4 Person-Centred Therapy

Denis O'Hara

“The good life is a process, not a state of being. It is a direction, not a destination.” – Carl Rogers

Key Takeaways

- Person-centred therapy is based on strong phenomenological foundations as are other humanistically informed approaches. Phenomenology highlights the importance of paying attention to experiencing in-the-moment.

- Carl Rogers privileged the idea of the self-actualising process believing that human beings have a profound capacity for orientating their life towards wellbeing if they are supported by a facilitative environment.

- A person’s self-concept is influenced by their internal experience of self and especially their experience of self within relationships. The real or genuine self seeks to continue growth and development throughout life, and this is facilitated, in part, by envisaging the ideal self.

- It is essential that therapists have both an empathic ‘way of being’ with clients and effective skills of communication.

Introduction

Humanistic theory of counselling and psychotherapy incorporates several substantial theories that share common philosophical assumptions and practice principles. While the term ‘humanistic’ captures many fundamental dimensions of these theories, it can also be a term that adds confusion. When we speak of humanistic theory, we are not referring principally to humanistic philosophy, although there is a strong link between humanistic philosophy and humanistic psychological theories. Our aim here is not to delve into humanistic philosophy, rather to explore one of the earliest and most prominent of the humanistic theories of counselling and psychotherapy, Person-centred Therapy.

By the 1940s, the dominant theories of psychotherapy were analytic in nature with the most dominant of these being Freud’s psychoanalysis. Other derivatives of psychoanalysis included such approaches as Jungian theory, Adlerian individual psychology, and the ego psychology of Erikson. All these theories were based, in part, on the influence of the unconscious on human behaviour, and by various means sought to free people of unhelpful confusions about the self, brought about by harmful relational experiences. A fundamental assumption in these approaches was that unless insight was gained into past experiences, identity, and relational deficits, then the unconscious material would unduly affect functioning in the present. In other words, human behaviour was to some degree determined by the unconscious.

By the 1940s Carl Rogers lead a major directional turn in psychology by promoting the importance of human self-determination. While Rogers did not reject the idea that the unconscious influenced human behaviour, he disagreed with earlier theorists that human beings were largely determined by the unconscious. Consistent with humanistic philosophy, Rogers believed that human beings had much more power of self-determination than many thought and that free will and choice were fundamental to health and wellbeing. Like Maslow, Rogers agreed that if the hierarchy of human needs could be met, then the individual would naturally orientate themselves towards self-actualisation.

A key influence in Rogers’ thinking, apart from humanistic philosophy, was the emerging science of phenomenology. Thinkers like Hursserl (1931) and Heidegger (1959) highlighted the importance of experience and consciousness. One of the central foci of phenomenology is attending to experience in the here-and-now for the purpose of becoming intimately aware of one’s existence. In everyday life we can have some awareness of our experiences without really reflecting on them. In phenomenology, the aim is to become aware of the essential nature of experience. In other words, as we are more able to attend to ourselves, that is, our experience of being in the world, we become more conscious. In phenomenology this is referred to as the ‘phenomenological attitude’ and it appealed to Rogers as he saw its potential to inform psychotherapy.

However, Rogers recognised that while human beings had the capacity to become more conscious in life, this often did not occur or did so to a limited degree. In other words, the organismic process, of paying attention to self and experience for the purpose of moving in the direction of self-actualisation, was often blocked or attenuated. Rogers believed that such blockages originated in the individual’s experience of self in relationship to others. He argued that instead of seeing ourselves as naturally worthy and good, we experienced ourselves as being evaluated based on our performance, what Rogers referred to as conditions of worth. Whether we were being actively evaluated by others or not, the issue is we experience ourselves as being evaluated and found wanting. This negative self-evaluation may have arisen from a negative word from parents or carers, teachers, friends or others. Rogers believed that when we experience our self-worth as conditional it affects our self-concept resulting in blocks to ongoing self-actualising.

A child’s formative years are seen as highly influential in internalising values and in developing self-concept. This is different from the psychodynamic idea that we internalise the experiences and conceptualisation of specific others like parents and caregivers. Both approaches refer to introjection of primary life experiences, but the person-centred view highlights the development of more generic values and conceptions of the self. Within the framework of the self-actualising process, self-concept is understood by Rogers to be paired with an ideal self-concept. This is the self that one is desirous of becoming. The present or ‘real self’ is often compared to the ‘ideal self’ with the hope that notions of the ideal self will act as motivation for further self-actualisation.

One of the challenges in moving towards self-actualisation is the existence of a confused or inaccurate self-concept brought about by conditions of worth internalised from one’s developmental experiences. One of Roger’s great innovations was the identification of key blockages or restraints on this self-actualising process. All things being equal, if blockages to the self-actualising process are removed, then the person would naturally realign their growth trajectory. Based on this logic, Rogers reasoned that if supportive conditions were provided, the individual would gain increased conscious awareness and begin to move in a self-affirming direction. To this end, he identified six fundamental conditions that must be present for an individual to feel supported and to re-engage in what he called their organismic valuing process. These six conditions are:

- That two persons are in [psychological] contact

- That the first person, whom we shall term the client, is in a state of incongruence, being vulnerable and anxious.

- That the second person, whom we shall call term the therapist, is congruent in the relationship.

- The therapist is experiencing unconditional positive regard toward the client.

- That the therapist is experiencing an empathetic understanding of the client’s internal frame of reference.

- That the client perceives, at least to a minimal degree, conditions 4, and 5, the unconditional regard of the therapist for him, and the empathic understanding of the therapist (Rogers, 1957, p. 96).

Emotions, Motivation and Incongruence

Human beings are relational beings and as such it could be said that an individual does not exist outside of relationship. It is certainly true that the human infant cannot exist without the support of others. More fundamentally though, human beings have a deep need to see themselves in the eyes of others. It is this relational connection that frames the nature and process of the emerging self of the child. Humanistic theory is sometimes called organismic theory because it focuses on the growth and development of the organism. A plant, animal or human being moves through various phases of growth nurtured by its environment. As noted above, limitations in this environment can stunt growth just as facilitative conditions can support growth. Humanistic theory posits that human beings are naturally oriented towards growth and development. In person-centred theory this natural motivation towards growth is supported by our inner experiences, especially our emotions. According to Sanders and Hill (2014), our emotions contribute to motivation in several ways. Emotions are involved in:

- the origination and production of needs and wishes which push behaviour

- the intensity of needs and wishes, determine the strength and resilience of the behaviour (Sanders & Hill, 2014, p. 76).

The centrality of emotions and feelings within Rogerian thought is well acknowledged although the distinction between emotions and feelings is less clearly delineated. Rogers understood emotions as referring to the physiological functions underpinning feelings, and feelings were more the symbolised experience of having an emotion (Stiles & Horvath, 2017). Personal change occurs when we are able to be present to our experience, especially in the form of feelings and in doing so symbolise them or integrate them into our awareness in new ways. This organismic perspective reflects a deep appreciation for meaning linked to the whole of a person, rather than it being principally linked to cognitive abstraction. With this understanding Rogers sought to join with the experience of the client in a deeply empathetic way so that he could more accurately reflect back to the client their own experience, thus providing them with the opportunity to symbolise it and therefore move the experience from an unreflected state to reflective awareness. The importance of joining deeply with the organismic experience of the other is well highlighted by Rogers in the following statement:

Another question I ask myself is: Can I let myself enter fully into the world of his feelings and personal meanings and see these as he does? Can I step into his private world so completely that I lose all desire to evaluate or judge it? Can I enter it so sensitively that I can move about in it freely, without trampling on meanings which are precious to him? Can I sense it so accurately that I can catch not only the meanings of his experience which are obvious to him, but those meanings which are only implicit, which he sees only dimly or as confusion? (Rogers, 2011, p. 87).

We see in this quote both Rogers’ emphasis on maintaining an unconditional regard for the other and also the importance of being deeply empathically available. What is also implicit in this statement is how psychological change is a process of experiencing an incongruence between experience and awareness. As an individual becomes aware of their experience, their feelings and interoceptions, it is more likely that they will notice the inner incongruence. This direct experience of personal incongruence makes possible the re-making of meaning, of realigning the organism with the valuing process. Rogers (2011) expressed this process of change by stating, “The incongruence of experience and awareness is vividly experienced as it disappears into congruence” (p. 217). A contemporary of Rogers famous for developing Focusing therapy, Eugene Gendlin, captured essentially the same organismic view of the change process by stating that in change we move from felt sense to felt meaning (Gendlin, 1969).

While all six conditions of change need to be present to facilitate the therapeutic change process, the three conditions of unconditional positive regard, empathy, and genuineness or congruence are most often highlighted as the sine qua non of person-centred therapy. While each of these conditions sound logical and straightforward in principle, the provision of these conditions is quite challenging for the therapist to provide.

Unconditional Positive Regard

The notion of positive regard for the client sounds in many ways to be self-evident if therapy is to progress well. While this may be true, it is not always as easy as it may sound. This is because people come to see therapists with a wide variety of problems, personalities, cultural backgrounds, worldviews and life experiences, to name a few points of diversity. While much of what is presented in therapy is common to human experience, how people identify, organise, prioritise and express their values can differ significantly. It is not possible for therapists to feel a natural affinity for all their clients yet the need to offer positive regard is seen as essential. Notably, recent neuroscientific research has acknowledged that at some level whether conscious or otherwise, people can read the subtle nonverbal-cues of another. The discovery of mirror neurones is a good example of how human relating is communicated on multiple levels (Penagos-Corzo et al., 2022; Rasmussen & Bliss, 2014).

The provision of unconditional positive regard, empathy, and congruence provide an environment in which previous conditions of worth are less likely to influence the client. In other words, a genuinely supportive environment in which the person is able to attend to their deep experiencing in-the-moment will likely free them to become aware of the incongruence between the real and ideal self and reorientate them towards self-actualisation.

Empathy

McLeod (2013, 178) noted that

“The importance attributed to empathic responding has been one of the distinguishing features of the person-centred approach to counselling. It is considered that, for the client, the experience of being ‘heard’ or understood leads to a greater capacity to explore and accept previously denied aspects of self”.

When therapists think of the person-centred approach, it is usually with the significance of empathy in mind. When Rogers first promoted this idea it was seen as novel and even unscientific. However, since then empathy has been studied in depth demonstrating that it is indeed an important part of the therapeutic relationship and therefore of the change process. One of the difficulties though in operationalising empathy is that it is somewhat difficult to define especially in terms of a distinction between a state or way of being and a skill. Some in the therapeutic community have highlighted the state of empathy and others the skills of offering empathy. Barrett-Lennard (1962), a colleague of Rogers and a notable Australian academic, highlighted the importance of the communication of the experience of empathy in a way that it is received by the client. It may be possible to be empathic but not communicate one’s empathy. Barrett-Lennard developed and researched what he referred to as the empathy cycle wherein empathy was first experienced by the therapist, then communicated in such a way that the client gained an awareness of the therapist’s deep empathic connection with them.

Congruence

Congruence is the act of being genuine both internally with oneself and interpersonally with others. While this may seem an obvious and laudable aim, it is not always easy to achieve. Obviously, clients do not want their therapists to withhold thoughts and ideas they may have about them and their presenting problem. We all want a real and genuine encounter with another, especially when there is a marked degree of vulnerability involved. However, it is not responsible of therapists to express every thought they may have about their client and their concerns. Therapists often need time to make sense of what is happening for the client, in general, and of what is happening in the room in any given moment. There is a gap between processing and communication.

It may also be challenging to maintain genuineness when the therapist disagrees with the client’s point of view or behaviours. What is it to be genuine in such circumstances? Congruence or genuineness is first about self-awareness. We have first to be aware of our own thoughts and feelings before connecting with another. We cease to be congruent in our communication when we are not in touch with ourselves. Congruence does not mean we are obliged to express everything we think or feel, but it does require of us to be real in the therapeutic encounter. It is true that people will often sense if another is being real and genuine. Congruence produces a feeling of deep connection as sense of ‘we are in this together’. When this feeling is present, the process of therapy is clearly underway.

The Therapeutic Process

Given the key principles of person-centred therapy, what does the therapeutic process look like? Rogers was very helpful here in delineating seven stages of the therapeutic process. He emphasised though that the process was not limited to seven stages because everyone’s experiencing and accessing of their phenomenological experience varies requiring many iterative steps along the way towards increasing self-actualising.

Stage 1: Communication is only about externals. In this stage the person is not really in touch with their phenomenological experiencing and relate to their experience conceptually and behaviourally not experientially. In this stage feelings and meanings are not recognised or owned.

Stage 2: Expression begins to flow in non-self topics. As the person realises they are being heard and valued in therapy, they begin to relax a little and start to share about a range of topics descriptively but not linked clearly to feelings. Problems are still seen as being external to the self.

Stage 3: A further freeing of expression including about self as object. As the experience of therapy increases to be positive a further freeing of expression is evidenced. Included in this expression now is stories that include the self as the object of focus but not clearly linked to the feelings of the self. The closest the client may come to identifying feelings is the feelings of others about them or past feelings they may have had but not present feelings.

Stage 4: Feelings are now described although as objects in the present. The safety of therapy now allows the client to begin to refer more directly to feelings and experiences but still with some concern or even surprise that they are ‘showing up’. There is not yet quite the readiness to explore these feelings and related meanings.

Stage 5: Feelings are expressed in the present. “Feelings are very close to being fully experienced” (Rogers, 1961, p. 203). There is now an increasing ownership of feelings.

Stage 6: An inner flow and linking of feeling With experience and meaning is now experienced. The immediacy of experience is allowed and directly experienced and accepted.

Stage 7: Feelings are fully experienced and trusted and act as referents to past and present meaning. The person now is able to be fully present to their experience and is able to work with moments of ‘felt sense’. Felt sense being deeply appreciated leads to felt meaning and free expression of the self.

Eugine Gendlin and Focusing

Gendlin was an important contributor to humanistic therapy and especially to person-centred therapy. As noted earlier, he developed an approach to therapy called ‘focusing’. Like person-centred therapy, focusing therapy is based on phenomenology and the centrality of experiencing. Gendlin highlighted the principal need in the ‘phenomenology of the moment’ of attending to the ‘felt sense’. Gendlin was a philosopher and therapists and believed that the ‘felt sense’ was more than recognition of emotion or feelings but went beyond feelings to a deeper inner sense of the whole person especially via the somatic. He believed that within the body and within deep attention to experiencing we could access more of what the body knew or more accurately what the organism knew of itself. Gendlin’s ideas were complementary to Rogers’ and as such the importance of attending to the felt sense was shared by both psychotherapy pioneers. Gendlin outlined six steps in the focusing process in which one might gain access to felt sense and move towards increasing felt meaning.

Step 1. Clearing the space. The first priority in this step is to relax and begin to pay attention to inner experience, to feelings and the body.

Step 2: Felt sense. Begin to focus on a particular problem but without analysing it simply paying attention to what being aware of the problem elicits inside of you.

Step 3: Handle. Focus on the quality of this unclear felt sense? Allow a word, a phrase, or an image come up from the felt sense itself. Stay with the quality of the felt sense till something comes into awareness.

Step 4: Resonating. At this point the idea is to connect the felt sense with a word, phrase or image.

Step 5: Asking. Now one asks the felt sense, word or phrase (tentative meaning) to help reveal what the problem is about or connected to or moving towards. Be aware of potential shifts in feeling and meaning.

Step 6: Receiving. Receive whatever comes with a shift in an open relaxed manner. Pay attention to any shifts or personal release, even if only small (Gendlin, 2007).

Visit Focusing Oriented Therapies for videos on this therapy.

Implications for Practice

Micro-skills of Communication

One of the principal qualities in Rogers’ approach to practice is what might be referred to ‘a way of being’. When viewing videos of Rogers conducting therapy it is obvious that he held a highly empathic, genuine stance towards the client. Of course, this stance reflected the idea of the ‘core conditions’ required for therapeutic change to occur. Rogers even stated at one point that these ‘core conditions’ were sufficient in and of themselves for change to take place. Without delving into the debate about whether this non-directive approach was actually sufficient for change, Rogers in his own practice certainly highlighted the importance of a particular stance or way of being that was critical to the therapeutic encounter. This view is probably best reflected in his understanding of empathy as a state of being and less a skill to master.

Watch Carl Rogers on Person-Centered Therapy (Kanopy, 1h11m, UQ login required).

One of the difficulties of appreciating and prioritising an attitude or stance towards therapy as Rogers did, was that an attitude or way of being is not so easily taught. By its nature a way of being is developed within the context of one’s personality, educational and life experiences. Therapists bring who they are to the whole therapeutic enterprise. So, while the theory of person-centred therapy could be taught, the practice of it was and is more challenging to convey.

Two researchers who were colleagues of Rogers’ at Chicago University in the days when the theory was being developed and researched, Charles Truax and Robert Carkhuff (1967), approached the problem of teaching the person-centred approach by highlighting the skills in human communication. A skills approach to connecting with clients has several benefits but also some limitations. Some of the benefits are that:

- Micro-elements of communication can be identified specifically and therefore measured

- Students can practise applying respective micro-skills and then draw them into a fluid integrated sequence of communication

- Deficits in communication skills can be remedied.

With this view in mind, Truax and Carkhuff developed an approach to teaching the essentials of person-centred therapy by focusing on micro-skills of communication. Their approach to teaching psychotherapy has had influence far beyond person-centred theory and is now commonly taught across counselling program, no-matter the primary theoretical orientation. Of course, the debate about whether therapy is primarily a set of skills or a way of being has never really gone away. In the view of the authors, being an effective therapist definitely is about the person of the therapist and their way of being but is also about having a developed set of communication skills – the two go together. If ‘being’ is disconnected from the application of skills, skills simply become technique lacking genuine relational connection.

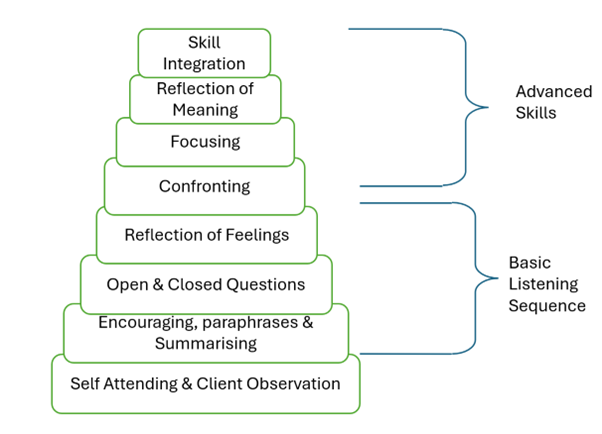

One of the most notable current proponents of the importance and benefits of micro-skills training for counsellors is the husband-and-wife team of Allan Ivey and Mary Bradford Ivey. Different editions of their text “Intentional Interviewing and Counseling” have been used in counselling programs for over thirty years. The Iveys and their associates drawing on the earlier work of Truax and Carkhuff developed a skills framework that has helped teachers and students of counselling to develop their communication skills and their capacity to develop and maintain the therapeutic relationship. The Iveys outline a hierarchy of micro-skills best illustrated in the skills pyramid below.

Figure 1. Microskills Hierarchy

Communication skills are organised into two levels: the basic listening sequence and advanced skills in which all aspects of communication are integrated. It is instructive that the first skills listed are a combination of, firstly, attending to one’s own behaviour and, secondly, to the observation of the other. It would not be inconsistent to say that the therapist should not just attend to their own behaviour but their way of being. The therapist’s presence in the room with the client is of paramount importance. Presence is much more than the skills one possesses; it is about all that the therapist is as a person including their knowledge and skills.

At first glance the list of communication microskills might appear almost mundane. Everyone knows about paraphrasing for example, at least, in principle. However, the offering of a paraphrase within the counselling context wherein it is offered accurately and in a timely manner and in a ‘certain’ way, is much harder to do than one might think. A paraphrase says to the client “I am really listening and tracking with what you are saying – I’m really interested”. Another author who highlights the importance of microskills is Gerlad Egan (Egan & Reese, 2019). Egan makes an insightful observation that a well-timed paraphrase is a form of basic empathy. This is true because when we offer a paraphrase we are intimating our interest in the client and their story.

Reflection of feelings is the next skill in the hierarchy and one of the more difficult skills to master. Reflection of feeling is often a misunderstood skill as it can be interpreted as a technical recognition that an emotion is present. For example, if a therapist conveys that they recognise that the client is experiencing some anger, it can be offered as an abstract idea or as a fellow feeling. While it is fine to acknowledge the technical presence of an emotion, it is quite different to feel the client’s emotion and in an empathic manner offering back this feeling to the client. In other words, “I feel the anger that you are feeling”. When therapists reflect feelings, it often has significant effect. This may be the case for several reasons. One, while the therapist may recognise the feeling state of the client, the client may not, and now the reflection helps them get in touch with their own emotions. Two, the recognition that another feels what you are feeling can be a profound moment of connection between people due to the deep sense of empathy provided.

From a Rogerian perspective, therapists who possess the skills of the Basic Listening Sequence and a facilitative way of being with clients, provide a highly therapeutic environment in which psychological change is likely to occur. It is certainly true that often the most profound thing that we can do as helping professionals is to listen deeply to our clients. The notion of ‘deep listening’ has resonance across cultures and reflects an insight that many indigenous cultures have had for generations (Atkinson, 2002). As counsellors our first task is to listen deeply. It is only as we listen that direction for change emerges. To help clients find the pathway of change we also have to help clarify and focus the counselling discussion. Sometimes this entails offering a challenge or helping maintain a keen focus on the problem at hand. The word ‘challenge’ can sometimes infer a blunt note of disagreement. Gerald Egan (Egan & Reese, 2019) is instructive here again when he suggests that a challenge should always be offered empathetically and in fact can be thought of as a form of advanced empathy. This is because to challenge an idea or practice of another with the right attitude actually implies a deep caring for the other.

Communication microskills have to be taught to some degree as discrete skills. However, the reality of any genuine interlocution is that it should be a seamless exchange of ideas and feelings. We only break communication down into its component parts to clarify and practise them. Skills training like any skill development requires practice and then a reintegration into the whole. A pianist practises scales not so that they are good at scales on their own but so that they can play a concerto seamlessly. Similarly, we practise communication skills so that they provide a seamless interchange in the moments of counselling.

Person-centred and Experiential Therapies

Person-centred therapy while a well-developed and celebrated approach in its own right, has had a profound effect on counselling and psychotherapy as a whole. Rogers was one of the earliest researchers to highlight the centrality and importance of the therapeutic relationship and of the role of empathy within therapy. His championing of the phenomenological paved the way for other approaches to draw on experiencing-in-the moment as a foundational concept. Other humanistic therapies such as focusing, gestalt and existential therapy all share this emphasis on the phenomenology of experience as central to the therapy process. Today while there are several different person-centred associations worldwide, it is common to find therapists who share this phenomenological foundation combine organisationally seeing themselves as what is sometimes referred to as the “Tribes of the Person-centred Nation” (Cooper, 2024).

Reflective Activity

Questions for Reflection

- What are key tenets of the view of the person within the person-centred approach to therapy?

- Of the six core conditions which do you feel will be most challenging for you to provide? Why?

- What aspects of the approach resonated with you and what parts did you find limited or confusing?

- Rogers articulated stages in the therapeutic process based on people’s capacity to attend to their experience in-the-moment. How might this approach be substantially different to approaches such as CBT or solution-focused therapy?

- How might we differentiate between emotions and feelings? What is the difference?

References

Atkinson, J. (2002). Trauma trails: Recreating song lines: The transgenerational effects of trauma in Indigenous Australia. Spinifex Press.

Barrett-Lennard, G. T. (1962). Dimensions of therapist response as causal factors in therapeutic change. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 76(43), 1-36. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093918

Cooper, M. (Ed.). (2024). Tribes of the person-centred nation: An introduction to the world of person-centred therapies (3rd ed.). PCCS Books.

Egan, G., & Reese, R.J. (2019). The skilled helper: A problem-management and opportunity-development approach to helping (11th ed.). Cengage.

Gendlin, E. T. (1969). Focusing. Psychotherapy: Theory, research and practice, 6(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088716

Gendlin, E. T. (2007). Focusing. Bantam Books.

Heidegger, M. (1959). An introduction to metaphysics. Yale University Press.

Husserl, E. (1931). Ideas: General introduction to pure phenomenology. Routledge.

Ivey, A. E., Ivey, M. B., & Zalaquett, C. P. (2022). Intentional interviewing and counseling: Facilitating client development in a multicultural society. Cengage.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396.

McLeod, J. (2013). Introduction to counselling. McGraw-Hill Education.

Penagos-Corzo, J. C., Cosio van-Hasselt, M., Escobar, D., Vázquez-Roque, R. A., & Flores, G. (2022). Mirror neurons and empathy-related regions in psychopathy: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and a working model. Social Neuroscience, 17(5), 462–479.

Rasmussen, B., & Bliss, S. (2014). Beneath the surface: An exploration of neurobiological alterations in therapists working with trauma. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 84(23), 332–349.

Rogers, C. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045357.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, C. (2011). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Constable.

Sanders, P. & Hill, A. (2014). Counselling for depression: A person-centred and experiential approach to practice. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Stiles, W. B., & Horvath, A. O. (2017). Appropriate responsiveness as a contribution to therapist effects. In L. G. Castonguay & C. E. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others?: Understanding therapist effects (pp. 71–84). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000034-005

Truax, C. B., & Carkhuff, R. R. (1967). Toward effective counseling and psychotherapy: Training and practice. Aldine Publishing Co.