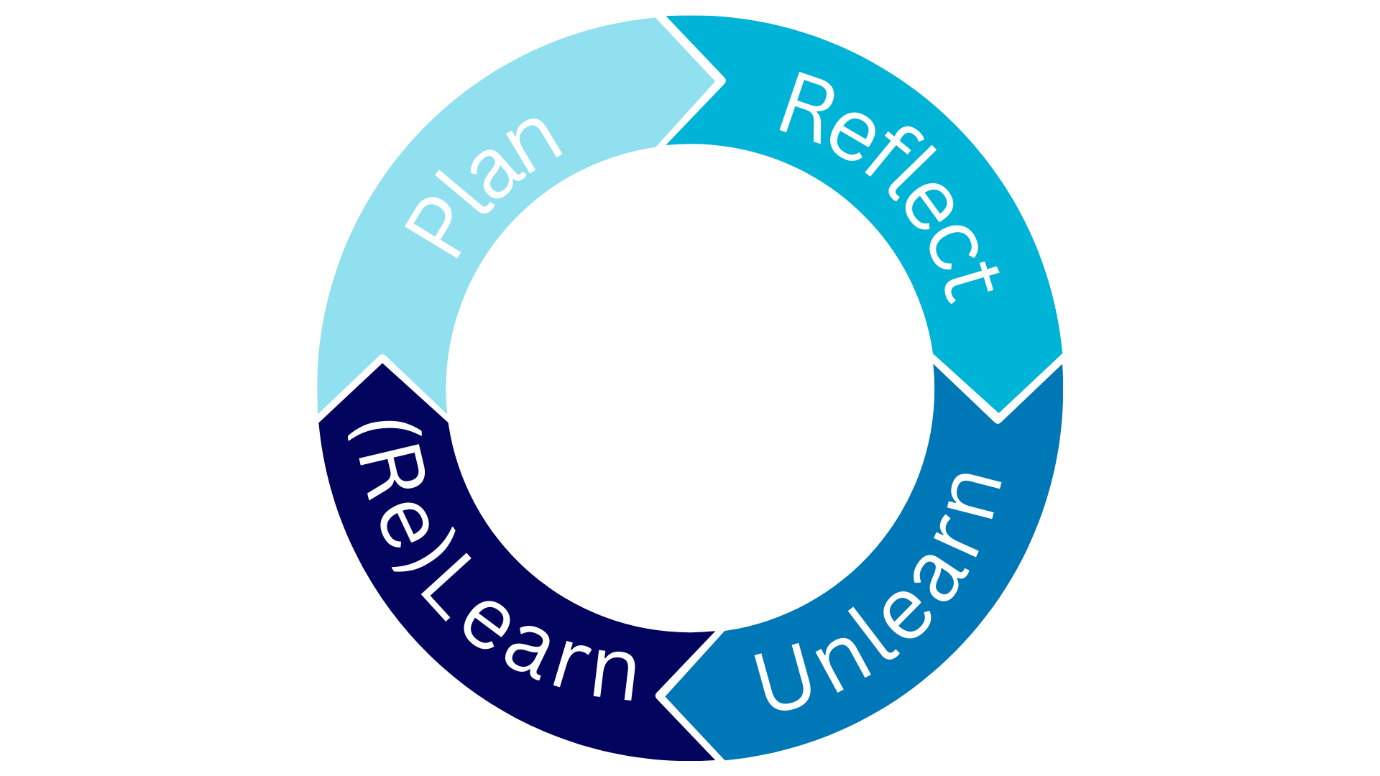

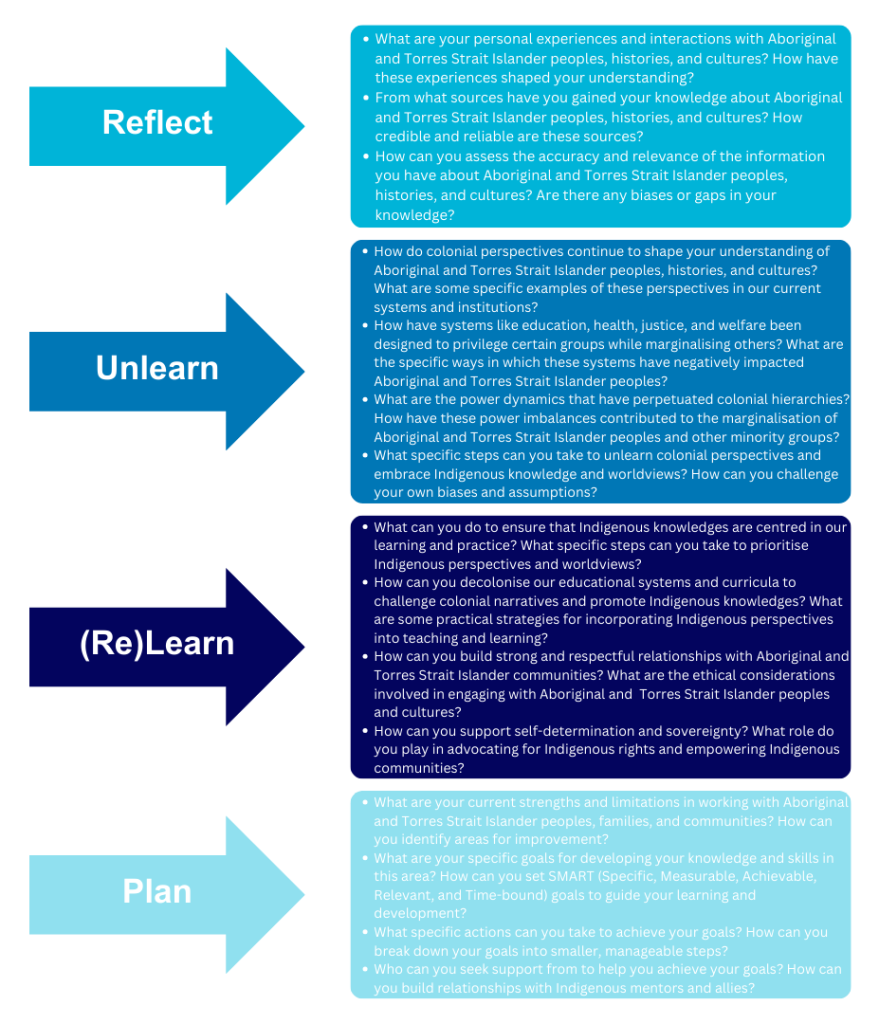

To embark on a journey towards culturally safe and responsive practices, we introduce the cyclical concept of Reflect. Unlearn. (Re)Learn. Plan. (see Figure 2 below). This practical framework guides people and organisations through a process of critical reflection, supporting us to challenge biases and develop culturally safe and responsive practices. This cyclical approach to knowledge acquisition and personal growth empowers us to challenge existing assumptions, embrace new perspectives, and develop a more nuanced understanding of Indigenous histories and cultures.

It is imperative to critically reflect upon our existing knowledge and understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, histories and cultures. This involves identifying and analysing the dominant perspectives and potential biases present within this knowledge. Furthermore, we must assess the relevance, accuracy and reliability of the information, as well as consider the source and perspective from which it has been presented.

To progress, we must unlearn the entrenched colonised perspectives that have been forced upon us. These perspectives are deeply embedded in our systems, which were created primarily for colonisers and often neglect the strengths and needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities, as well as other minority groups. Further, unlearning requires us to acknowledge the biases and limitations of Western education, which often prioritises colonisers’ perspectives and ignores or marginalises Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices, and those of other marginalised peoples. In unlearning, we must critically reflect on the power dynamics that have perpetuated colonial hierarchies.

To progress we must (re)learn from a decolonised perspective. We intentionally use the term “(re)learn” to acknowledge that while some people are relearning, others may be learning for the first time about a specific culture. (Re)learning requires us to centre Indigenous knowledges through recognising the value and validity of Indigenous knowledge systems and how these contribute to understanding the world. After we have critically reflected on the power dynamics that have perpetuated colonial hierarchies, we are then able to work towards developing and delivering services that promote inclusivity and equity.

The next step of the process is to plan. This stage of the process involves a self-assessment of our current knowledge and skills, identifying the strengths and limitations. Based on this assessment, we develop a personalised plan that incorporates achievable action items to support future learning and skill development related to working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities. Figure 3 provides guiding prompts for the Reflect. Unlearn. (Re)Learn. Plan. model.

Our development of this model has enabled us to produce a structured critical reflection approach, as detailed in Figure 3. The questions within this model guide students to critically analyse their internal biases and preconceived ideologies, facilitating (re)learning from a decolonised perspective, and the planning of future learning. This model provides teaching staff with a practical tool to support the Indigenising of the curriculum.

A decolonised pedagogical approach

To support students to adopt the Reflect. Unlearn. (Re)Learn. Plan. model throughout their learning journeys, we conduct structured pedagogical activities to challenge dominant narratives and encourage critical thinking. We must operate by assuming that students have no knowledge of critical reflection, and, therefore, our tutorials introduce students to the concept of critical reflection and various reflective models. This ensures all students have a shared understanding.

After introducing critical reflection, we provide students with activities to practice the skill. For instance, we re-introduce Ramsden’s process toward achieving cultural safety and guide students through self-reflection and peer discussion. See Table 1 for an example of this activity, using an adapted version of Gibb’s reflective cycle (Gibbs, 1988).

Table 1: Example of critical reflection activity

| Question/Prompt | Explanation/Reasoning |

|---|---|

| Define cultural safety | Students are encouraged to define cultural safety, the process to achieving cultural safety (cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity and cultural safety), in addition to culturally unsafe practice. |

| What specific emotions or thoughts arose as you learned about cultural safety in the lecture? | This prompts students to examine their initial reactions to learning cultural safety from an Indigenous perspective. Some students admit to feeling annoyed that they are learning about this concept again, while others share feelings of excitement. Students’ reactions vary significantly, and that’s ok! |

| What specific knowledge or experiences did you have regarding cultural safety or related concepts before starting this course?

How does this prior knowledge compare to what you’ve learned in this course? |

Students are encouraged to further examine their understanding of cultural safety, and to reflect on previous encounters with the concept, the specific information learned and how their perspectives may have evolved. This prompts students to evaluate and analyse their knowledge, as demonstrated by the following example reflection:

“In a previous course as part of my nursing degree, I was introduced to the concept of cultural competence. In my learnings I was told that cultural competence is far more important than cultural safety, as we should always be aiming for competence. However, after participating in lecture 1, I have come to realise that cultural competence may not be the most appropriate thing for my practice. I appreciate Ramsden’s process toward achieving cultural safety, as this process recognises that we don’t have to be competent in learning another person’s culture.” |

| What was a major learning/key takeaway message about this concept? | By reflecting on their key takeaways, students can gain a clearer understanding of the concept, apply it to their own experiences and continue to grow as learners. |

| Reflecting on your learning journey so far, what knowledge gaps have emerged?

What resources or strategies could help you deepen your understanding of these areas? |

Students are guided to develop actionable and achievable plans, rather than broad intentions. Below is an example of a well-structured response:

“After participating in the lecture and tutorial, I realise I don’t understand the nuances of Ramsden’s process toward achieving culturally safe practice. I am particularly confused about the differences between cultural sensitivity and safety. To address this knowledge gap, I will revise the Week 1 lecture content prior to the next tutorial; seek additional learning resources via the Blackboard Learning site and the library reading list; write some questions down to ask my tutor in our next tutorial; participate in the upcoming group discussion to further explore these concepts with my peers; and reflect on my progress in addressing these knowledge gaps in Week 4, adjusting my learning strategies as needed.” |

Further to the examples outlined in Table 1, we incorporate emotional and experiential learning activities into our pedagogy. For instance, in tutorials we listen to Brigg’s song “The Children Came Back” (YouTube, 3m 50s) featuring Gurrumul and Dewayne Everettsmith, building on lecture content around the Stolen Generations. Students are prompted to reflect on the lyrics, visuals and the emotions evoked by the music. Further examples of critical reflection activities are provided in the next section. Through the power of music and visual storytelling, we invite students to reflect on the past, unlearn harmful narratives, (re)learn Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, and plan for a future that honours Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty and cultural integrity.

Our reflections

Our model and conceptual framework Reflect. Unlearn. (Re)Learn. Plan. aligns with the Indigenising Curriculum Design Principles. By encouraging critical reflection, challenging existing knowledge and fostering new understandings, this model embodies the design principles of Country, Relationships, Respect, Reciprocity and Truth. Through this process, students and educators develop an appreciation for the diversity of Country and its peoples, building meaningful relationships with Indigenous knowledge holders based on mutual care and shared practice. By challenging misinformation and centring the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, we aim to cultivate respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and rights. The model fosters reciprocal learning experiences, empowering students and educators to become both learners and teachers. To create space for truth-telling and the unlearning of harmful stereotypes, we must embrace discomfort and challenge existing knowledges we hold.

Tip

Tip

Some students shut down when faced with discomfort, leading them to disengage from the learning/course. Be mindful of students’ emotions and provide support to foster a safe and inclusive learning environment that encourages critical reflection growth.

Approaches to try:

- encourage open communication and actively listen to students’ worries

- show empathy and understanding towards students’ emotions

- acknowledge and appreciate students’ efforts, especially when they are struggling

- create group rules to foster classroom culture where students feel safe to ask questions, make mistakes and seek support.

Be flexible and adjust your teaching methods as needed.

Cultural protocols

This section addresses the Indigenising Curriculum Design Principles of Country and Respect, by demonstrating the importance of cultural protocols (Bunda, 2022). We focus on practical activities such as (1) undertaking a meaningful Acknowledgement of Country, and (2) reflecting on personal cultures, values and beliefs. Throughout this section we share our reflections and experiences teaching practical skills to students that can be incorporated into practice.

The course we coordinate is offered to students who are highly likely to work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities in vulnerable settings. It is therefore imperative to support students to establish effective relationships and follow cultural protocols. Adhering to cultural protocols demonstrates respect and understanding, ultimately enhancing communication, fostering trust, and building rapport between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and practitioners (Cass et al., 2002).

Investing time in learning local protocols and demonstrating genuine interest in the community is a critical step towards culturally safe practices, including fostering respectful and enduring relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities. The course explores various cultural protocols in tutorials, such as yarning circles, asset-based community development principles, the importance of self-determination for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, respecting Elders, and family and kinship dynamics. We now share two examples of how we support students to understand cultural protocols.

Acknowledgement of Country

At the beginning of each lecture and tutorial, the teaching team model an Acknowledgement of Country (Acknowledgement) that is personalised, contextual and meaningful. Do you know the difference between an Acknowledgement and a Welcome to Country? Most students don’t understand, so we dedicate time to explain the difference. An Acknowledgement can be performed by anyone as a sign of respect and gratitude to Traditional Custodians for allowing us to visit, whereas a Welcome to Country can only be performed by a Traditional Custodian of the land that you are on, often by an Elder or community leader. For example, as a Ngugi woman, Karina performs an Acknowledgement on Turrbal and Yuggera lands, because she is a visitor. On her Country, Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island), she can perform a Welcome to Country, first checking with other Traditional Custodians present in case they would like to undertake this.

In tutorials, students are supported to write respectful Acknowledgements that they then present in a safe, yarning circle environment. We support students to adapt their Acknowledgements to be appropriate to the setting and audience. For instance, in child protection or youth work settings, by acknowledging the impact of the Stolen Generations and current child protection practices. Students are encouraged to include an Acknowledgement in written assessment pieces. We provide students with written feedback on the Acknowledgement in assessments and, when requested, verbally in class.

Tip

Tip

If running this activity in your tutorials, be prepared!

Write your own Acknowledgement of Country:

- identify the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which you work/live

- name the Country (if different to the Traditional Custodians)

- acknowledge any culturally significant/sacred sites where relevant

- acknowledge Country, e.g., I acknowledge the land, waters and sky, and the interconnectedness of all living things.

Be brave and write something different to the standard Acknowledgement.

Understanding your own culture, values and beliefs

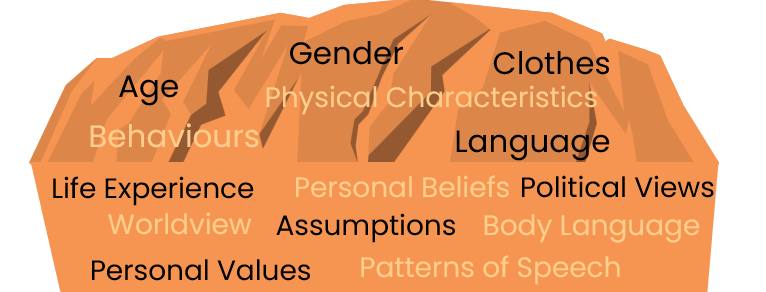

Understanding one’s own culture and values is fundamental to respecting the cultural protocols of others. To foster this understanding, students engage in a reflective activity based on Hall’s (1976) iceberg model. This activity provides a basis for students to understand Ramsden’s first step on the process to cultural safety – cultural awareness (Ramsden, 2002). Like an iceberg, much of a person’s cultural identity is hidden beneath the surface. Hall’s (1976) iceberg model highlights this concept, revealing what we see is just the tip, while the majority lies unseen below the surface. We have adapted this model to depict Uluru (see Figure 4).

The model teaches students that we cannot judge a culture based only on what we can see. Time must be taken to get to know a person’s cultures through interactions and uncover the values and beliefs that underlie the behaviour, for the person and their community. Students are encouraged to draw a diagram similar to Figure 4 and list their observable traits above the surface and hidden traits below the surface.

Students then self-reflect on the activity and what culture means to them and journal the experience guided by the critical reflection model discussed at Table 1, including aspects such as defining culture, reflecting on the ease or difficulty in defining culture, linking the above-line traits to the below-line traits, and how these aspects can influence interactions with others. Practicing the reflection model builds student confidence when addressing the self-reflection section of their assessment tasks. We then support students to understand how this activity links to cultural safety and culturally safe practice.

Tip

Tip

If you develop a similar activity for tutorials, we recommend you complete this activity yourself prior to the tutorial and again in class, alongside students, sharing your reflections of completing the activity.

Our reflections

By undertaking these activities and other similar activities in tutorials, we encourage students to embrace the course’s underlying framework of reflection, unlearning, (re)learning and planning. Reflecting on the Acknowledgement activity, we have discovered students are often reluctant and hesitant to conduct an Acknowledgement (their own, or the standard UQ version). Interestingly, many non-Indigenous students share feeling uneasy, out of fear of disrespect or wrongdoing. Through discussion and self-reflection, we unpack where this fear comes from and how to combat it, including reassuring students that the tutorial room is a safe space to practice, make mistakes and grow.

When completing the iceberg/Uluru activity, students are often surprised at the realisation that they do indeed have a culture, and more than one. Students are guided to critically reflect on previous assumptions and understandings of culture, and how these learnings impact their journeys to providing culturally safe and responsive practices.

Importance of discourse

This section explores the importance of using appropriate and respectful terminology, the impacts of deficit discourse and othering, and the importance of appropriate and respectful communication. To conclude this section, we share our reflections of teaching this content and provide insights into how you can incorporate these learnings into your practice. As outlined in Indigenising Curriculum: Consultation Green Paper (Bunda, 2022), many of the Indigenising Curriculum Design Principles are interconnected and relate to the learnings we share throughout this chapter. In the section below, we focus on the principles of Relationships, Respect and Truth. We link these principles to the impacts of discourse when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities.

Appropriate and respectful terminology

Using appropriate and respectful terminology is essential when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities, as it demonstrates a level of cultural safety and respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ identities and experiences. Through our years of teaching, we recognise the need to educate students on this topic to develop their understanding of how communication and terminology can impact an interaction. Students are introduced to UQ’s (n.d.) and Queensland Health’s (2023) terminology guidelines and then guided in their practical application. We emphasise that these documents are often developed in collaboration with local community leaders and Elders, making them a valuable resource for understanding appropriate and respectful terminology.

Since colonisation, several terms have been used to refer to, compartmentalise and describe Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities. Some of these terms have been considered offensive or inappropriate due to their colonial origins or negative connotations. For example, terms like “half-caste”, “quarter-caste” and “octaroon”, often used to describe blood quantum levels, are now widely considered offensive. It is important to instead use terms that are respectful and inclusive. See Table 2 for examples of preferred and non-preferred language/terminology.

Table 2: Preferred and non-preferred terminology, adapted from UQ’s (n.d.) and Queensland Health’s (2023) terminology guides

| Preferred terminology | Non-preferred terminology |

|---|---|

| Aboriginal peoples, Torres Strait Islander peoples, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples | Aboriginals, Islanders, 1st Nations, indigenous, aboriginal, torres strait islanders (with lowercase letters) |

| Peoples (plural) – this signifies and acknowledges the many nations and language groups across this country now known as Australia. | ATSI, A&TSI – these acronyms are often considered disrespectful as they oversimplify the diverse identities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and can be linked to historical policies with negative impacts. |

| If you are referring to both Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islander peoples, then you must use both terms. This applies to case notes, and public facing documents. | Outdated terminology, including “half-caste”, “quarter-caste”, “octaroon”. |

| If using collective terms such as Indigenous peoples, it is necessary to include a disclaimer to respectfully acknowledge the unique and distinct cultural differences of the Traditional Custodians of this country. | Language that is dismissive or disrespectful. |

| Ask people what they prefer to be called. | Making assumptions about someone’s cultural background. |

| Be mindful of the specific terminology used in different regions or communities. | Aboriginal Australian – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were here prior to these lands being called Australia. |

Tip

Tip

Table 2 is a good starting point, however, the best approach is to always ask the person their preference. For example, Kate’s grandmother prefers to be called a Gooreng Gooreng woman or a Goori (an Aboriginal person from Queensland). However, some Aboriginal people who are members of the Stolen Generations may not know their cultural connections and may prefer to be called an Aboriginal person, a Goori or a Murri (another term for an Aboriginal person from Queensland). The key takeaway is: never assume; always ask.

Deficit discourse and othering

Deficit discourse is a mode of thinking that frames and represents Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in a narrative of negativity, deficiency and failure (Fforde et al., 2013). Deficit discourse narrowly situates responsibility for problems with the people or communities affected, rather than the systems. This type of discourse is often implicated with race-based stereotypes and is an obstacle to improving health outcomes (Fogarty, Bulloch et al., 2018). Deficit discourse arises when discussions and policies intended to mitigate disadvantage become preoccupied with narratives of failure and dysfunction, thereby pathologising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities. It often permeates educational settings, perpetuating negative stereotypes and hindering authentic understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures (Fogarty, Bulloch et al., 2018). Othering language is a form of deficit discourse that involves portraying a group of people as different and/or inferior to the dominant group (Abbink & Harris, 2019; Sng et al., 2016). To foster respectful and culturally responsive teaching practices, we must challenge deficit discourse and promote a strengths-based approach that celebrates the rich histories, cultures and contributions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities.

Strengths-based approaches are a philosophical stance that emphasise the importance of focusing on a person’s, or community’s, strengths and resources, rather than on deficits and weaknesses (Fogarty, Lovell et al., 2018; Saleebey, 1996). This approach is characterised by the belief that building on existing strengths is the most effective way to work with people and communities to achieve their full potential. Strengths-based practices are actionable strategies used to implement the principles of strengths-based perspectives in real-world situations. These practices involve specific skills and techniques, including active listening, validation (recognising and acknowledging existing strengths and resources), building collaborative partnerships, and focusing on solutions. The next section outlines an activity designed to promote strengths-based approaches with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities.

Empowering students to challenge deficit discourse

We explore how we can empower students to adopt a strengths-based perspective when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities. Othering is often subtle and may involve unconscious assumptions about others (Abbink & Harris, 2019; Sng et al., 2016). Othering can manifest in various forms, including socioeconomic discrimination, ableism and appearance-based prejudice. Further, signs of othering may include attributing positive qualities to people similar to you and negative qualities to people you perceive to be different from you (Abbink & Harris, 2019; Sng et al., 2016).

In our tutorials, we present students with fictional statements that employ othering language. By working together, we develop alternative statements that emphasise strengths-based perspectives. Refer to Table 3 for illustrative examples of this activity.

Table 3: Examples of adapting discourse

| Deficit discourse example | Why this is Othering language | Strengths-based alternative | Avoiding othering |

|---|---|---|---|

| “It’s important to remember when working with the Aboriginals that they have a different communication style. They can be very reserved and speak indirectly, so you need to be patient and not expect them to be upfront about their needs.” | Generalising about Aboriginal communication styles, suggesting indirectness is inferior.

Use of ‘Aboriginals’ rather than Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people/s |

Building rapport is key when working with anyone from a cultural background different from our own. Understanding that communication styles can vary is important. Some people may prefer a more direct approach, while others may be more indirect. Being patient and allowing for open communication is essential for successful collaboration. | Focuses on cultural differences without stereotypes and emphasises adaptation for collaboration. |

| “Those Torres Strait Islander communities are so isolated; they haven’t caught up with the technological advancements of the rest of the country. They probably still live a very traditional lifestyle.” | Assuming isolation and technological backwardness for all Torres Strait Islander communities. Use of “those” and “they”. |

While some remote Torres Strait Islander communities may face challenges in accessing high-speed internet, other communities have embraced technology to strengthen cultural practices and economic opportunities. | Avoids generalisations and recognises diversity within and across communities. |

| “Working in healthcare with those Aboriginal patients can be challenging because of their weird and complex belief systems surrounding health and treatment. They don’t trust Western medicine.” | Generalising about Aboriginal beliefs and practices, and implying distrust.

Making judgements on individual belief systems. |

Working in healthcare with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients offers the opportunity to learn about rich cultural perspectives on health and healing. | Avoids generalisations and emphasises cultural safety and responsiveness. |

By engaging with these fictional scenarios, students develop critical thinking skills and learn to challenge deficit discourse, contributing to a more culturally responsive and equitable curriculum. Below, we provide insights into our reflections on students’ experiences and the impact these activities have.

Our reflections

In this section, we reflect on our experiences working with students and staff in learning about deficit discourse, strengths-based practice and perspectives, and how work in this area links to the Indigenising Curriculum Design Principles of Relationships, Respect and Truth (Bunda, 2022). Students often experience discomfort and uncertainty and have reported avoiding working with and talking about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples due to the level of fear over the repercussions of using non-preferred terminology. Some students also discuss feeling annoyed, having experienced previous lecturers and tutors who have used non-preferred terminology, which students perceived to be acceptable at the time, and now we are asking students to reconsider the use of non-preferred terminology. To combat these challenges and promote positive change, we employ the Reflect. Unlearn. (Re)Learn. Plan. model.

By addressing deficit discourse and promoting strengths-based approaches, we are demonstrating to students how we can foster respectful relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities. We are acknowledging the harm caused by historical and ongoing discrimination and working to rectify these injustices. By encouraging students to challenge harmful stereotypes and biases, we are promoting truth-telling and critical thinking. We create spaces for students to be empowered to question dominant narratives and seek out accurate and nuanced information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contemporary realities. Finally, by creating safe spaces for dialogue and learning, we are demonstrating to students how to build relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. We encourage students to understand with empathy, and practice as culturally safe and responsive health care and human services practitioners.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have explored the importance of embracing a decolonising pedagogy, characterised by reflection, unlearning, relearning and planning in a nursing, midwifery and social work context. These insights, practical and transferable across fields, are central to culturally safe practice, recognising the need for continuous learning and the power dynamics inherent in educational settings. As educators, we must strive to minimise these power differentials and create spaces for students to be empowered to engage in similar practices. It is necessary to remember that cultural safety is defined by the recipient of care, and it is applicable to everyone we work with, from service users to colleagues. Through modelling mindful language and respectful communication, we can create inclusive and empowering learning environments. As illustrated throughout this chapter, our pedagogical approach to teaching incorporates many of the Indigenising Curriculum Design Principles, including Country, Relationships, Respect, Reciprocity and Truth. Indigenising the curriculum is a collaborative process that requires engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and knowledge holders. By working together, both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous people, we can ensure that our educational practices are culturally safe and responsive.

Additional resources for teaching and research

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quality Appraisal Tool.

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) Code of Ethics.

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) Map of Indigenous Australia.

- Dadirri – Inner Deep Listening and Quiet Still Awareness(PDF, 609KB).

- Deficit Discourse and Indigenous Health: How Narrative Framings of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People are Produced in Policy (PDF, 2MB).

Additional recommendations

Additional recommendations

- For UQ staff and Higher Degree by Research students, there are 10 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Core Cultural Learning Modules available through UQ’s Workday application that we would highly recommend undertaking in their entirety.

- Show your support by attending Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander events organised by UQ.

- Attending NAIDOC celebrations at UQ or the family fun day held at Musgrave Park in South Brisbane usually on the second Friday of July each year. NAIDOC celebrations are a wonderful experience and introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures. We recommend monitoring the UQ website and the NAIDOC website (naidoc.org.au).

Reflection questions

To facilitate the practical application of the insights presented in this chapter, we offer a series of reflective questions. These questions are designed to guide people in using the models and tools discussed to Indigenise the curriculum in specific contexts. We encourage educators to consider how these approaches can be adapted to align with each unique learning environment and with student needs. These initial questions serve as a starting point, intended to stimulate ongoing discussion and reflection, and can be used in conjunction with other concepts and figures shared throughout this chapter.

- How will you incorporate cultural safety into the curriculum and your pedagogy? What challenges might you face? What supports might you require?

- How can you adapt the Acknowledgement of Country activity to your specific course context? What specific strategies will you employ to encourage meaningful engagement and understanding of Indigenous perspectives?

- What personal biases or assumptions might hinder your journey towards culturally safe practice? How can you address these to become a more culturally responsive educator?

- How can you foster a culturally safe classroom environment that values Indigenous perspectives and knowledge? What specific actions will you take to create a welcoming and inclusive space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students?

The development of these tools occurred in a nursing, midwifery and social work context. However, these questions can be effectively applied across diverse disciplines. Furthermore, these questions can be adapted to guide students in their own reflective learning journeys. Educators might consider using these questions as prompts for individual journaling, group discussions or as a framework for developing course assignments. By adapting these questions to suit their specific needs, educators can cultivate a more culturally responsive and inclusive learning environment for all students.

References

Abbink, K., & Harris, D. (2019). In-group favouritism and out-group discrimination in naturally occurring groups. PloS One, 14(9), e0221616. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221616

Bunda, T. (2022). Indigenising curriculum: Consultation green paper. Office of the Pro Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement) and Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation. The University of Queensland.

Cass, A., Lowell, A., Christie, M., Snelling, P. L., Flack, M., Marrnganyin, B., & Brown, I. (2002). Sharing the true stories: Improving communication between Aboriginal patients and healthcare workers. Medical Journal of Australia, 176(10), 466–470. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04517.x

Fforde, C., Bamblett, L., Lovett, R., Gorringe, S., & Fogarty, B. (2013). Discourse, deficit and identity: Aboriginality, the race paradigm and the language of representation in contemporary Australia. Media International Australia, 149(1), 162-173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1314900117

Fogarty, W., Bulloch, H., McDonnell, S., & Davis, M. (2018). Deficit discourse and Indigenous health: How narrative framings of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are reproduced in policy. The Lowitja Institute.

Fogarty, W., Lovell, M., Langenberg, J., & Heron, M-J. (2018). Deficit discourse and strengths-based approaches: Changing the narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing. The Lowitja Institute.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit, Oxford Polytechnic.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. Anchor Press.

Martin, K., / Mirraboopa, B. (2003). Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and Indigenist re-search. Journal of Australian Studies, 27(76), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050309387838

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2013). Towards an Australian Indigenous women’s standpoint theory: A methodological tool. Australian Feminist Studies, 28(78), 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2013.876664

Papps, E., & Ramsden, I. (1996). Cultural safety in nursing: The New Zealand experience. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 8(5), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/8.5.491

Queensland Health. (2023). Terminology guide: For the use of “First Nations” and “Aboriginal” and “Torres Strait Islander” peoples references. Queensland Government. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/147919/terminology.pdf

Ramsden, I. (1992). Teaching cultural safety. New Zealand Nursing Journal, 85(5), 21–23.

Ramsden, I. M. (2002). Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu [Doctoral dissertation]. Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington. https://tewaharoa.victoria.ac.nz/permalink/64VUW_INST/1e6vab7/alma991071664002386

Rigney, L. I. (1999). Internationalization of an Indigenous anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies: A guide to Indigenist research methodology and its principles. Wicazo Sa Review, 14(2), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.2307/1409555

Saleebey, D. (1996). The strengths perspective in social work practice: Extensions and cautions. Social Work, 41(3), 296–305. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/41.3.296

Smith, L. T. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Sng, O., Williams, K., & Neuberg, S. (2016). Evolutionary approaches to stereotyping and prejudice. In C. Sibley & F. Barlow (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the psychology of prejudice (pp. 21–46). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316161579.002

Tripcony, P. (2006). The journey and views of an Aboriginal woman. Lyceum Club Brisbane. https://www.lyceumbrisbane.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/The-journey-and-views-of-an-Aboriginal-woman-.pdf

University of Queensland, The. (n.d.). Terminology guide: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. https://www.uq.edu.au/about/files/1685/RAP_terminology%20guide.pdf