12 Corporate Sustainability & Sustainable Finance

12.1 Introduction

Upon completion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- evaluate the implications of the “challenges of the century” for business and finance

- describe different theories of the purpose of a firm and identify the differences between them

- critically evaluate theories taught in this course

- explain the concept of sustainability and how it is used in business and finance.

In this chapter, we will continue the discussion from Chapter 1 on theories of business purpose, and you will learn about the basis of corporate sustainability and sustainable finance. This chapter will also look at the objective of the firm in relation to sustainability.

Before we go into the sustainability in a business and finance context, we will first cover some major challenges humanity is facing today and in the future.

12.2 Challenges of the Century

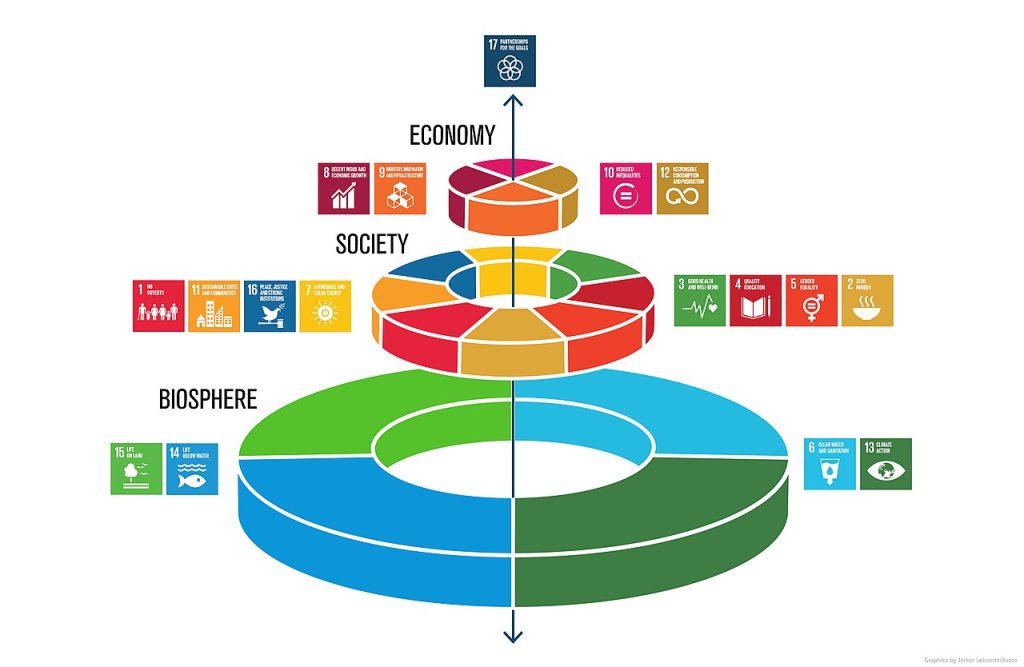

In Chapter 1 we mentioned the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which identify a range of goals to achieve prosperity whilst protecting the planet. To jog your memory, they are depicted below in three categories; environmental (biosphere), social (society) and economic. For societies and economies to thrive in the long term, and thus can “sustain” (sustainable), a highly functioning natural environment and healthy equitable social system is required.

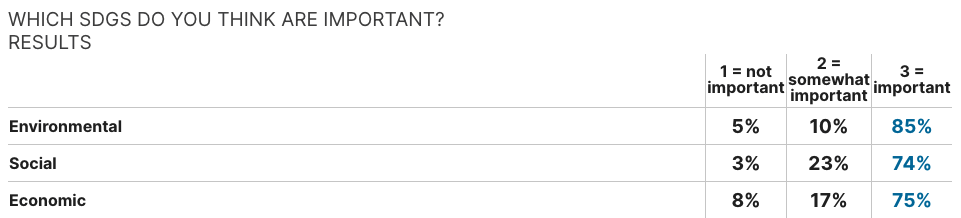

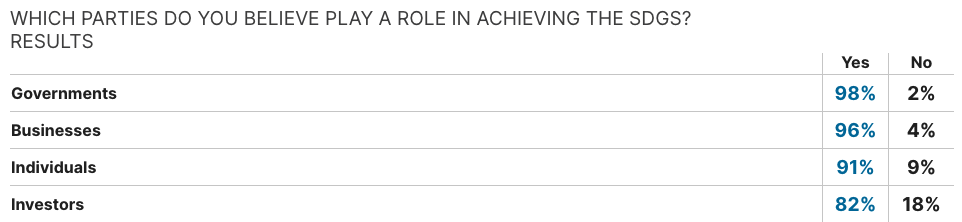

Most of you agreed that all SDGs are important:

and that most parties in society play a role in achieving SDGs:

Thus, most of you agree that financial markets (albeit less than other actors) and businesses play a key role in tackling challenges we face as a society.

In this first section of Chapter 12, we provide a brief history and overview of developments in different environmental and social systems and how they are connected, in particular we look at:

- Socio-economic trends

- Earth System trends

In this background section we draw information from other sciences, such as earth system and environmental science. Before continuing, here are a few questions to think about:

What are some of the challenges of the century?

What are some of the issues humanity has to deal with or has to face in the next century?

12.2.1 Socio-economic Trends

Since the Industrial Revolution, we invented machinery to replace manual tasks, and discovered new chemical processes and power sources (e.g. coal). Whilst these inventions led to an increase in population and economic development, the figure below demonstrates that a much more rapid growth occurred since the 1950s. There were unprecedented and exponential increases in our social and economic (socio-economic) systems.

The Anthropocene website contains more information on the major changes that have occurred in key trends since 1950.

Exercise

Go to the Anthropocene website and click on The Great Acceleration. What are some of the great accelerations we have seen in socio-economic systems? In our earth system?

Answer:

Socio-economic system:

- world population

- real gdp

- foreign direct investment

- urban populatin

- primary energy use

- fertilizer consumption

- large dams

- water use

- paper production

- transportation

- tele-communication

- international tourism

Earth system:

- carbon dioxide

- nitrious oxide

- methane

- stratospheric ozone

- surface temperature

- ocean acidification

- marine fish capture

- shrimp aquaculture

- coastal nitrogen

- tropical forest loss

- domesticated land

- terrestrial biosphere degradation

Of course these are just examples, and there are many more!

One of the most obvious challenges is related to the exponential increase of population. This is because people live longer and on average have more than 2 children. The human population has more than doubled in the past 50 years, from less than 3 billion to over 7 billion, resulting in humans exerting even more dominance over other species. However, it is expected that increased education and opportunities for women will result in a stabilisation of the global population in the future.

Economic growth (GDP) has also reached unprecedented levels since the 1950s, leading to substantially more wealth and higher levels of welfare. However, these increases are mostly concentrated in OECD countries. Economic systems have become global, where the wealth of countries is linked to other countries. We have collectively moved to cities, and many people have access to primary energy such as electricity and transport, allowing further economic development. We produce unprecedented levels of food which has led to the increased use of fertilisers and water. We travel more and have more electronic devices than ever before. Did you know that only 15 years ago one of the lecturers of the course had to select which message to delete when the number of messages on her Nokia phone reached the limit of 20 messages?

The Anthropocene website has more information on the socio-economic development.

Example: Mobile Phones and Telecommunications

In the 1950s, people were not using mobile phones yet, they only became part of our daily lives around the 2000s. This explains for example why telecommunications have risen significantly in the past 20 years. The same holds for tablets, laptops, and smart watches. These devices require energy to be produced, charged, and recycled, and have led to increased data use and storage. These devices are just one example of many aspects of our lifestyles that require large amounts of energy and resources. The way we currently produce, use and dispose our products has resulted in exponential changes in our environment. A great challenge is to decouple our social and economic growth from negatively impacting the life-support systems our planet is fortunate to have.

12.2.2 Earth System Trends

Our explosive socio-economic developments have led to large changes in our natural environment. That humans impact the natural environment is nothing new and has been documented since humans have wandered the earth. Now, however, it is happening at a much larger scale and is impacting some important life-supporting systems on regional, national and global scales.

The Great Acceleration figure above demonstrates the effect human activities have had on various key environmental indicators. Atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gasses (carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane) have exponentially increased, caused by, among other things, fossil fuel combustion for energy (carbon dioxide), increased deforestation (reducing the earth’s uptake of carbon dioxide), agricultural processes including life-stock (nitrous oxide and methane), and other industrial processes. Ozone depleting gases have increased through the increased use of certain chemicals (e.g. CFC in refrigerators), which has led to ozone depletion. Strict regulation has stopped the use of these chemicals and has stabilised the amount of ozone depleting gases. Increased greenhouse gas emissions has led to ocean acidification. Our human activities have also led to increased over-fishing, tropical forest loss, and loss of species. This has dire ramifications not only for our environment, but also for those companies and small businesses that rely on the environment for the running of their business, namely in the sectors of agriculture and tourism. This New Scientist article describes how climate change is already affecting the tourism sector around the Great Barrier Reef.

12.2.3 The Great Acceleration

12.2.3.1 When did Humans Begin to Affect the Earth’s Systems?

As we have seen, humans have moved from impacting the environment on a local scale to now becoming a geological force that is affecting the way the whole planet operates. Scientists are saying we have moved into a new geological epoch, the “Athropocene” – an epoch where humans are the driving force of changes in the environment. Some propose that this era started centuries ago, when we started smelting metals, traces of which we see in the Greenland ice core. Others argue that this started in the industrial revolution, when we dramatically increased our use of fossil fuels.

A TED talk on the “Anthropocene” (YouTube, 18m15s) by renowned earth system scientist Professor Will Steffen is available.

In geological terms, according to scientists, we now already live in the Anthropocene (instead of the Holocene), a geological epoch in which humans are the dominant force on the natural environment. In other words, humans are the primary cause of permanent planetary change. This epoch is characterised by the fact that planet is now outside of its natural limits. From sole participants, humans became the dominant creatures in the Earth, having an influence on the oceans, landscape, agriculture, and animals. Human activities have caused fundamental changes in the way the Earth is behaving, and it could be a full-scale catastrophic change.

Exponential growth in social and environmental changes has been evident since the industrial revolution. As we saw in the previous graphs however, a massive expansion of the human enterprise has occurred since the 1950s, and this phenomenon is what scientists call the great acceleration. It refers to the era in which human activities are changing environmental systems at unprecedented scales and levels.

One of the main inventions that have allowed us to “unleash” the human enterprise was the invention of “fossilised energy”, also known as fossil fuels. These fossils that have been built up underneath the earth for millions of years, provide a cheap, powerful, reliable, and convenient energy when combusted. This energy source allowed humans to undertake economic activities more efficiently, such as:

- Converting and plowing land (globally, 85% of land has been impacted by humans in more than one way!)

- Manufacturing and transporting of products, many consuming energy themselves (e.g. cars, phones, laptops..)

- Construction,

- Cutting down trees at a faster rate (for example, 50% of Australian forests have been cut down since European settlement)

- Building enormous fishing boats (also trawling the seas with huge nets and systems),

- Reforming the coastal zones,

- Changing the Delta systems of rivers,

- Travelling large distances,

What can 1 litre of oil provide to you? It allows you to drive for around 10-11kms, carrying the weight of your car and propel it forward, even on steep hills. What would happen if you were to try and push the car yourself for 10-11 kms? It would be beyond difficult. This highlights the power of only 1 litre of oil. It is enormously condensed energy and one that has powered business and prosperity for a long period of time.

Unfortunately, there is a side effect. During the process of fossil fuel combustion, carbon dioxide (CO2) is produced. CO2 is a greenhouse gas, which traps heat in the atmosphere. Why is this a problem? There is a natural level of greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere that keeps the Earth warm, at exactly the right climate for humans to live and develop in. If humans are releasing CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere every year, the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere increases, making the planet warmer. However, is a warmer planet bad for us?

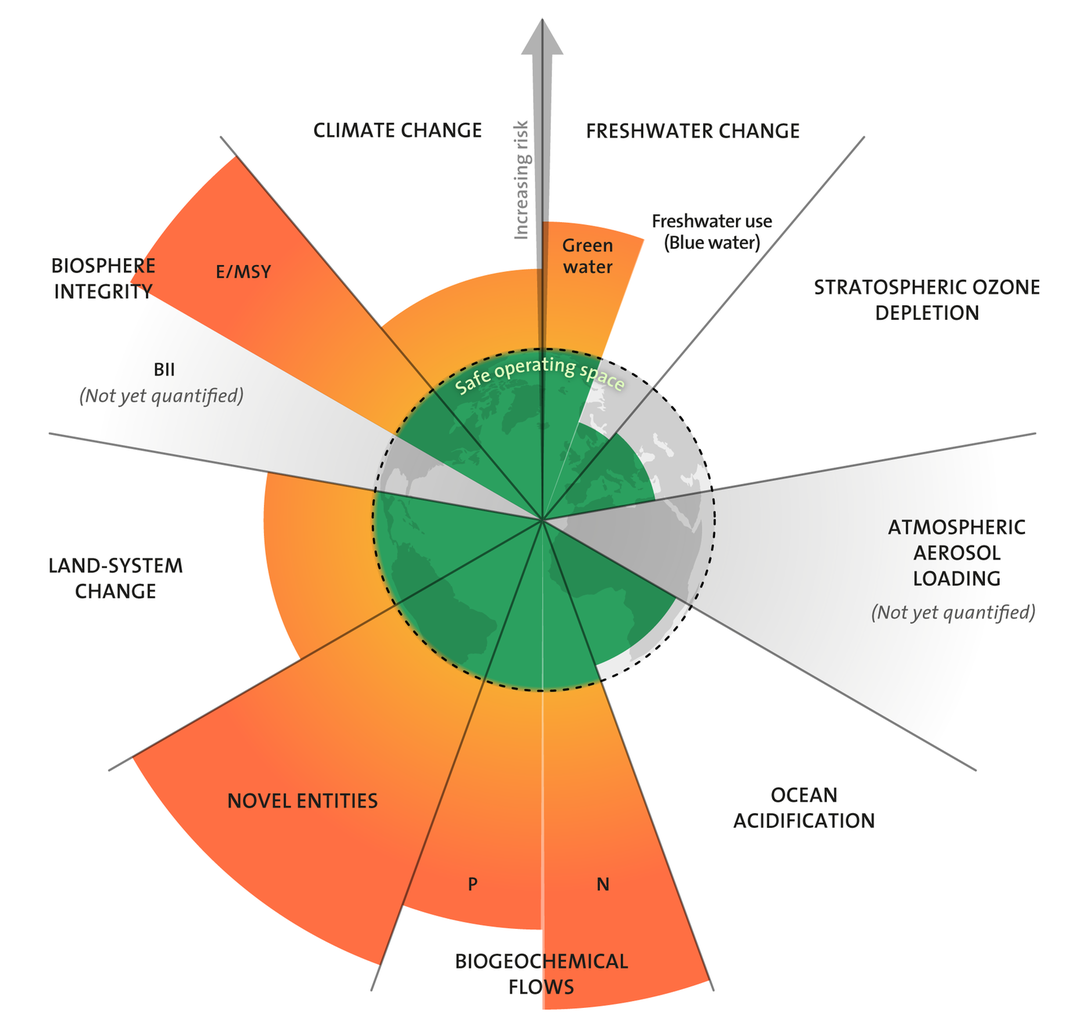

12.2.4 Planetary Boundaries

For humans it is important to know: “which earth systems are humans impacting? which systems are important in providing a “safe operating space for humanity”? How much can we change these systems before it becomes unsafe for humans?”. The planetary boundaries framework aims to answer these questions based on the most sophisticated scientific knowledge and evidence to date (for example work that has been published in prestigious journals such as Nature and Science).

The framework identifies nine interlinked, but different, systems: climate change, novel entities, stratospheric ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol loading, ocean acidification, biochemical flows, freshwater use, land-system change and biosphere integrity (see above figure). Humans are dependent on these systems and humans have an impact on these systems at the same time.

The framework concerns itself with the level of anthropogenic (human caused) changes that can occur, so that the risk of destabilisation of the Earth is likely to remain low. Generally, it is an indication of what a safe operating space is for global societal development and identifies the scientific limits to important planetary systems, which if transgressed, would pose a high risk of irreversible change in the Earth’s stability, tipping it out of the safe Holocene state.

Crossing the identified limits is considered high risk because:

- Changes can be extreme, rapid and irreversible when tipping points are reached,

- It is costly for humans to adapt and,

- There are limits to how much change humans can adapt to.

For some systems we can have an idea of system limits, such as climate change. For other human impacts on the environment, we know that they pose a risk but we do not know the limit. For example, micro plastics or silicon fall into the category of novel entities. These materials do not naturally exist: they were created by humans. Although somewhat beneficial, the reverse effect of these materials depends on the level of their concentrations and usage. Now, there are over a hundred thousand man-made chemicals that do not naturally exist. We know that the too many novel entities poses a risk, but we do not know exactly how much is too much.

For other systems, such as biochemical flows (nitrogen and phosphorus cycles), which are mainly affected by the increasing level of agriculture and land use, we know how much is too much on a regional level. The heavy reliance on certain chemicals has already caused acidification of rivers (i.e. “dead-zones”) on regional scales. Whilst all planetary boundaries are important, the two core planetary boundaries are climate change and biosphere integrity. The reason for this is that these two systems could tip the earth into a new, unsafe state and also have a significant impact on the other boundaries.

12.2.5 Case Study: Biosphere Integrity

Biosphere integrity refers to the quantity and quality of biodiversity. It is very similar to the concept of diversification that you learnt in this course. The more plant and animal species that inhabit the planet, and the better the quality (“function”) of these species, the more resilient and better the health of our ecosystems is. Currently we are facing extinction rates that are 100-1000 higher than usual. We have thus exceeded the planetary boundary of limiting extinction rates to 10 extinctions per million species per years (=10 times the usual rate). However, when making tough choices on which species are most important to concentrate our efforts on conserving, we need to look at the function of species in our ecosystems.

For example, bees would definitely be on our priority list! Bees pollinate about 70 percent of the world’s food. Although very small in size, bees are doing very important services for us (for free!!), and are highly functional. This means that if bees go extinct, unprecedented problems would occur. The functional diversity of specifies are different. This means that some species provide greater “function” to the ecosystem than others. Perhaps losing some types of mosquitoes might not be that bad though?

12.2.6 The World Economic Forum

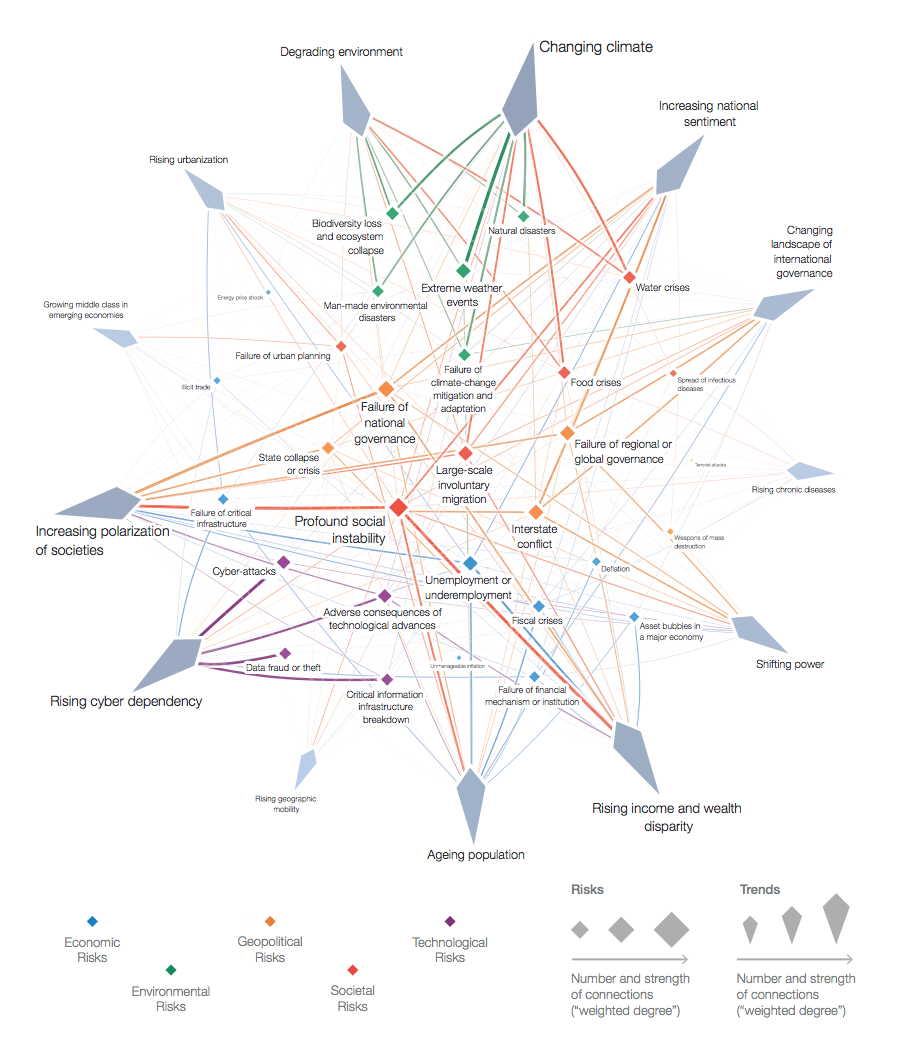

So far, we have focused on socio-economic and environmental developments. This has provided you with an introduction of how systems are vastly interrelated. To understand and help solve challenges it is important to take a systems perspective that acknowledges complexity and interrelatedness, as not to “shift” challenges by creating a new one to solve another.

A useful demonstration of how challenges are related across different systems, and how to prioritise these challenges, can be found in the yearly ‘global risks report’ by The World Economic Forum. It reports the interrelatedness of risks, referring to economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal and technological risks. It details the number and strength of connections between different risks and trends. Environmental risks dominate global risks in terms of both impact and likelihood.

This figure below demonstrates the interlinkages between the different types of risks, and how one problem is connected to other problems. Consistent with the planetary boundaries framework, climate change is identified as a strong driver of increased environmental and social risks.

Whilst climate change has had an impact on several environmental issues, such as biodiversity loss, natural disasters (extreme weather events), it will increasingly lead to social issues such as food or water crisis, and large-scale immigration. It will also dramatically alter our economies and businesses, regardless of whether we rise to meet the challenge or not. Thus, ultimately climate change is a long-term socio-economic issue that, if is not tackled, will have catastrophic implications for socio-economic systems.

12.2.7 Challenges of the Century – Summary

In this section of Chapter 12, we have covered how recent rapid developments in socio-economic systems have led to unprecedented changes in important earth systems. This presents us with unique challenges for humanity in this century. One challenge is to decouple our socio-economic activities from negatively impacting planetary systems on which long-term human development depends. At the same time, there are social challenges such as poverty and income equality that are important to be considered. In the next section we focus in on the challenge of climate change.

12.3 Climate Change

12.3.1 Introduction

In this section of Chapter 12, we focus on the challenge of climate change. Climate change has increasingly been pushed up the agenda internationally given the urgency of the issue. As we learnt in the previous section, climate change is one of the key earth systems that can, on its own, push the earth into an undesirable state for humans to develop in. If climate change is not tackled, it could even lead to humans becoming extinct. Tackling the challenge will require many changes in the way we see and do business and finance. Mark Carney, prior governor of the Bank of England, said recently at the 26th Conference of Parties (COP, 2020) meeting on climate change:

“The objective for the private finance work for Cop26 is simple: to make sure that every private finance decision takes climate change into account. [..] Achieving net zero-emissions will require a whole economy transition – every company, every bank, every insurer and investor will have to adjust their business models”.

If we act now, Mark Carney says it “could turn an existential risk into the greatest commercial opportunity of our time”. Note that what Mark Carney stated can be applied to any challenge: challenges can also be considered as opportunities, it depends on one’s perspective as to how we approach them. What he is suggesting here is that if companies increase their investment in research and development that helps us transfer to a low carbon economy, they will most likely be rewarded with healthy bottom lines in the not-too-distant future.

12.3.2 Climate Change: Science

In this TEDxNASA (YouTube, 17m 21s) video, Bruce Wielicki gives an overview of some of the key facts and impacts of climate change.

12.3.2.1 How Does the Climate System Work?

The way the climate system works can be associated with simple budgeting. There is an income, and expenses, and the balance of the two.

In the climate system, there is sunlight, which is the incoming resource or energy that keeps heating up the planet. This energy leaves the system through infrared radiation – this is something that you do not see with your eyes, but it feels similar to fire, if you are close to it. At the same time, there are greenhouse gases (often expressed as a CO2-equivalent) blocking the heat from escaping, giving us a nicely habitable earth.

Thus, there is energy coming in, and energy leaving the system, which has a balance, and this is the energy budget of the planet. This determines the climate on the planet. Before the industrial revolution, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere was 280 parts per million (ppm), but through our anthropogenic activities we kept adding greenhouse gases every year, increasing the amount of heat retained, and resulting in a concentration of 419ppm in October 2023.

Exercise

You can find historical carbon dioxide – and other greenhouse gas – levels on the NASA website.

What was the concentration of carbon dioxide in 1960?

Answer:

Around 320ppm.

Has the concentration of carbon dioxide changed since we wrote this pressbook?

Answer:

Yes. When checking again in January 2024 it had risen to 320ppm, so when you are checking now it will likely be higher.

The more carbon dioxide there is in the atmosphere, the more heat is trapped and the warmer the planet gets. The main sources of anthropogenic CO2 emissions are fossil fuel combustion, cement production and flaring.

Exercise

Here we are going to do our first exercise of looking up information provided by the IPCC. To make it easy we will give you the direct link to where you can directly see all the figures contained in the AR5 2014 synthesis report. Click on “graphics”, and open Figure 1.5.

What is the other category of global anthropogenic CO2 emissions?

Answer:

Forestry and other land use

Between 1750 and 1970, approximately how many GtCO2 were emitted cumulatively for the two categories of anthropogenic CO2 emissions?

Answer:

Forestry and other land use: around 500GtCO2

Fossil fuel combustion, cement production and flaring: around 400GtCO2

And between 1750 and 2011?

Answer:

Forestry and other land use: around 700GtCO2

Fossil fuel combustion, cement production and flaring: around 1300GtCO2

12.3.3 What is a Cloud Feedback?

Scientists were interested in the way climate change impacted the Earth’s systems decades ago. The earliest climate models were built in the 1970s.

These models analysed cloud feedback, to see the impact of change in temperature. For example, if the global cloud cover is changed by 1 percent, it triggers dramatic changes in the sensitivity of the climate system (Note: Bruce Wielicki has been studying cloud feedback for the last 30 years!).

For a more accurate representation of this change, satellite data was analysed, in different wavelengths (or colour of light). This allowed scientists to compare the amount of green vegetation, the brown deserts, the snow, the ice and the clouds, and the thermal emission that is infrared up to space. This method contributed to a better understanding of the climate system and facilitated the prediction of future trends. There are many examples like this for the studying of oceans and other planetary systems.

Some of the reliable sources to look at and find reliable information about climate change are:

- skepticalscience.com – common questions about climate change answered referencing peer-reviewed literature

- American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) – established in 1848, gathering scientists around the world, spending hundreds of years on climate system questions.

- American Geophysical Union (AGU) – established in 1919, with 50,000 members in 137 countries.

- American Meteorological Society (AMS) – established in 1919, with 14,000 members.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – group consists of thousands of scientists around the world, who are working to analyse how the climate system is changing and what the risks and occurring issues are.

Note: in academia, peer-reviewed articles are considered legitimate sources. Peer-reviewed articles have undergone significant criticism and questioning by other academics in the field, and are only published when all criticism and concern have been addressed to the highest standard.

12.3.4 Climate Change: Impacts

12.3.4.1 What are the Impacts of Climate Change?

Human activities are estimated to have caused 1.2C of global warming since pre-industrial levels. The impacts of climate change are already being felt around the world, we are already experiencing species extinction (flora and fauna slowly disappearing) and more extreme weather events (more frequent and more intense), just to name a few.

Exercises

The IPCC report summarizes the concerning impacts of climate change in their 5 reasons for concern. Particularly in the 2018 IPCC special report on 1.5C it outlines the differences in impacts of 1.5°C vs 2°C warming. We do not expect you to remember these impacts – this is merely to show you how a changing climate causes risks for socio-economic systems. Every country will be exposed to a different extent to these risks (More information on the impacts on Australia).

It is very useful to be able to find information in IPCC reports.

- Go to ipcc.ch

- Click on Reports, then click on “Global Warming of 1.5°C”.

- In the section “summary for policy makers” click on “explore graphics”.

- Click on “Figure SPM.2.”

What are the Five Reasons for Concern? Do the levels of impacts and risks associated with these reasons change from 1.5°C vs 2°C warming?

Answer:

- RFC1: Unique and threatened systems

- RFC2: Extreme weather events

- RFC3: Distribution of impacts

- RFC4: Global aggregate impacts

- RFC5: Large scale singular events

Yes, the risk levels increase for all of these impacts.

The bottom bars of the figure show the level of impacts and risks to various natural, managed and human systems. List them and identify those most at risk at 1.5°C.

Answer:

- warm water corals

- mangroves

- small-scale low-latitude fisheries

- arctic region

- terrestrial ecosystems

- coastal flooding

- fluvial flooding

- crop yields

- tourism

- heat-related morbidity and mortality

Risks are highest at 1.5°C for warm-water corals, small scale low-latitude fisheries , arctic region and coastal flooding.

12.3.5 What can be Done to Stop the Temperature Increase?

12.3.5.1 The Paris Agreement

Based on the overwhelming scientific evidence on climate change, most nations around the world have signed the “Paris Agreement”, which is a commitment to keep temperatures well-below 2°C warming compared to pre-industrial levels. Crossing 1.5°C-2°C will substantially increase the risk of setting off feedbacks that will lead to irreversible and catastrophic changes to our planet. For example, crossing 2°C would substantially increase the risk of melting the icecaps in Greenland, which if melted, will release huge amounts of methane (a strong greenhouse gas). The suddenly increased level of greenhouses gases would then accelerate climate change. As the earth is one big complex interconnected system, there are many such feedbacks.

Even though the Paris agreement has been signed by most nations, current commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are not sufficient to stay below the 2°C threshold. In fact, current commitments will lead to warming of at least 2.6-3.1°C (Rogelj et al., 2016). Find out how on track your country is.

12.3.6 Climate Change: The Way Forward

12.3.6.1 Carbon Dioxide Emissions Pathways

To have a more than 50% chance of staying below 1.5°C, cumulative emissions need to be kept within 480 GtCO2 from 2018, which is also referred to as the “remaining carbon budget”. Currently, we emit around 41 GtCO2 globally every year. This means that if we did not reduce emissions, we would exceed the budget before 2030.

Exercise

The IPCC outlines different pathways to reduce emissions society can follow, all resulting in net zero emissions by around 2060.

- Go to ipcc.ch

- Click on Reports, then click on “Global Warming of 1.5°C”.

- In the section “summary for policy makers” click on “explore graphics”.

- Click on “Figure SPM.3B.”Have a look at the different pathways and their assumptions.

Which pathway has the highest use of Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS)? How much cumulative Carbon Capture and Storage needs to be used by 2100 in this pathway? How many bioenergy crops in 2050? How much land is this compared to, for example, China?

Answer:

Pathway P4 requires the largest amount of BECCS, requiring cumulative CCS of 1218GtCO2 by 2100 of which 1191 GtCO2 being BECCS. This means that, on average, around 15GtCO2/yr needs to be captured and stored (compare this to annual anthropogenic emissions being around 40GtCO2 in 2020!!). This pathway requires 7.2 million km2 being used for bioenergy crops in 2050, this means a land size the equivalent of the majority of China being covered in crops (China’s land area is about 9.6 million km2).

All scenarios require a fundamental shift in the energy sector away from fossil fuels, requiring large investments in renewable energy and storage solutions and a loss of value of existing fossil fuel assets. The scenarios also all rely on AFOLU (Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use) emissions to go to zero and turning negative using Carbon Dioxide Removal technologies such as afforestation (and perhaps increasing the population of whales?) that remove carbon from the atmosphere. Three of the four scenarios also include removal of carbon through Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS). These technologies however have many limitations, one of which is a high cost.

In the first scenario (P1), there is low population growth, with reduced energy demand and rapid decarbonisation, which is depicted by the rapid decrease of fossil fuels. In contrast, the last scenario (P4) depicts high population growth and high consumption patterns, where population remains reliant on fossil fuels. Although there is a reduction in the amount of fossil fuels (grey area), it still remains largely present for the next few decades. This scenario will need to rely heavily on technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS).

12.3.6.2 Human Development Index

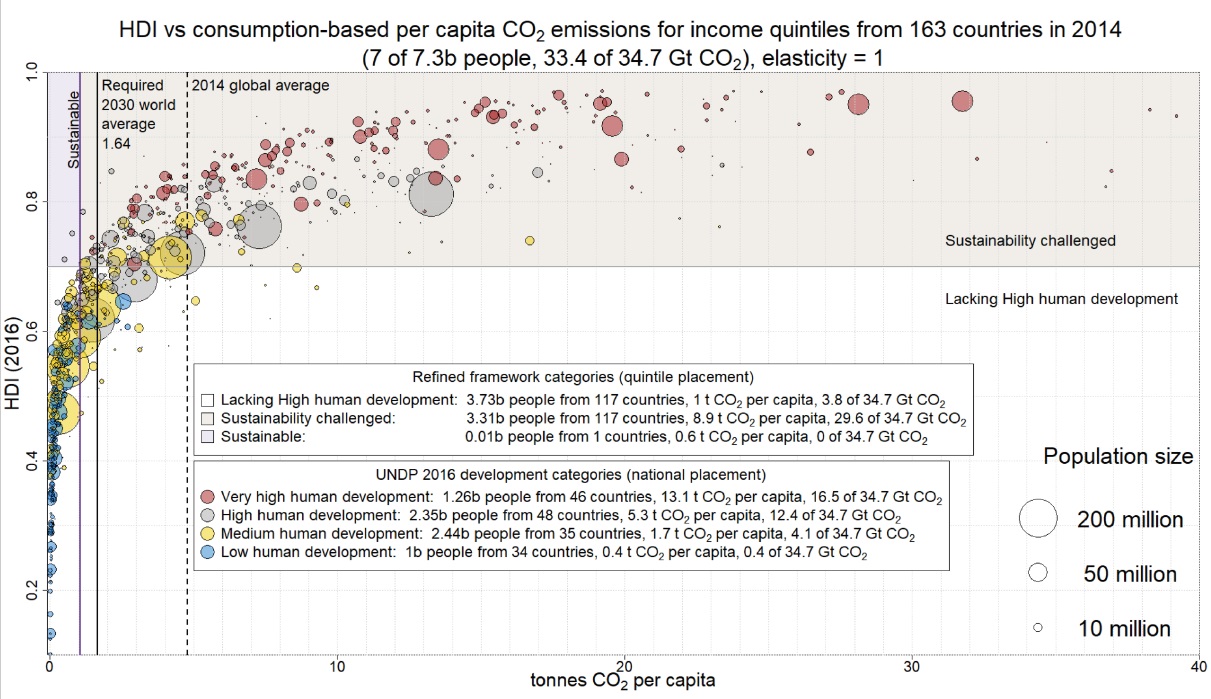

The climate challenge can also be seen as a “dual-challenge”. The figure below looks at the correlation between HDI (Human Development Index) and consumption-based per capita CO2 emissions, considering different income quintiles.

In the graph you can see a clear trend: the higher the development of a country, the higher the carbon emissions per capita. For example, if you live in Australia on an (relatively low) income of around AUD$25,000 per year, then your carbon footprint is estimated to be around 13 tonnes of CO2. This amount can vary depending on a couple of factors, including one’s travelling habits (e.g. international flights) and diet (e.g. vegetarian or meat-based diet).

If everyone in the world would get an “equal” carbon budget, how much would this be? In order to stay within a 2°C consistent carbon budget, everyone in the world would have 1.64 tonnes of CO2 allocated per person to emit in 2030. The challenge for developed countries is therefore to maintain a high HDI, but decrease the emissions per capita. For developing or underdeveloped countries the challenge is quite different, as they currently have very low CO2 levels per capita. Their challenge is to increase their HDI without increasing their emissions. An important element of the Paris Agreement is that there are “common but differentiated responsibilities”. This means that because developed countries have emitted by far the largest portion of emissions, and have benefited from this greatly, they have a greater responsibility in mitigating climate change, including provide Climate Finance to poorer countries.

12.3.6.3 Carbon Intensity Pathways of Sectors: How can we Decarbonise Different Sectors?

In order to contribute to the CO2 reduction process, industries have to adopt significant transformations. Have a look at Table 2 of this Nature Climate Change article which provides a summary of the unit reduction certain industries have to achieve in order to achieve the sustainability targets.

For example, in the case of power generation, the global average was 591 g CO2 per kWh 2011 and to stay within a global carbon budget consistent with staying below 2°C, this amount should be reduced to 28.7 by 2050. Power generation currently predominantly relies on the use of fossil fuels. Ways to decarbonise power generation can be achieved with renewable energy or nuclear power. However, both options carry certain risks or drawbacks. An increase in renewables has to be paired with investment in energy storage and smart systems. There is some exciting research ongoing by UQ researcher Dr. Jake Whitehead on using electric vehicles as portable energy storage systems, i.e. “battery-on-wheels”.

12.3.7 Climate Change as a Tragedy of the Commons

Climate change is a classic example of a ‘tragedy of the commons’. This occurs where a common pool of resources is overexploited. Globally, individual entities (each country, each company, and each individual) have a self-interest to consume or produce more than their ‘fair share’ of greenhouse gas emissions, which has led to a suboptimal state of our common climate. Think “why should I fly less when all my colleagues or friends don’t? Why should I consume less energy when everyone else doesn’t?” (for more information on the tragedy of the commons, please have a look at this science article).

Solving this issue requires collective action, and it is essential to recognise the importance of governance, ethical dimensions, equity, value judgments, economic assessments and diverse perceptions and responses to risk and uncertainty. Hardin (1969) argues that there is no technical solution to the tragedy of the commons. It requires the education of people, and a sense of moral responsibility to acknowledge the problem and to reduce the production of greenhouse gases.

Climate change was first addressed internationally as a major issue in the 1970s, in an IPCC report. Since then, there have been numerous international negotiations on how to solve it, mainly evolving around which country has to do what, which highlights this case as a collective action problem.

Did you know?

There is an increasing area of the law that deals with the rights of people in regards to climate change.

For example, in the Netherlands, there was a lawsuit brought by citizens, who sued their government for not taking enough action against climate change. They won the first case, which was appealed, and then they won again. This initiated an international breakthrough in terms of law, encouraging Courts to mandate that the Governments take the required actions.

Overall, this section has put a lot of emphasis on climate change, as an example of one of the challenges of the century, but of course, we are facing many other environmental and social issues.

Arguably, tackling Climate Change and other challenges require collective action (with a critical mass of actors taking action) and an extension of a moral responsibility by a multitude of actors. In the next sections, we briefly revise the different theories of the responsibilities of business in society. In section 12.3, we will discuss the limitations of some of the concepts that we have taught in the course, and discuss recent developments in both business and finance in relation to challenges of the century.

12.4 Theories of Business Purpose

12.4.1 Introduction

Let’s Recap!

In Chapter 1 we introduced different theories of business purpose. Please go back to Chapter 1 if you need a refresher on the different theories. The theories are also summarised in short below:

12.4.1.1 Shareholder Theory (Friedman 1970)

Shareholder theory holds that the sole goal of a business is to maximise shareholder wealth, and that all corporate actions and investments should be evaluated on this basis. Friedman believes that it is not the corporate manager’s role to pursue anything charitable, or incur costs for preventing environmental or social harm. However, Friedman does believe that profit maximisation should incur “while conforming to the basic rules of society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom.” and “without deception or fraud”. Corporations are independent of political views, and one’s individual views of morality ought to be expressed through the democratic system and supported by their own consumption decisions. Company profits should be given to shareholders as a dividend, who could then decide, individually, what charitable contributions to make, if any. This does not mean that charity was not important, rather that companies are not the appropriate vehicle as they do not have a comparative advantage in giving to charity.

Friedman’s view on the shareholder theory has received a lot of criticism, highlighting that the idea of shareholder primacy and the ”duty” to maximise profits is promoting an excessively short-term perspective, often at the long-term expense of the society, the economy and/or the company (see for example this article in the Financial Times). For the first time since 1987, the Business Roundtable, consisting of CEOs from the largest US corporations moved away from Friedman’s view and refined the purpose of the corporation “to promote an economy that serves all Americans”, which is consistent with Stakeholder Theory (next).

12.4.1.2 Stakeholder Theory (Freeman, 1984)

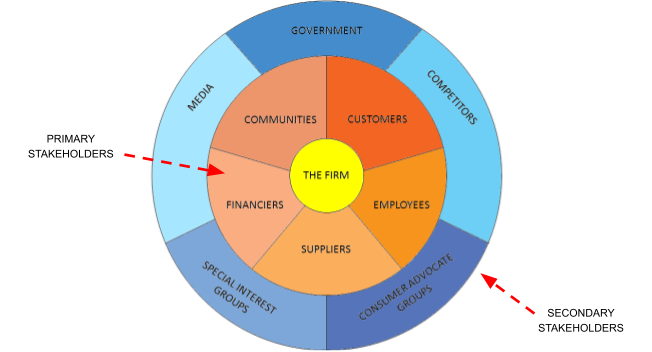

Freeman focuses on stakeholders, where stakeholders include any group/s that affect or are affected by the realisation of an organisation’s purpose (Freeman, 1984).

According to stakeholder theory, the role of the manager is to maximise value for all stakeholders, so not only shareholders, but customers, employees, the broader community and others. In contrast with the shareholder theory, the stakeholder theory focuses on value, and not wealth (in this view, wealth is only part of the value). Businesses need to maintain a positive relationship with society and their environments in order to operate effectively. Failure to do so can destroy value for their stakeholders and ultimately affect a business’s ability to operate in the long term.

Stakeholders are employees, communities, suppliers, customers, the environment, shareholders, and the government. Most of them have contractual relationships with the firm. In general, the stakeholders should be viewed as equals, without no superiority or trade-offs.

This will lead to “good business” and long-term value creation for all stakeholders (including shareholders).

All stakeholders do not have the same influence on an organisation, which is why they are separated into these two categories. Primary stakeholders (orange pieces of the pie chart) are those individuals or groups who have a greater influence on the organisation and they are at utmost importance because the business relies on them for long-term survival. For example, what happens if customers stop buying the products?

Is there really a difference between Stakeholder theory and Shareholder theory? After all, maintaining a good reputation with society, customers and employees, and operating the business in an environmentally responsible manner could actually be consistent with maximising shareholder wealth. In fact, this is the conclusion of one school of thought known as “Enlightened Friedmanites” (that is, followers of Milton Friedman with an enlightened point of view). However, there is still a difference based on motive. Proponents of Stakeholder theory have the motive of enhancing value for all stakeholders from an ethical standpoint, while Enlightened Friedmanites are still focusing on shareholder wealth.

12.4.1.3 Shareholder Value Myth (Stout, 2011)

Stout disagrees with Friedman but for reasons different from Freeman. She frames her discussion around managerial duty in a legal and historical context. She states that corporations are legal entities that own themselves and shareholders have contracts with the firm that gives them limited rights. Firms can pursue multiple objectives and aim to do at least sufficiently well at each rather than maximising only the wealth objective. Shareholders are different (i.e. there is no “single shareholder value”), all participate in society, and are likely to have social and environmental concerns. Thus, managers should be allowed to conduct the business in a socially and environmentally responsible way.

Stout also shows that since the late 1900’s, the focus on shareholder wealth only (also called shareholder primacy) has actually led to a decrease in investment in R&D and financial returns, suggesting that a satisficing approach, which creates value on multiple fronts, may not only be better for shareholders, but for society as a whole.

12.4.1.4 Shareholder Welfare Theory (Hart and Zingales, 2016)

Hart and Zingales argue that corporations should maximise shareholder welfare rather than wealth.

They talk about three conditions necessary for shareholder welfare maximisation to be a superior business objective to shareholder market value maximisation. These are:

- profit-making and damage-generating activities of companies are inseparable

- government does not perfectly internalises externalities through laws and regulations

- shareholders are pro-social

The authors also state that if shareholders pro-social preferences are sufficiently heterogeneous, then due to collective choice issues, market value maximisation may be a “second-best” objective.

12.4.2 Corporate Social Responsibility

12.4.2.1 CSR – The Big Questions

12.4.2.1.1 What is Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)?

CSR argues that corporations are responsible for their actions, just like an individual. In other words, decisions made by managers (i.e. business decisions) are not exempt from ethics. It is similar to stakeholder theory in that it considers a wider responsibility than just to shareholders. However, CSR is different from stakeholder theory in motivation. CSR starts with the firm and looks outward to determine responsibility, whereas stakeholder theory starts with looking at the firm from outside to determine the relevant stakeholders and then work out how the firm should behave. For example, a firm may decide not to incur some extra costs to not pollute a river: did it do this not to harm stakeholders (stakeholder theory), or because it was the right thing to do (CSR)?

12.4.2.1.2 How is CSR Reported Within a Company?

Every company that is currently operating and is familiar with trends and current societal expectations now issues a CSR or sustainability report. This trend is mostly caused by shareholders demanding transparency and information on a companies’ CSR activities, recognising that engaging in environmental or social controversies can pose significant financial risks, whilst positive actions can increase reputation. However, it is common for companies to engage in ‘greenwashing’, where “positive” actions are highlighted and negative impacts are not mentioned. It may be, therefore, more interesting to ask “what is not being reported by the company?”. This is why independent information on what the company is doing is very important. This has given rise to sustainability rating agencies that rate companies on a vast range of ESG indicators.

12.4.2.1.3 Is CSR Similar to Philanthropy?

A distinction that should be noted is that CSR is different from philanthropy. This is important to note because Friedman’s thesis focused on charitable giving by companies. Philanthropy typically means donating money to a ‘good cause’, e.g. a charity, the arts or sports. However, while philanthropy can form part of a company’s CSR strategy, giving some money to charity is not the same as CSR. Sometimes it can even be used as a distraction from the company’s irresponsible activities. The firm’s CSR activities need to be integrated into the firm’s strategy and all of its activities. For example, do you believe that a retailer that knowingly purchases garments that were produced using child labour, and pollutes local rivers can be seen as “responsible” just because they donate 1% of their profits to clean energy projects? Or even when they support “related” project such as supporting an education project for children?

12.4.2.1.4 What is the Difference Between CSR and Stakeholder Theory?

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is very similar to stakeholder theory, in that it emphasises the need to focus on both shareholder wealth maximisation and the firm behaving responsibly (ethically). It is likely that the eventual outcome from a decision will be the same under CSR or stakeholder theory.

CSR, however, is different from stakeholder theory in its motivation. CSR starts with the firm and says, “What is the right thing to do in this scenario?”; looking outward to determine responsibility, whereas stakeholder theory starts with looking outside the firm to determine the relevant stakeholders and then works out how the firm should behave.

CSR is concerned with what the right course of action to take is. When differentiating between stakeholder theory and CSR, question whether the company did something to not harm stakeholders, or because it was the right thing to do.

Exercise

GoodHealth Inc. has just found out that their baby food product still contains traces of the harmful chemical asbestos, which can, in some cases, harm a babies’ health. In addition, its production facilities also often leach the chemical into a nearby lake in the small town in India where it operates. However, preventing the use of this chemical will require a new production process which is rather expensive. The financial manager of the company shows that keeping its current production processes is financially better than changing them, even considering a possible damage in reputation (who is going to find out anyway?) and paying for lawsuits. However, management decided that they were still going to change the production practices, because not doing so would substantially decrease value for its stakeholders. Is the firm applying CSR or stakeholder theory?

12.4.3 Corporate Sustainability

12.4.3.1 How are Corporate Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility Related?

Corporate Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility are often used interchangeably. However, technically speaking corporate sustainability is one step further than corporate social responsibility, and it falls under the umbrella of sustainable development. Sustainable development is defined as meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This includes the need for economic, social and environmental sustainability. It views firms as playing an active positive role in staying within planetary boundaries and meeting the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

12.4.4 Alternative Business Models

Whilst there seems to be an increased expectations and pressure for for-profit corporations to act socially responsibly, there has also been a rise in the number of social enterprises and not-for-profits.

What are Certified B Corporations? There is global growth in companies becoming certified B corporations. These corporations are legally required to consider the impacts of their decisions on their workers, customers, suppliers, community, and the environment. These are still for-profit, but have a clear commitment to creating value for all stakeholders first.

For example, have you heard about ‘Ben and Jerry’s? or ‘Who Gives a Crap?’ toilet papers?

‘Who Gives a Crap?’ is a Certified B Corp that pledges to spend a portion of revenue to build toilets in developing countries

What are not-for-profit organisations? Not-for-profit organisations exist to provide services for the community and measure their success in the social and environmental impact that they create. They do not exist to create a profit for their members. Many not-for-profit organisations (though not all), also apply for charitable status to provide a tax deduction for the individuals and companies that provide money to fund their charitable works.

Concept Check

In this section we have looked at different views of the firm’s role in society. You have already applied several of the theories in the first Workshop. We apply the theories to another real world situation below.

Merchants of Doubt

Merchants of Doubt is a book co-written by Harvard Professor Naomi Oreskes, which refers to companies actively spreading doubt on science so that they can keep selling their product (another book on this topic was recently published in the Oxford University Press called “The Triumph of Doubt”). A common and well known example is the tobacco companies. When cigarettes first hit the market, the tobacco companies released statements saying that health reports stating that smoking was harmful were all incorrect or falsified, because smoking is good for you, and you should buy cigarettes. All advertising and promotions propagated this standpoint – that cigarettes were good for you. This means that doubt was created about the science, which allowed tobacco companies to keep selling their products.

The exact same occurrence is happening with climate change. There is ample evidence that shows that fossil fuel companies are funding fake reports and fake news. Realistically, it is less expensive (in the short term) to fund fake research and reports, as well as pay groups to lobby against carbon emission legislation, than it is to pay for the actual carbon emissions.

There are various groups online (these are called the merchants of doubt) who present climate change as a fiction, or some political agenda. They intend to feed this uncertainty to people about climate change and trigger doubtful thinking and question what is reliable or not.

What should a corporate manager working for a fossil fuel producer do under each of these different theories? What would you expect the companies to do?

“If funding climate change denial groups to create “doubt” of science to the public and lobby against carbon regulation is cheaper than having to pay for the damage caused by their carbon emissions, the corporate manager should…”

What should a corporate manager do under the shareholder theory?

What should a corporate manager do under the stakeholder theory?

What should a corporate manager do under corporate sustainability?

What should a corporate manager do under the principles of CSR?

12.5 Critical Thinking Regarding Concepts Taught in this Course

12.5.1 Introduction

We have covered different theories of business purpose in the previous section, thinking critically about what the purpose of a business should be in society. In this section, we ask you to reflect on the limitations of theories taught in the course and what alternative tools are available to create a positive impact on overcoming the challenges of the century.

How do we measure success?

What are the ethical and environmental impacts of seeking only financial profit?

This is an opportunity for you to weigh up and determine your position or values as a manager.

12.5.2 Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT)

12.5.2.1 Modern Portfolio Theory (Module 10)

In Module 10, we learnt that Modern Portfolio Theory suggests that everyone should hold a combination of the risk-free investment option and the market portfolio to get a maximum reward-to-risk independent of your risk preference. Investing in the market portfolio provides the most diversification of risk.

But what happens if we all invest in a market portfolio, for example, the S&P500 or ASX200? What if investing this way is consistent with e.g. a 4°C increase in temperatures compared to pre-industrial levels? Should we still be investing in the market portfolio? What if investing in the market portfolio is consistent with increasing income inequality? Should we still invest in the market portfolio?

Discussion: Do you think investors have a responsibility to consider societal impacts of their investments? Yes or No?

Consider the example of Tesla. They are a for-profit company with a mission to accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy.

Tesla has been highly unprofitable, but what can it do to generate large sums of investment so that it can innovate and become more profitable? We are almost at the stage where renewables are overtaking fossil fuels, but we are not there yet.

What does this mean for Tesla? Who should help Tesla? Should the consumers or investors pay more for their product? For example, if consumers are willing to pay the price for Tesla, then Tesla will have more financial resources, and grow. Are the consumers the ones that should pay for an expensive car, or should investors also be willing to receive a lower return? Or should governments provide subsidies for green technologies? (and/or perhaps cut subsidies for polluting industries)?

Do you think that all stakeholders have a responsibility? Or do you think one group has more responsibility than another?

The following question is debated heavily in the literature: Is doing good also good for the bottom line?

Considering hundreds of studies, there is no clear outcome. Why? Because elements of ESG can increase financial performance, whilst others may not. For example, reducing environmental impact can be a lot cheaper, such as energy efficiency, reduced resource use and less waste. Other products and services might require a larger investment upfront or cost more. For example, plastic cups are not environmentally friendly but are much cheaper than glass and requires less time washing up. Solar energy also requires a high upfront investment, and depending on government support (or subsidies for fossil fuels) might be financially attractive or not.

Limitations of Modern Portfolio Theory: Are investors rational?

Are there other forms of return? Increasingly, investors do not want their investments to be associated with “unethical” practices, and sometimes want a social and/or environmental return in addition, even at a compromise of financial returns.

Is there a consideration of (long-term) societal impact of collective investing according to the MPT? From research we know that “the market portfolio” is far from being aligned with staying within the agreed 2°C global warming limit. In fact, a study showed examined an extremely well diversified portfolio of 30,000 publicly listed companies, and find it is currently aligned with a temperature of 3.4°C, well above the 2°C limit. Should we still invest in the market portfolio?

12.5.3 Discount Rates

Discount Rates: Why do we discount the future/use a discount rate?

“If we used the share market’s discount rate to value the lives of future Australians and if we knew that doing something would give lots of benefits now but would cause the extinction of our species in half a century, the calculations would tell us to do it.” (The Garnaut Review, 2011)

As you would have learnt in this course, a core principle in finance is the “Time Value of Money” – we prefer money sooner rather than later because we could earn interest on it. To capture this “Time Value of Money” we use a discount rate to convert cash flows from the future in today’s value. However, by using discount rates, an implicit assumption can be made on how much we value the future value:

1) The greater the discount rate, the less any future cost/benefits are worth today, and

2) The more distant positive or negative cash flows are, the less they are worth today.

12.5.3.1 Implications of Discount Rates on Climate Change

What do discount rates mean for the future in terms of climate change?

Tackling climate change would require large investments now, such that we still have a stable economy in the long-term. However, these long-term benefits are worth very little if we apply a discount rate, whilst the costs weigh very heavily as they would be incurred now. Vice versa, if we operate “business as usual” we would generate large profits now, but climate change will cause long-term costs in the future, which would be worth very little to us today.

By using the current market discount rate, there is an implicit assumption that, regardless of the investments we make as a society, the economy can keep growing at the same rate, i.e. current returns do not impact the ability to generate future returns. It thereby ignores the externalities and “the big picture” of how we are developing as an economy, and the consequences of this in the long term. In the case of climate change, the investments we make today have an impact on our ability to have a stable economy in the long-term. In a sense, using discount rates automatically values cash flows for future generations lower than those for present generations.

But can we use the market discount rate? Many economists argue that besides the need for pricing carbon, there is a need for a social discount rate for projects involving future economic damages caused by current actions. A survey shows that most economists suggest a discount rate of 2% for climate change related activities. Other economists, like Martin Weitzman, argue it would be worthwhile to go beyond economic analysis and that catastrophic climate change should be avoided at all costs.

Discount rates are important in climate discussions, as they determine what people should pay now per ton of carbon to pay for damages in the future. This is also referred to as the social cost of carbon. It is a question of economics and ethics, as physical science cannot answer this.

12.5.3.1.1 Example

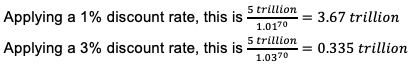

To get a better understanding, assume that if we continue business as usual, climate damages at the end of the century will be $5 trillion (note: it will be much more, but for arguments sake, let’s keep it at $5 trillion).

You can see that a slight difference in discount rate can have huge implications of how much we value climate damages. Let’s say that taking no action on climate change generates a benefit in today’s terms of 0.5 trillion, then the calculations for a 3% discount rate would tell us take no action on climate change. This is because the benefit of 0.5 trillion is more than 0.335 trillion – and our economic growth (expected at 3%p.a.) will generate more wealth in the future that it costs us to deal with these damages in the future.

Note that this example was greatly simplified, but it illustrates the sentiment of the quote at the start of the paragraph.

Estimates of the social cost of carbon vary widely. This study suggests the cost of carbon should be at least $125 per tCO2, whilst other estimates range from $34 – $1,079 per tCO2 for emissions in 2010, and from $77 – $1,875 per tCO2 for emissions in 2050. Using the $125 per tCO2, how much extra would you need to pay for a long-haul return flight from Brisbane to Europe (6t CO2) if you had to pay for the associated social cost? You would have to pay at least $125×6=$750.

Note: if the social cost of carbon is implemented, it does not necessarily lower emissions to 2°C. This should be done through a carbon price, aiming to induce behaviour change to reduce emissions to the levels agreed upon in the Paris Agreement.

12.6 Sustainable Finance

12.6.1 Sustainable Investing

We have talked about the role of business, but what is the role of investors in creating a sustainable socio-economic system? What do you find important when making financial decisions? What do you find important when investing? Do you consider ethics when choosing a bank account? Superannuation portfolio?

KPMG (2019)’s Shareholder Values: Shareholder Value report released the following results from a survey they conducted.

| Importance of Total Overall Factors (Extremely/Very Important) | Total | < 30 years old | 31-40 years old | 41-50 years old | 51-60 years old | > 60 years old |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Behaviour | 54% | 66% | 57% | 49% | 51% | 55% |

| Environmental Sustainability | 40% | 59% | 51% | 32% | 38% | 35% |

| Pays fair share of taxes to Australia | 63% | 65% | 63% | 57% | 61% | 68% |

| Treats employees well | 55% | 67% | 57% | 49% | 51% | 57% |

| Value beyond making a profit | 52% | 65% | 55% | 48% | 46% | 53% |

According to the results presented, millennials in particular (highlighted in pink) find the majority of factors very important when making financial decisions.

12.6.1.1 A Note on Banks

Also in the banking industry there is an increase in customers wanting their bank to act responsibly and to invest ethically. The Global Alliance for Banking on Ethical Values is an independent network of banks, using financial services to deliver sustainable economic, social, and environmental development (see for example this video on Triodos Bank – the Founder of the Alliance). The alliance started 30 years ago and they have 54 financial institutions as members, 50 million customers, and $163.4 billion USD assets under management. In Australia, Bank Australia is the only bank that is a member of this alliance.

12.6.2 Sustainable Investing Framework and Tools

12.6.2.1 Sustainable Investment-Framework

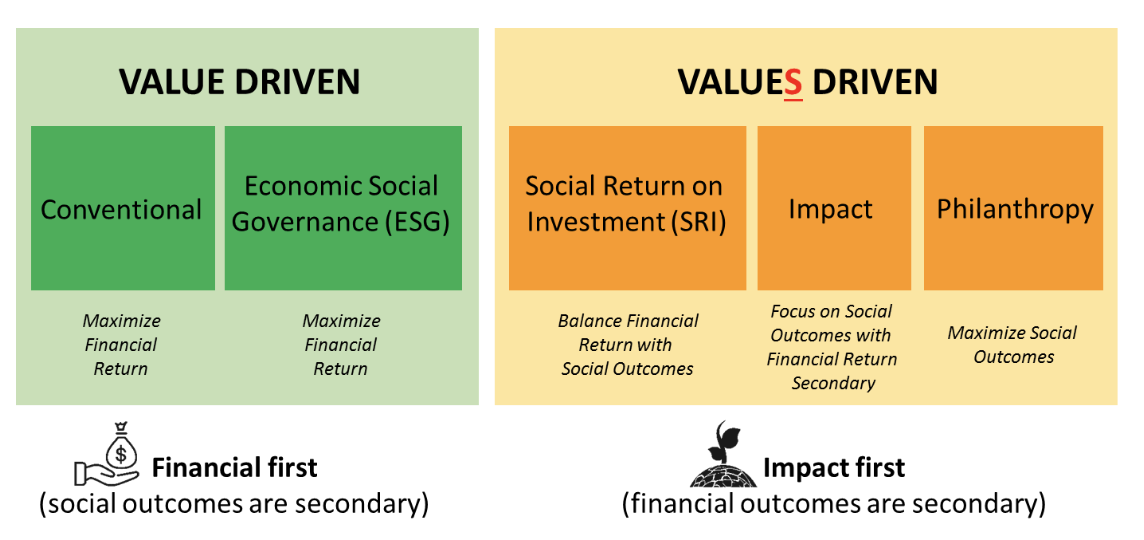

Similar as with Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability, the terminology surrounding sustainable investment can be quite ambiguous and has become a new “buzz” word. In many cases, it is rather detached from our earlier definition of Corporate Sustainability. To provide clarity on the topic, different frameworks have been proposed. The difference lies in what is seen as “sustainable” and whether the investor is mostly values-driven or profit-seeking (value-driven). A useful framework to identify the different investment strategies can be found below.

Value driven investing is about putting financial returns first. Conventional finance is concerned with maximising financial returns, but investors are increasingly recognising that considering Environmental Social Governance (ESG) risks is important for generating long-term financial returns.

Values driven, in comparison, sees generating a social impact at least equally important as generating a financial return. SRI focuses on balancing financial returns with social outcomes, but impact investing (in the figure above) is about focusing on social outcomes with financial returns as secondary, whilst Philanthropy is about maximising social outcomes only, without seeking any financial return.

Impact investing has seen exponential growth in demand around the world and in Australia, where Australia’s market has tripled in the last two years from $5.7 to $19.9 billion. A recent study also shows the growing appetite for impact investments is expected to grow more than 5 fold to $100billion over the next five years.

12.6.2.2 Sustainable Investing Tools

Common sustainable investment tools are:

- Negative screening: the exclusion of stocks based on social and/or environmental criteria. Many funds exclude, for example, firms deriving revenue from tobacco or selling firearms. It has also become common to exclude (divest from) fossil fuel companies.

- Positive screening: the selection of stocks based on positive social and/or environmental criteria. For example, a portfolio that invests in global environmental opportunities. This fund only select companies that meet certain environmental performance criteria.

- Shareholder Activism: Engagement of shareholders with companies on ESG factors. This tool is becoming increasingly common for shareholders, particularly in Europe.

Exercise

Multiple Choice

Recently 48.6% of shareholders backed a climate resolution that asked JP Morgan to describe its plans for aligning their financing with keeping global temperatures below 2 degrees (for more information, see Shareholders Urge JPMorgan Chase to Reduce Climate Impacts of Financing). What is this an example of?

12.6.2.3 Sustainable Investment Boosts

Given the (long-term) financial success of SRI/Sustainable investment funds, and demand from clients, many funds now offer sustainable/responsible investment options (see e.g. Morgan Stanley). However, how responsible/sustainable are these investments?

Recent research by Rekker et al. (2019) (yes, the lecturer of your course) found that sustainability ratings, often used by investors to make sustainable investment decisions, do not measure how consistently a company is operating with e.g. meeting global climate goals (so how can we create climate-safe investment portfolios?). The role of sustainability rating agencies is to analyse the company data and provide independent assessments on their sustainability. The landscape is quickly changing however. Over the past few years there have been major developments in the required disclosure and action of companies on climate change. For more information see the recommendations by the Task-Force on Climate-Related Disclosures, the Science-based Targets initiative, and the Transition Pathway Initiative.

12.6.3 Regulation of Sustainable Finance

The European Union (EU) has emerged as the predominant player in leading the way on the topic of sustainable finance. Given the lack of clarity surrounding “sustainability” and the mis-use of terms in the financial sector, the European Commission has adopted an action plan, leading the development of regulation on creating a sustainable financial sector. Its key actions include:

- Establishing a clear and detailed EU classification system – or taxonomy – for sustainable activities. This will create a common language for all actors in the financial system, and facilitates sustainable investments. The taxonomy is a 400 page document, including criteria for 70 climate change mitigation and 68 climate change adaptation activities, including criteria for do no significant harm to other environmental objectives. Companies and investors are expected to disclose sustainability information using the new taxonomy by the end of 2022.

- Establishing EU labels for green financial products. This will help investors to easily identify products that comply with green or low-carbon criteria.

- Introducing measures to clarify asset managers’ and institutional investor’s duties regarding sustainability. Traditionally, institutional investors (e.g. banks) only had a fiduciary duty to inform clients about their financial products, but this new regulation will clarify the duties surrounding disclosing sustainability aspects of their investments.

- Strengthening the transparency of companies on ESG policies.

- Incorporating climate risks into bank’s risk management policies and supporting financial institutions that contribute to fund sustainable projects.