8 GenAI in Economics Education: Research Tools for Student Learning

John Raiti

How to cite this chapter:

Raiti, J. (2025). GenAI in economics education: Research tools for student learning. In R. Fitzgerald (Ed.), Inquiry in action: Using AI to reimagine learning and teaching. The University of Queensland. https://doi.org/10.14264/aa2c634

Abstract

While generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has disrupted higher education (HE), teachers are challenged to make sense of its impact on teaching and student learning. As this technology is rapidly becoming more prevalent, there is an urgency to better understand its affordances and its use by students to inform effective approaches to pedagogical practices, assessment design and academic integrity. The main objective of this qualitative study was to explore the use of ChatGPT by students in an undergraduate behavioural economics course while undertaking a written assessment task. Data was collected from a survey sent to students upon completion of the task. The survey focused on the ways the students used ChatGPT, what they found useful with this tool, and its impact on their learning. The analysis revealed that ChatGPT can be a positive disruptor that assists students with their learning. First, ChatGPT was perceived by students to be useful with developing the various components of a written assessment task. Second, students did not perceive ChatGPT as replacing their learning. Third, teacher reflection highlighted the importance of teaching practices that have a deliberate focus on viewing and scaffolding the learning process leading to the submission of the final written assessment task. The findings suggest that a focus on providing teachers with ongoing professional learning and support for assessment design and complementary pedagogical approaches is imperative in HE as GenAI continues to evolve at a rapid pace.

Keywords

Generative Artificial Intelligence, Economics Education, Authentic Assessment, Student Learning, AI Literacy, Higher Education Pedagogy

Practitioner Notes

- Design assessment tasks that explicitly mirror real-world practice to engage students in authentic applications of theory.

- Introduce GenAI literacy early in the course through scaffolded tutorials that model responsible and critical use.

- Shift the assessment focus from product to process, providing ongoing feedback and visibility into how students learn.

- Encourage reflection and peer discussion on how AI outputs compare with human reasoning to build evaluative judgement.

- Support educators through professional learning communities that share strategies for integrating GenAI ethically and effectively.

Introduction

This case study focuses on the use of ChatGPT by students to undertake a written assessment task in an undergraduate economics course during Semester One 2023. Underpinned by the principles and benefits of authentic assessment (Villarroel et al., 2018), students were asked to develop an original research project in a behavioural economics course. The intention of this task was to mirror the type of “real world” work that economists undertake in consultancies, corporations and governments while equipping students with future-ready skills. The task was introduced in the year prior (2022) to address the lack of authentic assessment in the course. Prior to 2022 the course assessment relied heavily on exams, quizzes and worksheets. Overall, the pedagogy for this task (and the course) focused on “assessment for learning” (Liu and Bridgeman, 2023). (Information of implementation of this assessment task is also outlined in the UQ Assessment Ideas Factory).

Specifically, the task involved writing a research proposal in which students demonstrate their ability to apply behavioural economics theory to a real-world situation. The aim of the task was also to provide students with an opportunity to develop their skills with research and communicating economic thinking. In doing so, students were permitted to use GenAI tools such as ChatGPT to develop their research proposals. This enhanced the authenticity of the task (Powell et al., 2024) enabling students to use this technology in a meaningful way for understanding its use and potential in their future careers (Upsher et al., 2024). The construction of the task’s authenticity also aligns with recent research in economics education. This indicates that ChatGPT can easily provide answers to numeric-based and text-based questions in economics at the lower levels of Bloom’s taxonomy (“remember”, “understand”) (The University of Queensland, n.d.) and perform relatively well at the medium levels (“apply”, “analyse” and “evaluate”) (Thanh et.al., 2023). However, ChatGPT does not excel at handling text-based questions at the highest level of Bloom’s taxonomy (“create”) in GenAI-integrated tasks as it does not construct arguments coherently and provide relevant references (Thanh et.al., 2023). Hence, this task was deliberately designed so that students demonstrated their skills at the highest level of Bloom’s taxonomy (“create”) by constructing and developing a new original work (research proposal).

Using the Technology Pedagogy and Content Knowledge (TPACK) model (Mishra & Koehler, 2006), the goal is to better understand the interplay between GenAI technologies, the delivery of the content (in this instance, behavioural economics theory) and the pedagogical approaches to support and enhance learning. Traditionally, economics pedagogy has primarily adopted a teacher-centred approach mainly through lectures (Sekwena, 2023). However, teachers are beginning to adopt more active learning strategies to enhance student engagement. The emergence of GenAI affordances that differ significantly to other digital technologies, changes our relationship with content and has implications for teaching practices. Hence, to better understand the dynamic relationship between the content, the pedagogical approach and the technology, this case study aims to answer the following research questions.

- How and to what extent do students use GenAI tools for undertaking written research assessment tasks?

- What are implications of using GenAI tools for teaching practices?

- What do teachers need to know to integrate GenAI effectively?

To this end, this case study makes contributions to a growing discourse. Firstly, it contributes to the discourse on the integration of GenAI in economics education and HE. Secondly, it contributes to understanding student adoption and motivation to use GenAI. Thirdly, it contributes to the emerging repository of pedagogical practices and knowledge for teachers to draw upon with integrating GenAI effectively and meaningfully in HE classroom settings.

Literature Review

The teaching of economics in HE is generally viewed as “traditional” with lectures being the natural and predominant mode of delivery and approach (Sekwena, 2023; Volpe, 2015). Scholarly literature points out that limited focus was placed on the importance of pedagogical practices until the end of the 20th century when active learning became recognised as a better approach to teaching of economics (Becker, 2000) and for preparing students to “think like an economist” (Ray, 2018). This approach emphasised transforming and challenging the notion of students as passive learners to becoming more active by critically analysing and solving real-world problem using economic theory (Ray, 2018).

The use of “cases” then emerged as a “new” pedagogical approach and manifestation of active learning (Becker et.al., 2006; Ray, 2018; Volpe, 2015), which bridged a perceived gap between the traditional study of economics and its application in the real world (Ray, 2018; Puhringer & Bauerle, 2019; Volpe, 2015). Already well established in other traditional discipline areas such as law and medicine, the “case method” was introduced to economics to motivate students by applying theory to narrative accounts of real-world scenarios (Ray, 2018; Volpe, 2015). This was perceived as providing the pedagogical benefits of engaging students in classes (Becker et.al., 2006) and extending students beyond “problem sets” which are a traditional staple task in economics (Becker et.al., 2006; Ray, 2018; Volpe, 2015). Whereas problem sets have a single correct answer, cases enhanced student learning and achievement by asking them to make sense of a complex series of events in the same way they transpire in the real-world scenarios (Ray, 2018; Volpe, 2015). These scenarios required students to simulate the rigorous decision-making processes to develop and justify their answer (Ray, 2018). Given the complexity of these scenarios, there is no single right answer in cases (Ray, 2018; Volpe, 2015). In doing so, working through cases was seen as effective for developing the essential proficiencies required by economists in their real-world work (e.g. critical thinking skills, communication skills, collaboration with teams) (Volpe, 2015).

Whilst economics academics and teachers continue shifting to practices that promote active and authentic learning, they have also recognised the importance of innovating new pedagogical approaches to address the disruption of GenAI (Suleymenova et. al., 2024). The scholarly literature that emerged across the sector after OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT in November 2022 focused on academic integrity. Though ChatGPT and GenAI more broadly offer potential practical benefits and opportunities for enhancing student learning (Cotton et.al., 2023) and innovation (e.g. create content, assessment design, personalised learning), the predominant discourse amongst educators and administrators when this technology emerged centred around cheating and plagiarism (Sullivan et al., 2023). Surveys indicate that one in three university students have used AI to cheat on assignments, and most report being tempted to do so (Sullivan et al., 2023). Further, this discourse outlined concerns that use of ChatGPT and GenAI can result in students not developing the skills for critical thinking and communication and verifying information (Iqbal et al., 2023; Rowsell, 2025; Willems, 2023). However, these concerns stem from a limited understanding of the affordances of GenAI tools which are significantly different to previous technologies (Mishra et al., 2023).

Despite the growing concerns, little was known known about the preferences and choices of students in the first year after ChatGPT’s release. A body of literature has now emerged drawing on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM; Granić, 2022) and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT; Strzelecki, 2024) as theoretical foundations for understanding the perceived usefulness, effort and enjoyment of using ChatGPT and how this influences student behaviour. A survey of students at four Australian universities indicates that students perceive GenAI to be useful in their studies including for answering questions, creating written text and analysing documents and data (Chung et. al., 2024). However, given that GenAI tools are freely available, there have been only a handful to studies to date on whether students are adopting such tools and in what way (Smerdon, 2024).

Additionally, at the time of ChatGPT’s release there was generally little known in the literature about the pedagogical considerations to make best use of these technologies to enhance student learning. GenAI was initially perceived by teachers as being untrustworthy with many still to be persuaded as to its value (Newell et.al., 2024). This has contributed to the pre-dominant discourse of academic integrity, cheating and plagiarism (Mishra et al., 2023) with educators calling for a return to traditional exams to ensure assessment security (Saunders et at., 2024). Hence pedagogy was being informed by a deficit model of academic dishonesty (Newell et.al., 2024).

Some literature is now emerging that suggests how best to situate the use of GenAI in teaching and assessment pedagogical practices. Within this, two main themes emerging are (1) practices as to how non-invigilated authentic assessment tasks are implemented to enhance authentic learning and ensure academic integrity, and (2) the need to integrate GenAI literacy in HE courses and programs for all disciplines. Both themes are not exclusive as they have a symbiotic relationship that is mutually beneficial to enhancing learning.

(1) Assessment to enhance learning and academic integrity

The literature points to focusing first on the “technology” in the TPACK model (Mishra & Koehler, 2006) to understand the unique affordances of GenAI, which differ to other digital technologies and how this will change teacher knowledge and practice (Mishra et. al., 2023). In simple terms, whereas search engines retrieve information from existing web pages or databases, GenAI tools generate data (text, images, code) by using models which are trained on identifying and mimicking patterns in large datasets using natural (human) language (Farrelly & Baker, 2023; Mishra et. al., 2023). Hence, creating new knowledge is no longer the sole domain of discipline experts as it can be generated by prompting which is open to all learners (Rivers & Holland, 2023). This in turn changes how content is considered and consequently the approaches which are appropriate for effective integration in teaching and learning (Mishra et. al., 2023).

From forming a better understanding of GenAI technologies and how content is reconsidered, literature has subsequently emerged which focuses directly on pedagogy to enhance learning whilst ensuring academic integrity. The main emphasis in the literature is on the “process” of developmental learning demonstrated by students, while undertaking authentic assessment tasks, rather than relying only on the final artefact or “product” that is submitted (Lodge, 2024). Assessing “process” over “product” represents a paradigm shift in HE teaching practices, including economics (Sekwena, 2023), as it is widely recognised that greater attention is given to the output and outcomes of assessment with little attention given to understanding learning processes (Lodge & Ashford-Rowe, 2024). Thus, the neglect of the learning process coupled with GenAI tools that can produce artefacts, have created vulnerabilities for HE assessment (Lodge & Ashford-Rowe, 2024). However, teaching practices which focus on the process for how students created the final artefact provides teachers with at least some visibility (Sherwood & Raiti, 2024; Smith et al., 2024). Concurrently, the literature also emphasises “assessment for learning” as a pedagogical approach for authentic assessment (Liu, & Bridgeman, 2023). Here, students use GenAI as tools to enhance productivity (e.g. generating ideas, summarise sources) but more importantly they demonstrate learning by articulating how they use these tools in their thought processes to develop solutions to authentic problems (Liu, & Bridgeman, 2023). In doing so, providing students with on-going feedback and support throughout the learning process (not only for the final product) is positioned as a fundamental and integral component to validate assessment integrity.

Within the context of teaching economics, the literature points out a greater focus on higher-order cognitive processes and thinking skills in learning as a safeguard for academic integrity. Constructing and re-orientating numeric and text-based questions that reflect the higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy is seen by economics educators as a strategy for addressing potential misconduct (Suleymenova et. al., 2024; Thanh et.al., 2023). At the same time, economics educators see the need for written responses (e.g. essays) to be re-designed to be fit for purpose in a changing digitally driven environment (Suleymenova et. al., 2024). Whilst there has been commentary in popular media headlining the “death of the essay”, economics educators value the critical thinking required in essays and recognise that exploring alternative assessment methods and innovative pedagogies are imperative (Suleymenova et. al., 2024).

AI literacy

The focus on the learning process has naturally led to the importance for ensuring students have the skills and literacy to use GenAI tools critically, ethically and responsibly. The introduction of GenAI literacy programs is viewed as an extension of the various literacies (e.g. data, digital, information, media) that students are expected to demonstrate (Chan & Colloton, 2024). Subsequently various GenAI literacy frameworks have been developed and proposed which generally focus on understanding the uniqueness of the technology, how it is applied as a complementary tool for learning, and its ethical use (Farrelly & Baker, 2023). In economics, there is consensus that a commitment is needed to develop and introduce economics-focused Gen-AI skill sets as these are essential for enhancing education in the discipline (Suleymenova et al., 2024).

Methods and Methodology

This research focuses on a second-year undergraduate economics course (187 students) at The University of Queensland. In Semester 1, 2023, students were asked to develop an original research project in which they apply behavioural economics theory to a real-world situation. The task has eight components for students to complete (research topic, title, abstract, introduction, literature, method, conclusion, references). The full assessment task is included in Appendix F – Research Proposal Instructions for Students. Students could freely use GenAI tools for any component.

The tutorials to support students with this task focused on active learning activities. This included activities dedicated to developing students’ GenAI literacy in the weeks leading up to this task. For example, students were asked to generate and critique the output from ChatGPT by comparing responses to answers given provided by the course coordinator. The students were then guided by the course coordinator and tutors in activities which focused on understanding the biases in behavioural economics in the output generated by ChatGPT. Further, the course coordinator and tutors showed students specific examples of the use of ChatGPT for academic research.

Pedagogically, there was also a deliberate focus on the learning process undertaken by students in the weeks leading to the final submission. The weekly tutorials were designed to be “workshops” in which students showed their work in progress. This enabled the course coordinator and tutors to provide on-going feedback which in turn allowed students to continually improve their research proposal. As part of this, students were asked to present a “2-minute pitch” (formative assessment) during this process for which they received peer and tutor feedback. Essentially, emphasis was placed on students’ continual reflection of their work through continuous evaluation (e.g. regular check-ins) and reflection on their learning processes with the feedback used to encourage further iterations (Smith et. al., 2024). This also provided the course coordinator and tutors visibility of the process undertaken by each student to develop their research proposal.

After their research proposals were submitted and marked, the students were sent a survey which asked whether they used GenAI tools for any component in the task[1]. The survey was coded in Qualtrics. See Appendix G – Survey. If students answered “yes”, they were then asked to indicate which components they used GenAI tools. If students answered “no”, they would then be asked to give their reasons. 69 students (out of 187 in the course) completed the survey, a 37% response rate.

Results

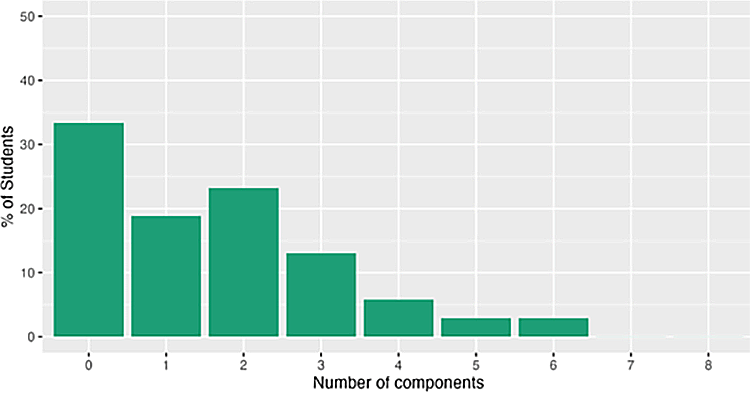

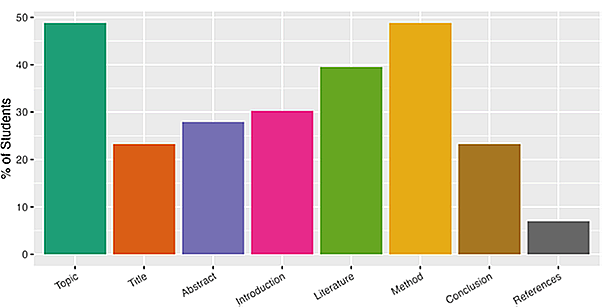

The results show that two-thirds of respondents (N=46) used GenAI tools for their research proposal. The median number of components for which students use GenAI tools was only 2 out of 8 (See Figure 1). Further, GenAI tools were used for generating the research topic and for writing the method which are the two most heavily components in the marking rubric (see Figure 2).

Figure 1

Note. From ‘Fig. 1. Student AI Usage’ in “AI in essay-based assessment: Student adoption, usage, and performance,” by David Smerdon, 2024, Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100288. Shared under a Creative Commons – Attribution 4.0 licence.

Figure 2

Note. From ‘Fig. 1. Student AI Usage’ in “AI in essay-based assessment: Student adoption, usage, and performance,” by David Smerdon, 2024, Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100288. Shared under a Creative Commons – Attribution 4.0 licence.

A thematic analysis of the open-ended responses identified six themes – idea generation, writing and structuring assistance, literature search and reference assistance, grammar and error checking, statistical and data analysis assistance, and the overall impact on learning (Smerdon, 2024).

Table 1

| Theme | Number of Responses |

|---|---|

|

Idea generation and brainstorming |

14 |

|

Writing and structuring assistance |

12 |

|

Literature search and reference assistance |

11 |

|

Grammar and error checking |

4 |

|

Statistical and data analysis assistance |

8 |

|

Overall usefulness and learning impact |

9 |

Note. From ‘Table 5: Frequency of themes’ (Appendix A: Supplementary data) in “AI in essay-based assessment: Student adoption, usage, and performance,” by David Smerdon, 2024, Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100288. Shared under a Creative Commons – Attribution 4.0 licence.

Additional methodological details supporting the thematic analysis can be found in Smerdon’s (2024) paper.

Reflection

Below are illustrative quotes from the student feedback for each theme as documented in Smerdon’s (2024) paper. Each student has a unique identifier.

Idea generation and brainstorming

“I found ChatGPT useful to provide a starting point for this assessment. I used it for coming up with basic ideas, so I was then able to expand upon these.” (S3)

“I used ChatGPT mainly for brainstorming and also workshopping my research idea.” (S11)

(Smerdon, 2024)

Writing and structuring assistance

“I used ChatGPT to help understand how I should structure my method section. I also used it when going through journal articles as a time saver by asking it to simplify and summarise what the article was testing.” (S10)

“ChatGPT helped me structure my research proposal and ensure coherence in my writing.” (S9)

(Smerdon, 2024)

Literature search and reference assistance

“I used ChatGPT only for idea generation and directing me to obscure references when I was having trouble finding appropriate articles.” (S12)

“ChatGPT assisted me in finding relevant literature, although some suggestions were not reliable.” (S2)

(Smerdon, 2024)

Grammar and error checking

“ChatGPT was useful in identifying grammatical mistakes, but it was very bad/useless in generating “good” ideas as they were all very basic.” (S1)

“I used ChatGPT mostly as a Grammarly type tool to restructure my sentences and make them more concise.” (S9)

(Smerdon, 2024)

Statistical and data analysis assistance

“ChatGPT can effectively help me propose corresponding detections based on the intelligence and data I have collected, such as t-testing, binomial distribution testing, and chi square testing.” (S6)

“I used ChatGPT to recommend a method of statistical analysis for my project, as it seemed a necessary inclusion but something I had not been taught during the course.” (S15)

(Smerdon, 2024)

Overall usefulness and learning impact

“I believe it had no effect on my learning. ChatGPT could potentially help generate ideas, and even write the whole proposal, but it will be extremely poor, basic and lacking everything we learnt in class.” (S22)

“ChatGPT greatly reduced the time I spent in the initial stages of planning and researching.” (S23)

“ChatGPT was very helpful for brainstorming and structuring my proposal, but I still had to do most of the work myself. Overall, I would have learned less without it.” (S24)

(Smerdon, 2024)

Overall, the feedback from students indicates that ChatGPT was perceived to be a useful tool assisting with developing the six components in the research proposal task. Importantly, the students indicated that ChatGPT did not replace learning.

Teaching Practices

On reflection, this task highlighted that importance of assessment and technological tools being fully integrated into teaching practices. Using the TPACK model, introducing new and unique technology like GenAI changes how content is considered and consequently how this is delivered and how we think about teaching practices to enhance learning. Firstly, it highlighted that there are new foundational literacies and skills which need to be taught and developed by students. The focus on developing GenAI literacy in tutorials is an essential starting point. Secondly, the content that can be easily generated by GenAI changes the way assessment tasks are implemented. Shifting the assessment focus from the final submission (assessment of learning) to a developmental learning process (assessment for learning) is critical.

Future Directions

More data were collected in the same undergraduate course in 2024, and further data will be collected in 2025, expanding the sample to postgraduate students. This is to (a) better understand the impact across diverse student groups, and (b) observe how the effects change over time as GenAI tools improve. In addition, it is intended to conduct a focus group of students in the 2025 and later cohorts of this course. Further, replication of this case study in other courses and programs would also help understanding of best practices for integrating AI in authentic assessment tasks. As GenAI continues to evolve, it will be useful to compare the findings of this case study during the introduction of ChatGPT in 2023 to 2025 to courses at a later stage identifying similarities and differences.

It is intended to use the findings and insights of this case study to contribute to the discourse on AI literacy in economics education. Whilst this discourse has now emerged in broad terms in HE, it is unclear how AI literacy applies to the discipline of economics. Specifically, it is unclear how “economics-focused Gen-AI skill sets” are developed and taught to prepare students to be successful in their future careers as economists. This needs to be defined and clarified by economics educators. Hence, it is intended that this case study, and the teaching and re-design of assessment in other economics courses, are a starting point for a focused discussion on AI literacy. Further, this case study can be a starting point for economics educators to establish discipline-specific communities of practice which determine and develop the pedagogical practices required for “new” GenAI-integrated learning environments.

More broadly, it is also intended for this ongoing work to inform not only teaching and assessment practices but also wider stakeholders at both local and systemic levels. A focus on providing teachers with resourcing for ongoing professional learning and the pedagogical support, and opportunities for sharing practices, is imperative as GenAI continues to evolve at a rapid pace.

Acknowledgement

The author gratefully acknowledges Dr David Smerdon for the design of the Research Proposal assessment task in this case study and the subsequent research on how students used ChatGPT for the various components in the task. David’s research has not only informed this case study but also contributes to the discourse on best practices for integrating GenAI in economics education and more broadly in HE.

References

Becker, W. E. (2000). Teaching economics in the 21st Century. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(1), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.14.1.109

Becker, W. E., Becker, S. R., & Watts, M. W. (2006). Teaching economics : More alternatives to chalk and talk. Edward Elgar Pub.

Chan, C. K. Y., & Colloton, T. (2024). AI Literacy. In Generative AI in Higher Education (Vol. 1, pp. 24–43). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003459026-2

Chung, J., Henderson, M., Pepperell, N., Slade, C., & Liang, Y. (2024). Student perspectives on AI in higher education: Student survey. Monash University. Standard. https://doi.org/10.26180/27915930.v1

Cotton, D. R. E., Cotton, P. A., & Shipway, J. R. (2023). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education & Teaching International, 61(2), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2190148

Farrelly, T., & Baker, N. (2023). Generative Artificial Intelligence: Implications and Considerations for Higher Education Practice. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111109

Granić, A. (2022). Educational technology adoption: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies, 27(7), 9725-9744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10951-7

Iqbal, N., Ahmed, H., & Azhar, K. (2023). Exploring teachers’ attitudes towards using ChatGPT. Global Journal for Management and Administrative Sciences, 3(4). 10.46568/gjmas.v3i4.163

Liu, D., & Bridgeman, A. (2023) What to do about assessments if we can’t out-design or out-run AI? https://educational-innovation.sydney.edu.au/teaching@sydney/what-to-do-about-assessments-if-we-cant-out-design-or-out-run-ai/

Lodge, J., & Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. (2024). The evolving risk to academic integrity posed by generative artificial intelligence: Options for immediate action. https://www.teqsa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-08/evolving-risk-to-academic-integrity-posed-by-generative-artificial-intelligence.pdf

Lodge, J. M., & Ashford-Rowe, K. (2024). Intensive modes of study and the need to focus on the process of learning in higher education. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 21(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.21.2.02

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

Mishra, P., Warr, M., & Islam, R. (2023). TPACK in the age of ChatGPT and generative AI. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 39(4), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2023.2247480

Newell, S., Fitzgerald, R., Hall, K., Mills, J., Beynen, T., May, I. C. S., Mason, J., Lai, E. (2024). Integrating GenAI in higher education: Insights, perceptions, and a taxonomy of practice. In S. Beckingham, J. Lawrence, S. Powell, & P. Hartley (Eds.), Using Generative AI Effectively in Higher Education (pp. 42–53). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003482918-7

Powell, S., & Forsyth, R. (2024). Generative AI and the implications for authentic assessment. In S. Beckingham, J. Lawrence, S. Powell, & P. Hartley (Eds.), Using Generative AI Effectively in Higher Education (pp. 97–105). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003482918-15

Puhringer, S., & Bauerle, L. (2019). What economics education is missing: the real world. International Journal of Social Economics, 46(8), 977–991. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-04-2018-0221

Ray, M. (2018). Teaching economics using ‘Cases’ – Going beyond the ‘Chalk-And-Talk’ method. International Review of Economics Education, 27, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2017.12.001

Rivers, C. and Holland, A. (2023, August 30). How can generative AI intersect with Bloom’s taxonomy? Times Higher Education. www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/how-can-generative-ai-intersect-blooms-taxonomy

Rowsell, J. (2025, January 17). Academics ‘fear students becoming too reliant on AI tools’. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/academics-fear-students-becoming-too-reliant-ai-tools

Saunders, S., Coulby, C., Lindsay, R., Hartley, P., Lawrence, J., Powell, S., & Beckingham, S. (2024). Pedagogy and policy in a brave new world: A case study on the development of generative AI literacy at the University of Liverpool. In Using Generative AI Effectively in Higher Education (pp. 11–20). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003482918-3

Sekwena, G. L. (2023). Active learning pedagogy for enriching economics students’ higher order thinking skills. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.22.3.15

Sherwood, C., & Raiti, J. (2024, August 1). Connecting adult learning principles, assessment and academic integrity. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/connecting-adult-learning-principles-assessment-and-academic-integrity

Smerdon, D. (2024). AI in essay-based assessment: Student adoption, usage, and performance. Computers and Education. Artificial Intelligence, 7, 100288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100288

Smith, D., Francis, N., Hartley, P., Lawrence, J., Powell, S., & Beckingham, S. (2024). Process not product in the written assessment. In Using Generative AI Effectively in Higher Education (1st ed., pp. 115–126). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003482918-17

Strzelecki, A. (2024). Students’ acceptance of ChatGPT in higher education: An extended unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Innovative Higher Education, 49(2), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-023-09686-1

Suleymenova, K., Dawood, M., & Psyllou, M. (2024). Essays in economics in ICU: Resuscitate or pull the plug? International Review of Economics Education, 45, 100284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2024.100284

Sullivan, M. (2023). ChatGPT in higher education: Considerations for academic integrity and student learning. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(1), 31-40. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2023.6.1.17

Thanh, B. N., Vo, D. T. H., Nhat, M. N., Pham, T. T. T., Trung, H. T., & Zuan, S. H. (2023). Race with the machines: Assessing the capability of generative AI in solving authentic assessments. Australasian Journal Of Educational Technology, 39(5), 59–81. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.8902

Upsher, R., Heard, C., Yalcintas, S., Pearson, J., Findon, J., Hartley, P., Lawrence, J., Powell, S., & Beckingham, S. (2024). Embracing generative AI in authentic assessment: Challenges, ethics, and opportunities. In Using Generative AI Effectively in Higher Education (pp. 106–114). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003482918-16

The University of Queensland, (n.d). Behavioural Economics Research Proposal. UQ Assessment Ideas Factory. https://aif.itali.uq.edu.au/node/behavioural-economics-research-proposal

The University of Queensland. (n.d.). Structuring learning. https://itali.uq.edu.au/teaching-guidance/principles-learning/guiding-theories-and-frameworks/structuring-learning

Villarroel, V., Bloxham, S., Bruna, D., Bruna, C., & Herrera-Seda, C. (2018). Authentic assessment: Creating a blueprint for course design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(5), 840–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396.

Volpe, G. (2015). Case teaching in economics: History, practice and evidence. Cogent Economics & Finance, 3(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977

Willems, J. (2023). ChatGPT at universities – The least of our concerns. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4334162

- This study received ethics approval from The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (BEL LNR Panel), project number 2024/HE001346: AI Inquiry-Led Teaching Innovation. ↵