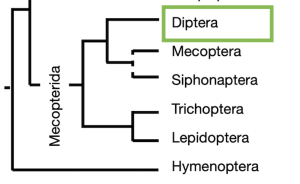

36 Orders of Insects: Diptera

Order Diptera: Flies

Diptera

- common name: flies. Sometimes called “true flies” because other non-dipteran insects are often called flies, e.g. fireflies are Coleoptera, butterflies are Lepidoptera

- from Greek: di = two, ptera = wings

- worldwide distribution; one of the largest insect orders, about 153,000 species worldwide

- found in all types of habitats

- structurally, most highly specialised Order of Insecta

- extremely important vectors of human and animal diseases:

- human diseases: malaria, yellow fever, dengue, cholera, Ross River Fever

- animal diseases: dog-heartworm; blue tongue, anthrax

- reasons for their success:

- complete separation of larval and adult niche

- female lays eggs directly into larval food supply

- larvae extremely well adapted to exploiting organically rich “muck”

- adults with highly sophisticated flight are excellent dispersers, colonisers which often use nectar of flowers as fuel for flight

- only ingest liquid food in various forms

Characteristics of Diptera

Adults

- Small to medium sized

- haustellate mouthparts, collect food in liquid form; variable in form: biting, sponging, sucking

- large compound eyes; ocelli present or absent; antennae filiform, stylate or aristate

- only one pair of membranous flying wings; hindwings reduced and modified into small, club-like structures called halteres (balancing organs)

- mesothorax enlarged to accommodate flight muscles

Immatures

- immature stages (larvae, maggots) variable in habits and morphology

- without jointed legs, with sclerotised head capsule and chewing mouthparts or reduced to remnant mouth hooks

- most feed on moist, decomposing items, but some predaceous or parasitic

two suborders

Nematocera – mostly small, delicate flies. For example mosquitoes, crane flies; antennae filiform

Brachycera – mostly stouter and larger flies. For example march flies, hover flies, blow flies; antennae are aristate or stylate

Notes:

The ancestral and still most common larval habitat is decaying vegetable matter (eg. leaf mould, compost, rotting or fresh fruit). Such substrates are moist and often considered “semi-aquatic”. Related environments are also frequently exploited, e.g. many larvae live in, and feed on, dung or carrion. Some have transitioned from feeding on putrid plant material or dead animals to feeding on putrid wounds of living animals (myiasis). Some have even become parasites of vertebrates. Aquatic life cycles have secondarily evolved independently many times especially in the Nematocera.

Some Diptera have become parasitoids, for example the Tachinidae, which can be useful biological control agents. One strategy is for adult female tachinid flies to stalk a caterpillar or bug and lunge forward, extending their ovipositor to place an egg on the host. The egg hatches and the 1st instar larva burrows into the host where it continues to develop.

Adult lifestyles (some common ones)

- Feed on nectar

- Extremely common behaviour among the Diptera

- Proboscis sometimes elongated to reach nectary in flowers with long corollas; many common flower visitors are bee or wasp mimics

- Feed on surfaces of decaying matter

- Very common in many Diptera e.g. housefly: Musca domestica

- Saliva secreted, surface dissolved (or in aqueous suspension) and sucked up; ingestion of microbes probably important part of diet.

- Free living (non-parasitic) blood feeders

- Common in Nematocera e.g. mosquitoes, black flies, biting midges; in Brachycera e.g.horse flies

- Almost always only the female sucks blood, male usually a nectar feeder. When host finding, flies are attracted to moving objects, heat and carbon dioxide and probably other odours are also attractive.

- Some of these families feed on insect blood as well as vertebrate blood (eg. biting midges); other Diptera feed on other body fluids eg. eye exudates: some eye gnats.

- Ectoparasites on vertebrates

- Usually ectoparasitic Diptera are blood feeders

- Some females find hosts then shed wings and become ectoparasites on birds; larvae are scavengers in nests. Body flattened, louse-like in appearance in some groups – adaptation for parasitic life on host. Hosts include wallabies, sheep, birds, bats, horses, cattle.

- Aerial predators

- Common in Brachycera, some common examples: robber flies, dance flies

- Robber flies are best known; they are often bee and wasp mimics. They will perch on an exposed object and wait for prey (often bees, wasps, dragon flies) to fly by. They are swift flies and will capture prey in flight. Stout legs hold prey and their thick “beard” protects eyes and antennae from struggling prey. The sharp proboscis penetrates prey and then toxin is injected.

More information

This CSIRO website has a fantastic interactive atlas of fly anatomy to help users learn anatomical terms used in fly identification. The Atlas was uses high resolution digital images and enables magnification to view finer details. Check out this great resource!

An Anatomical Atlas of Flies by David Yeates and Anne Hastings.

Topic Review

Do you know…?

- What is the etymology of the word ‘Diptera’? Is this appropriate for the order? Explain.

- What are halteres? What is their function?

- How are the adults of the two suborders distinguished?

- What are the three main types of modifications of mouthparts of adult Diptera?

- Why is the mesothorax of flies much bigger than either the prothorax or metathorax?

- Why are flies economically important?

- In what ways are flies beneficial?