4 Notating Time: Note Values and Rests

Introduction

As outlined elsewhere, the “time dimension” in Western music notation is represented on a horizontal axis. However, this is done in a way that is subtle, non-linear and bound by a number of customs.

For those completely unfamiliar with the Western system of notating music through time, some basic principles, terms and symbols are outlined in this chapter.

For the organisation and relationships of these materials, you are referred to chapters dealing with metre and rhythm.

Events and onsets

We will use the term “event” to describe any deliberate sound (or silence) that is part of a musical processes. Any sounding event will start at a point in time that we call an “onset.” It is useful to remember that:

- Events have a duration (think of them as a line)

- Onsets have no duration (think of them as a point)

One way to visualise this is to look at the wave form representation of an audio signal that we find in sound production software. Piano music is particularly good for this, because the piano’s sound produces a very well defined onset followed by a clear decay. An example is given below, from the opening moments of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto. In the excerpt, there are sixteen events of varying duration. The onset of each event is clear from the sudden increase in signal amplitude (vertical dimension) which then trails off as the sound decays. This is a very typical wave-form envelope for piano sounds. To make all of this absolutely clear, each event is highlighted yellow when you play the excerpt below.

Proportion

If you look at the second through to the twelfth event in the wave form above, you might detect that these have pretty much the same duration—they occupy the same amount of horizontal space. These correspond to the faster events that you hear in a series after the long one that starts the excerpt.

We can expand on all this by looking at a simplified, graphic representation of the wave form above. Here, the downward arrows point to the event onsets (which are numbered 1 to 16) and the red double-ended arrows show the duration between onsets (which, because there are no internal silences, is the same as the event durations).

As noted above, events 2 through to 12 all have the same duration. This duration is also the shortest of any event in this excerpt. For convenience, we will call this duration x. You will also notice that all the other durations can be expressed as whole-number multiples of x (2x, 4x and 5x). In other words, the values of all the durations have simple, proportional relationships.

Rhythm, metre and entrainment

Another thing that happens as you listen to the excerpt is that, after the initial event, whose length is unpredictable, the regularity and proportionality of the subsequent events quickly enables you to make sense of the time relationships described above. This is a basic cognitive capacity of humans called entrainment, or beat induction. Before half way through this excerpt, you can probably start to tap your foot to the underlying pulse, or beat. This pulse is represented by the circles in the top part of the graphic. The way in which these circles are initially greyed before becoming solid black is meant to symbolise the process of entrainment, which for most listeners would happen somewhere around where the squiggly line occurs.

The process of entrainment allows us to hear the music in this excerpt (and most music, for that matter) on two levels in the durational dimension. These are metre and rhythm. We will explore this in more detail later, but we can summarise the situation as follows:

- meter relates to the regular pulses or beats that we entrain to

- rhythm relates to the specific proportional relationships of the durations of musical events

Notating durations

Let’s return to the opening bars of the Beethoven Concerto we started with. Here is the musical notation (or score) of this excerpt. Note that elements in shades of blue have been added; everything in black is from the music Beethoven wrote down.

There is a lot of information to take in here, much of which we will return to at various points further down or in subsequent chapters. For the movement, concentrate on the arrangement of the note heads. On the great staff, the note heads are set out in two dimensions—vertical and horizontal. Groups of note heads that are stacked in the vertical (pitch) dimension sound simultaneously—the term used to describe such groups of notes is chord. The chords are then heard/played successively over time, moving from left to right on the horizontal dimension. The numbers in blue above the staff correspond to the numbered events we have already described. The light shaded triangles in the middle recall the original wave form. This should make clear the basic way in which the notation conveys the unfolding of music events.

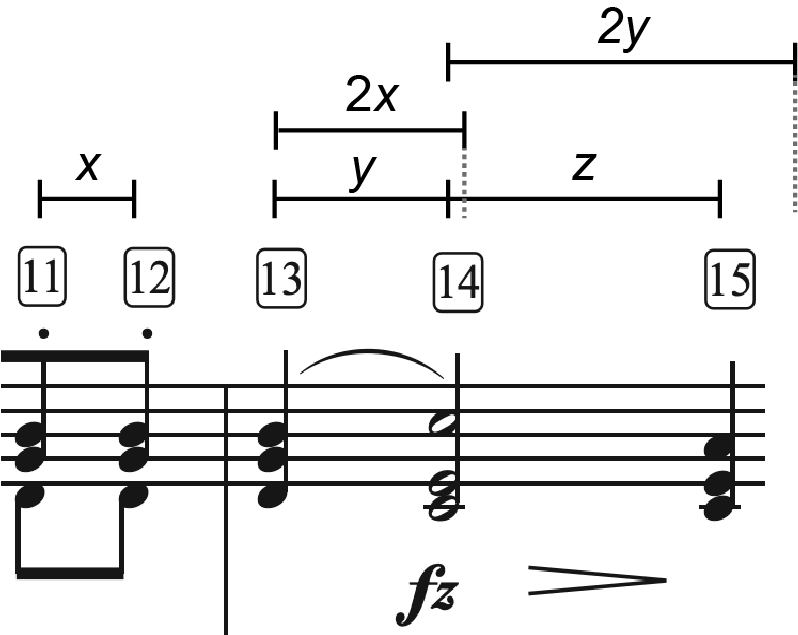

To add detail to this, the horizontal position and order of chords on the staff shows us order of the onsets of each chord (event). Also, it does carry some information about the duration of these events, but not in a precise way. For example, if you look at chords (events) 11, 12, 13 and 14 (right), you can see that, although we know already that 13 lasts twice as long as 11 or 12, the measurable distance, visually on the page, between 13 and 14 (shown as y on the right), is not literally twice that of 12 and 13, or 11 and 12 (x). Likewise, while 14 lasts twice as long as 13, the distance from 14 to 15 (z) is not literally twice that of 13 to 14 (y).

Time values, therefore, are not represented in strict proportion along the horizontal dimension of the staff. We need something else to provide precise information about duration.

Another thing you will notice is that while most of the note heads for these chords are closed, some are open (see those numbered 1, 14 and 16). Additionally, there are new elements attached to these note heads:

- vertical lines—called stems

- thicker, horizontal lines, joining some stems—called beams

- curved shapes attached to individual stems—called flags

The additional elements (open/closed note heads, stems, beams, flags) give us further information about duration of each note (event). Using these graphic elements in a variety of combinations allows us to show, symbolically, the proportional value of notes in relation to one another. As suggested above, the relationships of these durations are in a simple, arithmetical series—1:2:4:8:16:32 and so on. In other words, each duration can be changed by doubling or halving.

By convention we assign names to these values. In English there are two common naming systems in use, British and North American (US). This text follows the British naming conventions (which are standard in most Commonwealth countries), but the North American equivalents are also shown for reference as many texts refer to them. As you read down from the top of the chart below, you are halving durations. Conversely, you are doubling them as you read from bottom up.

Note that flags and beam represent the same thing in terms of relative value. Beams are used to visually groups notes of the quaver value and smaller in a way that makes musical rhythm easier to read. There are a complex set of rules and conventions around this which is explained gradually in other parts of this text.

Last, but far from least, music also involves the use of silence. A silence in music is called a rest, and rests also have specific symbols. We call them by the same name as the note durations, but add the word “rest”—e.g. a “quaver rest,” a “minim rest,” and so on. Their signs are shown in the second column.

Another way of looking at these relationships is shown below, starting at the level of the semibreve. To some extent, this explains the logic of the US naming conventions in the sense that they all can be related as fractions to the longest value—e.g. there are sixteen semiquavers to a whole-note (hence, “sixteenth notes”). However, the value of this consistency is only relevant to one type of time (simple quadruple) and can become confusing in other contexts, and the terms turn out to be as arbitrary in their own way as the British ones.

Ties and dots

There are two other important notational symbols that affect the duration of notes: ties and dots.

A tie is a curved line that connects two or more note values of the same pitch, showing that only the first note creates an onset, but that the duration following that onset is equal to the sum of all values. Ties are always placed adjacent to note heads, as shown in the examples below. Mostly, the curve of the tie goes in the opposite direction to the stems.

If a note head has a dot added immediately to its right, this indicates a lengthening of the note by exactly one half. We can use more than one dot to indicate a further addicting of half the value added by the previous dot. Rests can also be lengthened by half their value by adding a dot.

The exact placement of the dot depends on whether the note head rests on a line or space. If the note head is in a space, the dot is level with the centre of the note head, if the note head sits on a line, then the dot is offset to the middle of the space above.

A point of confusion with dots can arise between augmentation dots (which show additional time) and staccato signs (which indicate an articulation effect requiring adjacent notes to be separated by a short break). Staccato signs are always placed directly above or below a note head, not after it.

Augmentation dots add exactly half the value of the note and thus delay the onset of the next event by that amount

Staccato signs shorten the length of a note, but do not affect the onset of the next note. The effect is to add a rest to fill the full value of the note but not change the time between onsets. The amount of rest is not precise but, rather, dependent on style and taste.

If we go back to our opening excerpt (Beethoven Fourth Piano Concerto) we now have some terminology to make some sense of the organisation of time in the piece.

There are three different values used—minims, crotchets and quavers.

The opening chord lasts exactly five quavers in value, because its minim is tied to a quaver.

There are no augmentation dots used, although some chords have staccato signs.

There are some other time-related elements to consider before leaving this excerpt. These are (as marked on the score):

- Time signature

- Bar lines and bars

- Tempo indication

The time signature gives us information about the metre, the underlying pulse and a hierarchy of beats that we sense under the surface of the rhythm. In this example, the symbol that looks like a large “C” on each part of the grand staff is a common-place abbreviation that tells us that the underlying beat is measured in crotchets and that there is a hierarchy of beats whereby the first beat of every group of four is emphasised.

The bar lines provide a visual marker that contains each group of beats (in this case, four). An entire span of music from one bar line to the next is called a bar (or “measure,” in North American terminology)

Unlike the first two elements above, the tempo indication is a subjective element—tempo means speed or pace. The tempo indication here is descriptive. “Allegro” means fast; “moderato” means moderately. So the indication is “moderately fast.” Exactly how fast “moderately” fast is will depend on a range of subjective factors—conventions, individual taste and artistic choice, and so on.

Sometimes, a more precise indication of tempo can be given by assigning a metronome mark. For example, the excerpt above might play at around ![]() . This means a rate of 112 crotchets per minute, or just a bit less than two every second. 𝅘𝅥

. This means a rate of 112 crotchets per minute, or just a bit less than two every second. 𝅘𝅥

Metre (meter) in music refers to the organisation of regular pulses into recurring groups, mostly in relations of two or three.

Rhythm in music is understood as the configuration of musical events in time. A musical rhythm is, essentially, a set of (usually simple) specific time relationships heard against the backdrop of a regular metre.

A score is the written representation of a piece of music.

A chord is any simultaneous combination of musical notes. Within chords as a class, there are also more specific kinds of chords with specific names, such as "dyad" (any two-note chord), "triad" (a three-note chord with notes related by the interval of a third), and so on.

A rest is a specified duration of silence in music, or the symbol indicating that an instrumental or vocal part is not to play or sign for the specified duration.