8 NPV – Relevant Cash Flows

8.1 Introduction

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- explain why only incremental after-tax free cash flows are relevant in evaluating a project

- identify the relevant (incremental) cash flows for a capital budgeting project

- explain why tax computations are relevant to capital budgeting and how depreciation affects after-tax free cash flows (FCF)

- calculate the after-tax FCF for a project

- identify and calculate any initial and final year after-tax cash flows from capital transactions and changes in working capital

- compute NPV and IRR using Excel.

In Chapter 7, we discussed three commonly used project evaluation tools: Net Present Value (NPV), Payback Period, and Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Those three methods have one thing in common: all methods use cash flows arising from the project in their analysis. But, which cash flows should we use? Are they the same cash flows as presented in the annual “cash flow statements”? Are all projected cash flows relevant for capital budgeting?

In this chapter, we focus on the “cash flows” part of capital budgeting. In particular, we discuss which projected cash flows are relevant and how these cash flows differ from the accounting cash flow statement.

8.1.1 The Importance of Incremental After-tax Free Cash Flows (FCF) in Capital Budgeting

In capital budgeting, we are interested in something called the incremental after-tax free cash flows. What are the “incremental after-tax free cash flows” for a project? The term will be explored as follows:

- Incremental cash flows: The incremental cash flows refer to any net additional future cash flows generated by a company as a direct consequence of adopting a project. Incremental cash flows are often also referred to as relevant cash flows. This concept also means that cash flows that would exist regardless of whether or not the project is adopted are not relevant in project evaluation.

- Free cash flows: The free cash flows refers to the cash flow available to the debtholders and shareholders after all operating expenses have been paid and necessary investments in working capital and fixed assets have been made.

- After-tax: As a consequence of the free cash flows concept, we also need to take into account the cash outflow from tax payments to the government that will be applied to the profit or gain generated from the project. We will discuss later in this chapter that a project may generate a profit or gain from selling the fixed assets at the end of the project, which is a taxable transaction.

Incremental after-tax free cash flows are important because they represent the cash flows that can be paid out to creditors and shareholders. By discounting these cash flows at the cost of capital, we are essentially measuring how much the acceptance of a project would add to (or subtract from) the value of the company in today’s dollars. While the value of a company must equal the total value of both debt and equity (remember assets = liabilities plus equity), the value of debt is capped at the present value of the promised cash flows. Any increase in the value of a company will, therefore, go to shareholders. This means that the present value of the incremental after-tax free cash flows from a project is a way of measuring how much the project increases (or decreases) shareholder wealth.

Investors care more about cash flows than accounting income. If you invest in a company, you care more about how much dividend you will receive each year, because that determines the cash flows you receive. Having that cash flow, you can choose to consume or invest. On the other hand, you care less about the accounting profit or loss (unless this impacts the cash flow to you). This is because you cannot consume or invest that profit if you don’t receive the dividend. Also, accounting income can be distorted by non-cash items in revenues and/or expenses, such as credit sales, accrued expenses and depreciation expenses.

In this chapter, we are going to learn how to identify relevant cash flows for project evaluation.

8.2 Identifying Incremental Cash Flows in Capital Budgeting

8.2.1 Identifying Incremental Cash Flows

| Project Evaluation | Accounting Statement |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not all cash flows related to a project are relevant and will be used in the capital budgeting analysis. Failure to include all relevant cash flows or including non-relevant cash flows in the NPV analysis will result in the NPV being overstated or understated and can lead to an incorrect capital budgeting decision. When determining whether a cash flow is incremental, the key question to ask yourself is whether the cash flow would occur if the project were not accepted (if the answer is yes, the cash flow is not incremental).

This section outlines some guidelines in identifying relevant cash flows. The most important types of cash flows are discussed in the next section.

8.2.1.1 Cash flow categories

In this course, we cover five major categories of cash flows:

- Sunk Cost

- Opportunity Cost

- Side Effects

- Financing Costs

- After-Tax Cash Flows

A sunk cost is a cost that has incurred or is already committed to, and is thus a cost that will occur regardless of whether the company accepts or rejects the project. A sunk cost is not incremental with respect to the decision to undertake the project and should not be included in the analysis. Capital budgeting is related to future investment and any costs that were incurred in the past are not relevant.

Example: Walt Disney

Walt Disney conducts a preliminary survey and hires a consultant to help estimate demand and cash flows for a potential new park and resort. The consultant’s report will be used to generate cash flow forecasts for the computation of NPV so that Disney can decide whether to proceed with the new park and resort. The fee for the consultant should not be included in the initial outlay for NPV calculation because the company will still have to pay the fee for the consulting work performed, whether or not it decides to build the new park and resort. In other words, the consultation fee is not an incremental cash flow when evaluating whether the new park should be built.

When assets already owned by the company are used in a new project, the use of these assets represents an “opportunity cost”. By deciding to use the asset for the new project, the company is giving up the opportunity to use that asset for another project (or the opportunity to sell the asset). Opportunity costs are measured as the value of the next-best alternative use of the asset (often the market value of the asset). Opportunity costs are not necessarily out-of-pocket costs or costs that require a cash payment. We include and add the opportunity costs as a cost at the time they occur, if the resources used in the project could be used for alternative value-creating activities.

Example: Merlo

Merlo is considering whether to expand. It is looking at opening a new store in a shop already owned by Merlo but is currently rented out for $75,000 per year. If Merlo does not launch the new store, they will receive rent of $75,000 per year. If Merlo does launch the new store, they will not receive rent. The lost rent must be included in the cash flow computation for the new store because it represents a lost opportunity or opportunity cost.

Side effects or the impact of the project on the sales of another existing product line should be included in the cash flows relevant to the new project. The impact can be good or bad as launching a new product can increase or decrease cash flows generated from the existing products. When the impact is a loss of sales in another product line, we call it “erosion” or “cannibalized sales”. Not all lost sales are side effects, though. Often sales will be lost to competitors if updated products are not launched. So the appropriate consideration when measuring a side effect is the difference between projected revenue from the old product once the new product is launched and projected revenue without the new product.

Another common side effect occurs when expansion results in economies of scale or cost savings in other product lines. This is often called synergies. For example, a product that doubles the number of packing boxes needed to ship products may qualify the company for a volume discount on all packing boxes, not just those used for the new product.

Example: DVD Rent Co

DVD Rent Co is investigating an online streaming project that enables their customers to subscribe to videos online rather than using DVDs. The new project will reduce the DVD rental revenue relative to projected revenue without the online streaming product. Should this reduction of the DVD rental revenue be included in the incremental cash flows for the online streaming project? YES. DVD Rent Co’s cash flows as a whole will be reduced by the erosion of the DVD rental revenue.

In capital budgeting decisions, interest expense or any other financing costs such as dividends are not included in the cash flows. The rationale is that the project should be judged on its own, not on how it will be financed. Interest costs to the company are included in the interest rate used to compute present value (discount rate) and NOT the cash flows.

Example: Soulara

Soulara is a plant-powered nutrition program which includes meal-delivery service, using sustainable and local ingredients in composing the meals. Thus far, they have focused on meals for lunch and dinner only. They are deciding whether or not to also start offering breakfast options. If they undertake this new project, they will need to take on debt to finance the initial investment into a new large kitchen facility. Should the interest payments be included when evaluating the new project?

NO, financing costs such as interest expenses are not included in capital budgeting. They are considered by discounting the incremental cash flows at the cost of capital.

Taxes that have to be paid (or received) as a consequence of undertaking the project should be included in a project analysis, and therefore we consider after-tax cash flows in capital budgeting. The tax effects in a project may come from the taxes that are applied on the additional taxable income generated by the project as well as on the gain/loss of selling the fixed assets when the project is concluded or terminated. After-tax cash flows represent what is available to distribute to investors as dividends or interest. Because the project will generate additional taxable income for the company, the relevant tax rate is the rate that applies to the next dollar of income (also known as the marginal tax rate). In Australia, the company tax rate of 30% applies to large companies (turnover in excess of $50m) and 26.0% (25.0% from FY22) applies to small companies. Unless the project pushes total company turnover across the $50m threshold, you can just use these rates as the marginal rate.

Example: Sea World

Sea world is a marine animal park in the Gold Coast, Queensland, which promotes conservation through education and the rescue and rehabilitation of sick, injured or orphaned wildlife. It also offers a range of attractions such as rides and animal exhibits. It is currently considering adding another ride to the park, which is estimated to generate an additional EBIT of $5 million per year. If the company has an annual turnover of $150 million, what tax rate should Sea World use to calculate after-tax cash flows for the new ride?

30%, as the company is considered large (>$50m threshold).

Exercises

8.3 Calculating After-tax FCF for a Project

8.3.1 Calculating After-tax Free Cash Flow (FCF)

In calculating the after-tax FCF, we need to consider the yearly incremental operating cash flows that result from the project. Additionally, after-tax FCF includes any incremental capital expenditures as well as any addition to working capital that are required for the project.

After-tax FCF calculation adopt a stand-alone principle which means that we evaluate each project’s investment, revenue and expenses independent from the company that owns that project.

A project's FCF is calculated as follows:

|

Formula |

|

|---|---|

|

Revenue |

XXX |

|

Less: Operating Expenses |

(XXX) |

|

Earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) |

XXX |

|

Less: Depreciation/Amortisation Expenses |

(XXX) |

|

Earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) |

(XXX) |

|

Tax (EBIT x tax rate) |

XXX |

|

Net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) |

(XXX) |

|

Add: Depreciation/Amortisation Expenses |

XXX |

|

Operating Cash Flows |

XXX |

|

Less: Capital Expenditures |

(XXX) |

|

Less: Additions to working capital |

(XXX) |

|

After-tax FCF |

XXX |

This video will talk you through the steps involved in calculating after-tax FCF.

Video: FCF Calculation 8.3.1 (YouTube, 10m3s)

As shown in the formula above, the After-tax FCF calculation involves six steps:

Step 1: Compute earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) by subtracting operating expenses from revenue. Include all incremental revenue and operating expenses. Be sure to include opportunity costs and side effects, and to exclude sunk costs!

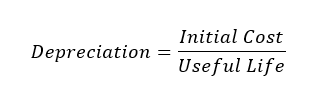

Step 2: Earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) is computed as EBITDA less depreciation/amortisation expenses. There are several depreciation methods allowed in accounting such as straight-line, diminishing-balance or units of production methods, but the only applicable method used on the tax return is relevant for the capital budgeting analysis. This is because we include depreciation in the analysis only due to its tax implication. In this course, all depreciation computations will be computed as the straight line depreciation with zero salvage value:

Depreciation is computed on tangible assets that have a useful life in excess of one year. For intangible assets (such as patents) the cost is spread over the useful life in the same manner. This is called amortisation.

Step 3: Net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) is computed as EBIT less tax. You compute tax by multiplying EBIT by the appropriate corporate tax rate. It is important to note here that interest expense is not deducted from EBIT when we calculate NOPAT. As discussed in section 8.2, financing costs such as interest expense are not relevant and should be excluded from the analysis. As discussed above, the financing expense is incorporated in the discount rate when we determine NPV later (we will discuss how to determine the relevant discount rate in Chapter 11).

Step 4: Add back the depreciation/ amortisation to get operating cash flows. This step may seem strange - up in step 2 we deducted the depreciation/amortisation, so why add it back now? Depreciation and amortisation are not cash flows, but they do reduce the amount of tax payable and tax is definitely a cash flow item! So, we need to deduct depreciation and amortisation to compute tax properly but add them back to compute cash flows. When we calculate NOPAT, depreciation/amortisation is included because the expense is deductible in calculating tax. However, we need to add back the depreciation/amortisation expense to NOPAT to get cash flow from operations. In other words, depreciation produces tax savings (tax shield) for the company.

Step 5: Subtract the incremental capital cash flows related to the project. Capital cash flows occur when we purchase or sell fixed assets that are required for the project. Typically, the company will purchase equipment or facilities at the beginning of the project, generating a large cash outflow (negative number) at the start of the project (at year zero on our timeline). The company may also sell equipment or facilities when the project ends, resulting in a cash inflow in the final year. It is important to compute this final year cash flow on an after-tax basis. We’ll talk more about the initial and final year cash flows in section 8.4.

Step 6: Subtract any addition to working capital. Launching a new product may require an investment in inventory, which will show up on the balance sheet and not in the income statement. Opening a new retail outlet will also require inventory as well as cash in the till. These balance sheet items aren’t free - they require a cash outlay. So, if the project requires an increase in current assets, we need to consider that investment in working capital when computing the free cash flows available. For a complex project, working capital may change every year as demand for the product changes. However, for this course, we will consider only simple projects where the amount of working capital required is constant over the life of the project. We’ll discuss working capital in more detail in section 8.4.

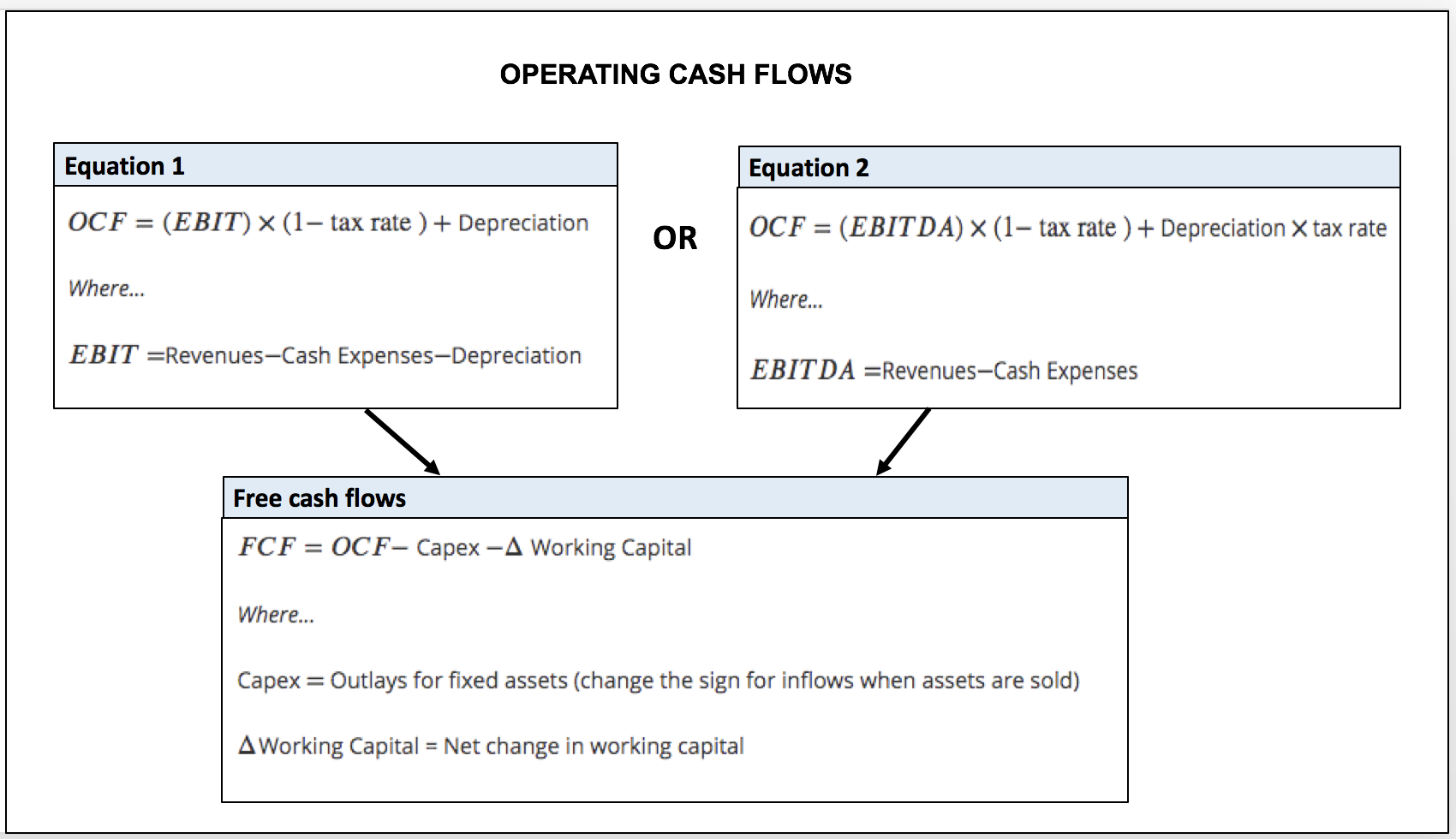

8.3.2 Formula for Operating Cash Flows (OCF)

The formula for operating cash flows (OCF - the result of step 4 ) can be written out algebraically in a few ways. Feel free to choose whichever method (the previous table or either of these equations) that makes the most sense to you. Once we have Operating Cash Flows (OCF), Free Cash Flows (FCF) is computed as shown below.

8.3.2.1 After-tax Operating Cash Flows Example

To illustrate the after-tax operating cash flow calculation, let’s go through the following example.

Radiant Ltd is considering launching a new lighting product that requires an initial investment in machinery and facilities of $300,000. These fixed assets will be depreciated straight-line to zero over their five-year useful life.

Radiant spent $10,000 for market research to help estimate demand for the new lighting. The project is estimated to generate $1,500,000 in annual sales for five years with annual cost of sales (materials and direct labour) of $1,000,000. The project will also require five additional employees in Radiant’s sales team, which will increase the company’s salaries and wages expenses by $250,000 per year. Also, production of the new product will take place in a warehouse that is currently being rented out for $30,000/year.

If the tax rate is 30%, what is the annual operating cash flow (OCF) for the first year of this project? (Since the question asks about year 1 only, you can ignore initial and final year cash flows).

View the following video on Operating Cash Flows and download the PDF handout if you wish to work alongside the example.

Video: After-tax operating cash flows (YouTube, 9m16s)

Handouts

Download Module 8 Example 1 Template and Solution (PDF, 871KB)

8.4 Initial and Final Year After-tax Cash Flows from Capital Transactions and Changes in Working Capital

8.4.1 Cash Flows - Incremental Capital Expenditures

In the previous section, we have focused the discussion mainly on the after-tax operating cash flows part of the after-tax free cash flows. As we have seen, operating cash flows correspond with items we might see in an income statement.

However, to convert operating cash flows to free cash flows, we need to adjust for changes in items on the balance sheet: fixed assets and working capital.

In this section, we will discuss in further detail how to compute:

- the after-tax cash flows related to the incremental capital expenditures, and,

- the addition to working capital that may be required for the project.

Many projects will require the purchase of facilities or equipment that will last for more than one year. A hotel considering adding a new restaurant to its facilities will need to purchase kitchen appliances, furniture and other fixed assets. These assets will be carried on the balance sheet rather than being treated as an immediate expense. Then, each year the book value of the asset will be reduced through the annual depreciation expense.

Finally, when the restaurant is no longer viable, the remaining fixed assets will be sold or scrapped. Remember that “cash is king”. The cash flows that result from these transactions are called “capital expenditures” or capex for short.

As with operating cash flows, only incremental cash flows are relevant. If the project uses assets the company already owns, the original cost of those assets is a sunk cost - no cash flow is required today. However, we need to consider what the alternative use is for those assets (that is, the opportunity cost).

We’ve already seen that when the alternative use is to rent out an existing warehouse, the rent we give up is considered an opportunity cost and is included in computing operating cash flow. Sometimes the next best option for existing assets is to sell them. In that case, deciding to proceed with the project means we’re giving up the opportunity to receive the value of the asset in cash today (that is, the opportunity to sell the asset), which must be taken into account as an opportunity cost in the form of an increase to capital expenditure.

Let’s Work Through an Example

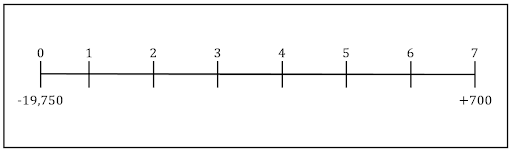

Fiji Resorts is deciding whether to open a coffee kiosk in the lobby. The space where the kiosk would be built currently contains furniture that cost $2,000 and could be sold for an after-tax cash flow of $250. The kiosk fitout will cost $20,000 and can be depreciated straight-line over a 7 year useful life. After 7 years the kiosk will be obsolete. The used equipment can be sold after 7 years for $700 (net of tax). What are the relevant capital expenditure cash flows?

In year zero (now) Fiji Resorts will spend $20,000 for the kiosk fitout and receive $250 from selling the furniture for a net out flow of $19,750. The $2,000 cost of the furniture is not a current cash flow - it’s a sunk cost. In 7 years, Fiji Resorts will receive a net cash flow of $700 from selling the used equipment. On a timeline:

Check Your Knowledge

Fortitude, Inc. is planning to set up a new factory. The factory will be built on a land that was bought 5 years ago for $6 million. When the land was purchased the company had planned to build an office building, but they were unable to complete that project. The land is currently vacant and has been on the market for six months.

A prospective buyer recently offered $10 million for the land. The costs for building the factory is $28 million. The land requires grading before it is suitable for construction and the grading cost is $1.5 million.

What is the proper cash flow amount to use as the initial investment in fixed assets when evaluating this project?

8.4.2 Calculating Final Year Cash Flow

Incremental cash flows related to capital expenditures can also take place at the final year of the project due to the residual value or the salvage of the fixed assets. Buildings or equipment used in a project often have some residual value at the end of the project, even if these assets have been depreciated down to zero. When evaluating a project, we need to take this residual value into account -- but, we need to be careful to include only the actual cash we will get to keep from selling the asset.

When an asset is sold, we need to determine whether that sale generates any taxable income and thus related tax liability. Clearly, if you buy an asset for $1,000 and sell it for $1,500, you have made a profit - and the (Australian) tax office will want its share. Your profit is $500 (=$1,500-$1,000), and tax at 30% would be $150.

You have received $1,500 in cash, but you owe a tax of $150 - so your after-tax cash flow from the sale is $1,500 - $150 = $1,350.

But how does that work when an asset has been depreciated? Think back to the accounting entries that are made when depreciation is recorded. One side of the entry is the depreciation expense and the other side of the entry is an accumulated depreciation account on the balance sheet. This accumulated depreciation account offsets the book value of the asset. If we buy an asset for $1,000 and have accumulated depreciation of $200, the net book value of the asset (i.e. cost less accumulated depreciation) will be $800.

When you make the sale you receive $1,500 in cash. At the same time, you are selling it for more than what it is worth on the books, and that is what you need to pay tax on. The gain on your sale is the sales proceeds (=$1500) minus the book value of the asset (=$800), which is $700. Since this is recorded as a profit on our income statement, tax will increase by $210 (30% of $700).

You’ve received $1,500, but you owe the ATO $210, so your net after-tax cash flow is $1,500-$210=$1,290.

More generally, the after tax cash flow on the sale of fixed assets is equal to the sales proceeds (cash received) less any tax due on the gain (or loss). The tax due on gain (or loss) is computed as gain (or loss) times the applicable tax rate. Gain or loss is computed as sales proceeds less book value. And book value is computed as original cost less accumulated depreciation.

Net Salvage Cash Flow = Proceeds - (Proceeds - Net Book Value) x tax rate

where, Net Book Value = Cost of asset - accumulated depreciation

In this case a profitable company will get a tax benefit from the loss. The loss will offset some of the company’s other taxable income and reduce the company’s tax liability relative to what it would have paid if the asset had not been sold. In this case the after-tax cash flow will actually be greater than the cash received for the asset.

Continuing with our previous example, assume you now sell the asset for $500 instead of $1,500. Given the book value of the asset is $800, you will make a loss of $300, which can be used to offset other taxable income. The tax savings is $90 (30% of $300). As a result, the net after-tax cash flow is $500 + $90 = $390.

8.4.3 After-tax Salvage Cash Flows - Worked Example

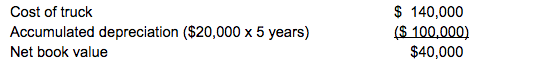

Inada Mining requires a heavy duty truck for a planned 5-year project. The cost of the truck is $140,000 and the useful life of the truck is 7 years. That is, tax regulations allow depreciation to be computed on a straight-line basis down to a zero salvage value over 7 years, even though Inada only plans to own the truck for 5 years. At the end of five years, the company expects to sell the truck for $50,000. If the company faces a 30% tax rate, what is the after-tax cash flow from selling the truck?

Solution: The cost of the truck is $140,000. Since the truck must be depreciated over 7 years, the depreciation expense for the truck is $20,000/year ($140,000/7 years). The book value of the asset is calculated as follows:

As shown above, the net book value of the truck is $40,000. Further, the sales proceeds of the truck after 5 years is $50,000. The net after-tax cash flow from selling the truck after 5 years is calculated as follows:

[latex]Net\:Salvage\:Cash\: Flow = Proceeds - (Proceeds - Net\: Book\: Value) × tax\: rate[/latex]

[latex]= 50,000 - (50,000 - 40,000) × 0.3[/latex]

[latex]= 47,000[/latex]

Exercise

Calculate net salvage cash flow Fantastic Frogs

Fantastic Frogs has decided to purchase a new chocolate frog molding machine.

The machine costs $150,000 and tax regulations require that it be depreciated straight-line to zero over a ten year life. Fantastic Frogs expects to sell the machine for $60,000 after seven years when their new high volume chocolate frog molding technology is ready for production.

What is the after-tax cash flow that Fantastic Frogs will receive when the machine is sold in seven years? The relevant tax rate is 30%.

8.4.4 Addition to Working Capital

Launching a new product may require an investment in inventory, which will show up on the balance sheet and not in the income statement. Opening a new retail outlet will also require inventory as well as cash in the till. These balance sheet items aren’t free - they require a cash outlay. So, if the project requires an increase in non-cash current assets (or decrease in current liabilities), we need to consider that investment in working capital when computing the free cash flows available.

For a complex project, working capital may change every year as demand for the product changes. However, for this course we will consider only simple projects where the amount of working capital required is constant over the life of the project.

So, how do we determine the cash flow from working capital?

Cash is required to fund changes in working capital only. If we need to have $2,000 in the cash registers over the life of the project, then that means we have to put $2,000 aside at the beginning of the project (at time zero on our timeline). After all, the cash needs to be available in the cash register before we can start selling our product.

We needed zero additional working capital before starting the project, and $2,000 in working capital when the project begins - a change of +2,000 in working capital and a cash flow of -2,000. Each subsequent year, we still need $2,000 in the cash register. There’s no change in the level of working capital required, so there’s no additional cash flow.

At the end of the project, we no longer need to have cash in the cash register, so the $2,000 will come back into the general bank account and can be used for other investments (or to pay dividends). So, at the end of the final year, we have a change in working capital requirements of -2,000 and a cash flow of +2,000.

Generally, if the working capital requirement is constant over the life of the project there will be a negative cash flow (outflow) in year zero and an equal positive cash flow (inflow) in the final year of the project.

Remember from your accounting course that working capital is defined as current assets less current liabilities. Therefore, the change in working capital can be determined as the changes in the company’s cash and cash equivalents, accounts receivable, inventories and accounts payable that are required by the project.

Working capital (WC) is calculated as follows:

[latex]WC = Cash\: and \:Cash\:Equivalents + Accounts \:Receivable + Inventories - Accounts\: Payable[/latex]

Test Your Knowledge: Working Capital

Amazing Androids Pty Ltd is opening a new retail outlet. It estimates that the new outlet will require the following investment in working capital:

Cash float of $1,000

Investment in inventory of $30,000

Increase in accounts payable to suppliers of $3,000

Increase in accounts receivable from customers of $5,000

What is the cash flow amount to be included in year zero when evaluating Amazing Androids’ new retail outlet?

8.5 Tying it all Together

8.5.1 NPV Relevant Cash Flows-Extended Example

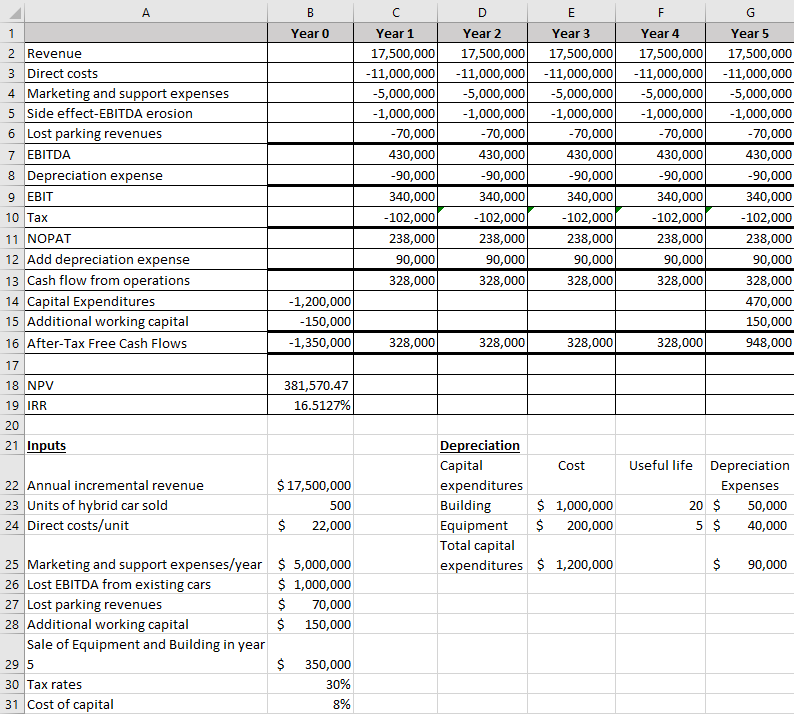

So far, we have discussed relevant free cash flows that consist of 1) incremental after-tax operating cash flows, 2) incremental capital expenditures and 3) an addition to working capital as the consequences of undertaking the project. In this section, we will analyse a more comprehensive example that ties all the concepts above and relates those concepts with the NPV and IRR calculation discussed in Chapter 7.

- BMX Ltd., a car manufacturer is currently evaluating a proposal to introduce a new hybrid car model that is more environmentally and economically friendly. The project’s duration is expected to be 5 years and after 5 years the project will be terminated since the company will run a new fully electric car project. An intensive feasibility study costing $250,000 has already been completed. Based on the feasibility study, the company expects to sell 500 units of the new hybrid car per year. Annual revenue is estimated at $17,500,000 for the next 5 years. The company estimates that the direct cost for each car is $22,000/unit. The marketing and support expenses will be $5 million per year. If the new hybrid car is introduced, EBITDA from the existing cars will fall by $1 million per year.

- The production of the new car will be conducted in a new plant to be built on land already owned by the company. The land was purchased 10 years ago for $750,000 and has been used for a commercial car park. The annual EBITDA generated from the car park is $70,000. The cost to build the plant will be $1,000,000 and the building value is expected to fall to $300,000 after 5 years. For tax purposes, the building must be depreciated straight line over a 20-year life with no salvage value. The plant also needs equipment for the manufacturing process that costs $200,000. It is expected that the equipment will be depreciated straight-line to zero in 5 years. At the end of the project, the equipment will be sold for $50,000. The new project requires $150,000 of working capital starting immediately.

- The working capital will be recovered at the end of the 5 years. An additional financing cost of $750,000 per year will be required to help fund this project. The corporate tax rate is 30%. BMX plans to use a cost of capital of 8% to evaluate this project.

With the above information, consider the following:

- What is the NPV of the project?

- What is the IRR?

- Should the company proceed with the project?

Video: FINM1416_22 Relevant Cash Flows-Extended Example Part 1 (YouTube, 11m51s)

Video: FINM1416_23 Relevant Cash Flows-Extended Example Part 2 (YouTube, 4m58s)

Video: FINM1416_24 Relevant Cash Flows-Extended Example Part 3 (YouTube, 8m21s)

8.6 Computing NPV and IRR in Excel

8.6.1 NPV and IRR Extended Example

The video below demonstrates how to calculate NPV and IRR for the extended example in section 8.5 using Excel.

Video: Extended example Excel 8.6.1 (YouTube, 10m22s)

If you prefer to read instead of watching the video, please read the below between the lines.

---------BEGINNING OF TEXT VERSION----------

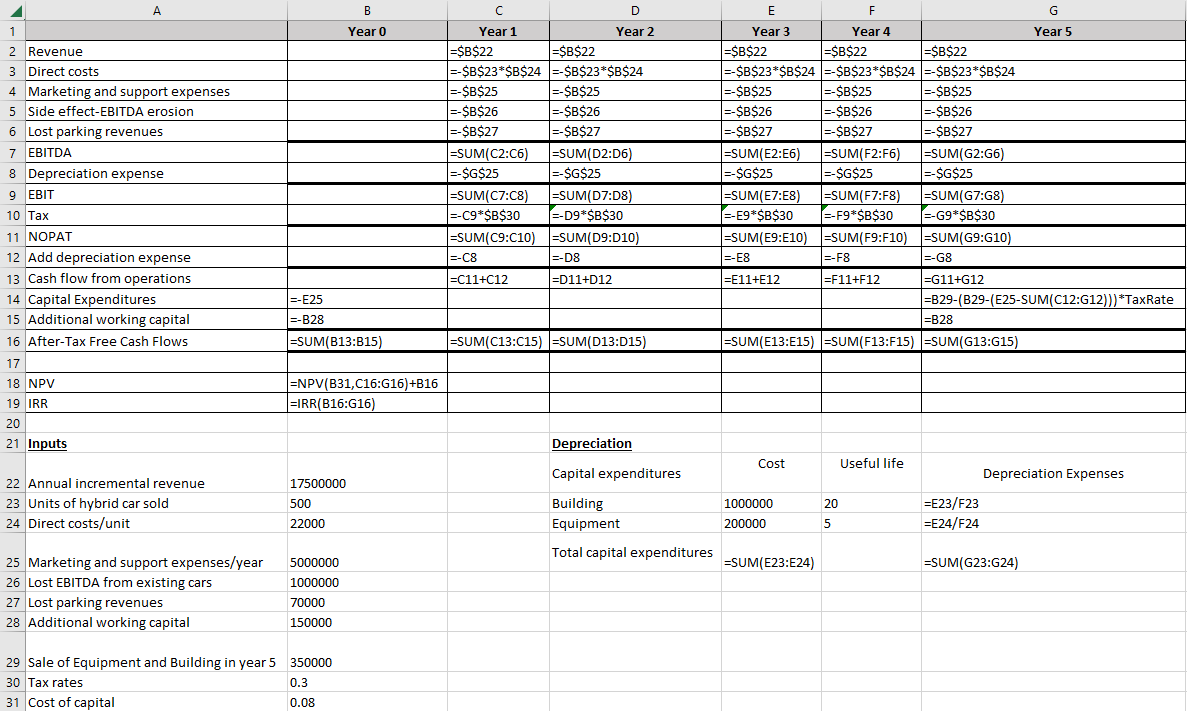

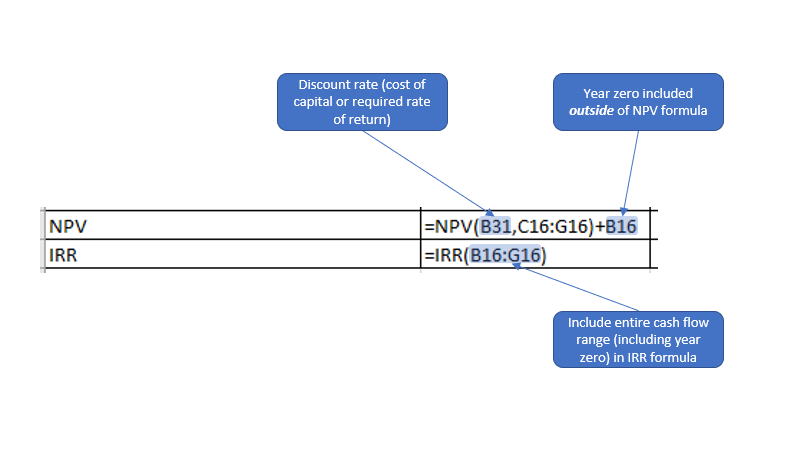

The table below shows how to solve for NPV and IRR for the extended example in section 8.5 using Excel. Excel has a specific function for determining NPV and IRR:

NPV : =NPV(discount rate, range of cash flows) + Initial Investment

IRR : =IRR(range of cash flows)

It is important to note here that the range of cash flows in the NPV formula using excel excludes year 0 cash flow (initial investment). The year 0 cash flow is added separately. However, in determining IRR, all cash flows including year 0 cash flow are included in the IRR formula.

Further, as shown above, it is recommended to list all the inputs that will be used in the calculation separately. By doing this, we can change any of the inputs (assumptions) used such as units of hybrid car sold or the direct costs/unit and see how the change affect NPV and IRR. This is especially important when we want to perform sensitivity analysis, scenario analysis or goal seek analysis for a particular project. These analyses will be discussed in Chapter 9.

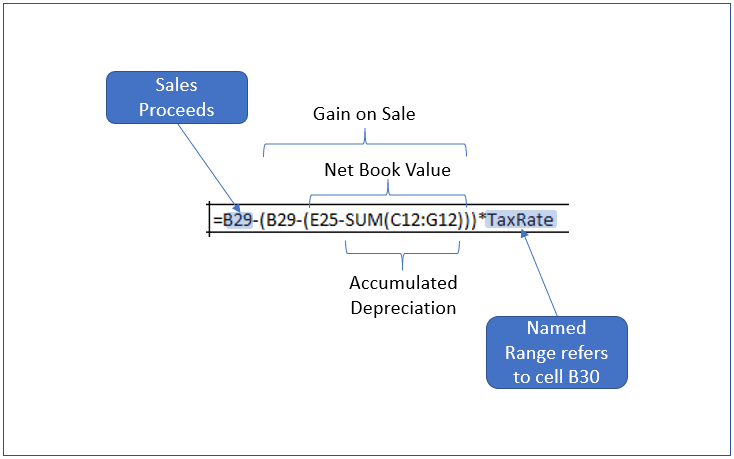

The year 5 capital expenditures excel formula is explained below. Notice how the named range "TaxRate" makes the formula easier to read.

---------END OF TEXT VERSION----------

Download

Download Excel Template (xlsx, 24KB)

8.7 Summary and Conclusion

8.7.1 Summary

In this chapter, we mainly focus on the calculation of incremental after-tax free cash flow in evaluating a project. When determining whether a cash flow is incremental, the key question to ask is whether the cash flow would occur if the project were not accepted. If the answer is yes, then the cash flow is not incremental.

We also discussed five major categories of cash flows:

- Sunk cost

- Opportunity cost

- Side effects

- Financing costs

- After-tax cash flows

It is important to understand how each of these cash flows is treated in calculating the free cash flow for a project. Lastly, in calculating the final year cash flow, we need to be careful to include only the actual cash we will receive from selling the asset, which means we need to consider the tax implications. If an asset is sold for higher price than the book value, then the gain on sale is taxable and tax should be deducted from the cash proceeds.

8.7.2 Key Formulas

Operating cash flow:

[latex]OCF = EBIT × (1-tax rate) + Depreciation[/latex]

where…

Or

[latex]OCF = EBITDA × (1-tax\:rate) + Depreciation × tax\:rate[/latex]

where…

Free cash flow:

[latex]FCF = OCF - Capex - ∆Working\:Capital[/latex]

where…

Final year cash flow:

[latex]\text {Net Salvage Cash Flow}=\text{Proceeds} -\text{ (Proceeds - Net Book Value)} \times \text{ tax rate}[/latex]

[latex]\text {Net Book Value}=\text{Cost of asset} - \text {accumulated depreciation}[/latex]