3 Leading with Responsible AI – The Case for Ethical Human Learning

Melinda Pratt and Iris Zhang

How to cite this chapter:

Pratt, M. & Zhang, I. (2025). Leading with responsible AI – The case for ethical human learning. In R. Fitzgerald (Ed.), Inquiry in action: Using AI to reimagine learning and teaching. The University of Queensland. https://doi.org/10.14264/da08317

Abstract

This case study examines the ethical and pedagogical dimensions of leading with responsible AI in undergraduate learning, focusing on how students’ creative and interpretive processes unfold when artificial intelligence is introduced as a co-participant in learning. Situated within a first-year education and creative inquiry context at The University of Queensland, the study compares two learning environments: the Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) program at the UQ Art Museum and an integrative AI-assisted collaborative project. Drawing on Graham Wallas’s illumination phase of the creative process, the research highlights how pedagogical attention, the deliberate focus on students’ internal and external processes of meaning-making supports ethical, reflective, and socially aware learning. Through iterative, co-led experiences, students learned to distinguish between human and automated creativity, demonstrating the importance of inner attentiveness, aesthetic sensitivity, and embodied ethical reasoning. The study concludes that responsible AI pedagogy requires careful orchestration of both technological and human capacities, emphasising experiential, ethical, and creative engagement as the foundation for leadership and civic readiness in the intelligence era.

Keywords

Responsible AI, Creative Process, Ethical Learning, Visual Thinking Strategies, Co-led Learning, Generative AI, Human-Centred Pedagogy

Practitioner Notes

- Frame AI tools as prompts for reflection and dialogue, pairing them with explicitly human acts (silence, observation, peer sense-making).

- Build in moments of deliberate pause and verification (e.g., VTS-style prompts: What’s going on? What makes you say that? What more can you find?) to surface ethical reasoning and depth.

- Sequence activities to move from pre-personal reflection (private notes) to extra-personal articulation (public critique), then require evidence-informed revision.

- Scaffold prompting alongside source-checking, bias scans, and short rationale statements that explain what was accepted, altered, or rejected.

- Evaluate the chain of attention (reflection logs, peer responses, revisions) and make ethical judgement, not AI output quality, the centre of criteria.

Introduction

This case study is about co-led pedagogical processes, and communicable realities, in an undergraduate learning context that also includes artificial intelligence (AI). With the transition into the ‘Intelligence Era’ (Webb & Jordan, 2024) in a global society, there has been little attention given to how AI intersects with student creativity and processes. Being a merger of human realities and assistive algorithmic intelligence, this invention is hard to fathom beyond the self-corrective and generative functions it performs. Automated intelligence platforms are among the many information efficiencies introduced to assist humans in pursuit of progressing societal development. Since the release in early 2025 of the open-source AI platform “Deep Seek’ in China, it has been striking how frequently global media highlight leaders and educators grappling with what AI asks of us as responsible humans (Fitzgerald & Curtis, 2025). The growing interest in AI assistive technology centres on the impact of automated information, raising questions about how developers can ensure its responsible human application. In Amazon’s CEO Andy Jassy’s leadership on AI, reinvention, and corporate culture, he offers clues on the stakes about the real work of humans in conjunction with AI, through his responsible focus in tracking effects from human development, and to experience, for societal good (Jassy, 2025). Yet in current AI scholarship, studies attend to tracking the generative platform experience as a productive prioritisation tool and profit-driven techniques (Black & van Esch, 2020; Chubb et al., 2022; Chui et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2022). For decades, it has been tangible to see focus shifting from human development in learning, to ‘tech’ – plus skills, plus jobs, and plus data. When a first-year higher education student cohort (n = 93) began to articulate their developing stance towards learning, what emerged were the communicable realities, co-led pedagogically, and created in modulative configurations, that surfaced creative attainments in learning, and as ethical to fundamental internal processes required to process information in novel ways.

Part of the attention had to do with two central questions of creative matters: what supports undergraduate students’ creative processes, where AI platforms are introduced? Why is ethical responsiveness in co-led creative processes pedagogical, in leading one another, and initiating learning process? Inquiring about responsible co-leading requires addressing what bio-semiotician, Joseph Hoffmeyer, scientifically introduced on the grounds of natural process – the counterintuitive claim that intelligent machines fail at the point where they “converse with us” (p.176). In his research, Hoffmeyer argued that the confusion arises from human experience itself, which guides how the interpretation process combines in relation to the body’s needs and purposes (Hoffmeyer, 1998). For example, receptive sensing, which manifests an internal awareness, and indicates association trains, that brings a flash of success of interpretation (Sadler-Smith, 2015). Yet in current societal approaches to student learning, the human ‘inner stages and creative lenses’ are often overlooked in learning, even though essentially neurobiological. That is to say, the internal process and organising effects students are individuating (Marais et al., 2024). For human intelligence exists not just proxy for mental recognition. It is the human nature of bodily sensory activities in matters of creativity itself. As AI function infiltrates every known aspect in daily life, the physical human ‘mental success out of sense recognition’ remains distinct from AI capability. The agenda of technological development, when juxtaposed with human experience, forces us to confront this ecological imbalance through a focus on the ethics, of sensory human means, of which underpin the students experience explored in this case study.

We understand the experiences students engaged in this project were social in nature between private creativity processes and public sharing of one’s own subjective human experience. To honour student dignity in this process invited us to consider the sources of attention and realities communicated in various modalities by students. We also considered our own attention to student responses towards an examination of what sources of aesthetic function and selective forces that arose and students responded to throughout. In doing so, student responses revealed ways to recognise the distinctive constructed social reality and emerging learning stance being formed, as part of student attention in the creative learning process (Ashcraft, 2021). With the objective of student learning of co-leading creative processes that prepare students as responsible educators, sensory aspects in pedagogical attention provided fertile insights for ‘the selective force’ in interpretations and differing sources that illuminate human learning.

At the start of the course roll-out and AI project, discussions in the staff-student partnership were focussed on the course objectives of relevance as it secured the purposeful opportunity in content topics and student experiential contexts. Two relevant project experiences were headlined as comparable platforms for focusing on student interpretation processes. These projects featured the three-staged course-embedded exhibition of Visual Thinking Strategies at The University of Queensland Art Museum and afterwards a mid-course integrative AI and peer collaborative ‘exhibition’. Both experiences allowed students self-corrective and generative verbalised activation within visual platforms. To co-lead the student experiences of interpretation, of creativity, considered the naturally internal processes of the human inner-stage processes itself. We clarified the purpose of the research based on the course construct of pedagogical attention and communicable realities. This case study approach sets the scene that deliberately targets Graham Wallas’ illumination phase of a mid-creative process, accompanied by the experiential means in platforms, raising trains of associations, and motility of deep effectual learning engaged by students.

Here, Hoffmeyer sees experience as essential “we do not get anywhere if we do not understand each other” (p. XVII). This highlights the importance of recognising students as active subjects positioned in pursuit of self-leadership for a global society (Pless et al., 2011). He further argues that in a learning context, an aesthetic staging of information risks neglecting the deeper value of experiential engagement, where in a natural real sense learners shape their own creative existence in constructing new perspectives on self and the world (Hoffmeyer, 2018). Perhaps the enduring didactic staged transmissions to information delivered and in respect to traditional higher education are not staged information at all but the attentional activations, yet when the learning starts in topic content, it moves students to other realities, including the potentials of human needs, to erase internal creative process. To lead responsibly for deep experiential engagement in pedagogical missions, this matters. Paying attention to what students engage particularly in relation to AI-generated information vis-à-vis other pedagogical trajectories in order to ask why the formulate-response relationships affirm internal awareness in processes of creativity in the act of learning itself.

To recap, the basis of pedagogical attention exists through experiential contexts and creative process in co-leading realities, and which posits the student into interpretative ‘reasons’ for learning. Through this juxtaposition of thought, as associative creations, in the Visual Thinking Art Museum session and a physical AI exhibition project, students attended to observe, evaluate, synthesise, justify and speculate. The physical AI project signals how students orientated modulations so to reach towards visual thinking – as creative accumulations – which provides comparable, but also different internal experiential sequences. These parallel student considerations show the depth of attention varies between the illumination of visual thinking. These first-year students were engaged in visual thinking through attention on societal issues and challenges in course content but were asked to draw upon non-obvious scenarios outside their experience to engage sensorial wrought-learning. Students are entering a society where frequently ethical dilemmas warrant their attention as they encounter ambiguity. Learning through constructive means that initiate strong emotion and configuring responses becomes an individuated bodily response, which embeds such attention throughout the pedagogical experiences. This purpose offers a clear foundation to compare student leading that coheres in the content, context, and information generated by both the UQ Art Museum and Integrative AI Project platforms. Each platform assists students who are in a constant state of engaging creative processes to contend with suitable responses for improved awareness, and for enhanced self-leading of more responsible leaders in society.

Pedagogical Attention as a Creative Process

What could be considered pedagogical attention is one question in the literature, but student communicable realities open the dimension more broadly: of kinds of developmental activities in the learning experience (Shotter, 2009). It is conducive to begin a discussion about learning in the recent increased focus on pedagogical attention (that builds intellectual awareness) and illumination (interlinking existing knowledge with prescient observations). In the ‘Art of Thought’ written by Graham Wallas (1926), the economist and schoolmaster identified a creative process model, which Sadler (2015) extended recently, that surface five scientific explanations for interpretative steps, of which holds relevance still today. The living body fundamentally self-creates in ‘striving to survive’ and naturally sustains biological forces and active movement, but also utmost central to human development (Hoffmeyer, 2008). Of all the human form, attention comes in creative processes to forcefully ‘spread’ the modulated body to draw from external registrations and internal feelings to overcome environmental obstacles. This activation of thought is made in Wallas’ creative phases, who questions artificial outsourcing of this intelligence (Sadler-Smith, 2007).

Phases of creative processes have been considered as a pedagogical matter to invoke a student response, and amenable when novel associations are combined. In this chapter, creativity is treated as a pedagogical practice that invites thoughtful student response. The analysis centres on the illumination and verification phases of the creative cycle, where students move from initial insight to tested understanding and how external engagement enables them to co-lead their learning and articulate personal positions. Rather than equating learning with attention alone, students are framed as receptive, living systems that communicate meaning through interaction with people, materials, and place. In AI-rich courses this stance matters, because an exclusive reliance on synthetic information can crowd out attention to the human and internal processes that give learning consequence. We argue that creative processes cultivate self-organisation and shared sense-making, laying foundations for leadership and civic participation.

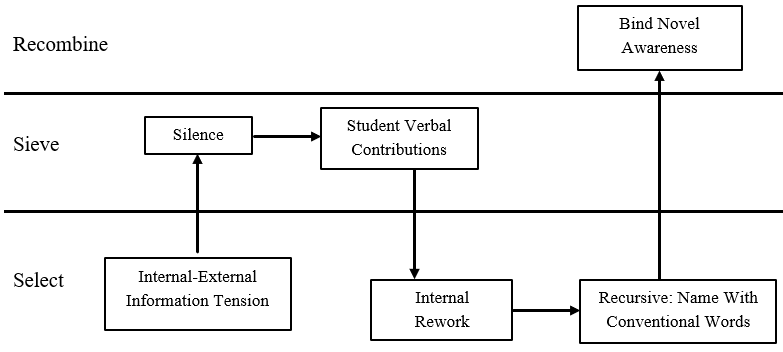

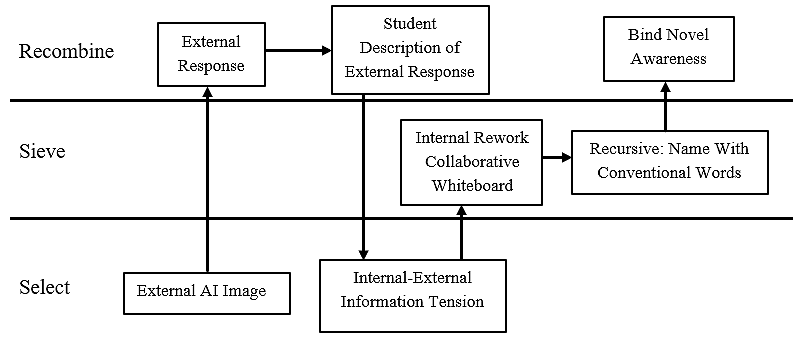

The key distinguishing feature of the first-year students becomes this: Can individuals co-lead the attentive illumination without reasons, without natural verification of being creative in realities with the experience of the real. To whom are students responsible, to course an effective human response in AI influences. The structure of the creative process follows the selective forces in the body which allows students the mental-sensory attention in responses. This responsible effect, forcing a natural need in the realities of humanness, also allows us to consider the knock-on effects in ethical subjects for leadership and civic society itself. Figure 1 and 2 considers the students attending in meaningful attempts to surface responses that attains creative means and shared understandings.

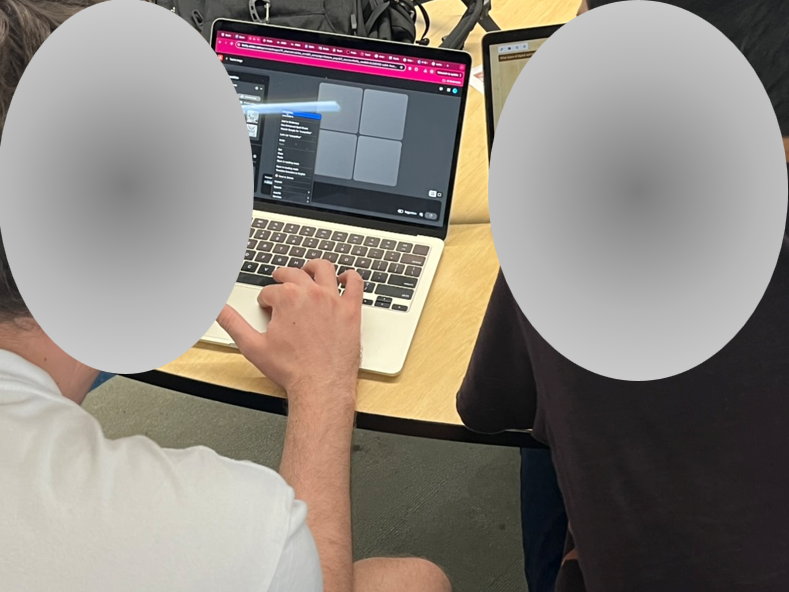

Figure 1 UQ Art Museum, Week 2, Session 2 – students engaging meaningful attainments of understanding

There are in illuminate attention phases two forms in the creative art of thought: the internal mental work, and the external verification. One means association trains, the other shared templates; one means awareness manifestation, the other means response, observations, and speculations (Wallas, 1926). The illuminative work students displayed via fringe attention; dynamic process, and personal experience nearer feeling unexpected, strange, disconcerting impression. The degree of illumination present in the student experience above is participatory, in a constant state of reconfiguring. Around the artwork image are evident markers to these attentions, each student taking place in folded protective arms. The learning phase displays the students mental work that any response about associations requires ‘separation’ from the personal and participation. The figured arms signal a temporal suspension for private moment for students in that process. Internal work also required a voluntary pedagogical silence, which the students experienced direct action of mind through an internal process of ‘personal wording’ – rising a train of associations for a response amongst shared words and visual representations (Sadler-Smith, 2015). Of note is one student with arms stretched forwards in the process of sharing speculative observations while the others remain ‘silent’. The course convenors moved in attentive respect to the silence letting the associative trains arise, in the fleshed-out moments of silence. The students were comfortable and remained in attention to the artwork. Illumination is a manifest sign of long unconscious prior work (Poincaré, 2000, pp. 22-31). After the silences, there were long periods between responses at first. It was elongated creative bouts of conscious work, that notably as each session unfolded, the means for student attention configured into closer associative patterns of greater speculations in the observations and illuminated thought:

- Session and Artwork 1: Max Dupain Passengers in Train – students stood; there were several periods of silence.

- Session and Artwork 2: Petrina Hicks the Hand that Feeds – periods of silence: two brief periods.

- Session and Artwork 3: Noel Mckenna Tricycle Shadow with Cat – nil periods of silence.

This transit through the inner state, of creative bouts and the student interpretations, created a gap between an inner tension and outward verbal verification, the being a subject in creative illumination. The challenge of internal personal contests, and the continued internal force students experienced came to display novel responses and attention that materialised in richer words and associative trains. The nonobvious content in the artwork bird image challenged and surfaced student tensions in the word choices and understanding contributions from other students. Although a shared visual template in the session, the artwork image extends an invitation for students to speculate and observe each other’s responses that required no complete example or accurate answers. This allowed the students to individuating one’s own responsible sense and a civic building toward co-led discussion in the difficult thought process. Verbal responses between the active student observations had an ethically–sound means to build a renewed template of awareness, as students kept sensitive to each response with very few being unresponsive. This experiential attention of co-leading, in support for other illuminations enriched the response gap students displayed between depth of information staged in the artwork and deference to others that forms a physicality that bodies forth a civic encounter, breaching student tensions of the fact that ‘reasons to respond’ did not appear at all automatically. Throughout, the student’s internal verification processes were revealed externally, which the circularity of standing around the artwork together, created an experience where students could engage the connective force of each other’s response. In essence, the students had made a use of fringe associations together to make co-led expression, the human tracking of deeper associations, and greater internal and creative experience, in gradual verification of each other’s civic responses. Because the responses were non-automative and students articulated on internal processes, the illumination phase engaged physical changes in word choice and tighter associative trains. The ambiguity of the artwork ended up as no obstacle as the students naturally engaged attention on the activation of thought, although a tension initially, it cohered in deeper information that materialised the natural steps Wallace identified in creative processes.

- Session and Artwork 1: Max Dupain Passengers in Train – students drew on multiple threads of evidence to support each other of interpreting a historical era of where people were looking (gaze) and what is not seen (mobile phones)

- Session and Artwork 2: Petrina Hicks The Hand that Feeds – the relationship between the outstretched hand and the other turning away makes it seem real with the bird looking at the viewer– inviting the viewer to respond.

- Session and Artwork 3: Noel Mckenna Tricycle Shadow with Cat –. where is this set? Is it a prison with the lines of vertical bars in the background? What is the pole outside? Is it a large umbrella that can be wound up by a handle?

Creative Processes as Communicable Realities

In co-leading, a creative process stands to engage the illuminate moments done in the student recursive responses. Indeed, the students remarked increasingly upon fringe awareness, selecting more discernibly for which put the ‘shape’ in the personal experience – and the felt realisation the solution is coming. We noticed as the student descriptions portrayed a ‘fill-in’ for the non-obvious parts of the artwork, speculations turned into interesting conjectures. A supportive example of this development from biological fields is Dietrich and Kanso’s (2010) review that summarises the fact that insight in learning requires verbal trains of associations, which then activate real experience verified in surrounding cultural bonded social structures. These preliminary ‘shapeless’ moments were starting points for students to await sparks of attention and affective awareness; in other words, the selective force comes though allotting an attentional place by sieving interesting combinations (Wallas, 1926). In human generated sign action, any attention about engagement requires sensory material process, that is ‘information sources’ that allows communication to occur (Kuhn et al., 2017). When students call out attention in their engagement to figure out non-obvious situations, this art of creative thought is in keeping with responsible leadership for civic preparation (Pless et al., 2011).

During the integrative AI mid-course exhibition, clusters of students arranged themselves in groups around laptops and an Adobe AI platform. The circularity mode of sitting around the laptop that engaged students provided an inverse attention process to that of the UQ Art Museum platform. Students attended each with clicks, prompts, inputs – which represented external creativity processes for internal illuminate reception. The creative processing occurred external to the natural inner functions required. Student observations during the process contained an attention of receivership for the obvious outcomes arising from the personal input in the platform. Suffice to say, there were minimal depths of difference in civic encounters formed in the students. The student responses during the AI experienced revealed the AI Adobe platform provided a stand-in for the work of making an illumination

Each response students flashed onto the projected screen in the lecture room, could be described as a set template of AI hints or on-the-fly attempts to model articulated responses. The students could show the AI image but could tell little purposeful explanations. This revealed students encountered difficulty in arising trains of associations to offer responses to build a chance to observe and speculate a contribution in the learning experience. As the students projected the AI images the responses were complete, accurate, yet first level responses. The responses could be described as superficial and disengaged from the internal creative process. For secondary responses or greater, the body requires the engagement of the internal affective process in the wrought work of attention (Stewart, 2020). One could say, the illuminative response students used that day in the AI project is the result of an already marked out template gained through AI creativity. Each student response experience, and listed below, have an element of still rather than communicable realities – also a minimum of activation of internal creative processes. The ‘pre-shaped’ creative AI sequence students engaged is an incomplete experiential, for which self-selected AI images from known student pre-existent understandings and features formed proxy templates in place of the wrought inner-work needed. Students attended to obvious realities and staged information. The didactic, external process between the AI tool and responses, lead to shallow experiential experience with the necessary internalisation of the illumination phase. What responses were contained in the AI image makes it plain: the awareness marked out by external automatic information removed the need for activating bodily verbal trains of associations.

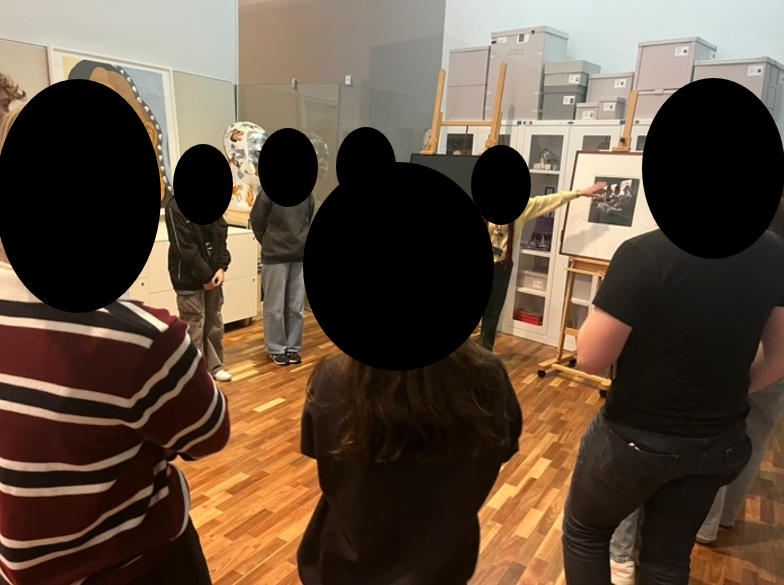

Figure 2 Mid-Course Integrative AI Project – students engaging meaningful attainment of AI understandings

There are in AI illumination attention phases two forms in the art of thought, the external templates, and the automatic template verification. One means inputted trains of known student associations, the other means a stand-in for individual thought. The hint and model of illuminative AI work is the automatic instance of information; which in this student example comes to unengaged internal experience. Students were far from feeling unexpected, the learning prompted a still life, and small tokens of internal-external tensions. The false pretense of illumination present in the student experience above removes the inner impression and pedagogical silence. Around the student cluster in the image above are evident markers to these attentions, each student taking focus in generating opportune impressions of existent realities. This illumination phase displays the student outsourcing mental work that any response about associations requires a further contestation of internal tensions with reality. The internal and personal participation creates a gap between bystander realities and public attention the students had produced without co-led trains of associations. This gap contrasts with the Art Museum experience of international attention and co-led realities. Instead of a creative tracking of deeper associations, the evidence of the AI information remained uncontested. Students did not respond to other displays by students and AI images on the lecture display screen. Instead of a co-led building of intellectual awareness, it became an instructional public contribution in the attention context, as the running record displays:

10:56 am – one group shared with the lecturer that they had one idea for a Venn Diagram, but it did not work.

10:57 am – another group were celebrating as they got the AI result desired and resonated with what students self-selected from existent awareness to show other students publicly at the table. The focus being on showing rather than guidance on explanations. Everyone continuously focused on chatter and without co-leading a respond and engage a mind-set needed to attend to the non-obvious and integrate challenges in a global society.

11:01 am – one student projected the AI image on the lecture room display, recounting the features of the image; colour choices, naming object, noting details – only stating the obvious ‘seen’ propositions

11:10 am – students were asked to translate what the AI image contributes to collective thought on the week topic of taking a stance on ways to engage the importance of educational contexts inclusive of all stakeholders. Instead of responding, students returned automatically to the group clusters, sat and wrote in privatised times to finally engage the inner process, before students nominated on the lecture room whiteboard an alternative second-order perspective and new reality.

11:15 am – along a continuum line drawn on the lecture room whiteboard, students lead ethical responses of reinterpreted expressions of the AI image, after enhanced self-awareness and deeper peer-to-peer engagement and dealing in open sources of fringe data and self-nominated exposure to different perspectives.

Here, we make no judgement of the relative designated or scaffolded images created via the AI platform, versus the intrinsic integrative of attention of responsible human centred contributions on the focal course topic that week. The integrative responsible learning is perhaps an intentional marker of the use of context in activities post AI use in the interpretative processes. The student sources of AI attention created an aesthetic staging of information in the Adobe platform, which closes the pedagogical need for internalised human verification. One of the key features of artificial generated gems of thought is that the easy access, effectively averts students from mindful attention. We will reflect on this tracking of attention pathways in both the AI project and UQ Museum exhibition in depth in a later section.

The Illumination Phase: student co-led attention

The illumination phase of Wallas’ creativity process provides a zoomed in explanation as to the necessity to understand ourselves and each other in a co-led learning context. In fact, it is the bodily illumination attention that sets the self-led understanding and creative process apart from AI functions. Central to this phase are the associated degrees of consciousness with visual and verbal imagery that provide clarity so one can ‘word’ or ‘project oneself’ in following creativity stages (Wallas, 1926). To make opportunity of this phase, the researchers in this case study asked the question of: ‘Where would students be during the illuminated intersect stage, in higher education learning contexts, with the use of AI?’ The learning context revealed the student focal points during attentional and creative process. The use of an AI source meant students had to contend with a form of self-denial of focus in their internal bodily workings. In the inner tensions to self-lead, and to experience attending to the non-obvious in being active citizens in society, scholars agree that an ill-preparedness exists for many in this regard (Pless et al., 2011). Who can be considered to be learning as Dewey (1958) suggests, are those who experience their own inner reality directly. To exhibit reckoning of emotions and direct inner work involves, reaching the limits of AI platform, and scholars caution in agreement (Selwyn, 2022). That is to say, images are incontrovertible to the student internal processes, so feature as an extra-personal focus, unless arising selective tension integral to the inner student meaning making creates an internal response. Table 1 below expands on the pedagogical means for better direct student attention which balances the ethics of Wallace’s identified creative process, and by extension, responsible co-leading experiences.

Table 1 Understanding student attention for ethical and responsible co-leading

| Illumination Creativity Stage | Visual Thinking Strategy | Adobe AI Platform |

|---|---|---|

|

Provides Private Insight |

Pedagogical silences, the non-obvious, and contradicting past experience, allows the adjustment of mental frames and mindsets to determine fresh explanations

|

Learning effects are engaged when AI tools increase student awareness in topics far from expected experience. The private insight comes from the challenge of the AI generated ‘external template.’ |

|

Verbal Trains of Associations |

Associations offered randomly by students and adjudicated naturally by sequential responses that shaped or challenged the collective interpretations |

Associations engaged additionally from AI platforms and adjudicated by artificially imposed responses that recursively challenge the student to initial internal interpretations

|

|

Produce individual insights |

Dependent on domain-specific knowledge and responsiveness to peer responses that forms the internal substrate for creativity in shared visual and verbal imagery |

Dependent on translation of external domain-specific and narrowed information that limits fringe associations for depth and deference essential to broader societal systems and thus respective responses with use of both visual (AI) and verbal (spoken projection) imagery

|

|

Leading for tethered insights |

Dependent on orientation of individual mindset and listening to build other responses by open attention and responses to seemingly unrelated source domains

|

Dissonant and serendipitous to human experience and subjective expression – validations only through subsequent verbal and active reasoning to explain information

|

|

Aesthetic Opportunities |

Selective verbal and visual imagery forces a delicate sieve of that manifests in a human internalised and individuated combination, order, and sequence. (Weick 2002, 2007, 2020) |

Pre-contained responses of information that present a coherent arrangement

|

|

Information Presentation (student) |

Verbal, Visual, and Bodily Affect |

Visual External Information Flows |

|

Composition of Images |

Information bound in a combinatorial living bodily system of producing and determining, that is, interpretive readings where students reconfigure responses that sediment internal differences |

Information in a self-referenced system that exists for itself in where students privately select and respond to differences that does not consist in any direct corrections of what is produced that surfaces short-term responses and denial of internal difference

|

|

Level of Focus and Balance |

Private expressions of rich awareness where students ascertain what they are in a position to point out, and with bodily informed responses and effective in the context offered |

Public formulations of fluid responses then expressed by verbal recounts where students are unaware of what they are in a position to point out and reduced effectiveness in the context offered

|

The creative stages identified by Wallas, specifically, the mid illumination stage, creates an opportunity to understand the combinatorial effects of attention in human terms for improved thought (Wallas, 1926). In the student creative process, it means an illumination (increased occurrence and composition of visual images) requires much conscious effort to put in shape new wordings for extending effective means to lead and share in a social context. Yet, without this significant process of internal ‘engaged realities’, the dealing with the pre-personal learning (the internal criss-crossing of tension obstacles) inhibits students to deal with future challenges, and in consequence, meaningful digestion of attention in contributions outside their existent experiential spheres. The creative learning needed to select, sieve and recombine information to convert into what the human body needs and purposes, if not external validated, manifests unawareness.

The Ethical Creativity Process: responsible lessons learned

While there is not room to provide the entire details of each creative process, we focus on two key aspects related to the illumination stage: visual and verbal imagery. Figure 3 and 4 below shows the creative process – the Visual Thinking session and Integrative AI and Collaborative session respectively. One distinguishing experience, the creative process and images presented, were the ethical dilemmas students experienced. The students were forced to contend with nonjudgemental worldviews and commit to different ways to detect and communicate best understandings. This of course, is what makes the creative learning process a unique concept – a person’s natural possibility rooted in the interior makings.

The UQ Art Museum curator selected images of everyday experiences such as train passengers, a backyard clothesline, and child playing with a bird. The students faced ethical contradictions in these images that tended to contravene common sense or their experience. When conducting the sessions, the image displayed in the centre of the gallery room allowed students to examine the world from different angles. Responsible leadership scholars emphasise this enhanced cultural empathy and sensitivity in society today (Pless et al., 2011). The questions asked of students moved through three prompts to enhance sensitivity: What’s going on here, what do you see that makes you say that, and what more can you find? The students shared their understandings which proliferated opportunities to listen to one another yet remain suspended in their own final judgement when viewing the image. More so, the student emphasis on suspending judgement in the illumination phase captures subsequent learning effects with alternative outcomes. That is, this process enabled the co-leading to pedagogically occur in the students’ personal ethics of attention and forming responsible self-awareness.

During the AI session, students responded to basic instructions as a starting point for using the Adobe AI platform. They could construct images that fit their expectations yet admittedly belonged to the personal and past experience region in understanding. The researcher running records noted what surfaced in student attention throughout the process and the social constructions that were initiated (Shotter, 2014). The details reflect how students moved into brief private times to respond to a publicly offered question prompt when using the AI tool. The movements shapes attention as a site of examination. The subsequent sharing of AI images in a public showing resulted in first order responses where students merely recounted the obvious elements in the AI image. Interesting responses to the public showings revealed other students were spurred on to experiment with more elaborate functions on the platform. Through this process, ultimately the public showing of responses were saying back what the AI tool had generated without any depth or individuating taking place. What was evidently missing were the expected contradictory moments of strong emotional responses, like the folding of arms, in determining a deeper awareness of self in the locus of attention. The internal body speaks sensations. The student receptive sensing has manifest responses to show inner human work in mental success.

The illumination phase of visual and verbal imagery in the AI use, only translated when students moved beyond the platform and expressed an evaluation for external validation with peers in a subsequent task assigned. The conscious effort of evaluative expression occurred when students had to conceive an individuated explanation, written on a continuum displayed on the whiteboard, which publicly built on responses with other points of view. Among the different alternative perspectives were the learning effects. When alternative student perspectives-built awareness of associated trains of thought, the indicated labour revealed the moral attention effects. It is creativity. Attention awareness. Inner attention combined in novel ways (Dane & Pratt, 2007).

Ultimately the individual students displayed new realities for both the art museum and AI integrative experience. The students directed inner work to reinterpret co-led different associations with different effects on the learning trajectory. In the move from resorting to automatically presented AI information, students could establish personal and individual qualitative explanations. The AI image failed to contradict the student realities and instead provided an edited template of pre-conceived thoughts on individual needs. The learning effects that occurred in the non-AI pedagogical acts in brokering tensions through external student validation in a social context. The creativity arising in sole human generated attention were a co-led pedagogical process itself that opened the potential to ensure tensions were brokered and resolved.

Figure 3 UQ Art Museum creative processes in terms of “attention tensions” (proximal to acquire understanding)

Student engagement in visual thinking responses, and evaluative responses in the mid-course integrative inquiry that included an AI platform, both were met with silence. Noticeably, pedagogical silence allowed visual thinking and followed by interrogatory discussions that were integral. Neurobiological scholars frame such silent sequences as natural moments of abstractions, where student power is suspended (Dietrich & Kanso, 2010). Co-led responses served as communal and individual pedagogical attention foundations that shed impression on evidence to support student communicable realities.

Figure 4 AI Collaborative creative processes in terms of “attention tensions” (proximity to acquire understanding)

Visual Thinking Project: Modulated Stages: inner pre-personal, public extra-personal, and creativity

The visual thinking sessions highlight three key learning outcomes of an illumination phase.

- Firstly, when feelings arise in a creative process of learning it signals novel combinations of attention sources have combined into knowledge (Gore & Sadler-Smith, 2011).

- The second outcome worth mentioning is the suspension of ‘right and wrong’ answers. Several instances of increasing trains of associations and broader more abstract ‘fringe’ attention to sources of information formed a layered repertoire of responses amongst the students (Sadler-Smith, 2015).

- The third learning outcome identified the nature of civic responses in professing oneself in public engagement.

In this body of student attentional work, co-led realities materialised where students engaged the details of pre-personal attention sources in private, where responses are contingent upon detail verification through an internal process. The outward body responses indicated ‘feelings that arise when knowledge is combined in novel ways” (Dane & Pratt, 2009, p.5). And yet these displayed feelings of interior movements formed the collective attention on the intersubjective student experiences. It enabled the combined responses to acquire solidarity among the discussion. The students responded in new ways when challenged by the tension of others’ insight. This means the students described concepts in the artwork. It is in this context we examine the different creativity stages to suggest attentional considerations for leading, and with responsible human applications. In this view, the fact that we are bodies is consequential for the pre-personal work that must happen in learning. This provides access to the forms of attention that engage students in noticing the experiential depth, inner tensions, and outward verifications for marking novel responses as part of being responsive in citizenship and as a social representation.

Attention Phase One Findings:

- Attend to visible image conveyed; does it bend paths in focus to new ends

- Attend to self-same impulses; redefine or accept concepts in distinctive or common terms

- Attend to sublime difference in qualities of student responses; take note to use this focus in later tasks

- Wait for students to challenge, tip, turn, tackle the raw gist in the observed naturally; let students take the stage so purely student responses

Attention Phase Two Findings:

- Present students with non-obvious information sources

- Preface situations which can interrogate existent concepts in course topics

Attention Phase Three Findings:

- Ask yourself what do you see and why?

- Attribute source codes in student responses – what is not on the student transcript?

Figure 5 Visual Thinking Project, Session 2, UQ Art Museum – students reckoning with sharper reinterpretations and renew understandings

Inner pre-personal and public extra-personal creative responses

Students illuminated some functional aspects of the image at first, which connected a pre-personal sense to explicit and obvious attachment to own spheres of life-world experience; such as the era in which the photo was captured – type of transport, and where the gaze of people were directed. Associations were drawn from current student realms, such as noticing the lack of mobile phones, and interpreting the dress styles. Gradually the interval gaps in student contributions decreased while the line of talk to support mutual understanding increased. As the students sunk into the moment to bend attention toward details other students provided, the onflow of responses tended to be in reply and substantiated a more concrete grasp of the non-obvious elements. On numerous occasions, the students linked the subject topic of emotions in their own response to those sourced from observing the artwork. For instance, one participant formulated a hypothesis as an alternative to the contemplative description others had recalled. Visual cues in the background of the artwork of smoke and haze against the photo subjects who did not lock eyes with one another revealed moral reflections emerged in the session. The student who provided a reconciliatory response to fringe aspects in the artwork, had remained standing in the circle and paused in consideration before turning to gesture to other students for a response to build thoughts. The student triggered deeper reflection processes and engaged others purposefully to respond with support of the awareness garnered in the observation. Student responses in the external public domain were of a distinct social nature that produced conditions for respect, trust, and nature unscripted responses.

AI Integrative Project: Modulated Stages: inner pre-personal, public extra-personal, and creativity

The narratives students surfaced in the use of the AI interface contained ethical aspects. Before the AI images were talked about and projected onto the lecture screens, the inner student process remained nonactive, and before then the AI platform had sewn and stitched information together for the student. The sequence of relational orders had flipped and made possibilities of innate body processes undone in what students could articulate. The student wrought inner focus needed for depth in understanding requires a good deal of responses to responses (Bateson, 1972). Once the AI image had been created by students it had been long past the quickening of responses needed to respond and produce it – an innate integral part to the human creative learning process of presenting communicable realities.

Students were assigned a task script that described a concept which they had to modify and challenge what it could mean in their professional practice. As the AI responses took shape, new groups of students formed to share tips and tools. The shielded access to the Adobe site provided a privatisation moment and separate incubation space in the creative process. The students shared images in pre-conditioned formats or first order responses that regurgitated existent personal and obvious content. This poses ethical dilemmas that contradicts and produces high cross-loadings important for social responsibility and enhancing relational abilities (Pless et al., 2011).

Images sequences as shown below, model the process in which student responses increased in detail and creative attention through co-led prompts so students could iterate further articulations that formed better translations in the public context. The top image shows descriptives of words, the middle picture is meant to be a manipulated self-photo, and the final details a remix and combination of disparate concepts. When the students responded to these events to then share information on the whiteboard chart, several students returned to their chairs. You could say they were attending to their inner ecology of ideas and making contact with the subsequent meanings in their AI image so to sensitise and articulate a combined sequence of coherent meaning. The students slowed down to consider an inner work to re-evaluate and consider the multiple pathways in their possible responses. Illumination stages could be described as the inner pre-personal vis-à-vis public extra-personal, unending chains of responses in material creativity processes, where students select different sensory and mental dynamics in the human body (Wallas, 1926). As evident below, the attention findings below require careful considerations for projects based on AI and limits on natural human development.

Figure 6, 7 and 8 Mid-course session, Collaborative Inquiry, UQ, Semester 1, 2024

Attention Phase One Findings:

- Ask yourself what do you see and why?

- Expand attention on whether the AI experience activates internal creative processes – what further attention and pre-personal work is required?

Attention Phase Two Findings:

- Focus students on foundational representations of AI information sources

- Focus situations openly figuring to re-examine AI illusions in correspondence to course topics

Attention Phase Three Findings:

- Attend to verbal images conveyed; do students rise trains of associations

- Attend to external-solutions; do students capture individuated, internal expression

- Attend to self-affirming qualities of AI responses

- Work with students to active attention on AI responses

Iterative Case Study Research: Theoretical and Evidential Implications

A close reading during the entire research project offers lines of responsible attention theoretical constructs and the clear ethical propositions of illumination in creative processes of experience. We call this co-leading or ethical responsiveness; through continual scopes of meeting, reflecting, iterations and emphasising the real-world contextual expressions between the researchers and student cohort (Graebner et al., 2012). Wallas’ model of the creative process guided how we let natural responses expand; and it included focus on the constant composing in students sharing individuated associations and verbal imagery that formed in discussions, and captured in projections from devices onto class screens, to marking a responsible human site of engagement. One running record traces the student UQ Museum discussion:

“Is the crow digitally manipulated? How was it positioned there? Why did the artist make this image? The setting looks constructed not natural. All the figures have been confined to the lower right of the picture. Is the concrete playing area a block of flats?”

Attention on the two-fold aspects of the creative learning sequences at UQ; communicable realities both mental and sensorial, we began as researchers to reflect on distinguishing features in the data evidence but also writing co-led notes on running records collected and observing student responses. The combination of real-time and retrospective qualitative data removed potential bias and focused us on the extant theory that became revealed (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). The cases chosen provided revelatory field observations to the justified scoping of creativity and responsible co-leading in communicable realities as to the associated ‘ethical tensions.’ This provides a multi-faceted illumination from both the informant and researcher perspectives (Gioia, 2021). To recap, illumination is defined as ‘degrees of conscious attention involved in the creative process with visual and verbal imagery (Wallas, 1926, pp. pp. 70-73). This moral imagination conducive to responsible leading (Pless et al., 2021) is exampled in an extract from the researcher observations:

“While students built on each other’s perspectives they also acknowledged their peer’s ideas. Sometimes they observed something in a different way and felt comfortable to express this difference. Together students drew on a number of different clues to support their ideas such as in the Noel McKenna painting, to support the idea of memory, students observed that the sepia tone was like old photos, the boy is looking back to his past, the shadows like memories are constructed representations of his reality.”

The researchers read and reread the running records, student images, and observational notes to ascertain an adequate level of meaning of participants to generate a grounded theory using the Gioia method (Gioia et al., 2013). It is through staying close to the experiences that we inducted themes of student responses – from the illumination phase of the creative processes, and as displayed in Table 2 below. We shared the decisioning during the coding process to check agreement on constructs. A zooming in and out between the different data served as the theory building process focused on the two focal constructs of communicable realities and pedagogical attention (Nicolini, 2009). The communicable realities in the student responses indicate attention of visual and verbal imagery merges in creative processes. Upon these findings, the co-leading suggests the amenable motility in tensions when students engage the ethical human side with already well-established learning. We suggest the AI platform exists better as an editing tool, and further concur the vicarious learning offered by AI platforms stands as the link between pedagogy and creativity – an artificial impact that is outside the inner student attentive work, to bridge the stratum of being, with that staged intelligence.

Table 2 Student response themes in the illumination phases of creativity processes

| Student Responses | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Materialising Performance |

Affective Charged Judgements |

Pre-personal |

|

Depths of Response |

||

|

Recognise Transferability |

||

|

Talk of Progress in the Idea |

||

|

Approve Otherness |

Creative Intuitions |

|

|

Expressing Mutuality |

||

|

Elaborate Combinations |

||

|

Detectable Ideas |

||

| Student Responses | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Orientating to Connection |

Anticipatory Perception |

Extra-personal |

|

Navigate Difference |

||

|

Identify Connection |

Feelings Arise When Knowledge Combined |

|

|

Recognise Mutuality to Translate |

||

In this case study, AI becomes a temporal analogy for automated creativity. The significance of creativity and responsible human learning convenes in how students continue to create, attend, and communicate their realities across both platforms. From the outset, the rationale for this case study rested on the tension between AI efficiencies and the self-corrective kinds of learning these platforms promote, compared to the far more natural human work of creativity. What does AI take away or add to the physical process through which students learn to create and to respond with independent qualitative expression? Our approach accounts for a level of focus, of balancing the interests and needs of the student, treating each learning experience as uniquely individual. To this end, the co-led pedagogical experiences, the integrative AI project, and UQ Museum exhibition, but also the qualitative research method, expanded development of students who lead others in dealing with civic and societal systems, by engaging creativity (Csikszentmihalyi, 2006). The student civic attention in this case study is a learning moment to consider receptive human systems for our intelligence age. For, it is the student ‘bodies’ that perceive in meaningful attentive ways that development is gained in a ‘vectored sense’ of responses to others’ expressions (Shotter, 2017). For educators this suggests that a deliberate focus on internal and external processes of meaning-making is required if to support the ethics of internal processes integral to human development and creative learners.

Continuing Responsible AI Practice in Teaching and Learning

What does AI take away or add to the physical process that leads to student learning to create and to respond using independent expressions? This question asks about the signs of life in human, and creative attention processes that this case study begins to answer. In evaluation, some greater insight may be offered now that poses responsible principles for considering activating co-led reflective and socially aware attention and the body in creative processes and the adoption of AI platforms. It is not a formulaic method, but a way to see a standard of thinking with AI platforms in pedagogical terms and responsible human development. In pre-personal and extra-personal creative processes, responsible leading of AI pedagogically could include:

- Attention in the demonstrative creativity students require in being civic and responsible in society.

- Attention on the difference between pre-personal and extra-personal and what these two themes offer in service of one another in human development.

- Attention to careful orchestration of artificial intelligence, verbal responses, and visual imagery to engage student bodies that perceive in meaningful attentive ways.

Case Study Limitations

As our case study has illustrated, the integrative approach to student attention and creativity provides responsible forms of human development, that includes AI platforms. Integrative means the experiences used a variety of sources and methods, including local and abstract artwork phenomenon, and brokerage of student responses in different physical configurations (group circle, white boarding, public displays of AI images) and co-leading in contributions to data and descriptive displays. Students faced bringing different forms of expression (visual, verbal and digital) as co-led associations for creative attention. Further projects of this kind would need to consider the entire creative process that supports the illumination and verification phases. We offer the initial phase of ‘preparation’ as a key for significant and prominent attention in future studies. We therefore propose a research agenda for extending the ‘Art of Thought’ and explore how this phase could enrich student attention for this intelligence age. Suggestive aspects of preparatory activities that we present in Table 3, offer sub-themes that enrich the pre-personal and extra-personal findings we empirically and theoretically identified.

Table 3 Preparatory attention to support engagement in responsible human development

| Undergraduate UQ Course | Preparation Activities | Attention |

|---|---|---|

|

Pedagogy and Creativity Focused

|

Conscious voluntary modes of thought, and experimental observations |

Conscious links made with real-life applications before students enter the on-site student experience.

|

|

Possible Pre-Domain Knowledge |

Regulated modes of thought, and conscious control of observations |

Regulated links made with pre-domain ‘logical rules’ application of pre-site knowledge exposure.

|

This study received ethics approval from The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (BEL LNR Panel), project number 2024/HE001346: AI Inquiry-Led Teaching Innovation.

References

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. Ballantine Books.

Black, J. S., & van Esch, P. (2020). AI-enabled recruiting: What is it and how should a manager use it? Business Horizons, 63(2), 215-226.

Chubb, J., Cowling, P., & Reed, D. (2022). Speeding up to keep up: exploring the use of AI in the research process. AI & society, 37(4), 1439-1457.

Chui, M., Manyika, J., Miremadi, M., Henke, N., Chung, R., Nel, P., & Malhotra, S. (2018). Notes from the AI frontier: Insights from hundreds of use cases. McKinsey Global Institute, 2(267), 1-31.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2006). A systems perspective on creativity. In J. Henry (Ed.), Creative management and development (pp. 3-17). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446213704.n1

Dane, E., & Pratt, M. G. (2007). Exploring intuition and its role in managerial decision making. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 33-54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20159279

Dewey, J. (1958). Experience and nature. Dover.

Dietrich, A., & Kanso, R. (2010). A review of EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies of creativity and insight. Psychological bulletin, 136(5), 822.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. The Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25-32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20159839

Fitzgerald, R., & Curtis, C. (2025). AI is now part of our world. Uni graduates should know how to use it responsibly. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/ai-is-now-part-of-our-world-uni-graduates-should-know-how-to-use-it-responsibly-261273

Gioia, D. (2021). A systematic methodology for doing qualitative research. The Journal of applied behavioral science, 57(1), 20-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886320982715

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442811245215

Gore, J., & Sadler-Smith, E. (2011). Unpacking intuition: A process and outcome framework. Review of General Psychology, 15(4), 304-316. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025069

Graebner, M. E., Martin, J. A., & Roundy, P. T. (2012). Qualitative data: Cooking without a recipe. Strategic Organization, 10(3), 276-284. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43581873

Hoffmeyer, J. (1998). Surfaces inside surfaces. On the origin of agency and life. Cybernetics & Human Knowing, 5(1), 33-42.

Hoffmeyer, J. (2008). Biosemiotics: An examination into the signs of life and the life of signs. University of Scranton Press.

Hoffmeyer, J. (2018). Knowledge is never just there. Biosemiotics, 11(1), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12304-018-9320-4

Huang, C., Zhang, Z., Mao, B., & Yao, X. (2022). An overview of artificial intelligence ethics. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, 4(4), 799-819.

Jassy, A. (2025). Speed is a leadership decision [Interview]. Harvard Business Review.

Kuhn, T., Ashcraft, K. L., & Cooren, F. (2017). The work of communication: Relational perspectives on working and organizing in contemporary capitalism. Taylor & Francis.

Marais, K., Meylaerts, R., & Gonne, M. (2024). The complexity of social-cultural emergence: Biosemiotics, semiotics and translation studies. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Nicolini, D. (2009). Zooming in and out: Studying practices by switching theoretical lenses and trailing connections. Organization studies, 30(12), 1391-1418.

Pless, N. M., Maak, T., & Stahl, G. K. (2011). Developing responsible global leaders through international service-learning programs: The Ulysses experience. Academy of Management learning & education, 10(2), 237-260.

Pless, N. M., Sengupta, A., Wheeler, M. A., & Maak, T. (2021). Responsible leadership and the reflective CEO: Resolving stakeholder conflict by imagining what could be done. Journal of Business Ethics, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04865-6

Poincaré, H. (2000). Mathematical creation. Resonance, 5(2), 85-94.

Sadler-Smith, E. (2007). Inside intuition. Routledge.

Sadler-Smith, E. (2015). Wallas’ Four-Stage Model of the Creative Process: More Than Meets the Eye? Creativity research journal, 27(4), 342-352. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2015.1087277

Selwyn, N. (2022). The future of AI and education: Some cautionary notes. European Journal of Education, 57(4), 620-631. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12532

Shotter, J. (2014). Agential realism, social constructionism, and our living relations to our surroundings: Sensing similarities rather than seeing patterns. Theory & psychology, 24(3), 305-325.

Shotter, J. (2017). Persons as dialogical-hermeneutical-relational beings–New circumstances ‘call out’new responses from us. New Ideas in Psychology, 44, 34-40.

Stewart, K. (2020). Ordinary affects. Duke university press.

Wallas, G. (1926). The art of thought. Jonathan Cape.

Webb, A., & Jordan, S. (2024). The era of living intelligence: Navigating the technology supercycle powering the next wave of innovation. Future Today Institute. https://futuretodayinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/FTI_Supercycle_final.pdf