3 Notating Pitch: Staff Notation

Introduction

Staff notation is the system by which pitch is represented in Western music. It has evolved over several centuries into the form in common-use today, which has remained largely unchanged since the seventeenth century. It comprises several distinct elements which work together to indicate the precise pitch of notes: the staff itself, various clefs, note heads, leger lines, and accidentals.

The staff

The staff consists of five horizontal lines, and four spaces (Example 00). Both the lines and the spaces are used to indicate the pitch of a note. The higher the line or space, the higher the note.

Example 00: The five-line staff

To indicate a note of a certain pitch, we place a note head (which can be “closed”: or “open”:

) on a line or a space. We can also place note heads immediate above or below the staff. If we still need to go higher or lower, we can add leger lines that temporarily extend the staff and show the position of each note head precisely above or below the standard five-line staff. Leger lines are always spaced the same distance above or below the staff as the staff lines themselves. Example 00 shows some cases of placing notes on and above or below the staff using leger lines.

Example 00: Placement of note heads on the staff

The staff tells us the relative position of notes (higher or lower). In order to let it tell us precisely what notes are shown, we require an additional piece of information. This comes in the form of a clef.[1]

Clefs

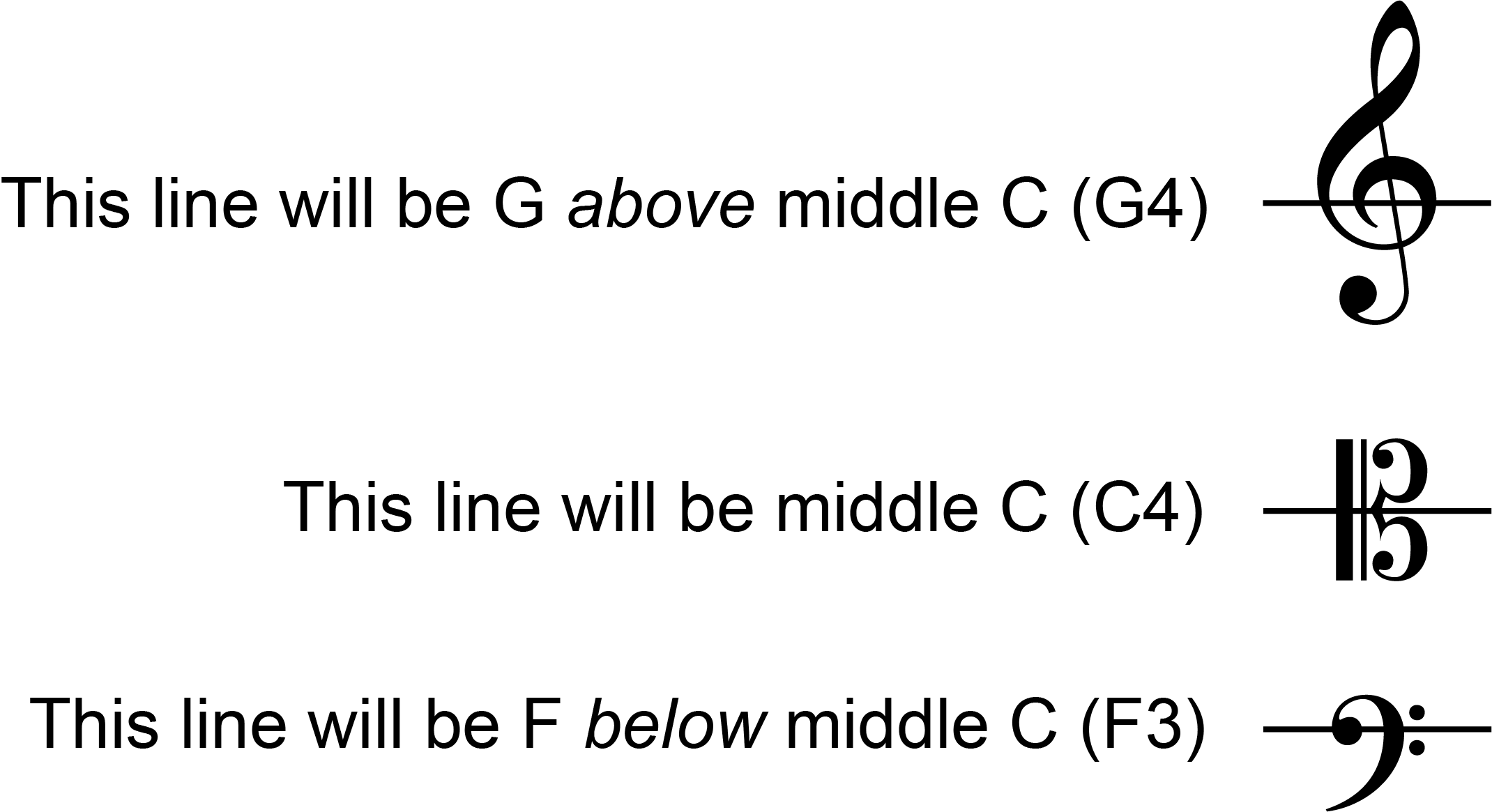

A clef is a symbol which shows which lines and spaces of the staff represent specific notes. There are three different clefs in common use today, the G clef, the C clef and the F clef (Example 00).

Example 00: The three standard clefs

Each clef fixes a line of the stave to a particular pitch, thereby also showing all the other associated pitches by relation.

- The lower part of the G clef curls around a line, identifying it as G above middle C (G4)

- The C clef centres around a line, identifying it as middle C (C4)

- The F clef, with its two distinct dots, identifies a line as F below middle C (F3)

Example 00: How the three standard clefs identify the pitch of a line of the staff

It is possible to place any of these clefs on any line of a staff in order to determine the relative pitch of all the others lines and spaces. However, in contemporary practice, most music uses one position for the G and F clef, and two positions of the C clef.

- The G clef is mostly placed on the second line of the staff, and in this position it is also called the “treble” clef

- The C clef is mostly placed on the third of fourth line of the staff, and in this position it is also called the “alto” or “tenor” clef, respectively

- The F clef is mostly placed on the fourth line of the staff, and in this position it is also called the “bass” clef.

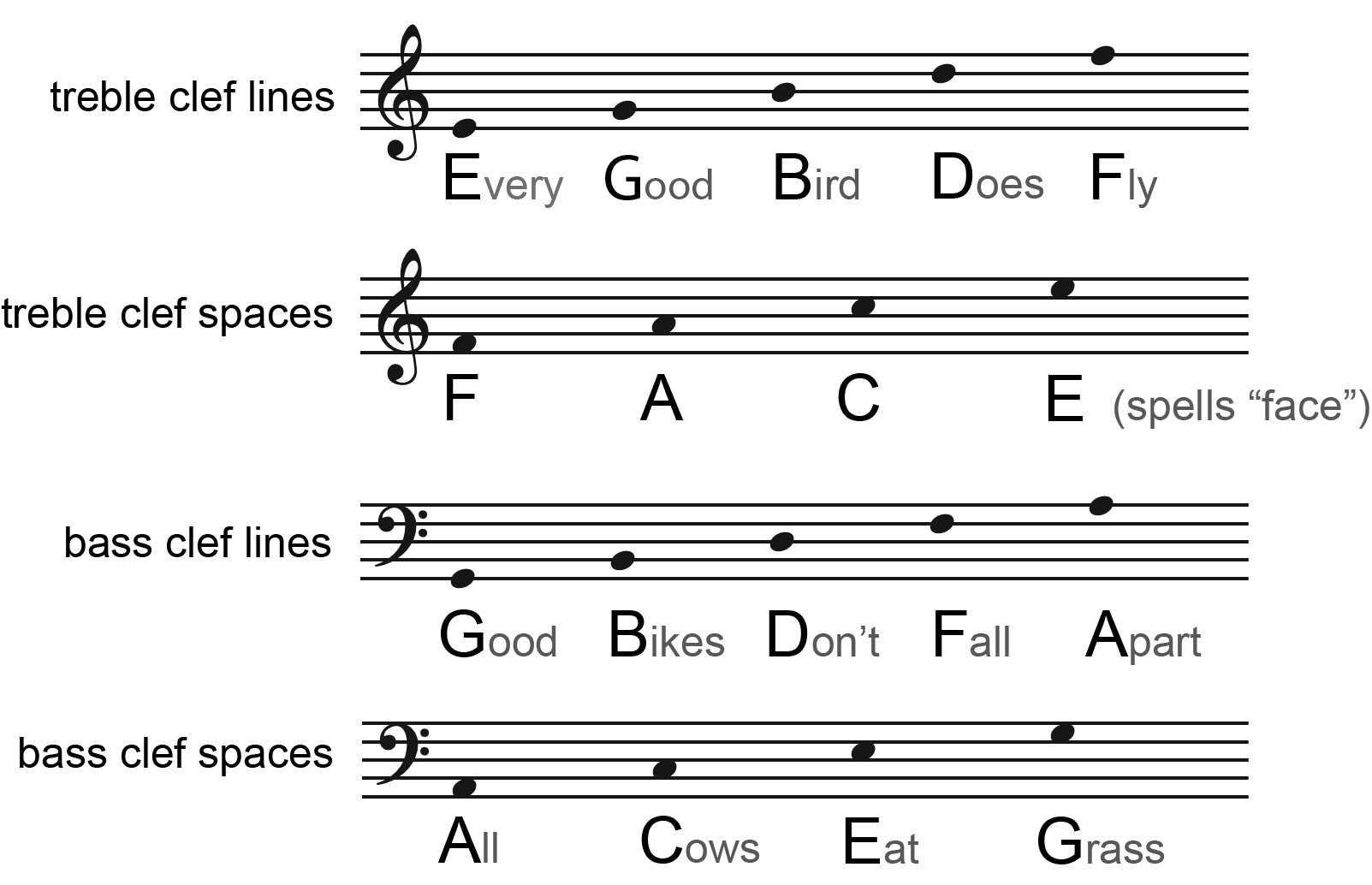

The Treble and bass staves

A staff with the treble clef is usually called the “treble staff,” and one with the bass clef, the “bass staff.” Between them, the treble and bass staves are able to represent a large range of notes, from F2 to G5, and even more when we employ leger lines.

When first reading from a staff, it is easy to forget which lines and spaces are attached to which notes. A popular way to remember is to use mnemonics for the lines and spaces for each staff. Below are some common ones for the treble and bass staves. There are other ones, and ones for other staves, and you can also make up your own, if that helps.

Example 00: Common mnemonics for the lines and spaces on the treble and bass staves

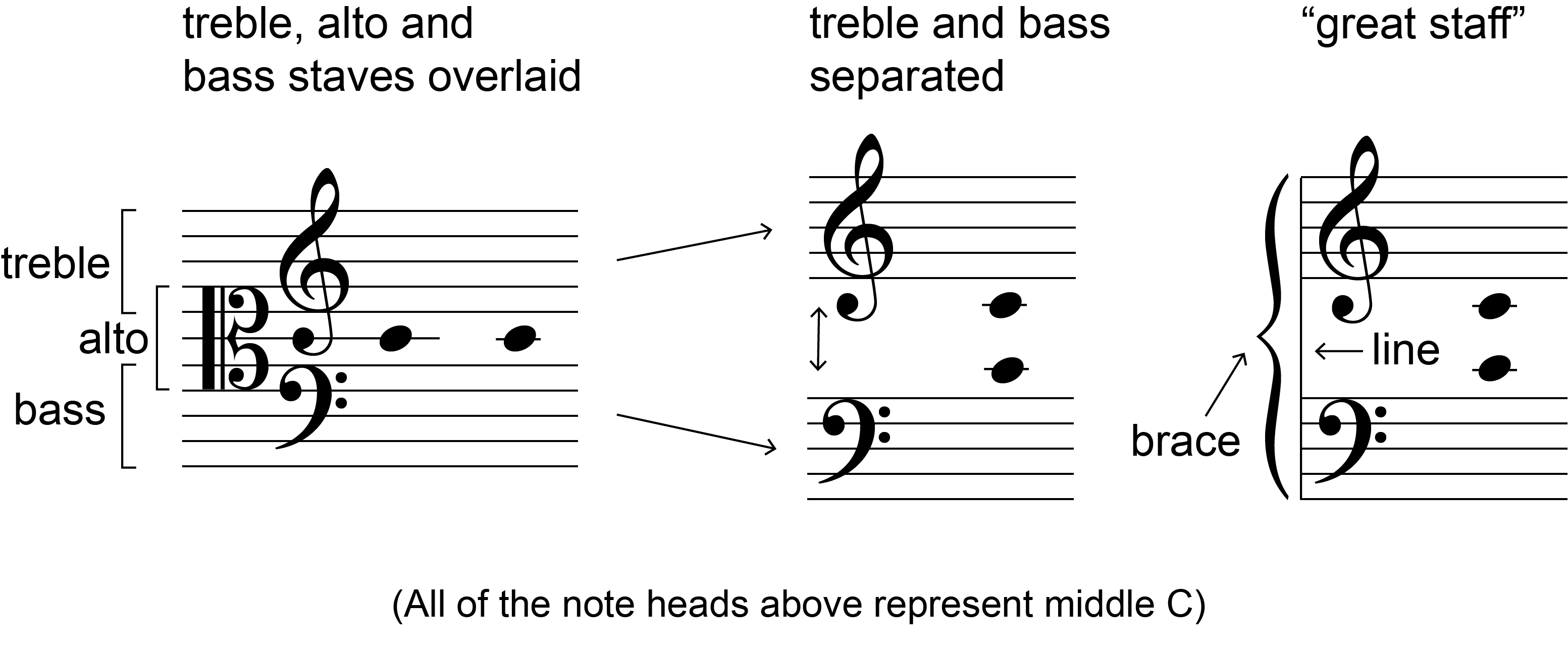

The great stave

If we look closely at the treble and bass clefs, there is a kind of symmetry around middle C, in the sense that middle C sits on the first leger line below the treble clef and the first leger line above the bass clef. Now imagine an overlay of the treble, alto and bass clefs, so that the upper two lines (E and G) of the alto clef are also the bottom two lines (E and G) of the treble clef, and the bottom two lines of the alto clef (F and A) are the upper two lines of the bass clef (F and A), the result would be a kind of eleven line “super” staff, as show on the left in Example 00. If we then removed the alto clef’s middle line (middle C) we could also imagine middle C as a note head on a leger line that is a remnant of this alto clef.

Example 00: Derivation of great staff

Now, if we separate the treble and bass clefs vertically, as shown in the middle part of Example 00, then middle C must be represented now separately on each clef, with its own leger line.

Finally, we can show a connection between these two now separated staves by joining then with a line and a brace (as shown on the right). This is known as the great staff.

The great staff is used extensively in Western music. Its common uses include:

- Notations of most keyboard music[2]

- Reductions to two staves of four-part vocal music

- Reductions of other instrumental ensembles to a condensed format for playing at the piano or study

- Presenting examples of music for analytical or theoretical discussions

With the use of up to three leger lines, we can show the range of (white) notes from G1 to F6. Note also, that there is often some overlap and flexibility between the two staves (treble and bass) that comprise the great staff. It is not uncommon to write notes at least two, and often more, leger lines below middle C on the treble staff and above middle C on the bass staff, depending on the context.

The piano keyboard—”black” notes

Returning to the piano keyboard, we can consider the notes of the Western notation system that we have not yet covered—those identified with the piano’s “black” keys. In the picture below, we can see the inside of an upright piano, showing the action that links the hammers in a row along the upper part of the picture) to the keys. Each hammer strikes a set of similarly tuned strings (usually three).

Note that each hammer links to an adjacent key, black or white. So only the white keys that are not separated by an interleaved black key strike a set of strings that are directly adjacent. White keys that are separated by a black key strike a set of strings that are separated by one set. Each adjacent set of strings is tuned to notes that are heard to be the same interval apart. Therefore, for the various adjacent pairs of white keys, there are two different possible intervals, one smaller than the other:

- smaller (no intervening black key): B to C and E to F

- larger (one intervening black key): C to D, D to E, F to G, G to A, A to B

The smaller interval is called a semitone and the larger interval is called a tone (or sometimes a whole tone in order to distinguish it from a semitone).[3]

Tones and semitones, sharps and flats

A semitone is the smallest standard interval in the Western music system. It is the interval that separates two directly adjacent notes on the piano keyboard, black or white. In Example 00, we can see at the bottom the pattern of tones and semitones that separate the white-key notes A to G. We also see, along the top, how every key, black or white, sits a semitone higher or lower than its adjacent neighbour. Adjacent black keys within a group sit a tone apart, and at the end of a group of black keys, skipping the immediately adjacent white key to the next, also is a tone.

Example 00: Tones and semitones on the piano keyboard with note names and accidentals

We are now able to give names to the notes sounded by the black keys. These are defined as “sharp” or “flat” versions of the white-key notes.

- To “sharpen” in music means to raise the pitch of a note

- To “flatten” means to lower the pitch of a note.

When we add the terms “sharp” or “flat” to a note name, such as A, it means that we are raising or lowering the pitch by a semitone. On a piano:

- to play “A sharp” means to play the black key immediately to the right of A;

- to play “A flat” means to play the black key immediately to the left of A

This means that the black-key notes all have two names. For instance, “D sharp,” the black key immediately to the right of D is the same black key immediately to the left of E, meaning it can also be called “E flat.” This is known as enharmonic equivalence.

In fact some of the white-key notes also have enharmonic names—for instance, B can also be named C flat, F can be called E sharp, and so on.

Music has five symbols which denote the various alterations possible to notes. These signs are known as accidentals. The name is somewhat misleading, as there is nothing really “accidental” about them. They are as follows:

The last two will not concern us quite as much immediately, but it is advisable to get to know them.

Writing notes with accidentals

When we write attach these symbols in writing, we add them after the letter name. For instance, A flat is written A![]() , C sharp is written C

, C sharp is written C![]() , and so on. However, in music notation, the accidental sign is always placed directly in front of the note head it modifies. Additionally, there are some other rules to follow:

, and so on. However, in music notation, the accidental sign is always placed directly in front of the note head it modifies. Additionally, there are some other rules to follow:

- Always place the accidental close to the note it modifies, but leave a small gap

- Always place the accidental on the same line or space of the note it modifies.

- Make sure the accidental is neither too large, nor too small for reading: sharp and natural signs are about three spaces high; flat and double flat signs are about two spaces in size; the double sharp sign is a space in size.

Below are examples of good and poor notation practices for placing accidentals.

- The word clef comes from the French word for key—it should not be confused with the concept of a musical key (such as the key of C major, etc.). ↵

- Organ music may have three staves, with the lowest for the pedal board ↵

- In some texts you will find that semitones are referred to as half steps and tones are referred to as whole steps. ↵

A brace is the curly bracket on the left that joins individual staves to form (mostly) the great staff. Braces can be used to join other groups of staff in various score formats.

Interval refers to the quantitative (and sometimes qualitative) distance between to notes, measured by successive adjacent notes.

A semitone (also called a half step) is the smallest interval in the Western twelve-tone tempered system, also defined by two directly adjacent notes on a piano keyboard (black or white).

A tone (also called a whole step) is the next largest interval, after the semitone, in the Western twelve-tone tempered system. It is equal to two semitones.

Enharmonic equivalence refers to the assigning of different note names to the same pitch.

A accidental is a sign prefixed to a note head which alters the designated pitch by raising or lowering it, or restoring it to its unaltered state. A sharp (♯) raises pitch by a semitone, a flat (♭) lowers pitch by a semitone, a natural (♮) restores a note to its "white-key" pitch, a double sharp (𝄪) raises pitch by a tone (two semitones) and a double flat (𝄫) lowers pitch by a tone (two semitones).