3 An Introduction to Neurobiology for Counsellors

Kate Witteveen

“A healthy mind is a mind that creates integration within the body and its brain, and within relationships with other people and the planet” (Siegel, 2019, p. 229).

Key Takeaways

- An understanding of the brain, the nervous system, and the mind are foundational to the work of the counsellor.

- This understanding extends beyond the structure of the brain and nervous system, to how the various parts of the body and mind individually and collectively contribute to human experiences through the processing and interpretation of sensory information.

- Scientific advances are constantly updating our knowledge and understanding of the brain, so it is imperative that counsellors continue to engage with current literature.

- Integration within the individual, and between the individual and others, is a key indicator and facilitator of mental health and wellbeing.

Introduction

As counsellors, it is essential to have a working knowledge of brain and nervous system structure and function, because these have implications for all facets of our work with clients. As technological and scientific advances provide more clarity about the ways in which neurobiology intersects with all aspects of the human experience, it is crucial that we, as professionals, continue to remain informed about how an understanding of neurobiology can inform and enhance our professional practice (Gilbert, 2019).

When thinking about the brain and nervous system and their respective processes, it is reasonable to assume that the structures of the brain and the functions they perform are relatively well understood. To some extent, this is correct, and we will be exploring precisely these structures and functions later in this chapter. However, it is also correct to note that our understanding of the ways in which these structures and functions are interconnected with one another, and with the individual’s outer world, is continuously expanding (Poeppel & Idsardi, 2022; Siegel, 2020).

This expansion of knowledge is contributing to not only understanding what is happening within the individual, but also what is happening between separate individuals when they are in communication with one another. As counsellors, it is this interconnectedness of the inner and outer experience that is foundational to our practice, and thus, ensuring we have a foundational knowledge of neurobiology is crucial to our capacity to continue to develop our ability to provide effective support to our clients (Hertenstein et al., 2021).

Our understanding of neurobiology and its influence on counselling necessarily begins with a consideration of the basic structure of the brain and nervous system. In the next section, we will learn about the macro-structure of the brain and the functions associated with each structure. We will do this, however, keeping in mind that none of these structures are solely responsible for any given function, and there is increasing evidence to suggest that it is the connections between structures (Smith et al., 2015), and the integration of the inner and outer environments that are the greatest contributors to our experiences (Siegel, 2020), as opposed to the structure or function of any individual area of the brain. We will begin our exploration of neuroanatomy with an introduction to the nervous system.

Theoretical/Conceptual Foundations

The Nervous System at a Glance

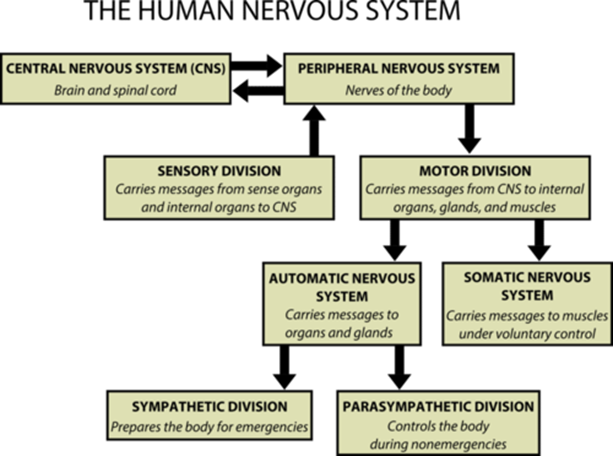

The nervous system is comprised of several complementary yet distinct subsystems which, together, are responsible for the functioning of the body. A detailed account of the nervous system is beyond the scope of this chapter, but we will consider a brief overview of the basic structure and function of the nervous system, as a foundation for understanding how it is implicated in the counselling process. If you are interested in a more thorough explanation of the nervous system, you may like to consult Bazira (2021).

At a macro level of organisation, the nervous system is comprised of two subsystems, namely the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Together, the brain and the spinal cord form the CNS, while the PNS is comprised of all of the other nerves within the body. The PNS serves as the connection between the CNS, the rest of the body and the external environment, and is responsible for sensory and motor functioning. Within the PNS, the somatic nervous system controls voluntary movements, and the autonomic nervous system is responsible for involuntary functions. (Waxenbaul et al., 2023)

The two subsystems within the autonomic nervous system include the sympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for responding to stimuli that could represent a threat (the fight, flight, freeze or fawn response) (Sherin & Nemeroff, 2011), and its complementary subsystem, the parasympathetic nervous system which returns the body to homeostasis when the threat has passed (the so-called rest and digest function) (Waxenbaul et al., 2023). The structure of the nervous system is depicted in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The Human Nervous System

We will revisit the nervous system later in this chapter when we learn about Polyvagal Theory (Porges, 2022; Porges et al., 1994) and Interpersonal Neurobiology (Siegel, 2020) as frameworks that are helpful for understanding the implications of neurobiology for mental wellbeing generally, and counselling more specifically. For now, you are encouraged to spend a few moments familiarising yourself with the overall structure and general functioning of the nervous system, as this is foundational to the remainder of this chapter.

Macro-anatomy of the Brain: Brain Stem, Cerebellum, Cerebrum and Cerebral Cortex

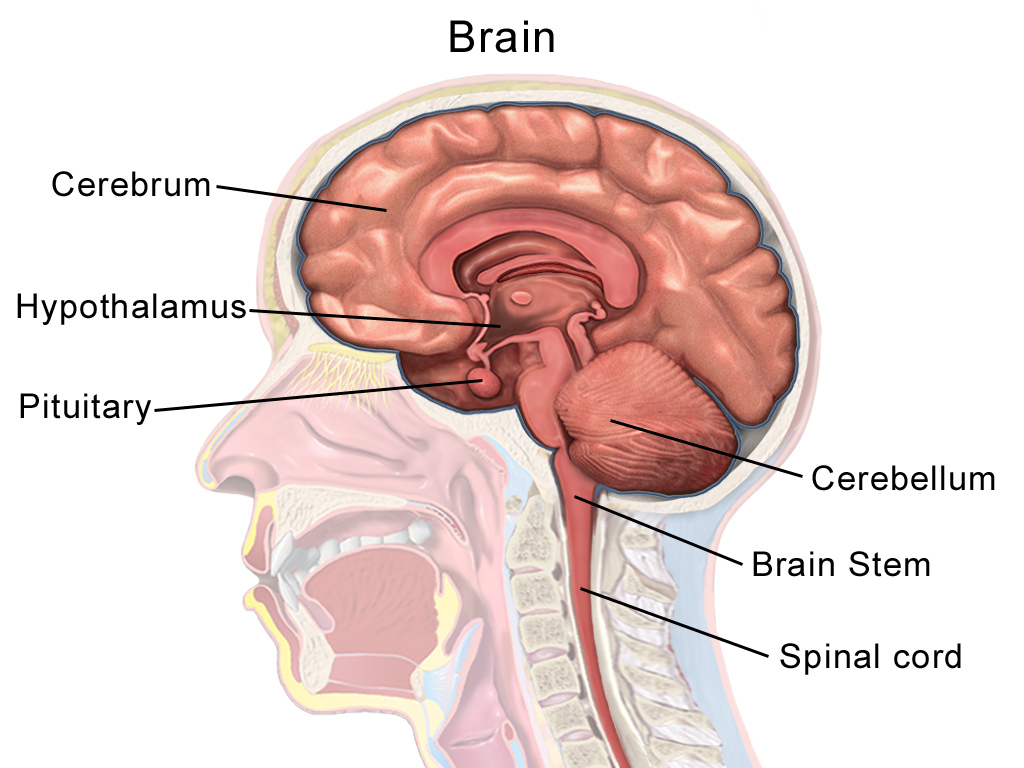

The brain stem, which is located at the base of the skull and connects to the top of the spine, is responsible for the basic functions associated with being alive, namely breathing and heart rate (Maldonado & Alsayouri, 2023). The cerebellum is located just above the brain stem and is implicated in coordinating movement, balance, vision, and the acquisition of motor skills (Jimsheleishvili & Dididze, 2023).

The cerebrum is the largest part of the brain, and is responsible for many functions, including conscious thought, processing sensory input, language, memory, movement, learning and emotions (Bui & Das, 2023). The cerebrum is divided into the left and right hemispheres and contains the lobes of the brain. The outer layer of the cerebrum is the cerebral cortex, which consists of folds (sulci) and raised areas (gyri) which give it a wrinkled appearance (Maldonado & Alsayouri, 2023). The brain stem, cerebellum, cerebrum, and cerebral cortex are depicted in Figure 2 below. Although not labelled, the cerebral cortex is depicted as the surface area of the cerebrum.

Figure 2. Brain Anatomy

Left and Right Hemispheres and Hemispheric Lateralisation

As previously identified, the cerebrum is comprised of two hemispheres (left and right) which are connected to one another by the corpus callosum. Integral to our understanding of the brain is the concept of hemispheric lateralisation, which relates to the recognition that each hemisphere is implicated in different ways of processing information (Rogers, 2021). Historically, it was believed that brain asymmetry and lateralisation were unique to humans, but it is now understood to occur in other species and to have identifiable evolutionary benefits (Güntürkün et al., 2020), including more efficient and effective cognitive processing capacity (Rogers, 2021).

Although there are multiple approaches to conceptualising, identifying, and explaining the ways in which the hemispheric lateralisation of the brain informs information processing, there is general agreement that the left hemisphere is associated with skills such as language, logic and mathematical functions, and the right hemisphere is associated with visuospatial and creative functions (McHenry et al., 2013). However, it has been suggested that this delineation of hemispheric functions is overly simplistic (Ross, 2021), and that it may be useful to conceptualise the different functions as relating to specificity and focus (left hemisphere) and breadth and flexibility (right hemisphere) (McGilchrist, 2010).

For our purposes, it is helpful to recognise that the two hemispheres appear to engage in distinct yet complementary information processing approaches that are communicated cross-laterally by the corpus callosum (McHenry et al., 2013). This cross-lateral communication has been identified as an important mediator of mental health outcomes (Siegel, 2019), and the corpus callosum appears to be highly vulnerable to adverse events, particularly during early developmental periods (Teicher et al., 2004). Taken together, these findings suggest that, irrespective of the specific hemispheric lateralisation of functions, cross-lateral communication is critical to mental health, and the size and functioning of the corpus callosum is crucial to all aspects of information and emotional processing (Siegel & Drulis, 2023).

Lobes of the Brain

In addition to being divided into the left and right hemispheres, the cerebrum is further divided into four lobes, namely the occipital, parietal, temporal and frontal lobes. Each lobe has a left and right structure, contained within the two hemispheres (Maldonado & Alsayouri, 2023). The occipital lobes are located at the back of the skull, just above the brain stem. The occipital lobes contain the primary and secondary visual cortices and are involved in visual processes (Rehman & Al Khalili, 2023). Brain imaging has also shown that the occipital lobes are active during dreaming (McHenry et al., 2013).

The temporal lobes are located at the sides of the skull. Both the left and right temporal lobes are implicated in learning, with the left temporal lobe emphasising verbal learning and the acquisition of language, and the right temporal lobe more involved in learning non-verbal information and interpreting facial expressions (Patel et al., 2023). There are several structures within the temporal lobes that are implicated in cognitive and emotional processing and are thus particularly relevant for counsellors.

For example, the hippocampus is important in the creation of declarative memories, and the amygdala is involved in various key functions including the processing of emotionally laden stimuli (including fear, aggression, reward processing and motivation) (Patel et al., 2023). While acknowledging that the functions of the hippocampus and the amygdala are highly sophisticated and nuanced, if we accept the basic premise that the hippocampus is involved in memory and the amygdala is involved in emotion, it is unsurprising to learn that these two parts of the brain are implicated in a range of psychiatric diagnoses, including addiction and post-traumatic stress disorder (Patel et al., 2023).

The parietal lobes are located above the temporal lobes and behind the frontal lobe. These areas are involved in the perception and integration of sensory information and generating responses to stimuli (Dziedzic et al., 2021). The parietal lobe is responsible for assessing where you are in relation to other objects (proprioception), as well as perceiving temperature, pressure, vibration, and pain (Jawabri & Sharma, 2023).

Finally, the frontal lobes are located at the front of the skull. As the most recently evolved part of the brain, the frontal lobes are responsible for higher order cognitive functioning, such as reasoning, logic, problem-solving, decision making, attention, intelligence, motor functions and other voluntary behaviours (Collins & Koechlin, 2012). Firat (2019) proposed a hierarchical model to describe the ways in which the frontal lobe influences human behaviour and social connectedness. The levels within that hierarchical model include:

(a) Voluntary, controlled behaviour including motor functions;

(b) Motivation and emotional regulation; and

(c) Higher-order executive functioning.

The location of each of the lobes of the brain can be seen in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Lobes of the Brain

The Limbic System

The limbic system is a group of structures that collectively regulate behaviour, emotions, memories. The limbic system recognises threats and activates the autonomic nervous system to respond to those threats. As described by Kaushal et al. (2024), the main structures and functions of the limbic system are:

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus links the nervous system and the endocrine system and is involved in maintaining homeostasis. Like a thermostat, the hypothalamus regulates the body’s functioning such as body temperature, blood pressure, hunger and thirst, mood and sleep. The hypothalamus functions by creating hormones or signalling to the pituitary gland that hormones need to be released. It is part of the stress response system known as the HPA-axis, which we will discuss in a moment.

Thalamus

The thalamus processes sensory information (with the exception of smell) and contributes to memory, planning and emotions. The thalamus can be likened to a postal service sorting centre, where the information packages are received (in the form of sensory inputs) and distributed to the relevant address/location in the brain for action. The thalamus is involved in relaying sensory and motor information, prioritising attention, the awake/sleep cycle, thinking and memory.

Amygdala

The amygdala is involved in various key functions including the processing of emotionally laden stimuli (including fear, aggression, reward processing and motivation). The amygdala plays an important role in detecting danger and is essential to survival. Among other functions, the amygdala contributes to the connection of memories and emotions.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is important in the creation of short-term and long-term declarative, visual-spatial and verbal memories, and is foundational to the ability to learn. The hippocampus works with the amygdala in the connection of emotions to memories.

When we consider that the hippocampus is involved in memory and the amygdala is involved in emotion, it is unsurprising to learn that these two parts of the brain are implicated in a range of psychiatric diagnoses, including addiction (Fang et al., 2022) and post-traumatic stress disorder (Kamiya & Abe, 2020).

Pituitary Gland

Known as the “master gland”, the pituitary gland is responsible for the creation of a number of different hormones including adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) which tells the adrenal gland to make hormones. This process occurs when threats are detected, and forms part of the HPA-axis.

The HPA-Axis

The HPA-axis is comprised of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland and the adrenal glands. When a threat is detected by the autonomic nervous system, the hypothalamus releases corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH). This is the signal for the pituitary gland to release ACTH which, in turn, signals to the adrenal glands to release cortisol (the stress hormone) (Herman et al., 2016).

In a typically functioning nervous system, the release of cortisol serves as a negative feedback loop, signalling to the hypothalamus to stop the production of CRH, and allowing the parasympathetic nervous system to restore homeostasis. In individuals who have experienced prolonged stress or adversity, this negative feedback loop may become impaired, and the sympathetic nervous system response continues unnecessarily (Juruena et al., 2021). HPA axis dysfunction can have significant health consequences, including immune system dysfunction and inflammation, as well as mental health conditions such as mood disorders and PTSD (Haahr-Pedersen et al., 2020).

This consideration of the anatomy of the brain has been intentionally brief and simplified. The purpose of this section was to introduce you to the macro-anatomy of the brain, together with some of the general functions associated with the various regions of the brain. If you are interested in learning more about how neuroanatomy and neuroscience inform counselling, you may find the text by Wilson (2014) of interest.

Helpful hint. An easy way to remember the location and function of the parts of the brain is to consider the evolutionary development of the brain. As a general principle, the more primitive structures associated with basic functioning are located at the back of the skull, and the more evolved structures that are associated with higher-order functions are located at the front.

The Brain: Other Key Characteristics that are Foundational to Therapy

Many historical theories of human development emphasised the growth and development of the brain across childhood and adolescence, with less consideration given to changes that may occur in adulthood (Babakr et al., 2019). However, understandings of brain development across the lifespan have changed dramatically, as innovative technologies have expanded and enhanced the ways in which we can measure brain structures and monitor brain activity (Mateos-Aparicio & Rodriguez-Moreno, 2019).

A pivotal finding that has influenced all disciplines interested in the study of the brain, is the ability of the brain to adapt and change, known as neuroplasticity (Fuchs & Flügge, 2014). Of particular importance were early imaging studies which identified patterns of neuronal death associated with illnesses such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, but also the growth of new neuronal pathways, known as neurogenesis (Kuhn et al., 2001).

In the early 2000s, studies began to emerge which suggested that, rather than being complete by the conclusion of adolescence, the brain continued to grow and develop in young adulthood, culminating in a ‘mostly’ fully developed brain, as operationalised by the development of the prefrontal cortex, by the age of 25 (see, for example, Arain et al., 2013; Tierney & Nelson, 2009).

However, recent data have emerged that suggests the brain continues to change across the lifespan, to a much greater extent than previously believed (Bethlehem et al., 2022). For example, a seminal study conducted by Bethlehem et al. (2022) examined an aggregated sample of 123,984 MRI scans from 101,457 participants, ranging in age from 115 days post-conception to 100 years of age. This extensive data set indicated that, although there was less evidence of neuroplasticity in older adults compared to younger adults, the brain continued to exhibit neuroplasticity across the lifespan.

When considering the location and type of neuroplasticity observed in older adults, it was proposed that the apparent reduction in neuroplasticity across middle and older adulthood could be a product of neuroplasticity becoming more strategic, rather than a diminished ability of the brain to adapt (Bethlehem et al., 2022). These findings are very recent, and this is a rapidly expanding body of knowledge, which will undoubtedly continue to evolve in the coming years.

For our purposes, the key implication of this section is that the brain continues to be impacted by the individual’s environment and life circumstances across the lifespan (Glasper & Neigh, 2019) and neuroplasticity and neurogenesis do not cease at the age of 25 (Bethlehem et al., 2022). These characteristics of the brain are foundational to the work of therapy (McHenry et al., 2013), as they inform our conceptualisation and understanding of our clients’ situations, as well as the opportunities for meaningful intervention.

Although there are identifiable periods of sensitivity that may render individuals more vulnerable to negative impacts of adverse circumstances (Siegel, 2019), there are measurable changes in the structure and functioning of the brain that can occur as a result of a range of experiences and circumstances right across the lifespan (Akil & Nestler, 2023; Gonda et al., 2022; Thumfart et al., 2022). As such, adverse experiences do not simply result in subjective feelings of distress and, equally, therapy does not simply help individuals to subjectively feel less distressed. Rather, both the adverse events and the therapeutic interventions have the capacity to alter the individual’s neurobiology (see, for example, Petrocchi & Cheli, 2019). Some potential mechanisms for this impact are proposed by two theories we will consider in the next section, namely Polyvagal Theory (Porges et al., 1994; Porges, 2022) and Interpersonal Neurobiology (Siegel, 2020).

A Framework for Understanding the Connection Between Neurobiology and Counselling

A substantial body of literature has established relationships between adverse experiences and measurable changes in the structure and functioning of the brain (Hosseini-Kamkar et al., 2023). These findings provide evidence of the effect of the external environment on an individual’s neurobiology. Further, there is also evidence to suggest that an individual’s neurobiology has quantifiable impact on their external environments, including their relationships with others (Siegel & Drulis, 2023).

A number of theories have been developed to account for these bidirectional relationships. In this section, we will examine two influential theories that provide complementary frameworks for explaining the mechanisms by which an individual’s inner and outer experiences are mutually influencing. These theories are Polyvagal Theory as proposed by Porges (1994) and Interpersonal Neurobiology as proposed by Siegel (2020).

Helpful hint. You may recall that earlier in this chapter, we considered an overview of the nervous system. That overview of the nervous system is foundational to the following sections, so you may like to refresh your memory about the structure and function of the nervous system before proceeding to the next section.

Key Principles

So far in this chapter, we have explored the macro-structure of the brain and its associated functions. We will now briefly consider two major theories that describe the mechanisms by which our nervous systems influence our experiences and interactions with others, namely Polyvagal Theory and Interpersonal Neurobiology.

Polyvagal Theory and Interpersonal Neurobiology share an emphasis on explicit and measurable relationships between neurobiological functioning and wellbeing. They also provide helpful insights into the ways in which our understanding of neurobiology can inform our counselling practice. A comprehensive exploration of these theories is beyond the scope of this chapter. However, in the following sections we will introduce some key principles associated with these theories to illustrate how they are helpful in making the link from neurobiology to the counselling context.

Polyvagal Theory

Polyvagal Theory has its foundations in neurobiology and neurophysiology. It is a multifaceted theory which offers (a) a descriptive model of the mammalian nervous system; and (b) a series of hypotheses which have the potential to contribute to enhancements of mental and physical health (Porges, 2021). In its simplest form, and most relevant to counsellors/therapists, Polyvagal Theory provides an explanatory framework for the mutually influencing relationships between perceptions of safety, neurophysiological functioning, emotional responses, social interactions, and physical and psychological health outcomes.

Foundational to Polyvagal Theory is the idea that, rather than safety being a subjective experience, “feelings of safety have a measurable underlying neurophysiological substrate” (p. 2). These feelings of safety are the result of the subjective interpretation of nervous system indicators derived from internal and external cues, which can be understood within a hierarchical model of self-regulation (Porges et al., 1994).

The hierarchy of safety cues begins with internal neurophysiological processes and progresses to the evaluation of external cues (Porges, 2022). The processes of neuroception and co-regulation are fundamental to this hierarchical model and represent key concepts within Polyvagal Theory (Porges et al., 1994). Together, the concepts of a hierarchical system, neuroception and co-regulation help to explain the relationship between neurophysiology and emotional and behavioural outcomes, as follows:

- Hierarchy of the autonomic nervous system – In states of autonomic nervous system arousal, access to higher brain centres (i.e. the prefrontal cortex) is reduced, in favour of the mechanisms responsible for managing the perceived threat to survival (i.e. the limbic system). In this way, we lose our capacity to problem solve and regulate our emotions effectively when our autonomic nervous system is in a state of mobilisation or immobilisation. It is not until the nervous system is returned to homeostasis that we can access those higher centres and engage meaningfully in social interactions.

- Neuroception – According to Polyvagal Theory, neuroception is an unconscious process whereby the autonomic nervous system scans the inner and outer environment to identify risks (Porges, 2009). This discernment of risk is communicated instantaneously through the nervous system, and influences behaviour, thoughts, and feelings without conscious awareness.

- Co-regulation – When two people are in communication with one another, each holds the capacity to influence the nervous system arousal of the other. In Polyvagal Theory, this mutually influencing process is known as co-regulation. Our social engagement system enables us to send messages of threat or non-threat to others via our facial expressions, movements, and vocal intonations.

Table 1 provides an overview of the hierarchical model of self-regulation, proposed by Porges (1996).

Table 1. Hierarchical Model of Self-Regulation

| Level | Processes |

|---|---|

| Level I | Neurophysiological processes characterised by bidirectional communication between the brainstem and peripheral organs to maintain physiological homeostasis. |

| Level II | Physiological processes reflecting the input of higher nervous system influences on the brainstem regulation of homeostasis. These processes are associated with modulating metabolic output and energy resources to support adaptive responses to environmental demands. |

| Level III | Measurable and often observable motor processes including bodily movements and facial expressions. These processes can be evaluated in terms of quantity, quality, and appropriateness. |

| Level IV | Processes that reflect the coordination of motor behaviour, emotional tone, and bodily state to successfully negotiate social interactions. Unlike those of Level III, these processes are contingent with prioritised cues and feedback from the external environment. |

Note. From “Physiological regulation in high-risk infants: A model for assessment and potential intervention” by S. W. Porges, 1996, Development and Psychopathology, 8(1), p. 52. (https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400006969). Copyright 1996 by Cambridge University Press. Reprinted with permission.

According to Polyvagal Theory, the interpretation of the cues attained from each of the levels in the hierarchical model of self-regulation result in three main response states, as follows:

- Fight-or-Flight/Mobilisation – occurs when a threat is perceived.

- Collapse/Immobilisation – is associated with feeling numb or disconnected from the external environment in situations of overwhelm or powerlessness.

- Social engagement/Ventral vagal – occurs when we feel relaxed and open to social interactions.

Figure 4 depicts these responses and the physiological and emotional states associated with them.

Figure 4. Polyvagal Theory Responses

Implicated in these responses is the vagus nerve (also known as the tenth cranial nerve), which facilitates rapid communication between the brain and organs (Porges et al. 1994). The vagus nerve is involved in key functions related to these response states, including regulating heart rate, breathing, digestion, and emotional responses. Measurable differences in vagal nerve tone have been associated with each of the response states (Porges et al. 1994) and there is a growing body of research evaluating the effectiveness of vagal nerve stimulation for a range of health conditions, including physical and psychological disorders (Goggins et al., 2022; Porges, 2023). We will explore the implications of Polyvagal Theory for counselling practice in a subsequent section.

Interpersonal Neurobiology

Interpersonal Neurobiology (Siegel, 2020) can be understood as a conceptual framework influenced by many disciplines that informs and advances understanding of mental and physical health and wellbeing. Interpersonal Neurobiology incorporates influences from several disciplines, including mathematics, physics, biology, psychology, linguistics, sociology, and anthropology (Siegel, 2019).

Foundational to Interpersonal Neurobiology is the question, “What is the mind?” and, drawing from a range of disciplines, it is proposed that energy is the basis of the mind (c.f. the structure of the brain). Further, Interpersonal Neurobiology purports that the mind can be considered both a conduit and a constructor of energy flow. Energy may take the form of sensory inputs or information (energy with meaning) and is the delivery mechanism of intra- and inter-individual communication. (Siegel, 2019)

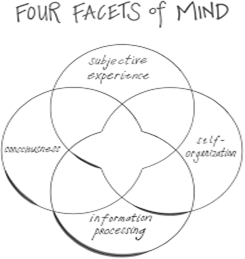

Models of the mind derived from other disciplines have typically included three elements: subjective experience, consciousness, and information processing. A key addition of the conceptualisation of the mind as presented by Interpersonal Neurobiology is the idea of self-organisation (Siegel, 2019). According to Interpersonal Neurobiology, self-organisation relates to the capacity of the system to optimise its own functioning by responding to cues (i.e. energy) received by the system. An effective self-organising system is capable of integration, which is the process of accommodating the simultaneous differentiation of, and linking between, separate parts of the system. The four facets of the mind, as proposed by Interpersonal Neurobiology are represented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. The Four Facets of the Mind

This model suggests that the mind can be best understood as a system that is comprised of four facets, which relies on the flow of energy (in the form of sensory inputs and information) for its function. Pivotal to that system is its capacity to organise and act upon those energy inputs in meaningful ways. Interpersonal Neurobiology hypothesises that integration, whereby the elements of the system are simultaneously differentiated from one another and linked in meaningful ways, is the mechanism by which self-organisation is possible. According to Siegel (2019), “If the mind is, in part, the emergent self-organising process that regulates the flow of energy and information, then integration would be the mechanism of a healthy life” (p. 229).

Further to this, Siegel and Drulis (2023) propose that integration is a key indicator of mental health. When the mind adapts and incorporates energy inputs reflexively and in ways that sustain self-organisation, that system (including the body and the mind) is optimised for healthy functioning. When integration is not effective, and the processing of energy inputs is either too rigid or too chaotic, poor health ensues. Siegel (2019) proposes that many diagnostic categories within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) can be understood through the lens of rigid or chaotic (and therefore ineffective) attempts at integration.

The hypothesis that integration is a mechanism for optimising health has been found to be a helpful framework for understanding the health of the mind, body, and brain on an intrapersonal level. It has also been extended as a mechanism for optimising health in relationships, communities, and even in the context of the planet’s ecosystems (Siegel & Drulis, 2023). A growing body of evidence also supports the utility of integration as a framework for understanding the aetiology and presentation of a range of disorders (Zhang & Raichle, 2010) and as an explanatory mechanism for some of the quantifiable impacts on the brain that have been observed in the aftermath of adverse life events, such as developmental trauma (Teicher et al., 2003; Teicher et al., 2004; Teicher et al., 2016; Teicher et al., 2020).

Taken together, these studies indicate that, in addition to structural anomalies in the brain being associated with psychiatric diagnoses, there is evidence of reduced connectivity between brain structures, which can be understood as disrupted or failures of integration. This disrupted integration can account for trauma-related sequelae, such as explicit memories being absent or fragmented while implicit memories may be intrusive and impactful on functioning (Siegel & Sieff, 2015). In this context, it can be inferred that there was a lack of integration between the parts of the brain responsible for encoding the explicit memory and the parts of the brain that encoded the emotional experience (Siegel, 2019). Further support for the hypothesis that integration is a helpful mechanism for understanding healthy and unhealthy functioning can be found in the conclusions of the Human Connectome Project, which identified the interconnectedness of the brain was associated with every measure of wellbeing included in that study (Smith et al., 2015).

Implications for Practice

In our preliminary consideration of the macro-anatomy and functioning of the brain and nervous system, together with an introduction to Polyvagal Theory and Interpersonal Neurobiology, we have learned some key principles that demonstrate measurable links between an individual’s neurobiology and their inner and outer experiences. Together, this body of knowledge suggests a range of implications for how we can engage meaningfully and supportively with our clients in a therapeutic context. Although it could be suggested that this knowledge is relevant to all aspects of the counselling process, a few key implications will be noted below.

Cultivating Connection

By identifying the mechanisms by which neurobiology influences, and is influenced by, the external environment, we can appreciate the importance of monitoring our own nervous system activation, as well as that of our clients’. Recognising that the ideal state for meaningful engagement, as identified by Polyvagal Theory, is social engagement/ventral vagal, we can take steps to ensure that, prior to each session, our neurobiology is aligned, to the greatest extent possible, with this state.

Consistent with the basic tenet of Interpersonal Neurobiology that energy is the mechanism by which all inner and outer experiences are conveyed, we can acknowledge that the energetic exchange that occurs between client and counsellor will be mutually influencing. It is also helpful to remain cognisant of this throughout each session, and to take steps to down-regulate if we notice ourselves becoming heightened. Interpersonal Neurobiology offers a useful acronym (PART) that captures the ideal conditions under which meaningful connection can occur, as follows:

- Presence – being open to what is arising as it arises

- Attunement – focusing with respect on the differentiated inner experience of members of a relationship

- Resonance – alteration of the internal state of members of a relationship such that they influence one another, yet retain their differentiated nature as they become linked

- Trust – the state within a person or within a relationship of being open to others without defensiveness (Siegel, 2019, pp. 233-234).

Facilitating Understanding of the Story Behind the Story

In addition to paying attention to our own and our clients’ neurophysiological indicators during a counselling session, our understanding of neurobiology has implications for understanding our clients’ stories. When we hear our clients’ stories, and apply our knowledge of neurobiology to those stories, we can develop testable hypotheses about our clients’ experiences.

For example, applying knowledge of the impact of adverse events on the development of memories and the ways in which the structure and function of the brain can be affected by trauma, provides important insights into the ways in which our clients may have experienced and made sense of their experiences, as well as the potential consequences of those events. This is not to suggest that we are seeking to overlay a diagnostic framework onto our clients’ stories. Rather, understanding the neurobiological implications of adverse events at different times across the lifespan can expand our capacity for supporting our clients.

Using the “Integration” concept as an Organising Principle for Case Conceptualisation and Treatment Planning

As identified by Siegel (2019), the concept of integration offers a helpful framework for understanding health within and between individuals. The core tenet of integration is that it represents a complex system’s capacity to accommodate the differentiation of individual components within the system, as well as linkages between those differentiated parts, to facilitate effective functioning of the system. This dual process of differentiation and linkage can be applied across nine key domains that contribute to health, as follows:

- Consciousness – The experience of differentiating the knowing from the knowns of what we are aware of and then linking to one another.

- Bilateral – The honouring of the differentiated functions of the left and right hemispheres and then linking them together, especially as the left has a narrow deep-dive focus of attention and the right a broader, context embracing focus.

- Vertical – Linking the body’s signals and the lower neural regions of the brainstem and limbic area to the higher cortical regions’ involvement in the experience of consciousness.

- Memory – Linking the differentiated elements of implicit memory to the autobiographical and factual experience of explicit memory processing.

- Narrative – Making sense of memory and experience such that one finds meaning in events that have occurred and how they made an impact on one’s life across time.

- State – Respecting the differentiated states of mind that make up the wide array of clusters of memory, thought, behaviour, and action that are the nature of our multilayered selves and then finding a way to honour and link them without losing their essence.

- Interpersonal – Honouring one another’s inner experience while linking in respectful, compassionate communication.

- Temporal – The capacity to represent ‘time’ or change in life and reflect on this ‘passage of time’ leading to many differentiated ways of experiencing crucial existential themes in life: finite versus timeless, transient versus permanent, predictable versus unpredictable, life versus death.

- Identity – The sense of agency and coherence that may be associated with a feeling of belonging, one that can be encased by the skin or broadened across space and time” (Siegel, 2019, p. 235).

Although an in-depth exploration of each of these domains is beyond the scope of this chapter, it is worth noting the ways in which this conceptualisation of integration across these domains is consistent with our knowledge of neuroanatomy, neurophysiology, and the tenets of Polyvagal Theory, and can inform all facets of the counselling process, including case conceptualisation and treatment planning.

Conclusion

This chapter has presented some key aspects of neurobiology, as they are applicable for counsellors. It included an overview of the structure and functioning of the brain and the nervous system, and outlined two helpful theoretical approaches that draw from a range of disciplines to provide descriptive models and generate testable hypotheses regarding the interplay between neurobiology and human functioning.

It is not suggested that this is an exhaustive overview of these topics, or that these are the only theories that are relevant and applicable to counsellors. Rather, it was intended to introduce these key concepts as foundational knowledge, and you are encouraged to explore beyond this chapter. To that end, some recommended readings are listed below. You are also encouraged to consider how the contents of this chapter is complementary to the other theories and approaches discussed in this book, and to recognise the importance of integrating this knowledge across all facets of your counselling practice.

Reflective Questions

- Why is it important for counsellors/therapists to have an understanding of neurobiology?

- Reflect upon the quote from Dan Siegel at the beginning of this chapter. Why do you think this quote was chosen to preface this chapter?

- How would you describe the ways in which our nervous system influences our social interactions (and vice versa)?

Optional Activities

- Search for and implement either a breathing exercise or a vagal nerve exercise to practise regulating your nervous system.

As we have learned in this chapter, the ability to regulate the nervous system is a powerful and effective means of reducing stress and enhancing our capacity to engage in meaningful social interactions. With that in mind, there are many simple exercises that you may like to utilise yourself, in preparation for your client work, during sessions to support your clients, or you can recommend them to your clients as part of their between-session homework.

Irrespective of how you choose to use these exercises, they are a helpful addition to your therapeutic toolbox, both for regulating your own nervous system so you are ready to engage fully with your clients, and as a way of providing clients with strategies for self-regulation. There are many exercises you can use in this regard, and in many ways, you are limited only by your imagination.

The idea is to engage in a practice that calms your body and mind and brings you to the present moment. This can be as simple as taking a few slow, deep breaths (and it is even better if you do so with your eyes closed, as that will signal to your nervous system that you are safe), or engaging each of the senses in turn, by identifying what you can see, hear, smell, touch and taste. Another great option, which is informed by Polyvagal Theory, is vagal nerve stimulation exercises. There are many options for this, and a simple internet search for “vagal nerve exercises” will provide you with a wide array of videos and other resources to guide you through these exercises.

- Reflect upon a challenging interpersonal encounter you have experienced.

Apply your knowledge of Polyvagal Theory and/or Interpersonal Neurobiology to that situation and consider how those theories provide a deeper or more meaningful understanding of the interaction.

References

Akil, H., & Nestler, E. J. (2023). The neurobiology of stress: Vulnerability, resilience, and major depression. PNAS, 120(49). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2312662120

Arain, M., Haque, M., Johal, L., Mathur, P., Nel, W., Rais, A., Sandhu, R., & Sharma, S. (2013). Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 9, 449-461. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S39776

Babakr, Z., Mohamedamin, P., & Kakamad, K. (2019). Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory: Critical review. Education Quarterly Reviews, 2(3), 517-524. https://doi.org/10.31014/aior.1993.02.03.84

Bazira, P. J. (2021). An overview of the nervous system. Surgery (Oxford), 39(8), 451-462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpsur.2021.06.012

Bethlehem, R. A. I., Seidlitz, J., White, S. R., Vogel, J. W., Anderson, K. M., Adamson, C., Adler, S., Alexopoulos, G. S., Anagnostou, E., Areces-Gonzalez, A., Astle, D. E., Auyeung, B., Ayub, M., Bae, J., Ball, G., Baron-Cohen, S., Beare, R., Bedford, S. A., Benegal, V., … & Vetsa. (2022). Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature, 604(7906), 525-533. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04554-y

Bui, T., & Das, J. M. (2023, 24 July). Neuroanatomy, cerebral hemisphere. Stat Pearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549789/

Collins, A., & Koechlin, E. (2012). Reasoning, learning, and creativity: Frontal lobe function and human decision-making. PLoS Biology, 10(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001293

Dziedzic, T. A., Bala, A., & Marchel, A. (2021). Cortical and subcortical anatomy of the parietal lobe from the neurosurgical perspective. Frontiers in Neurology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.727055

Fang, Y., Sun, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, T., Hao, W., & Liao, Y. (2022). Neurobiological mechanisms and related clinical treatment of addiction: A review. Psychoradiology, 2, 180-189. https://doi.org/10.1093.psyrad/kkac021

Firat, R. B. (2019). Opening the “Black Box”: Functions of the frontal lobes and their implications for sociology. Frontiers in Sociology, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00003

Fuchs, E., & Flügge, G. (2014). Adult neuroplasticity: More than 40 years of research. Neural Plasticity, 2014, 541870. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/541870

Gilbert, P. (2019). Psychotherapy for the 21st century: An integrative, evolutionary, contextual, biopsychosocial approach. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 92, 164-189. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12225

Glasper, E. R., & Neigh, G. N. (Eds.). (2019). Experience-dependent neuroplasticity across the lifespan: From risk to resilience. Frontiers Media SA. https://doi.org/10.3389/978-2-88945-782-3

Goggins, E., Mitani, S., & Tanaka, S. (2022). Clinical perspectives on vagus nerve stimulation: Present and future. Clinical Science, 136, 695-709. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20210507

Gonda, X., Dome, P., Erdelyi-Hamza, B., Krause, S., Elek, L. P., Sharma, S. R., & Tarazi, F. I. (2022). Invisible wounds: Suturing the gap between the neurobiology, conventional and emerging therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 61, 17-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2022.05.010

Güntürkün, O., Ströckens, F., & Ocklenburg, S. (2020). Brain lateralization: A comparative perspective. Physiological Reviews, 100(3), 1019-1063. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00006.2019

Haahr-Pedersen, I., Perera, C., Hyland, P., Vallieres, F., Murphy, D., Hansen, M., Spitz, P., Hansen, P., & Cloitre, M. (2020). Females have more complex patterns of childhood adversity: Implications for mental, social and emotional outcomes in adulthood. Psychotraumatology, 11, https:doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1708618

Herman, J. P., McKlvneen, J.M., Ghosal, S., Kopp, B., Wulsin, A., Makinson, R., Scheimann, J., & Myers, B. (2016). Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response. Comprehensive Physiology, 6(2), 603-621. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c150015

Hertenstein, E., Trinca, E., Schneider, C. L., Wunderlin, M., Feher, K., Riemann, D., & Nissen, C. (2021). Augmentation of psychotherapy with neurobiological methods: Current state and future directions. Neuropsychobiology, 80, 437-453. https://doi.org/10.1159/000514564

Hosseini-Kamkar, N., Farahani, M. V., Nikolic, M., Stewart, K., Goldsmith, S., Soltaninejad, M., Rajabli, R., Lowe, C., Nicholson, A. A., Morton, B., & Leyton, M. (2023). Adverse life experiences and brain function: A meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging findings. JAMA Network Open: Psychiatry, 6(11). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.40018

Jawabri, K. H., & Sharma, S. (2023, 24 April). Physiology, Cerebral cortex functions. Stat Pearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538496/

Jimsheleishvili, S., & Dididze, M. (2023, 24 July). Neuroanatomy, Cerebellum. Stat Pearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538167/

Juruena, M.F., Bourne, M., Young, A.H., & Cleare, A.J. (2021). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction by early life stress. Neuroscience Letters, 759, 136037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2021.136037

Kamiya, K. & Abe, O. (2020). Imaging of posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America, 30(1), 115-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nic.2019.09.010

Kaushal, P.S., Saran, B., Bazaz, A., & Tiwari, H. (2024) A brief review of limbic system anatomy, function, and its clinical implication. Santosh University Journal of Health Sciences, 10(1), 26-32. https://doi.org/10.4103/sujhs.sujhs_19_24

Kuhn, H. G., Palmer, T. D., & Fuchs, E. (2001). Adult neurogenesis: A compensatory mechanism for neuronal damage. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 251(4), 1705-1711.

Maldonado, K. A., & Alsayouri, K. (2023, 17 March). Physiology, Brain. Stat Pearls Publishing. Retrieved 19 February 2024 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551718/

Mateos-Aparicio, P., & Rodriguez-Moreno, A. (2019). The impact of studying brain plasticity. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2019.00066

McGilchrist, I. (2010). Reciprocal organization of the cerebral hemispheres. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(4), 503-515. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.4/imcgilchrist

McHenry, B., Parmentier-Sikorski, A., & McHenry, J. (2013). A counselor’s introduction to neuroscience. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203072493

Murnane, K.S., Edinoff, A.N., Cornett, E.M., & Kaye, A.D. (2023). Updated perspectives on the neurobiology of substance use disorders using neuroimaging. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 14, 99-111. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S362861

Patel, A., Biso, G., & Fowler, J. B. (2023, 24 July). Neuroanatomy, Temporal lobe. Stat Pearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519512/

Petrocchi, N., & Cheli, S. (2019). The social brain and heart rate variability: Implications for psychotherapy. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 92, 208-223. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12224

Poeppel, D., & Idsardi, W. (2022). We don’t know how the brain stores anything, let alone words. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(12), 1054-1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2022.08.010

Porges, S. W. (1996). Physiological regulation in high-risk infants: A model for assessment and potential intervention. Development and Psychopathology, 8(1), 43-58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400006969

Porges, S. W. (2021). Polyvagal theory: A biobehavioral journey to sociality. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology, 7, 100069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpnec.2021.100069

Porges, S. W. (2022). Polyvagal theory: A science of safety. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2022.871227

Porges, S. W. (2023). The vagal paradox: A polyvagal solution. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology, 16, 100200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpnec.2023.100200

Porges, S. W., Doussard-Roosevelt, J. A., & Maiti, A. K. (1994). Vagal tone and the physiological regulation of emotion. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2/3), 167-186.

Rehman, A., & Al Khalili, Y. (2023, 24 July). Neuroanatomy, Occipital lobe. Stat Pearls Publishing. Retrieved 19 February from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544320/

Rogers, L. (2021). Brain lateralization and cognitive capacity. Animals, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11071996

Ross, E. D. (2021). Differential hemispheric lateralization of emotions and related display behaviors: Emotion-type hypothesis. Brain Sciences, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11081034

Sherin, J. E., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder: The neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(3), 263-278. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.2/jsherin

Siegel, D. J. (2019). The mind in psychotherapy: An interpersonal neurobiology framework for understanding and cultivating mental health. [Special issue paper]. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 92, 224-237. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12228

Siegel, D. J. (2020). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. (3rd ed.). Guilford Publications. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uql/detail.action?docID=6172778

Siegel, D. J., & Drulis, C. (2023). An interpersonal neurobiology perspective on the mind and mental health: Personal, public, and planetary well-being. Annals of General Psychiatry, 22(5). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-023-00434-5

Siegel, D. J., & Sieff, D. F. (2015). Beyond the prison of implicit memory: The mindful path to well-being. In D. F. Sieff (Ed.), Understanding and healing emotional trauma: Conversations with pioneering clinicians and researchers. (pp. 137-159). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315747231-8

Smith, S. M., Nichols, T. E., Vidaurre, D., Winkler, A. M., Behrens, T. E. J., Glasser, M. F., Ugurbil, K., Barch, D. M., Van Essen, D. C., & Miller, K. L. (2015). A positive-negative mode of population covariation links brain connectivity, demographics and behavior. Nature Neuroscience, 18(11), 1565-1571. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4125

Teicher, M. H., Andersen, S. L., Polcari, A., Anderson, C., Navalta, C. P., & Kim, D. M. (2003). The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 27, 33-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7634(03)00001-1

Teicher, M. H., Dumont, N. L., Ito, Y., Vaituzis, C., Giedd, J. N., & Andersen, S. L. (2004). Childhood neglect is associated with reduced corpus callosum area. Biol Psychiatry, 56(2), 80-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.016

Teicher, M. H., Ohashi, K., & Khan, A. (2020). Additional insights into the relationship between brain network architecture and susceptibility and resilience to the psychiatric sequelae of childhood maltreatment. Adversity and Resilience Science, 1, 49-64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-020-00002-w

Teicher, M. H., Samson, J., Anderson, C., & Ohashi, K. (2016). The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function and connectivity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17, 652-666. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn,2016.111

Thumfart, K. M., Jawaid, A., Bright, K., Flachsmann, M., & Mansuy, I. M. (2022). Epigenetics of childhood trauma: Long term sequelae and potential for treatment. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 132, 1049-1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.10.042

Tierney, A. L., & Nelson, C. A. (2009). Brain Development and the Role of Experience in the Early Years. Zero to Three, 30(2), 9-13.

Waxenbaul, J. A., Reddy, V., & Varacallo, M. (2023, 24 July). Anatomy, autonomic nervous system. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539845

Wilson, R. Z. (2014). Neuroscience for counsellors: Practical applications for counsellors, therapists and mental health practitioners. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Zhang, D., & Raichle, M. E. (2010). Disease and the brain’s dark energy. Nature Reviews Neurology, 6, 15-28. https://doi.org/10.1038.nrneurol.2009.198