5 Existential and Gestalt Theory: Making Contact and Joining

Jim Schirmer

“In what is called ‘individual psychotherapy’, two people meet and talk to each other with the intention and hope that one will learn to live more fruitfully.” (Lomas, 1993, p. 5)

Key Takeaways

- Existential and gestalt therapy helped to evolve our understanding of therapy through paying particular attention to how our self of self is in an ever-unfolding process of emerging in response to the experiences we have.

- This understanding leads to some important ideas to be integrated into the practice of therapy, including: (a) demonstrating a high regard for the client; (b) seeing therapy as a relationship between ‘fellow travellers’; (c) the importance of subjective experience; and (d) attending to the here-and-now process of therapy.

- Practically, these ideas help to inform counsellors through stressing the importance of making contact and joining the client, especially in the crucial first session of counselling.

- In order to make contact and join with the client, counsellors need to develop skills such as: (a) attending behaviour; (b) observing and communicating content and experience; and (c) observing and communicating observations of process.

Introduction

In the previous chapter, you were introduced to the ideas of the pre-eminent humanistic theory of psychotherapy (person-centred therapy), and the legacy that this theory left to the practice of counselling and psychotherapy. This legacy includes a notion of a potential-seeking self, the impact of the relational conditions of the person’s journey to actualise, and the importance of the relational environment of therapy. The foundational interpersonal micro skills introduced help to establish the type of relational climate within which the client is most likely to grow towards their potential.

This chapter will build on this essential foundation and add layers of ideas and skills to integrate into the therapeutic process. Specifically, this chapter will consider two more major theories of therapy – existential and gestalt psychotherapy – and consider the contribution these theories made to modern counselling and psychotherapy. These legacies include:

- the regard for the person of the client

- therapy as a relationship between ‘fellow travellers’

- the importance of subjective experience

- the value of the process (and not just the content) of the interaction.

This chapter will apply these ideas through introducing you to the processes and skills that you need for the important first session with a client. The chapter will discuss the aim of this session as ‘making contact’, which involves building trust through processes of presence, attunement and resonance (Siegel, 2010). To meet this aim, you will be introduced to important processes involved in joining the client (e.g. welcoming the other, clarifying hopes and expectations, inviting dialogue), and the skills of attending, observing process, and reflecting content and experience, which are crucial for that session.

Theoretical Foundations

The word ‘psychotherapy’ is derived from two Greek words: therapia, meaning ‘healing’, and psyche. The word psyche is more difficult to translate, but broadly speaking is used to describe that invisible life-force that animates the body of a living thing. As such, it is variously translated ‘breath’, ‘soul’, ‘life’, ‘mind’ and ‘self’.

Consequently, anyone who is a practitioner of this process of healing the mind/soul/self (i.e. a psychotherapist) will to some degree need to ask themselves a question like ‘What is the self?’ This is, of course, the type of question that defies simple answers, and great individuals and traditions of thought have offered a variety of profound responses.

Still, at the risk of over-simplification, one major contrast in ways of thinking about self surrounds whether the self is fixed or the self is in flux. For someone who sees the self as fixed, there is a ‘true self’ or ‘real self’ that is essential to who the person ‘really’ is. In contrast, a person who sees the self as in flux regards the self (who the person is) as an emerging synthesis between the person and their experiences over time. In this latter conceptualisation, the self is depicted as being like a river. That is, while there is a continuity, regularity and recognisability to the river, it is also constantly flowing and changing. Thus (as the saying goes), you never step into the same river twice, for the river has changed in the meantime.

The following discussion examines two theories that see the self as emergent – an ever-unfolding, constantly flowing process of becoming.

Key Ideas of Existential Psychotherapy

Paul Gilbert, the founder of compassion-focused therapy, is quoted as saying, “You are living a life that is not of your choosing.” This sentence succinctly encapsulates the cornerstone idea of existential philosophy and (by extension) existential psychotherapy. The idea is that the existence that you are experiencing was not chosen; you did not choose to exist, and neither did you choose the nature of your existence. Yet here you are. Against all probability, you exist.

Moreover, as a highly conscious being, you also have the ability to be aware of and to reflect on your existence and your experience of it. In particular, you have to contend with those parts of experience that cause you discomfort, pain, and angst. In classic existential theory, these include things like the inevitability of death, the lack of inherent meaning in the world, the experience of separateness and isolation, and living with the responsibility of exercising freedom and choice (Yalom, 1980).

What existential therapy posits is that whenever someone is coming to therapy, at some level they are confronting the nature of their existence. That is, within any story that you hear as a counsellor or therapist, there will likely be threads to that story that represent themes of meaninglessness, loss, finitude, guilt (for choices made or not made), loneliness, demoralisation, powerlessness, or even just some encounter with destiny, fate or luck. For example, a client who is dissatisfied with their relationship might at one level also be reflecting on their finite existence and stressing about the limitations of staying with one person their whole life. Or a client with a crippling fear of public speaking might in part be reacting to the possibility of rejection by others as a life-or-death scenario, and thus an existential threat.

As you can see, existential therapy does not locate the problem in the person that comes to therapy. Rather, it sees the suffering of people as emerging from their experience of wrestling with the realities of their existence. However, the theory and the therapy are not fatalistic: people are not just doomed to suffer. Rather, therapy in the existential tradition aims to help people to live more courageously, honestly, meaningfully and skilfully, even in the face of the unavoidable challenges and suffering of life. Van Deurzen (2002), puts it like this:

“Assisting people in the process of living with greater expertise and ease is the goal of existential work. Learning to face the inevitable problems, difficulties, upsets, disappointments and crises of existence with confidence is what it is all about. Discovering endless sources of enjoyment and wonder in the process is the usual by-product of this venture” (p. 19).

In summary, while existential therapy sees our problems as emerging from living a life that is not of our choosing, it also sees our hope in choosing to live our life according to what is personally meaningful, even in the face of that which we cannot control.

Key Ideas of Gestalt Therapy

If someone walked up to you right this instant and asked you what you were doing, you would most likely reply, “I am reading”. If fate would have it that the person who asked you the question was a gestalt theorist, they then might have a few follow up questions:

- What is it like to read? You have used a single word to sum up a very complex activity. If you had to explain reading without using the word ‘reading’, how would you go about doing it?

- What else were you doing besides reading? There were no doubt other things going on. You were respirating, you were sitting (or standing, or walking, or lying down), you may have been thinking, you may have been daydreaming. How come, when you were asked what you were doing, you pushed all of those things into the background?

- When you think about your experience of reading, how much of your experience are you really in contact with? What parts of yourself and your environment might you have lost touch with during this experience?

As unusual as these questions might seem, they are all concerned with a matter of interest for psychotherapy, namely how we relate to the realities we experience. A starting point of gestalt theory is the observation that most phenomena we encounter are complex wholes made up of many parts. To use our example, the activity of reading is not a singular thing, but rather a complex, multifaceted experience.

While this is true, the theory would also observe that most of us do not engage with the events, activities and experiences of our lives in this way. Put bluntly, we tend to prefer simplicity to complexity. Due to this preference, we tend to do one of two things. The first thing we do is assess our understanding of something as total or complete. When we do this, we stop relating to it as it is with all of its parts and complexities, and instead just relate from our (over)simplified lens. Alternatively, we might assess our understanding of something as incomplete and subsequently only relate to it as ‘unfinished business’.

In either case, the result is the same: we end up out of contact with our own experiences. In this way gestalt therapy explains that the reason behind distress that brings a person to therapy is that the individual is out of contact with a part of themselves, an important part of a relationship, or with an aspect of their experiencing. What the individual will present, therefore, is that they have placed some parts of their experience into the foreground, while other parts of their experiences have been pushed out of awareness.

Therapy in the gestalt tradition aims to bring people back into contact with parts of themselves, their relationships and their environment that are outside of their awareness and attention. The experience of therapy, then, is to help people get an experience of being in contact with the present moment, and through this experience to start to engage more fully with other parts of their life.

[The aim is to] provide a means for interrupting the flow of self-talk, inviting us to return to ‘now’, ‘here’, ‘the actual’, in order to be more ‘present’. Thereby, individuals can learn to notice and capture subtle feeling states that easily go unnoticed. They register themselves as alive physical beings; sensing, moving and feeling. They are ready to engage fully with others (Parlett, 2001, p. 44).

In summary, gestalt is a therapy of experience, which seeks to help clients to encounter themselves more completely and to live more fully.

Key Principles

Existential and gestalt psychotherapy leave a legacy of ideas that can be integrated into the practice of psychotherapy.

Honouring the Person

In both existential and gestalt psychotherapy, the therapist is called on to hold a high regard for the person that they are seeing. This goes beyond a matter of basic manners or civil respect. From an existential perspective, it is recognising that the person in front of you is a unique event in the history of the universe. In other words, the theory calls on us to reflect on the sheer improbability of the life and consciousness of the person in front of us, and to treat this person with the reverence that this deserves. (As an aside, the theory would equally call on us to reflect on whether we treat ourselves with the same reverence, regard and honour.) Therefore, the theory implores the practitioner to not reduce the person to a ‘client’, but rather to always respect that this person has experiences, hopes, fears, and an inner life that is as complex as your own.

In a similar vein, gestalt therapy draws on the philosophy of Martin Buber to discuss how therapists should relate to their clients. Buber distinguishes between two types of relating. One is to relate to someone as if they were an ‘It’: an object to be observed, studied or even used. This way of treating a person as an ‘It’ is common in functional or transactional relationships, where the other person is a means to help us get to an end that we seek. The other way is to treat someone as a ‘Thou’: an independent and unique self with a subjective experience which transcends our knowledge and understanding. This way of treating someone is close to the idea of reverence discussed above.

A Relationship of Fellow Travellers

One idea that existential and gestalt therapy introduce to the practice of psychotherapy is the idea that ‘therapist’ and ‘client’ are not essentially different, but rather fellow travellers in the journey of life. In this conceptualisation of therapy, the fact that both participants in therapy equally have to confront the problems of existence leads to a great levelling of the encounter.

Consider this famous metaphor for the nature of therapy and the role of ‘client’ and ‘therapist’, here articulated by Hayes et al.:

“You and I are both kind of climbing our own mountains of life. Imagine that these mountains are across each other in a valley. Perhaps, as I climb my mountain I can look across the valley, and from my perspective, see you climbing your mountain. What I can offer to you as a therapist is that I can comment from my perspective, to give you my viewpoint from outside of your experience. It is not that you are broken; it is not that I am always skillful with my own barriers. We are both human beings climbing our mountains. There is no person who is “up,” while the other is “down.” The fact that I am on a different mountain means I have some perspective on the road you are traveling. My job is to provide that perspective in a way that helps you get where you really want to go” (2003, p. 81)

This image highlights two major insights about the therapeutic relationship. Firstly, it is a meeting between two humans who each have their own ‘mountain’ to climb. Being a therapist does not mean we are existentially better than our clients. We are still subject to all the same frailties, fears and limitations. Remaining in touch with our humanity helps to keep us humble and to continue to show honour and regard for the client.

Secondly, this metaphor also highlights the value of our role in the client’s journey. The equalisation that occurs through seeing each other as ‘fellow travellers’ does not mean that we therefore have nothing new or different to offer. Rather, it is our different viewpoint and perspective that can be so useful to the client. By describing what we see from our viewpoint, we give the client more perspective which they can then merge with their own viewpoint to decide how they want to proceed up their mountain.

The Importance of Subjective Experience

Both gestalt and existential theory place a high value on paying attention to the client’s subjective experience of their life. Some of this value comes from the theories’ common philosophical roots in phenomenology, a branch of philosophy that examines our conscious lived-experience of what happens to us. Phenomenology is distinctive because it is less concerned with the ‘reality’ of what has happened, and more interested in how we have experienced it.

These theories translate this idea into the therapeutic environment by focusing as much on the subjective lived-experience of the client as on the objective facts of the situation. For example, think about the implications of the following scenario:

Imagine that you practice psychotherapy in a town that has a large manufacturing industry. Due to changes in the economy, a factory has to be shut down, and hundreds of people are suddenly out of work.

It just so happens that one morning you have three clients in back-to-back appointments. All of them have lost their job in the factory shutdown. The first client you see is highly depressed as a result of this, talks a lot about the impact on their family, and describes the change as a tragedy. The second client is excited, discusses how unhappy and trapped he had been in the job, and describes the change as an opportunity. The final client is angry, speaks extensively about the political and economic climate, and describes the change as an injustice.

In this example, you have the same stimulus (phenomenon) of the factory shutdown, but three very different experiences of it. However, from the perspective of these theories, the therapist’s job is not to work out the ‘truth’ of whether the closure of the factory is a tragedy, an opportunity or an injustice. Rather, the therapist will look to understand the experience of the client.

A gestalt perspective would add a further dimension. Rather than see the various experiences of the clients (e.g. tragedy, opportunity, injustice) as mutually exclusive, the therapist could conceivably understand them as different dimensions of a complex whole. In other words, the factory closure has a tragic element, an element that creates opportunity, and an element of injustice. Therefore, the differences between the clients’ experiences are differences of emphasis; each client is focusing attention of one element of the reality, while pushing others into the background. As such, the therapist might look to understand both the focus and emphasis of the client, while also helping them get in touch with other elements of their experience.

Here-and-Now: The Importance of Process, not just Content

Students and new practitioners of psychotherapy often have to grapple with the complexity of the practice, especially with how much is going on in a single therapeutic conversation. Early on in careers it is quite natural to prioritise a focus on the content of the session, that is, the details of the narrative and information that the client is sharing.

While this is of course crucial, there is another major element to the session, which is often called process. Put simply, if content is what the client is saying, then process is how they are saying it. This includes a wide variety of things such as the client’s body language, tone, emotionality, the depth of reflection, and emphasis (i.e. what they are prioritising in the story). Paying attention to process is also a focus on the nature of the interpersonal interaction of the session; for example, how open or guarded the client is, what parts of themselves they are showing to the therapist and what parts they are protecting, and the strength or fragility of the therapeutic rapport.

Practically, an awareness of process will enable a therapist to include what is happening here and now as information that may be explored in therapy. One of the major writers in existential psychotherapy, Irvin Yalom, summarises the nature and the value of the here-and-now in this way:

“The here-and-now is the major source of therapeutic power, the pay dirt of therapy, the therapist’s (and hence the patient’s) best friend … The here-and-now refers to the immediate events of the therapeutic hour, to what is happening here (in this office, in this relationship, in the in-betweenness – the space between me and you), and now, in this immediate hour.” [Original emphasis] (Yalom, 2003, p. 47)

In other words, the facts and details given by the client are not the only material worth exploring in a session. Rather, aspects of how the client presents, relates and communicates may be significant for the therapeutic endeavour. For instance, if a client that has been talking freely suddenly falls silent, or if there are inconsistencies between different parts of the story, or if a client’s hands suddenly clench into fists when talking about a person, or if the client only makes jokes whenever you ask about their marriage, it may be worth gently reflecting on or enquiring into these here-and-now moments. (Some information about how to practically do this will be included later in the chapter.)

Implications for Practice: Processes and Skills

The insights and ideas of these two theories help to inform the counselling practitioner in several ways. For the purpose of this chapter, however, we will focus on how these insights inform the counsellor in the first session of therapy. Research has demonstrated the importance of the first session of therapy. Specifically, the first session appears to have a crucial role in forming the therapeutic alliance, which in turn predicts future improvement in the client and improves engagement through minimising drop out from therapy (Sexton et al., 2005; Falkenström et al., 2013; Sharf et al., 2010).

This section will guide counsellors in the essentials of the first session, such as the goal of making contact, the process of joining with the client, and the skills of hearing the story.

The Goal: Making Contact

One way of framing the purpose of the first session is with the gestalt therapy idea of ‘making contact’. While this is a nuanced theoretical concept, the essence of being ‘in contact’ is to be fully present to and engaged with the experiences and environment that are happening to you right now. In this way, the aim of ‘making contact’ in therapy happens concurrently in a number of ways:

- The therapist being present to and engaged with their own experiences and states of mind;

- The therapist and the client becoming present to and engaged with one another in the therapeutic environment; and,

- The client becoming increasingly aware of their experiences and relationships and thus engaging with them more authentically.

In his book The Mindful Therapist, Daniel Siegel (2010) explores what happens on a biological and neurological level when two people are in deep contact with one another. He lists three major processes: presence, attunement and resonance. Each of these processes provide the conditions for the next. That is, presence (an awareness and openness to the possibilities of the unfolding moment) provides the condition for attunement (an attentiveness to another person with a view of connecting with their inner world). Presence and attunement in turn create the conditions for resonance (the sense of two people joining together as an interconnected ‘we’). Finally, all three of these processes (presence, attunement and resonance) create the possibility of trust – a state where a person is able to be honest and vulnerable due to the presence of a reliable and responsive other. These processes provide some broad directions on what we need to keep in mind in an initial session in order to ‘make contact’ with a client.

Making Contact through Presence

The capacity to make contact in therapy starts with presence. Obviously, the idea of being present is not just about being in the same room as the client. Most of us know the dreadful feeling of speaking with someone who is physically present but psychologically absent (through being distracted, self-absorbed, unreceptive, etc.). The presence that we want to convey as therapists is quite the opposite. We want to be attentive, engaged, receptive and open.

Much of presence is communicated through non-linguistic means. Clients sense the therapist’s attention and engagement through the therapist’s body language, posture, eye contact, responsiveness, facial expressions, vocal qualities (e.g. tone, pitch, speed of speech), and proximity. Therefore, presence is a highly sensory experience, and one that cannot be ‘faked’.

Consequently, cultivating presence begins with the therapist’s mindset. It is about finding an internal space that Siegel describes as flexible, adaptive, coherent, energised and stable. It involves the therapist monitoring their own internal state. In particular, presence is often optimised when the therapist is in their ‘zone of tolerance’ – that is, in the energised zone between closed-off, rigid disengagement (on one side) and overwhelmed, chaotic hyperarousal (on the other side).

Making Contact through Attunement

The cultivation of presence provides the conditions for attunement: the therapist’s capacity to perceive the client’s psychological and relational worlds, and to move into a harmonious synchronicity with these. Here, the images that are connected to the word ‘attunement’ are helpful. You can think of attunement as being like ‘tuning in’ to a radio station or a WiFi network: it is about getting on the same wavelength as a client so that we can effectively exchange communication signals. You can also think of attunement as like an orchestra or a band tuning their instruments together, moving closer and closer together until they are creating harmony rather than discord. Similarly, the process of attunement should move the therapist and client into a harmonious rather than discordant climate of relating and communicating.

As you can see from these images, attunement is a process. It involves the repeated cycles of communication. Egan (2018) calls this ‘turn taking’. These cycles of speaking and listening create a feedback loop where the therapist can gauge the strength of the attunement with each iteration.

Practically, this process requires both the therapist’s attention and adaptation. To attune, the therapist must be paying attention to the client’s style of communication; for example, their pace, tone, vocabulary, formality, energy and cultural norms. Through this attention, the therapist can get a sense of the client’s psychological and relational patterns. From this, the therapist can adapt their own communication style to harmonise with the client.

Making Contact through Resonance

The combination of the therapist’s presence and the process of attunement results in resonance, the feeling that two people are linked into an interconnected ‘we’. The development of resonance has two key implications for contact in therapy. Firstly, in a relationship where there is resonance, there is an openness to the mutual influence of one another. Resonance means that we are receiving the other person into our own mind through engaging with their state of mind and trying to see their point of view. Our understanding of interpersonal neurobiology (see Chapter 3) shows how this even happens at a physiological level. While this state might not be symmetrical (i.e. the two people may do this at different depths), it is mutual inasmuch as a resonant relationship will have an influence of both parties.

Secondly, resonance means that the two parties are in contact as a functional relational system. This is a dynamic and ever-evolving system, but there is enough coherence that the two parts can function together as a whole. Significantly, they can work together to pursue a particular end or purpose. Therefore, in counselling, this state of resonance is crucial to create the conditions to pursue therapeutic goals.

Trust as the Outcome of Making Contact

Siegel puts forwards that the result of the culmination of presence, attunement and resonance is a relationship that is marked by trust. By trust, he means that the relationship has facilitated the kind of conditions that enable the type of honesty, vulnerability and risk-taking that are necessary for change.

This trust is the foundational basis for what therapeutic literature commonly calls the therapeutic ‘alliance’. One of the most robust findings in psychotherapy literature is that the strength of the alliance is one of the best predictors of therapeutic outcome (Horvath et al., 2011; Falkenström et al., 2013). Given this, the counsellor’s capacity to facilitate resonance and trust through their presence and attunement is foundational for all other therapeutic work.

The Process: Joining

If the aim of the first session is to make contact – that is, to use presence and attunement to build resonance and trust – then the process that is used is one of the counsellor and the client joining together in the therapeutic endeavour.

One of the simplest definitions of counselling comes from Lomas (1993), who defined individual psychotherapy as a process where “two people meet and talk to each other with the intention and hope that one will learn to live more fruitfully” (p. 5). This quote succinctly captures one of the essential features of the process of joining, namely, that it is a process that occurs between two (or more) individuals, who must come together to form a relational system. Therefore, it is safe to assume that each individual will bring their own perspectives, goals, concerns and subjective experiences to the encounter.

This assumption has been repeatedly supported by research. In particular, there is strong evidence to affirm that (broadly speaking) the counsellor and the client approach and experience the joining process differently. A synthesis of these findings across the research (Lavik et al., 2018, p. 348) showed that counsellors generally approach the joining process concerned with:

- balancing technical interventions and interpersonal warmth

- showing a genuine desire to understand

- openly supporting client agency

- adjusting to create a sense of safety

- paying attention to body language

- providing helpful experiences during the first session.

On the other hand, clients tended to value the following in the formation of the alliance:

- meeting a competent and warm therapist

- being understood as a whole person

- feeling appreciated, tolerated, and supported

- gaining new strength and hope for the future

- overcoming initial fears and apprehension about psychotherapy (Lavik et al., 2018, p. 348).

Practically, this process of joining involves a number of important elements:

- welcoming the other

- clarifying hopes, concerns and expectations

- inviting the client to share their story.

This section will discuss each of these three processes, before exploring some common variations in the structure and form that this joining process takes.

Processes of Joining: Welcoming the Other

The idea of ‘welcoming the other’ – to encounter another person in all of their individuality and subjectivity – originates in the philosophy of Levinas, but has also been argued as being a central value in the practice of counselling (Cooper, 2009). Orange (2016) calls this an act of therapeutic hospitality, and thus the counsellor acts somewhat like a good host. That is, in welcoming the client into the therapeutic space they have multiple aims, such as:

- helping the person feel at ease;

- orientating them to the space and helping them feel comfortable and safe; and

- showing respect and honour to the person and their needs.

Consequently, the counsellor is critically aware of the importance of these early moments of these relationships and the power of first impressions. In welcoming the client, the counsellor is attentive to small details in how they greet the client and introduce themselves, appearing prepared, professional and unhurried, and being able to readily connect with the client over small talk.

How welcome the client feels can even be influenced by how they have experienced the practice before they meet the counsellor. This includes factors like the website, the process of booking the session, the ease of access to the session (whether that’s the location or the technology if the session is via telehealth), and the nature of the space in which therapy takes place.

In summary, in effectively welcoming your client, you can ask yourself two questions:

- What might be happening that could lead the client to feel less safe?

- What might I do to help the client feel more safe?

Processes of Joining: Clarifying Hopes, Concerns and Expectations

A distinctive part of the joining process is the exploration of the client’s hopes, concerns and expectations. Each of these three areas has implications for the counsellor’s goal of making contact with the client and forming an alliance of resonance and trust. Firstly, understanding the client’s hopes enable the counsellor to find the major point of connection. In other words, the hopes are the client’s energy for engaging in this therapeutic endeavour, and the counsellor wants to join onto these as an ally for this endeavour (O’Hara, 2013).

Equally, understanding the client’s concern (or questions) about the process of therapy is crucial to the joining process. These concerns present potential barriers to the joining process, and having the chance to address these directly creates the possibility of overcoming these early. Finally, understanding the client’s expectations about how therapy will run and how change will occur is vital to the joining process. Unclarified expectations carry the potential of causing discord rather than resonance, as the client and the counsellor approach the process in different ways.

Processes of Joining: The Invitation

At some point in the process, the counsellor invites the client to share their story and information about themselves. This invitation is not just a routine, utilitarian statement to get conversation going; rather, it is a moment where the counsellor can communicate their sincere desire to listen and to get to know the client. As Nelson-Jones (2008, p. 62), puts it, “permissions to talk are ‘door openers’ that give clients the message: ‘I’m interested and prepared to listen’… Helpers are there to discover information about clients and to assist clients to discover information about themselves”.

The invitation may be a simple question, such as:

What brings you in to see me today?

I’m wondering whether you would be willing to share a little bit about yourself and about what’s troubling you at the moment?

What was it that led you to make the appointment to see me?

Some practitioners might include a statement that helps to frame the invitation; for example:

There would no doubt be a lot on your mind, and lot for me to get to know in order to be able to find out how our time together might be useful for you. Where would you like to start?

If someone other than the client made the referral, it might be worth acknowledging that, as well as communicating that you are present to hear their story:

You were referred to see me by ________________. I was wondering whether you could share with me how you see the referral from your point of view?

Remember that the invitation serves the larger goal of making contact and joining with the client. Sometimes clients might have trouble with knowing where to start. In this case, the process of joining will likely be supported by you offering reassurance and further guidance, such as in the following examples:

Sometimes it is hard to get started.

We’ve got time; there’s no rush.

Maybe go back to the day that you made the appointment. What was on your mind that day?

On the referral it said you have been dealing with ________________. Can you start by telling me a little more about that?

Practical Variations in Joining Processes

In practice, you may come across some key variations in how the first session is run. From practice to practice and from professional to professional, you will witness a spectrum of different approaches. One spectrum where you may see variation is the difference between a structured and an unstructured first session. A highly structured first session usually involves a series of prepared topics and questions to guide the information and flow of the session (for example, an intake interview). In contrast, an unstructured first session will allow the conversation to flow naturally and for a direction to emerge organically through the discourse.

Another spectrum that can commonly be seen in practice is the variation between client-led and practitioner-led sessions. The variation centres on who takes responsibility for the direction and order of the session. Individual practitioners generally have a preference for which way they would like to operate, but often have to also adapt to each client’s expectations and communication style.

Each variation has its own strengths and limitations, and practitioners and agencies can at times be found to rigorously defend their preferences. For the purposes of your own development, it is sufficient to know that these variations exist and to come to discover your own preferred way of being, while also being responsive to the requirements of your practice context.

The Skills: Hearing the Story

In pursuing the goal of making contact through the process of joining, there is a range of key skills that counsellors regularly employ. This section will introduce you to the skills of:

- attending behaviour

- observing and reflecting content

- observing and reflecting experience

- observing and communicating process.

Skills: Attending Behaviour

As is widely acknowledged, only a small fraction of our communication occurs using words. We are constantly reading messages from things like bodily posture, gesture and behaviour, facial expressions (especially eye movement and behaviour), vocal qualities (volume, pitch, emphasis, pauses, etc.), physical proximity or distance, and other physiological cues (e.g. breathing rate, changes in skin colour, smell, muscle tension, etc.) (Egan, 2018). In fact, there are so many forms of non-verbal communication that entire dictionaries have been created to document the range of things that we observe every day but rarely take into our conscious awareness (Givens & White, 2021).

For the therapeutic goal of making contact through the process of joining, counsellors use what is commonly called attending behaviour; that is, non-verbal communication that shows attention and interest in the client. In brief, this is the type of behaviour that shows undivided attention to the client. While this might vary slightly depending on the style of the therapist, this often includes things like:

- having a relaxed or composed body (i.e. not fidgeting, distracted)

- facing the client and maintaining eye contact (while being aware of threatening or invasive eye contact)

- being aware of a comfortable physical proximity (not too close or too distant; being at the same height as the client)

- communicating interest through posture (e.g. leaning towards the client)

- having facial expressions, gestures and tone of voice that are responsive to the tone of the client’s story, and also congruent with what you are expressing.

Reflection questions

Skills: Observing and Communicating Understanding of Content

Most people would know intuitively that while being present and attentive is necessary for the process of joining, it is not sufficient. Our clients need more from us than just our attention, and an essential part of that is to be heard and understood. Therefore, a further part of the joining process is the skill of observing and communicating understanding of the content of the client’s story.

The first step on this is being able to identify the key elements of what the client has said. In other words, it is your ability to listen closely enough to hear the essence of what they are saying. At times, the client might give you a particular word or phrase that summarises most of what they are trying to say. In this case, it might be sufficient to reflect this back as closely as possible to the client’s words.

In many instances, however, it will be up to the counsellor to find a way to encapsulate the key message of the story. For example, consider a client who might be saying the following:

I work four days a week, and Tuesday is my non-workday. But, believe me, it isn’t a day off. Not when you’re a mother of three kids. So, by the time I got them all to school – and my eldest is in high school, so there’s two drop offs – I’ve already been awake for a few hours. And that’s just the beginning. Washing, shopping, errands.

Last week I got the car serviced, and that was a nightmare. Took longer than expected, so I was late to pick the kids up. And then, at six o’clock, when my husband walks through the door, the first thing he says to me is, “When’s dinner?”

If the client was speaking at an average rate, they would say that in about a minute or less, which goes to show how much information can be communicated in a short space of time. As the counsellor, it is up to you to identify the message that the client is communicating. In this example, probably no single detail is the most important part of the story. Rather it is the cumulative details that suggest what the client is trying to get across: that she is busy, overworked, under constant demand.

Having observed the key message, the task of the counsellor is to communicate this back to the client. This will largely depend upon the individual counsellor, but the skill involves summarising the message in as succinct a phrase as possible. Using the previous example, the counsellor might say something like the following:

It really was just one thing after another.

It sounds like there can be no end to the demands that you have to fulfil.

So, even your one day away from work is just filled with more work.

Skills: Observing and Communicating Understanding of Experience

As is emphasised by the theories that we have studied in this chapter, understanding the content of the story is only part of the picture. Rather it is important to understand the client’s subjective, lived experience of the events that they are describing. As discussed, different people can go through the same thing and have very different experiences. For the client to feel heard, they need you to communicate that you have heard what it is like for them to live the life they are living.

As with the content, this involves both observing and communicating. One of the most important elements of lived experience is emotion – the feelings that arise in response to the events of our lives. At times clients will use explicit feeling words, which you can simply communicate back to them to show that you’ve heard.

Client: When my son talks to me like that, I get really sad.

Counsellor: Sad?

Client: Yeah, upset. After all I’ve done, he treats me like dirt.

Client: I’m just so mad at my boss. I can’t believe what she’s done now.

Counsellor: There’s a lot of anger there.

Other times, the emotion will be communicated more indirectly, and the counsellor will need to tentatively infer what the experience is like.

Client: All I asked for was one night of babysitting and Mum couldn’t even do that. After all that she does for my brothers, it seems the least I could get.

Counsellor: It sounds like this felt really unfair, maybe you’re even a bit angry. Would that be right?

If this reflection is offered in this way, at times the client might be able to clarify their experience, even if the counsellor didn’t quite get the exact emotion correct the first time. To continue the previous example:

Client: All I asked for was one night of babysitting and Mum couldn’t even do that. After all that she does for my brothers, it seems the least I could get.

Counsellor: It sounds like this felt really unfair, maybe you’re even a bit angry. Would that be right?

Client: Not angry… more just let down.

Counsellor: Yeah, is it more like disappointment than anger?

Client: Yeah, yeah. Disappointment is a good word.

Still, the client’s subjective experience is not simply limited to the emotions they feel. Other parts of their subjective experience that you need to listen for and observe include things like:

- Values and priorities – What is most important to the client? Is there anything precious to them that is being threatened by these events?

- Causes and explanations – How does the client explain what is happening to them? What is causing their experience?

- Judgements and evaluations – What categories does the client divide the world into (e.g. good/bad, painful/comfortable, etc.)? What criteria does the client use to decide if something is in one category or the other?

- Meaning and significance – Why is this important? What are the implications from the client’s point of view?

With these in mind, you will be able to offer more complex reflections of the client’s experience. Typically, this includes the client’s emotions, but also coupled with a reflection on why they feel they way they feel from their point of view. Look at the following example of how the counsellor builds a picture of the client’s experience throughout the interaction.

Client: Honestly, I still can’t believe that Dad’s gone. I mean, he was only meant to be getting minor surgery, and so when I got the call to say that he had died… it just felt so unreal.

Counsellor: It was such a shock, wasn’t it?

Client: I can’t believe he’s gone. I know this sounds strange, but I just never considered my dad dying. He’s so strong. And healthy. I mean, I can’t even remember him being sick. It was like nothing could stop him.

Counsellor: It sounds like it is almost unbelievable – unfathomable – that someone who seemed so unstoppable could be gone so suddenly.

Client: Right. You know, I probably just expected him to grow old. You know, get frail, get sick, that sort of thing. I can picture him as an old man slowly losing his strength, but I’d never thought he’d die at his age.

Counsellor: So part of the shock of all of this was that you had never expected it to happen in this way. It is not the way that things were meant to pan out.

Skills: Observing and Communicating Observations of Process

A final skillset that counsellors use through the joining process is observing and communicating process. As gestalt and existential theory would posit, this means listening to how the client is telling their story, and not just what they are saying. It means paying attention to the here-and-now process occurring in therapy, and (if appropriate) reflecting on what messages this might be communicating.

Some of the things that you might pay attention to in observing process include:

- the client’s body language, non-verbal communication, mannerisms, and gestures

- the way the client structures their story, such as what material they prioritise, the sequence in which they put events, and words or expressions that are used more than others

- any discrepancies or omissions, such as an inconsistency between the content of the story and the client’s affect, or a reaction or consideration that might be expected but is not present

- how the client interacts interpersonally (this will be covered in more detail in Chapter 6).

At times, the here-and-now process will be able to be observed, but sometimes it might be that the counsellor will want to ask about it directly:

You’ve been talking a lot today about a very distressing part of your history. I am just wondering what that’s been like for you to do this, and how you are feeling here and now having told this story?

There’s no doubt that this whole experience has left you very stressed. Can you pinpoint anywhere in your body where you are feeling or sensing that anger right now?

In observing and communicating process, it is important to be clear about what you do know and what you don’t know. What you do know is what you have observed. What you don’t know is what it means. Therefore, in communicating your observation of process, it is best to focus on the observation and allow the client to fill in the interpretation. The most obvious way to do this is to couple the observation with an invitation for the client to explain it; for example:

I notice that you keep looking at your watch. Is there something on your mind that would be useful for me to know about?

[Client goes silent] I’m just wondering what is going on for you at the moment?

Just now, as you’ve started to talk about the work you do, I’ve felt your energy lift and seen a smile on your face for the first time this hour. Can you tell me what that’s about?

Another way to do this is to make the observation and offer a range of possible explanations, leaving it open for the client to explain this for you.

It seems that every time we start to talk about your relationship you start to rub your eyes and your brow. Are you thinking about something, or is this something that is difficult to talk about, or something else?

Conclusion

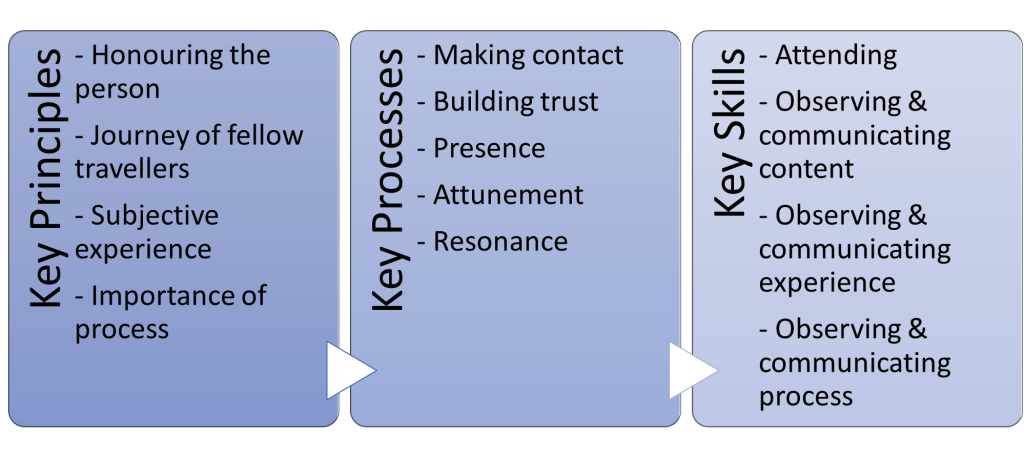

This chapter has introduced the importance of the first session of counselling. Using the theoretical foundations of gestalt and existential psychotherapy, this chapter has provided an overview of some of the key principles, processes and skills that are provide a foundational for effective practice in counselling and psychotherapy. These are summarised in the figure below:

Figure 1. Key Principles, Processes and Skills for Effective Practice in Counselling and Psychotherapy

Given the centrality of the first session of counselling, understanding these principles and mastering these processes and skills represent a key priority – perhaps even the highest priority – for new practitioners. The more time you can spend in deliberate practice activities of trying, reflecting, getting feedback and trying again, the better. That said, the mastery of these skills also represents the work of a lifetime.

Questions for Reflection

Additional Reading

The following books are some of the most thorough introductions to the foundational skills of counselling and psychotherapy, and are thus a great reference to get in depth information on how to practise the skills:

Egan, G.D. (2018). The skilled helper: A problem-management and opportunity-development approach to helping. Cengage.

Ivey, A.E., Ivey, M.B., & Zalaquett, C.P. (2022). Intentional interviewing and counseling: Facilitating client development in a multicultural society (10th ed.). Cengage.

References

Cooper, M. (2009). Welcoming the other: Actualising the humanistic ethic at the core of counselling psychology practice. Counselling Psychology Review, 24 (3/4). https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/29135/

Egan, G. D. (2018). The skilled helper: A problem-management and opportunity-development approach to helping. Cengage.

Falkenström, F., Granström, F., & Holmqvist, R. (2013). Therapeutic alliance predicts symptomatic improvement session by session. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 317–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032258

Givens, D. B., & White, J. (2021). The Routledge dictionary of nonverbal communication. Routledge.

Hayes, S. C., Masuda, A., & De Mey, H. (2003). Acceptance and commitment therapy and the third wave of behavior therapy. Gedragstherapie (Dutch Journal of Behavior Therapy), 2, 69-96.

Horvath, A.O., Del Re, A., Fluckiger, C., & Symonds, D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 9-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0022186

Lavik, K. O., Frøysa, H., Brattebø, K. F., McLeod, J., & Moltu, C. (2018). The first sessions of psychotherapy: A qualitative meta-analysis of alliance formation processes. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 28(3), 348-366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/int0000101.supp

Lomas, P. (1993). The psychotherapy of everyday life. Transaction Publishers.

Nelson-Jones, R. (2008). Basic counselling skills: A helper’s manual (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

O’Hara, D. (2013). Hope in counselling and psychotherapy. Sage Publications.

Orange, D. (2016). Nourishing the inner life of clinicians and humanitarians: The ethical turn in psychoanalysis. Routledge.

Parlett, M. (2001). On being present at one’s own life (Gestalt Psychotherapy). In E. Spinelli & S. Marshall (Eds.), Embodied theories (pp. 43-64). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446218013

Sharf, J., Primavera, L. H., & Diener, M. J. (2010). Dropout and therapeutic alliance: a meta-analysis of adult individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, research, practice, training, 47(4), 637-645. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021175

Sexton, H., Littauer, H., Sexton, A., & Tømmerås, E. (2005) Building an alliance: Early therapy process and the client–therapist connection. Psychotherapy Research, 15(1-2), 103-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300512331327083

Siegel, D. J. (2010). The mindful therapist: A clinician’s guide to mindsight and neural integration. WW Norton & Company.

Van Deurzen, E. (2002). Existential counselling and psychotherapy in practice (2nd ed.). Sage.

Yalom, I.D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books.

Yalom, I.D. (2003). The gift of therapy: An open letter to a new generation of therapists and their patients (Revised ed.). Piatkus.