10 Counselling and Psychotherapy Integration

Denis O'Hara

“Psychotherapy integration is about finding what works, for whom, and under what circumstances.” – John C. Norcross

Key Takeaways

This chapter explores how counsellors and psychotherapists approach the dynamic task of integrating different theories of psychotherapy. The chapter covers several key features of integration as listed below:

- The emergence of psychotherapy integration from research on common factors of therapeutic change is explained.

- It is asserted that integration is based on the recognition that no one theory provides all the available knowledge, skills, and processes to facilitate change.

- Different established approaches to psychotherapy integration are described.

- The place and contribution of theory within the context of counselling and psychotherapy is explored.

- The notion that therapists apply therapy in their own idiosyncratic fashion is highlighted.

- The place of Practice Frameworks is examined, and examples of several Practice Frameworks are described and discussed.

Introduction

In Chapter 2, we introduced the common factors involved in any psychological change process. Research has identified several common factors with the formulation by Lambert (1992) the best known. This early arrangement identified four broad categories of extra therapeutic or client factors, the therapeutic relationship, theory, hope and expectancy. Each of these factors contains within it a further set of more specific sub-factors (Grencavage, & Norcross, 1990; Leibert, 2011). As change research progresses, we know more and more about the finer aspects of change. For example, we now know that the category of client factors involves such elements as client personality, coping style, and problem type. Similarly, we know that relationship factors involve empathy, congruence, goal consensus, and attachment style, to name a few (Norcross, 2019). The recognition of the place of common factors in counselling and psychotherapy has deepened our appreciation of the breadth of ideas and processes involved in psychological change.

While theory is listed as one of the common factors, it is not regarded as the singular explanation for how and why psychological change occurs. This is not to say that theory is not highly significant. We noted in Chapter 2 that there exist specific factors of change. This is the notion that while there are common factors that are always in operation, in certain situations and with specific presenting conditions, some interventions or approaches tend to produce better results (Cuijpers et al., 2014; Zilcha-Mano et al., 2019). Hence, we should always appreciate the fact that psychological change is a complex process and that we need to maintain an open mind about what are the best ways of working with individuals struggling with a wide range of challenging issues.

The recognition that many factors contribute to change shifted the counselling field away from a concern about which theory/therapy is the most effective to an awareness that any bona fide therapy must, at least, be facilitating some dimension of the common factors of change, as well as potentially contributing a unique or specific change factor. This awareness gave rise to what is more generally known as the psychotherapy integration movement (Norcross & Newman, 1992).

Psychotherapy integration begins from the premise that all good theories add something valuable to our understanding of change. Integration was also spurred on by research which found that most counsellors and psychotherapists draw on a wider range of theory than their espoused theories of practice (Boswell et al., 2009). Hence, while a practitioner might assert, for example, that they are a CBT therapist or narrative therapist, each tends to borrow ideas from other approaches when the need arises. The fact that therapists draw on a range of theories raised the question, “How do therapists integrate different theories into their practice?” What guides therapists’ practice is important for several reasons. Firstly, in seeking to be scientist-practitioners as well as reflective-practitioners, therapists want to be able to establish the discipline’s academic credentials and be able to measure and prove what works and what does not work. Of course, this is a laudable aim but one not so easily achieved in a field where the concern and focus is not principally on organic disease but on less tangible inner human dynamics. Secondly, if we can identify how therapists integrate and facilitate psychological change, then it may be possible to replicate the process. Thirdly, if integration is researched, then it may be possible to identify the most effective form of integration.

As the field progressively realised the importance of integration, new journals and professional associations were established to provide sites for professional dialogue. As early as 1983, the Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Integration (SEPI) was established eventually sponsoring the creation of the Journal of Psychotherapy Integration in 1991. These have been important vehicles for research and dissemination of ideas about integration. One of the outcomes of these dialogues was the identification of several different approaches to psychotherapy integration. Apart from a recognition of the place that the common factors play, three other major forms of integration were proposed.

Technical Eclecticism

Early considerations of integration were focused on eclecticism. Eclecticism is based on the idea that a therapist can select strategies and interventions from a breadth of therapies as they see fit. The fact that it had been demonstrated that therapists do draw on many therapeutic approaches supported the viability of eclecticism (Norcross, & Goldfried, 2005). A more specific form of eclecticism made famous by Arnold Lazarus (1981) is known as technical eclecticism. Lazarus argued that a general eclecticism is not a sound foundation for the practice of counselling and psychotherapy as it has no firm rationale for the selection of strategies from different approaches. Instead, Lazarus argued that strategies should be selected based on evidence of their respective efficacy. In other words, if an intervention from a particular therapeutic approach had been demonstrated in research to be effective, especially if it was demonstrated to be more effective than other strategies, then that is a firm rationale for its selection. An illustrative example often used is the effectiveness of exposure therapy for anxiety disorders, especially social anxiety (Parker et al., 2018).

While technical eclecticism has much to recommend it, one of the more subtle issues inherent in the approach concerns its assumptions about what constitutes research evidence. The general assumption is based on a strictly empirical approach highly reliant on randomised controlled trials (RCTs). While RCTs contribute significantly to our knowledge base, it can also be argued that there is much valid evidence that is provided by other quantitative and qualitative methodologies. In this respect, how one delimits what is regarded as evidence also limits the range of interventions that meet the benchmark of ‘technical’. It is important to realise that how one views evidence is circumscribed by one’s worldview or metatheoretical assumptions.

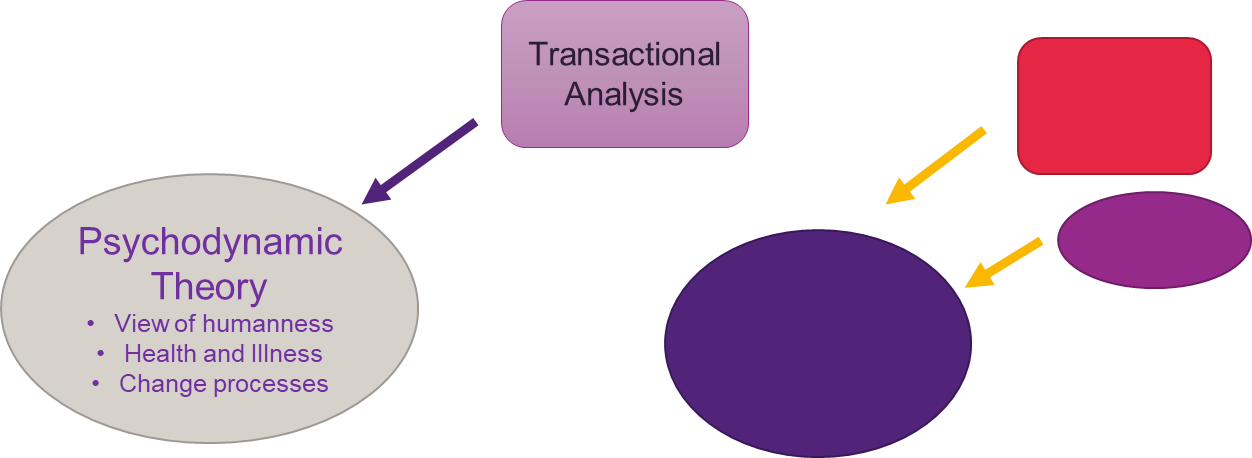

Assimilative Integration

Another approach to psychotherapy integration is known as assimilative integration. This approach proposed by Stanley Messer (1992; 2001) suggests that therapists naturally have preferred metatheoretical assumptions whether they are clearly aware of them or not and, as such, naturally are drawn to theories of counselling and psychotherapy that are consistent with these assumptions. This being the case, Messer argues that a counsellor will have a dominant theory that informs their practice. However, as all theories are limited, singular theories are unlikely to have the necessary framework to explain all human problems. Hence, while psychodynamic theory, for example, may be very good at providing an understanding of a client’s history and unconscious processes, it may not be as effective in explaining the impact of biochemical rewards active in drug addiction. With this realisation, Messer argued that therapists are predominantly informed by their dominant theoretical approach but draw into their respective base approach strategies, interventions, and ideas from other theories that meet specific needs of the individual client. This is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Assimilative Integration

A therapist’s base theory provides the main category or frame of understanding of such key notions as:

- What it is to be human.

- How human health and illness is understood

- How therapeutic change occurs

Answers to these questions provides the main foundation upon which individual therapists operate. The secondary theory or theories are understood to be inculcated into the base theory. However, Messer acknowledges that in assimilating ideas from an approach that has different worldview assumptions, the base theory is adjusted or changed. While the dominant or base theory remains, it is reorganised to accommodate the ideas and strategies of the assimilated theory. It is often thought that assimilative integration is one of the most common approaches to integration as it provides a coherent worldview or metatheoretical foundation but also allows for ideas and practices from other theories to be incorporated making a therapist more adaptive to the needs of clients.

Theoretical Integration

Theoretical integration approaches the task of integration by drawing on key ideas from existing approaches to form a new comprehensive theory. As in assimilative integration, adherents of theoretical integration recognise the need to have some central or integrating frame, idea or device. In its purest form, the approach seeks to draw together the breadth of counselling theories into an overarching theory or metatheory. As theories are based on quite different assumptions, integrating such diversity requires going beyond the level of individual theories and identifying higher order conceptualisations of the human condition and of change approaches. This necessitates a keen awareness of metatheoretical assumptions as a way of accounting for change mechanisms. The perfect form of theoretical integration might almost be a theory about everything, but as this is not possible, a more modest expression of the approach is to construct theory based on some focusing device such as skills, procedures, categories or combinations of existing theories. Often such approaches are referred to as transtheoretical approaches.

One of the best known of such approaches is the ‘transtheoretical approach’ proposed by Prochaska and DiClemente (1983). The authors organise their model by identifying three main categories through which therapists filter their thoughts about clients and their presenting problems. The categories are:

- processes of change

- stages of change

- levels of change.

The details of these categories are listed below:

Processes of change

- Consciousness raising

- Counterconditioning

- Dramatic relief

- Environmental re-evaluation

- Helping relationships

- Reinforcement management

- Self-liberation

- Self-re-evaluation

- Social-liberation

- Stimulus control

Stages of change

- Pre-contemplative

- Contemplative

- Preparation

- Action

- Maintenance

Levels of change

- Symptom/situational problems

- Current maladaptive cognitions

- Current interpersonal conflicts

- Family/systems conflicts

- Long-term intrapersonal conflicts

In the processes of change, the therapist asks themselves and possibly the client what type of change is being sought or required. As several different types of change may be engaged, it is important for the therapist to know what to focus on in any given moment of therapy.

A seminal contribution and probably the most famous aspect of the transtheoretical model is the idea that change goes through stages. Associated with this idea is that the type of change sought, and the degree or level of change required, must match the stage of change an individual is ready to embrace. For example, the first stage of change is where a person is not clear about what change they are seeking but has some vague sense that some change is needed. This emerging awareness is usually one of the factors that draws a person to therapy as they have some perception that something is wrong and needs to be addressed. The next stage is where the nature of the change sought is pondered and gradually becomes clear. Later stages involve preparing for change, then acting to effect change, and finally maintaining the change achieved.

The final category in the model is the level of change. This refers to how deep or comprehensive the change sought might be. The first level of change focuses on symptom relief and situation changes. This level of change is regarded as much less challenging than the last level which refers to long-term relational change. Overall, the Transtheoretical Model of Change provides a very helpful way of thinking about the change process while at the same time allowing practitioners to draw on a breadth of counselling theories.

Pluralism

In more recent years, another approach proposed by Mick Cooper and John McLeod (2011) exemplifies a particular form of pluralism. All forms of pluralism are similar in that they encourage selection from the breadth of established therapies. This is consistent with the common factors view that any well-established therapy, when applied well, is likely to activate change processes. McLeod and Cooper agree while also drawing on ideas of the philosopher Rescher (1993) and others (McLellan, 1995; Derrida, 1974) who hold that any significant question can be answered in a variety of ways and that the diversity of nature cannot be reduced to a single principle. Drawing on these notions, McLeod and Cooper affirm that any established therapy could be used to address the needs of the client. What they suggest though is that the choice of therapy used in any given session of therapy has more to do with the client’s choice than the therapist’s choice. This is not to say that the therapist is not involved in the approach undertaken but it does highlight the very important common factor of the client and what they bring to the therapy process. Of course, counselling and psychotherapy are principally about the client and their concerns and intentions and not those of the therapist.

Cooper and McLeod (2011) set out a particular form of pluralism which, in its most basic design, has three stages or phases:

- Goals

- Tasks

- Methods

Given that the client is the focus of therapy, it is first important to establish what is the client’s goal for therapy. Why did they come and what would they like to achieve? While this might seem obvious, it is not presumed that clients are always crystal clear about what they want from therapy. Sometimes a client’s search is more intuitive than objectively clear. However, part of the therapy process is to help the client clarify their goal or goals.

Once the client’s goals for therapy are established, the next stage is to find agreement between the client and counsellor about the tasks that need to be undertaken to achieve the stated goals. Some examples of common tasks of therapy include:

- making meaning of problematic issues

- problem-solving

- changing behaviour

- negotiating life transitions

- dealing with difficult feelings and emotions

- dealing with difficult and painful relationships (Cooper & McLeod, 2011; Holtforth, & Grawe, 2002).

Having identified the tasks required to achieve the goals of therapy, the next stage is to agree on the theoretical approach or method employed. This is where the pluralist therapist is free to choose from an array of theories and approaches in cooperation with the client. McLeod and Cooper hold the view that the ‘way of working’ informed by a theoretical approach must be a way the client is in agreement with or at least can appreciate. In this respect, therapy is a co-creation between the therapist and client. If the client, for example, is more comfortable working in a cognitive way than in an affective or somatic manner then the therapist will draw on cognitive approaches to meet the client’s concerns.

One criticism of this form of pluralism is that it is not really a form of integration but a particular form of eclecticism. There is no real attempt in the pluralism described above to draw together different theories. However, allowing this, it is an important way of addressing the issue of “What is the most effective approach to counselling?”

Personal Approaches to Psychotherapy Integration

Another way of thinking about how practitioners approach psychotherapy integration apart from these meta-approaches is to acknowledge that almost everyone approaches integration in their own idiosyncratic way (O’Hara & Schofield, 2008). Unless one is a mono-theorist dedicated to only one theory, which we would argue is much harder to do than one might think, then most of us are either eclectic or integrative in our approach to therapy. Now this does not mean that we are fully aware of our approach. Practitioners probably range between those who freely choose or integrate by simply doing what feels right in the moment to those who integrate via quite sophisticated philosophical and structural approaches.

One of the curious things about counselling theories is that they are usually wonderful at helping us to think about the nature of humanness, assessment, diagnosis, and change principles but often not as strong at providing a detailed map of therapy. One of the obvious reasons for this is that each client and each presenting problem are unique making it impossible to simply provide a ‘generic fix’. The sheer complexity of human beings and of the therapeutic process requires us to constantly adjust to client needs often within the minute moments of the therapeutic encounter. However, having said this does not mean it is impossible to provide a general map or practice framework that helps therapists focus on what is important.

It is an interesting fact that as therapists we are naturally drawn to prefer different theoretical approaches over others. While we may change our mind over the course of our career, we will always have our preferred approaches. This is an interesting reality and less common in other professions, especially in the hard sciences. Even with an enormous volume of research in psychotherapy, we still cannot say, “It is proven that this is the very best approach”. So, while we know that certain strategies are highly effective, there is room for choice. The fact that we have preferred approaches begs the question, “On what basis do you choose?”

The answer to this question has many elements, some of which include, personality, past life experience, past therapy experience, cultural influences, client context, and more. As we are focusing on theory, it would be fair to say that it is something about the respective theory to which we are drawn that answers certain questions. Several of these questions were listed earlier in this chapter. Theory addresses at least three major concerns:

- What it is to be human.

- How human health and illness are understood.

- How therapeutic change occurs

The first of these concerns has been the topic of philosophy, theology, and anthropology for centuries. Whether you are aware of it or not you have firm views on the question of human nature or at least nascent (tentative or emerging) views. To help us think about this question, how would you answer the following questions?

Activity

If you think about your preferred theory or theories, you may notice that inherent in these theories is a preference for certain of these dichotic pairs. While this may be a somewhat simplistic approach to deep philosophical questions, it is true that we cannot escape having to respond to these questions in some way.

If we turn to the second of the concerns listed above, we are confronted by the issue of how human health and illness are understood. Again, this is a complex issue and has many elements. We know that some health conditions are principally genetic in origin while others have more to do with lifestyle. We might also add that lifestyle has both a personal and a sociocultural dimension. For example, our attitude to work has both personal and cultural features. Some people are workaholics due to their own predilection, and others are forced to work hard due to social and cultural imperatives. Related to this is the question of whether an illness is intrinsic to the person or extrinsic. A classic example here is depression. Is a person’s depression due to their inherited genes or to their sense of self, personal experiences, and lifestyle choices?

Our views about health and illness influence not just our choice of therapy but how we approach our clients. We will generally tend towards one end of the continuum below.

Of course, this will vary depending somewhat on the nature of the problem being addressed. The issue is further highlighted when we consider diagnosis. If we think a presenting problem is largely due to genetics, we are likely to understand the problem in terms of a diagnostic category. If, on the other hand, we see the problem as being due to the client’s sense of self, lifestyle, or social conditions then we will be less inclined to categorise in a diagnostic fashion. We could say that to a significant degree, the nature of a client’s problem is largely determined by the eye of the beholder.

The third concern regards our view of how therapeutic change occurs. This is very much influenced by our perspective on the first two concerns. It will also be influenced by our own experiences, personality, and training. Some of us will naturally default to a view of change as principally based on cognitions. For others it will be more about emotions and feeling states, and for others it will be about somatic or bodily states. Obviously, in realty, change is influenced by all these factors as well as by transpersonal issues such our understanding of the transcendent.

With all the above in mind, our assertion is that each counsellor brings to therapy their collective and embodied perspective on all these issues. We choose theories, whether intuitively or consciously, that best represent our views on these matters. Interestingly, even though we have our preferred approaches, when working with our clients we typically do not follow a purely prescribed theoretical approach. Instead, we draw on theory but adjust it to the needs of the client in the moments of therapy. We suggest that while this is a good thing, it presents us with a problem. If we do not follow our preferred theory to the letter, then what directs our approach to therapy? The short answer is all the things we have discussed in this chapter and more. While this is true it leaves us with the need for direction. What are the steps that guide us?

Implications for Practice

Practice Framework

One way to address this question of direction is a practice framework. A practice framework is essentially an overview map of the steps and stages of therapy. It is influenced by theory but is broader in scope, allowing for adjustments as required. Practice Frameworks come in varying degrees of specificity; some are quite minimalist and others very detailed. An example of a minimalist framework is that provided by Ivey and others (Ivey, et al., 2016) in what they refer to as the Five Stages of the Counselling Session:

- Empathic relationship or rapport building

- Story and strengths

- Goals

- Re-story

- Action.

As you can see the authors recommend that therapists be guided by these therapy stages. However, the approach is general enough that therapists are at liberty to incorporate strategies from their preferred theories.

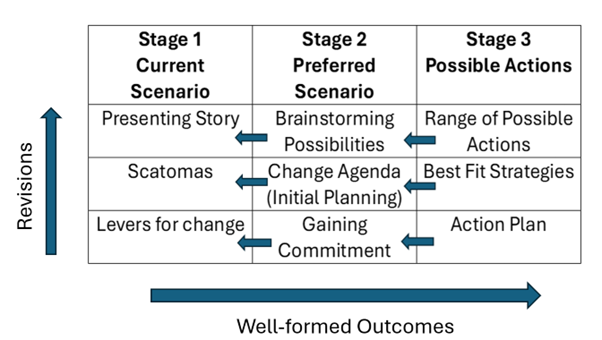

Another Practice Framework by Egan is more detailed. His model can be seen in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Egan’s Model

Egan envisions therapy moving across three broad stages each involving three sub-components which are dynamic and can be returned to or adjusted as the therapy progresses. This model is often called a problem-solving approach and like all frameworks has its own theoretical assumptions and preferences.

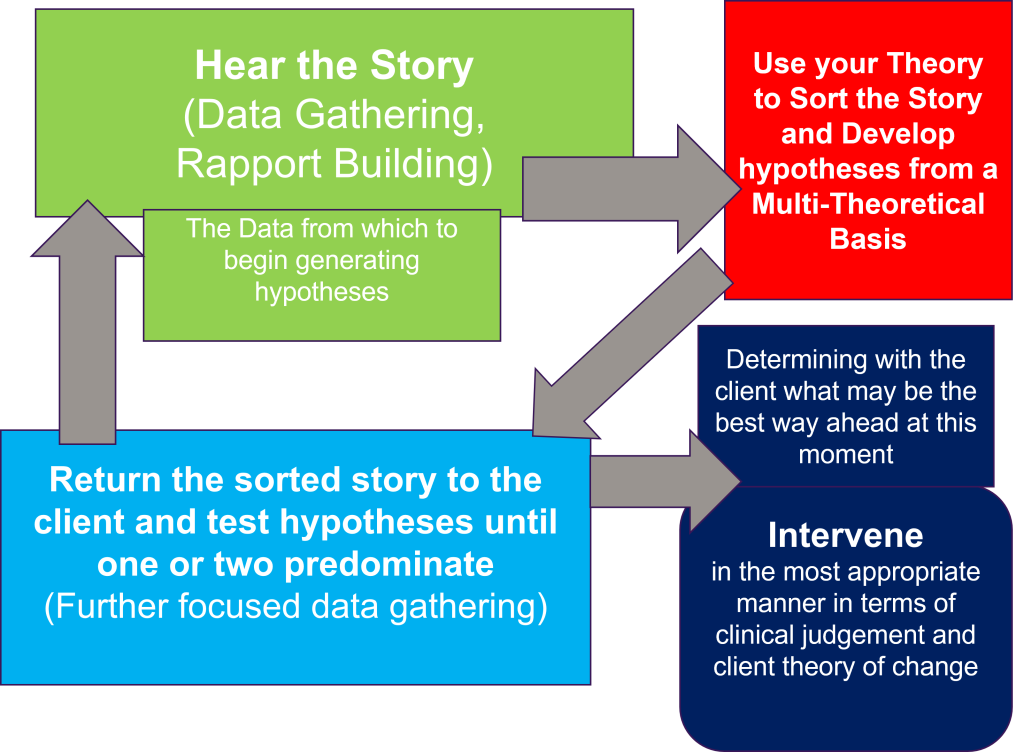

One of the Practice Frameworks used at The University of Queensland in the education of counsellors and psychologists can be seen in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. UQ Practice Framework

This framework provides a helpful guide or map to the main stages or steps within the therapeutic process. You can see that the process is dynamic in that the next step depends on achieving the preceding step and, if necessary, returning to it until clarification is reached. A central emphasis is placed on deeply listening and hearing the client’s story and then cocreating a hypothesis about the nature of the problem.

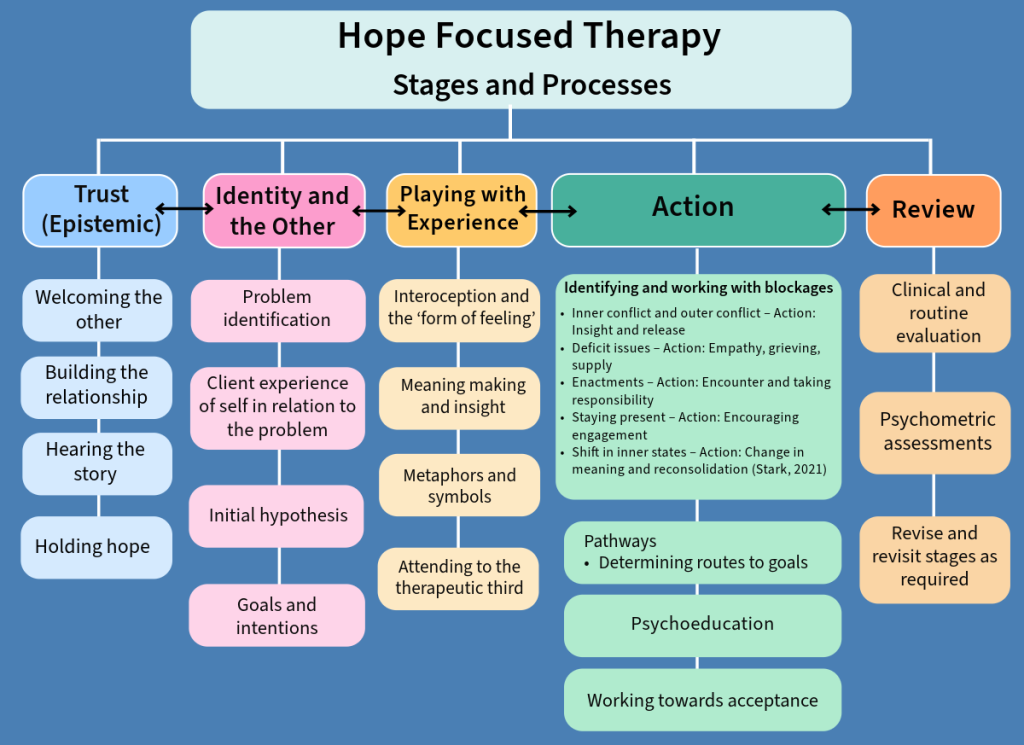

Another practice framework comes from hope focused therapy (O’Hara, 2013; O’Hara & O’Hara, 2020) which while an integrative approach is strongly influenced by interpersonal psychodynamic and humanistic theories and the important place that facilitating hope plays within the therapeutic process. A basic outline of the Practice Framework is provided in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4. Hope Focused Therapy Practice Framework

The mnemonic TIPAR is an easy way to remember the stages of therapy, Trust, Identity, Play, Action and Review. The establishment of trust and the therapeutic relationship is an essential foundation for hearing the client’s story. As the problem story is told the therapist must apply deep listening while holding hope for the client especially when the client is struggling to maintain hope amid the problem. As we discussed in Chapter 1, therapy is about ‘the self’ of the client. It is the self that is experiencing challenges and this experience of self or ‘sense of self’ impacts who the client is in the world – their identity. It is important for the therapist to attend to the client’s ‘sense of self’ and self-definition especially as it relates to the problem. From this the therapist can construct an initial hypothesis of the problem issue. As we value collaboration, the initial hypothesis is shared with the client and jointly constructed. From this understanding the client can solidify their goals for therapy. Following hypothesis generation and goal clarification, the task is to work on what the client is experiencing in more detail and what has led to and is perpetuating the problem. We use the term ‘play’ here to capture the multifaceted challenge of staying connected to the problem experience, of imagining new possibilities and gaining deeper insight (O’Hara, 2016). There is not enough space to really develop the significance of play in therapy, but we recommend the text by Russell Meares (2005) entitled the ‘Metaphor of Play’ as a wonderful exploration of what play means in the context of therapy. As insight and understanding are gained, further actions are likely required to address the problem issues. There are many possible actions that may be necessary to meet the problem. Areas common to working with life challenges are identified including different types of blockages, identifying pathways towards resolution, psychoeducation and acceptance. Assuming that good progress has now been made, the last stage is to review progress.

To fully appreciate each of the Practice Frameworks listed above we would need to explore in greater depth what informs them and what each stage entails in more detail. The aim here is to provide examples of different approaches. Each therapist has some form of personal framework for therapy whether they are fully conscious of it or not. The more you practise therapy and reflect on your professional experiences you will develop and adjust and hopefully become highly conscious of how you practise.

In this chapter we have sought to show how therapists integrate into their practice a wealth of knowledge about the human condition and about psychological theories of change. Some of the approaches discussed are more formalised, as in the transtheoretical approach, while others are more idiosyncratic. We have highlighted that even when we know our preferred theories we still need to consider our map of therapy or practice framework. Just as human beings are complex, therapy is a complex and dynamic process. As you learn more and practise the art and science of therapy you will continually adjust your approach.

Activity

References

Boswell, J. F., Castonguay, L. G., & Pincus, A. L. (2009). Trainee theoretical orientation: Profiles and potential predictors. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 19(3), 291-312. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017068

Cooper, M., & McLeod, J. (2011). Person-centered therapy: A pluralistic perspective. Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies, 10(3), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2011.599517

Cooper, M., & McLeod, J. (2011). Pluralistic counselling and psychotherapy. SAGE Publications.

Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., Weitz, E., Andersson, G., Hollon, S. D., van Straten, A., & Ebert, D. D. (2014). The effects of psychotherapies for major depression in adults on remission, recovery and improvement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 159(20), 118-126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.026

Derrida, J. (1974). Of grammatology (G. C. Spivak, Trans.). Johns Hopkins University Press. (Original work published 1967)

Egan, G. (2013). The skilled helper: A problem-management and opportunity-development approach to helping (10th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Grencavage, L. M., & Norcross, J. C. (1990). Where are the commonalities among the therapeutic common factors? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 21(5), 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.21.5.372

Holtforth, M. G., & Grawe, K. (2002). Bern Inventory of Treatment Goals: Part 1. Development and first application of a taxonomy of treatment goal themes. Psychotherapy Research, 12(1), 79-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/713869618

Ivey, A. E., Ivey, M. B., & Zalaquett, C. P. (2016). Intentional interviewing and counseling: Facilitating client development in a multicultural society (9th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Lambert, Michael J (1992). Psychotherapy outcome research: implications for integrative and eclectic therapists. In J. C. Norcross, & M. R. Goldfried (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy integration pp. 94–129. Basic Books.

Lazarus, A. A. (1981). The practice of multimodal therapy: Systematic, comprehensive, and effective psychotherapy. McGraw-Hill.

Leibert, T. W. (2011). The Dimensions of Common Factors in Counseling. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 33(2), 127-138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-011-9115-7

McLennan, G. (1995). Pluralism. University of Minnesota Press.

Meares, R. (2005). The metaphor of play: Origin and breakdown of personal being (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203015810

Messer, S. B. (1992). A critical examination of belief structures in integrative and eclectic psychotherapy. In J. C. Norcross & M. R. Goldfried (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy integration (pp. 130-165). Basic Books.

Messer, S. B. (2001). Introduction to the special issue on assimilative integration. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 11(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026619423048

Norcross, J. C. (Ed.). (2019). Psychotherapy relationships that work: Volume 1: Evidence-based therapist contributions (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Norcross, J. C., & Goldfried, M. R. (2005). The future of psychotherapy integration: A roundtable. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 15(4), 392-410. https://doi.org/10.1037/1053-0479.15.4.392

Norcross, J. C., & Newman, C. F. (1992). Psychotherapy integration: Setting the context. In J. C. Norcross & M. R. Goldfried (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy integration (pp. 3–45). Basic Books.

O’Hara, D. & Schofield, M. J. (2008). Personal approaches to psychotherapy integration. Counselling & Psychotherapy Research, 8(1), 53-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140801889113

O’Hara, D. (2013). Hope in counselling and psychotherapy. SAGE Publications.

O’Hara, D. (2016). The self: Reflective, relational, and embodied. Psychotherapy and Counselling Journal of Australia, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.59158/001c.71166

O’Hara, D. J., & O’Hara, F. (2020). A metatheoretical framework for the integration of the common factors of psychotherapy. In K. Andrews, F. A. Papps, V. Mancini, L. Clarkson, K. Nicholson Perry, G. Senior, & E. Brymer (Eds.), Innovations in a changing world pp. 247-258). Australian College of Applied Psychology.

Parker, Z. J., Waller, G., Gonzalez-Salas Duhne, P., & Dawson, J. (2018). The role of exposure in treatment of anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy, 18(1), 111-141. https://www.ijpsy.com/volumen18/num1/486/the-role-of-exposure-in-treatment-of-anxiety-EN.pdf

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390-395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390

Rescher, N. (1993). Pluralism: Against the demand for consensus. Clarendon Press.

Stark, M. (2021). Understanding life backward but living life forward. International Psychotherapy Institute. https://www.freepsychotherapybooks.org/ebook/understanding-life-backward-but-living-life-forward/

Zilcha-Mano, S., Roose, S. P., Brown, P. J., & Rutherford, B. R. (2019). Not just nonspecific factors: The roles of alliance and expectancy in treatment, and their neurobiological underpinnings. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00293