11 Professional Practice

Jim Schirmer and Kate Witteveen

“Counselor professional identity is the integration of professional training with personal attributes in the context of a professional community.” (Gibson et al., 2010, p. 21)

“Counselors’ identities differ from identities formed in many other professions because. in addition to forming attitudes about their professional selves. counselors develop a “therapeutic self that consists of a unique personal blend of the developed professional and personal selves” (Skovholt & Ronnestad, 1992. p. 507).” (Auxier et al., 2003, p. 25)

Key Takeaways

- An understanding of the professional demands of practising counselling and psychotherapy in a real-world context

- The importance of self-awareness as a counsellor, and the essential areas for self-reflection

- The attitudes, awareness, skills and actions needed to create cultural safety for clients

- The common standards and requirements that are set out by the counselling and psychotherapy profession

Introduction

The previous chapters of this book have covered some of the essential elements of practice, including:

- The underlying philosophy, research and neurobiology of therapeutic change;

- The enduring ideas of major theories of psychotherapy that inform the practice of counselling;

- The essential therapeutic processes that take place within the counselling relationship; and

- The foundational skills that counsellors need to apply in practice.

As authors, we take the position that these are essential features of practice. That is, any practitioner in this field needs to have these foundations in place in order to safely and effectively offer psychotherapy to clients.

It is on the basis of this foundational knowledge and skillset that counsellors step out into the world as professionals. This usually first happens in training during an internship or practicum experience, but soon enough it will happen as a fully qualified graduate. It is at this point that new practitioners of counselling realise that professional practice is more than just having certain theories and practical competencies; rather, it also involves fulfilling your responsibility to certain expectations and standards.

Pellegrino (2002) explains it in this way:

Profession means, in its etymological roots, to declare aloud, to proclaim something publicly. On this view professionals make a “profession” of a specific kind of activity and conduct to which they commit themselves and to which they can be expected to conform. The essence of a profession then is this act of “profession” – of promise, commitment and dedication to an ideal. (p. 379)

Thus, when you go into the world and profess that you are a counsellor or a therapist, and ask someone, ‘How can I be of help to you?’, you are making a promise and a commitment to that person and to the community. As such, you then have a responsibility to honour the trust that is being placed in you by fulfilling the commitment that you have made.

This “act of profession” is an act of implicit promise making that establishes a covenant of trust at the [practitioner’s] voluntary instigation. This self-imposed trust covenant imposes obligations on the professional from the moment it is made. (Pellegrino, 1995, p. 267)

Two conclusions can be drawn from this aspect of professionalism. Firstly, to be a professional is inescapably and invariably an activity that must consider the role of ethics. As the previous paragraphs have demonstrated, being a professional involves a spectrum of ethical considerations: promises, commitments, trust, obligations and responsibilities. It is not that ethics is something that gets added to professional practice, but rather that it is something that that is inseparably interwoven into the very fabric of what it means to declare yourself as a professional. As such, becoming a professional requires you to reflect on yourself as an ethical being.

Secondly, to be a professional is to put your knowledge into practice in a context. This is the difference between being a student of counselling and a practitioner of counselling. A practitioner does not just learn their field, but also applies it. Therefore, a practitioner must choose a place to apply their skills: a real-life setting in which to put their knowledge and skills to work. Consistent with ecological theories of systems (e.g. Bronfenbrenner, 1977), your work as a counsellor is nested within relationships (e.g. colleagues and workplaces), communities, policies and laws, economics, media, social attitudes and norms, and historical events.

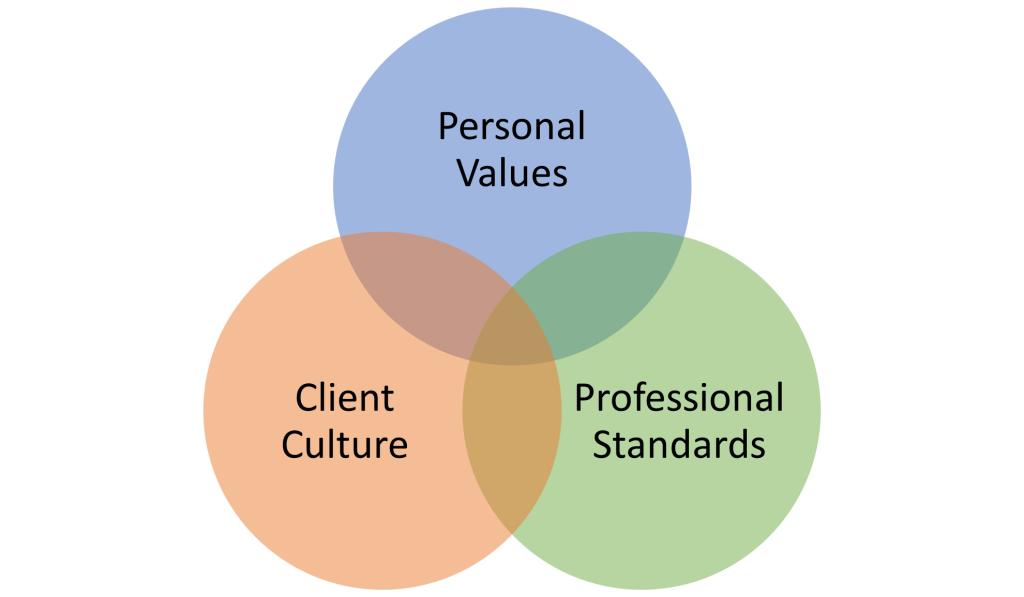

As such, along with knowledge and skills, the ‘practice of counselling and psychotherapy’ also requires you to fulfil your professional commitments within the context in which you practise therapy. The fulfilment of this professional commitment exists in the intersection of three different (and sometimes competing) sets of values and standards:

- Your own personal values

- The worldview and expectations of your client

- The standards set out by the workplace and the profession.

Figure 1. Intersecting Values and Standards

As a result, the practice of psychotherapy frequently requires reflecting on and adapting to the interaction between these three sets of expectations. There will quite often be a strong (or at least very close) synergy between these three areas, meaning that your practice can congruently express your values, meet your client’s expectations, and fall within the professional standards, all at the same time. However, it is possible that, at times, the realities of the context may create difficulties and dilemmas in the form of a dissonance between these three sets of expectations.

The purpose of this chapter is to briefly introduce you to some major considerations of each of these three areas of professional expectations. The treatment of this topic is not meant to be exhaustive, as you will likely gain a deeper knowledge of this through other aspects of training, further reading, and experience in the field. Rather this chapter is designed to have you reflect on three initial questions to prepare you for professional practice in context:

- What are my guiding values and principles as a professional?

- How might I need to adapt to the worldviews, expectations and cultures of my clients?

- What professional standards do I need to be aware of in practice?

Personal Values and Standards

A cornerstone of professional practice as a counsellor is self-awareness. Self-awareness is valued by all approaches to psychotherapy and is an integral part of all training programs (McLeod, 2019). There are several reasons why self-awareness is often seen as an indispensable quality for counsellors to possess:

- Because counselling is fundamentally a relationship, it is crucial that counsellors have a deep understanding of their interpersonal patterns, needs, issues and defences, as these will turn up in therapy and have the potential to interfere with the client’s process.

- Due to the often sensitive, complex and potentially distressing subjects that are the focus of counselling, counsellors need to be aware of their own vulnerabilities, blind spots, emotions and unresolved issues in order to maintain their own health and wellbeing.

- As therapy is meant to be a safe and non-judgemental space, counsellors need to gain awareness of attitudes, assumptions and biases that might leave the client feeling judged or unsafe.

- Finally, because the person of the counsellor is an influence on the outcome of counselling, greater self-knowledge broadens the capacity for the counsellor’s ‘use of self’ in helping others.

So, what is self-awareness, and how do counsellors go about increasing it? Pieterse et al. (2013) define self-awareness as:

“…therapist’s knowledge and understanding of [self] in relation to values, beliefs, life experiences and worldview … [It is] a state of being conscious of one’s thoughts, feelings, beliefs, behaviours and attitudes, and knowing how these factors are shaped by important aspects of one’s developmental and social history” (pp. 190-191).

This definition highlights a few key areas that counsellors should reflect on to gain greater self-awareness. The first could be referred to as the influence of their history and experiences. Like anyone, a counsellor’s life experiences will have shaped the person they have developed into. One particularly important aspect of this is the counsellor’s social history, which will have shaped their relational patterns and needs. Another key area to be aware of is any lived experience of issues that the client is presenting with, both for the counsellor’s own wellbeing, and also for the potential influence that this may have on the therapeutic process.

A second area for awareness could be termed the counsellor’s psychological and moral schema. This includes a wide range of things such as the beliefs, attitudes, worldview, values and motivations. The value of gaining awareness of these aspects of self is that many of these operate below our conscious awareness. In other words, they act more like assumptions that we bring to the world. Nonetheless, they are highly influential, such as in the following example.

Example

Consider the topic of motivation. Many counsellors would describe their professional motivation as wanting to ‘help others’. While this of course has its merits, there might also be some unexpected undercurrents that a counsellor should explore.

For example, wanting to help another is rarely purely altruistic. Rather, it feels good to be an important person in another person’s life. If we are not aware of how this feeling of importance is motivating us, then we may be tempted to make ourselves indispensable to the other person. That is, if our reward is feeling important, then this may then subtly influence the counselling relationship, such as maintaining the client’s need for us, or feeling disappointed if someone doesn’t need us anymore.

Another side of helping is feeling influential. If we have influence in another person’s life, it can leave us with a feeling of power. If we are working from this motivation, and someone doesn’t accept our help, or is passive-aggressive, we might suddenly find ourselves frustrated. There might be a sudden instinct or urge to try to get our way. As such, an unchecked motivation can have strong influences on the relationship and the client.

A third area for counsellor self-awareness is the awareness of the moment-to-moment thoughts, feelings and behaviours. This is sometimes termed the skill of immediacy: being able to pay attention to what is going on for you, here and now. Another word for this is interoception, which is the capacity to perceive physical and emotional states. This first involves recognising how the counselling session might be influenced by things like the counsellor’s physical state (e.g. hunger; tiredness), their emotional reactions (e.g. offence, frustration, affection, pity), or cognitions (e.g. interpretations). This then also involves how the counsellor understands, regulates and possibly uses these reactions.

Given the value and the content of self-awareness, it is worth briefly mentioning some of the common ways that therapists develop self-awareness. Broadly, this process could be called reflection, i.e. that self-reflection is the means to gain self-awareness. Due to the interpersonal nature of counselling, many practitioners do this reflection in an interpersonal environment, such as their personal therapy or as part of a personal development group. However, counsellors might also have personal processes of reflection, such as journalling, art, or contemplative practices. Of course, life experience and work experience provide stimuli for reflection, with the latter often processed in supervision or among peers. Whatever the method, the important thing is that you have a regular, sustained practice of reflection on yourself as a person and a professional.

Client Culture and Worldview

A second dynamic to professional practice is recognising and adapting to the individuality of the client and their worldview, culture and expectations. While the principles of recognising and adapting to the individuality of the client undergird practically all the skills and processes in this book, the emphasis in this section is on the ethical requirement of the professional counsellor to create a safe environment for their clients.

The basis of this principle is the reality of diversity. Just as one might express a paradox such as ‘the only constant is change’, so too it might be accurate to say that in counselling the only true universal is difference. Even veterans of this practice can be surprised by the sheer spectrum of ways that people view, experience and act within the world. So, how, as a professional, do we go about fulfilling our promise and responsibility in the context of client diversity?

A substantial proposition of the answer to this question could be summarised under the term ‘cultural safety’. Creating a safe therapeutic environment is a foundational professional responsibility. Some authors (Eckermann et al., 1994, as cited in Williams, 1999) have described this culturally safe environment in the following way:

“an environment which is safe for people; where there is no assault, challenge or denial of their identity, of who they are and what they need. It is about shared respect, shared meaning, shared knowledge and experience, of learning together with dignity, and truly listening” (p.213).

Implicit in this definition are two elements. Firstly, a culturally safe environment can be defined by what is not there, namely an absence of prejudice, judgment, coercion, paternalism or any other factor that dehumanises, devalues or demeans the person and their experience. Secondly, and more substantively, a safe environment is marked by the presence of respect and dignity in which the worldview, knowledge, experience and culture are actively acknowledged, heard and incorporated into the therapeutic environment.

Of course, the range of possible areas of diversity is wide. Any individual client will represent a unique constellation of factors such as (but not limited to) culture, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, socio-economic status, and level of education. So, what does it take to make safe professional environments for our clients? The American Counselling Association (Ratts et al., 2016) summarises the competencies needed for multicultural counselling under four headings:

- Attitudes and beliefs

- Knowledge (or awareness)

- Skills

- Action.

This section will briefly introduce some of the major features of professional practice in each of these four areas.

Attitudes and Beliefs

A recurring theme in most accounts of culturally safe professional practice is that creating safety is not just a matter of knowing about other cultures or saying the right words. Rather, it also involves some inner work of examining our attitudes and beliefs in order to consider the effects these have on clients. Thus, many contemporary approaches to diversity do not just mention ‘competency’, but also attitudes of humility, sensitivity, empathy and wisdom (Sullivan, 2008).

At one level, this reflection on attitudes and beliefs is about fostering awareness of pre-existing attitudes and beliefs that might benefit or inhibit client safety. Our life experiences, upbringing and own cultural discourses leave us all with presuppositions, assumptions and cognitive scripts, many of which are below our awareness. Even so, they have an influence in how we act and communicate with others. Compassionately and honestly reflecting on these has the potential to avoid inadvertently creating an unsafe environment for our clients.

Example

In one of Irvin Yalom’s (2012) stories of psychotherapy – titled “Fat Lady” – the author offers a raw and sometimes uncomfortable reflection on his attitudes towards weight and how these impacted upon a client, even without his awareness. While some have criticised the content and the impunity with which he shared his judgements (e.g. Fuller, 2017), the essay still stands as an example of a therapist wrestling with their own inherited attitudes and biases.

If you were honest with yourself, are there any attitudes or beliefs that you need to reflect on in terms of how they might impact client safety?

Along with becoming aware of our pre-existing assumptions and beliefs, cultural safety is also about cultivating the kind of attitude that enables one to adopt an open, sensitive and respectful presence in counselling. A major term that has been used to describe this type of attitude is ‘cultural humility’ (Mosher et al., 2017). Cultural humility has many aspects, including:

- being aware of our limitations, leading to a willingness and openness to learn new cultural information;

- a respect for the knowledge and expertise of the other person, leading to a stance of listening, learning and not making assumptions; and

- a willingness to divest power, leading to a more mutual partnership of knowledge.

As such, an attitude of humility has the potential to create a safe environment for the client, their culture and their worldview.

Knowledge: Awareness for Empathy

A second feature of creating a culturally safe therapeutic space for clients involves the counsellor developing a growing awareness of the worldviews and lived experiences of their clients. As mentioned earlier, each person you see will have their own combination of social groups and identities that have shaped their life and their experience. It is not reasonable to think that any counsellor will be an expert in all possible cultures and experiences; furthermore, it is also questionable whether ‘expertise’ is even desirable, given that it is a stance that operates against the humility discussed in the previous section.

In contrast, the ‘knowledge’ needed to create culturally safe environments is perhaps better categorised as an ongoing attitude of openness, sensitivity and awareness. Chung and Bernak (2002, pp. 157-158) list some prominent areas that counsellors need to develop awareness in, leading to questions like:

- What are the social contexts of my client (e.g. family, community, culture)? What norms, values and worldviews exist within these groups? How do these influence my client?

- What are the help-seeking and healing practices that are common in my client’s culture? How does this culture understand ‘mental health’, the nature and cause of ‘symptoms’, and the steps in ‘treatment’?

- What is the historical and sociopolitical background of the social groups to which my client belongs? How does this background influence the client in the present?

- What psychological or social adjustments might the client need to make in navigating various roles and contexts? What adjustments might the client be feeling they need to make to ‘fit in’ to therapy?

- Where in their life might the client experience inequality, discrimination, prejudice or oppression because of a social group or identity? How have dynamics of privilege and marginalisation been experienced by the client?

An awareness of these types of issues has the potential to shape the course of therapy in several ways. Firstly, this awareness helps the counsellor to remain sensitive and flexible in the formation of the therapeutic relationship. By attending to the client’s experience in these areas – and, conversely, by not basing the therapy on the assumption that the client’s experience is the same as the counsellor’s – the counsellor increases the chance that they will show the empathy needed for the client to feel heard and understood. Furthermore, by understanding the norms of roles and communication that the client is bringing to therapy, the counsellor may be able to adjust their interpersonal style to facilitate a more comfortable interaction for the client. It is also important for the counsellor to be sensitive to potential power dynamics that may leave the client feeling unsafe.

Moreover, by understanding what the client might be expecting from the encounter, the counsellor can help to form the therapeutic alliance by adjusting their approach or (where needed) negotiating the basis on which they and the client might work together. In this way, an awareness of the client’s social background helps to shape therapy by accounting for their worldview in all aspects of the therapeutic process, including case formulation and the selection and implementation of interventions. By understanding the way in which the client might understand their problems and their resolution, the counsellor is more likely to be able to shape the goals and tasks of therapy in way that will be acceptable and safe for the client.

Skills for Promoting Safety

While awareness of ourselves and our clients is a necessary foundation for culturally safe practice, it is rarely sufficient. Rather, cultural safety also requires counsellors to develop the skills needed to practise in a sensitive and flexible way. If the client is to experience a therapeutic environment free from judgement and discrimination, which has limited barriers to receiving care and honours their perspective and self-determination, what types of skills would a counsellor need to possess?

Sue et al. (2012) summarise the skill component of culturally safe practice as the capacity to be responsive, flexible and adaptable in your approach to helping others:

“The multicultural skills component of cultural competence requires that counselors effectively apply a variety of helping skills when forming a therapeutic alliance… [I]t is important to individualize the choice of helping skills and avoid a blind application of techniques to all situations and all populations… It is important to individualize relationship skills and to consistently evaluate the effectiveness of our verbal and nonverbal responses to the client” (p. 351).

From this definition, it is possible to draw out two major capacities that counsellors need in this area. Firstly, flexible and adaptable counsellors need to have a capacity for higher-order thinking skills. That is, they do not just have the ability to understand, recall and apply, but also to analyse, evaluate and create. In other words, rather than just applying their known therapeutic theories and techniques, culturally responsive counsellors can think critically about the appropriateness for the client, and creatively adapt their practice to match the client’s needs. In this way, the purpose of processes like rapport-building, assessment, formulation and intervention can still be achieved, but in ways that are individualised to the client.

The second area of capacity for counsellors is the breadth of skills in communicating with and relating to others. These communication skills include both listening and responding, as the safe therapeutic environment needs both understanding and responsiveness. Again, the key here is adaptability. A culturally safe counsellor will have the interpersonal agility to adapt elements of their communication style; for example, their formality and directness, the language, images and metaphors used, the volume of their content, and their rhetoric. This applies to all parts of the counselling process including relationship-building, formulation and intervention.

Exercise

Consider how you might adapt your communication in the following circumstances:

- Building rapport with a client who comes from a culture that values formality and hierarchy, and therefore expects the counsellor to be the expert and to lead the session.

- Talking with a client who is displaying symptoms of depression but who is from a generation where mental illness was considered ‘madness’ or ‘insanity’ and therefore carries a lot of stigma.

- Discussing how to respond as a parent to a child who has come out as gay when a client has religious beliefs that are strongly heteronormative in their approach to sexuality.

Action: Safety Through Justice

A final area of practice for counsellors wanting to create culturally safe therapeutic environments for clients is the capacity for action on issues of injustice or oppression. In this area of practice, counsellors are asked to consider how they might exercise their agency to take proactive action in the direction of greater social equality and justice.

While this perspective is not new in therapeutic theory – it was particularly championed through the perspectives of feminist therapy – it has recently experienced a renewed emphasis in the forms of concepts such as decolonisation, solidarity and liberation (Torres Rivera, 2020). In these perspectives, a more critical approach is taken to reorient counselling practice to consider socio-political aetiologies of human suffering, the impact of dominant discourses and ideologies that oppress or marginalise various people and groups, the power dynamics that are present in professions, and the need for praxis in producing change.

From these principles, other competencies emerge for counsellors who are seeking to create safety through solidarity, liberation and justice (Constantine et al., 2007), including the following:

- Be aware of ways that oppression and inequality might be manifested and experienced by individuals and communities, including a critical reflection on how issues of oppression, power and privilege operate in your own life.

- Maintain an awareness of how dynamics of power or privilege operate within your professional role (including processes of assessment and intervention), and be willing to question and challenge practices that might be marginalising, inappropriate or harmful.

- Be active in collaboratively evaluating and exploring programs and interventions that better address the needs of marginalised populations, including traditional healing practices.

- Work at a systematic level to collaborate, learn and advocate for social change processes.

Importantly, these types of action need to be considered across a range of ecological levels, from the immediacy of intrapersonal and interpersonal, through to action in institutions, communities, public policy, and even the international level.

Reflection Activity

The Cultural Responsiveness Assessment Measure (CRAM; Smith et al., 2023) is a self-reflection tool for mental health practitioners working with First Nations people. This tool is intended to guide practitioners and students to reflect upon their own practice, and enhance self-awareness and capacity to work in a culturally responsive way. This tool includes items pertaining to the following themes:

- Awareness

- Knowledge

- Inclusive relationships

- Cultural respect

- Cultural safety

- Social justice

- Cultural humility

- Cultural competencies (p. 195).

From these themes, it is evident that culturally responsive practice includes a synthesis of knowledge, skills and competencies, about self and about others.

Take a few moments to complete the CRAM (Smith et al., 2023).

Understanding and Maintaining Professional Standards

Being a professional does not just involve mediating between personal values and client expectations. Rather this interaction takes place within a wider social context. As a professional, you not only need to consider your own and your clients’ expectations, but also the expectations of the workplace, your professional bodies, the community and the political and legal system in which you operate. All of these are stakeholders in the work you do, and influence your interactions through both written standards (e.g. laws, policies, codes) and unwritten expectations (e.g. norms, worldviews, cultures).

A major aspect of this is being part of a professional association, the association or body that represents the specialised knowledge and skills of the profession. Professional associations act as the public face of the profession through fulfilling numerous functions. These associations accredit training and have standards for the admittance to the profession. In this way, they help to ensure that all practitioners meet a recognised set of standards. They also have codes of conduct and ethics, which effectively provide accountability for professionals’ behaviour. In this way, if practitioners do not maintain certain standards (both in terms of their practice and their behaviour), they can lose their status as a professional. As such, professional associations provide benefits for all stakeholders. For the professional, they provide credibility. For the public, they provide protection through accountability.

Some major standards that a professional counsellor needs to maintain are (a) ethics, (b) scope of practice and ongoing development, and (c) participation in supervision.

Ethics – Codes and Decision Making

One source of professional standards is a code of ethics. This includes features such as the guiding values and principles of the profession, namely: autonomy, justice, beneficence, nonmaleficence and fidelity (Kitchener & Anderson, 2011), and also particular standards of behaviour related to major aspects of practice. These standards range from what is mandatory (i.e. you must do), to what is permitted (i.e. what you can do), to what is proscribed (i.e. what you cannot do) as a professional.

Exercise

Look up a code of ethics from a major counselling and psychotherapy association (e.g. the Australian Counselling Association, the Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia).

These principles provide the foundation for ethical practice and are helpful in ensuring the safety of clients. However, they may not provide sufficient guidance and clarity in situations in which you encounter complex ethical dilemmas.

In the event of an ethical dilemma, ethical decision-making frameworks provide professionals with a means of systematically evaluating the options available to them and developing a plan of action that is based on a transparent and good-faith application of ethical principles. Many ethical decision-making models have been proposed (see, for example, Johnson et al., 2022 for a review), and you are encouraged to explore these models to see which ones align best with your personal and professional context. Although derived from different theoretical and practice-based frameworks, common elements across ethical decision-making models include the following factors: consultation; considering culture and/or context; making professional and personal judgements; and engaging in ethical and legal considerations (Heller Levitt, 2013, p. 215).

Ethical Decision-making Model Example

The practice-based model proposed by Corey et al. (2024) provides an example of an ethical decision-making model that incorporates these elements into an 8-step model, as follows:

- Identify the problem – This includes conceptualising the nature and type of the problem, e.g. is it an ethical, legal, moral, values problem – or some combination of these?

- Identify the potential issues involved – Consider: What are the competing perspectives and/or concerns? You may like to ask yourself: “Why is this problem a problem?” In this step, it is relevant to consider the context (including culture) in which this problem is being experienced.

- Review the relevant ethical codes – Refer to your professional body’s code of ethics. It is possible that the situation you are navigating is less complex than you first thought and may be specifically accounted for in the code of ethics. Alternatively, the code of ethics will serve as a helpful reminder of the “non-negotiables” that you will need to consider in your decision.

- Know the applicable laws and regulations – As professionals it is our obligation to be familiar with the relevant laws and regulations that govern our practice. It is important to note that some laws that may be relevant to counsellors (such as mandatory reporting legislation) differ across jurisdictions, so you need to ensure you are up to date with those that apply to your work.

- Obtain consultation – It can be a tremendous relief to remember that we are not expected to make complex ethical decisions in isolation. It is appropriate and recommended to seek support from supervisors and/or other experienced professionals as part of your ethical decision-making process.

- Consider possible and probable courses of action – Brainstorm all of the options you can identify, taking into account the unique circumstances of your dilemma.

- Enumerate the consequences of various decisions – Evaluate each of your options from Step 6 through the lens of the ethical (including the ethical principles and the specific ethical guidelines of the code of ethics you consulted) and legal obligations you must consider.

- Decide on what appears to be the best course of action – Taking into account all of the information you have gathered throughout this process, identify the most appropriate option. It is possible that you may need to revisit some of the earlier steps in the model to refine your decision.

Ultimately, the specifics of the ethical decision-making model you choose to implement are less important than the process of careful consideration and reflection that you engage in when you encounter situations that are ethically complex. Like many facets of the counselling process, there are many possible approaches to ethical decision-making, and the usefulness of individual models may vary across counsellors, clients and contexts (Sheperis et al., 2016). It is up to you, as a professional counsellor, to familiarise yourself with ethical decision-making models that are applicable to your practice, and engage with these models, as appropriate, when navigating difficult ethical situations.

Scope of Practice and Professional Development

Another important aspect of maintaining professional standards is holding a ‘scope of practice’. A scope of practice defines the activities a practitioner is permitted to undertake in their professional role, and (by extension) shows the limits to their practice (often referred to as those activities ‘beyond the scope of practice’). In layperson’s terms, a scope of practice defines what you can and cannot do in your role as a counsellor or psychotherapist. As a professional it is important to:

- know the limits of your scope of practice

- make sure that every service you offer is based on adequate knowledge, training and skills

- refrain from making false claims about your qualifications or competence, and do not allow others to do so either.

Some aspects of a counsellor’s scope of practice are static. For example, counsellors virtually never have the scope to provide a conclusive mental health diagnosis, nor can they prescribe medication. Other aspects are more dynamic. That is, your scope of practice may expand across your career, such as working with particular populations (e.g. children), presenting issues (e.g. psychosis), interventions (e.g. Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing, i.e. EMDR), or modalities (e.g. couples and families), as you undertake additional training and/or gain specific experience.

A major professional standard relating to competence and scope of practice is continuing professional development. That is, after your initial qualification in counselling, it is important that you keep up to date with emerging knowledge in the field and that you continue to expand your knowledge and skills. This expectation is so important that most professional associations require practitioners to meet minimum requirements (e.g. 25 hours per year) of professional development in order to maintain their membership as a professional. This professional development often takes the form of a training event (e.g. workshop, conference, course or online training), but professional bodies often also recognise some activities such as professional reading, imparting knowledge (e.g. writing and presenting), or participation in peer learning groups.

Supervision

A final essential standard for professional counsellors and psychotherapists is participation in ongoing supervision. Supervision has been described as a:

“…mechanism for registered counsellors and psychotherapists to review caseloads with an experienced practitioner and to develop the best therapeutic outcomes for the client, to discuss any concerns or ethical issues that may arise, and to reflect on the impact of the client work on the counsellor in an effort to improve self-care” (Schirmer & Thompson, 2021b, p. 10)

Given that the aim of supervision is to provide some support, guidance and review of the work of the counsellor, the practice of supervision is an essential system for both the professional development of counsellors and the quality assurance of the care provided to practitioners and the public. In this way, it is highly valued and widely used in human service professions such as counselling, psychotherapy, psychology, psychiatry, social work and mental health nursing (Barletta, 2017).

There are many different models for supervision, and much of what you learn about supervision will be through your experience as a supervisee in practice. Still, most supervision fulfils at least three basic functions, which have been termed the formative, restorative and normative functions (Proctor, 1988). Firstly, as a formative practice, supervision is educational, in that you engage in learning through a mentoring-like relationship where you reflect on cases, themes and questions from your work. Secondly, as a restorative practice, supervision is supportive in that it is meant to monitor impact of the work, mitigate stress and promote growth in the counsellor. Finally, supervision has a normative or managerial function in that it also provides quality control through accountability to the ethos and standards of the profession, creating a common standard across the profession. These three functions each present unique contributions to the practice of counsellors, and research has shown that an overwhelming proportion of practising counsellors both value and receive benefit from supervision (Schirmer & Thompson, 2021a).

Conclusion: On the Value of Wisdom to Practice

This chapter has explored some of the major dynamics of stepping out as a counsellor into the real-world context of practice. In doing so, we often have to mediate between our own personal values, the worldview and expectations of our clients, and the standards set out by the workplace and the profession. The reality of mediating between these various perspectives cannot be reduced to knowing and following rules. Rather, it is a process of constant reflection, awareness and judgement, which is perhaps best summarised in the word wisdom.

In their attempt to define “wisdom”, Zhang et al. (2023) identified more than twenty definitions in the literature, none of which were universally recognised. In synthesising these definitions, two common elements were recognised, namely:

- A cognitive and affective component (i.e. intrapersonal knowledge and emotional mastery)

- Concern for the welfare of humanity (i.e. interpersonal awareness and altruistic intention).

From these elements, we can determine that wisdom involves the capacity to integrate knowledge acquired through learning to new and different situations (“wit”) and the discernment, motivation and ability to apply that knowledge in an ethical way (“virtue”).

By this conceptualisation, it is apparent that the acquisition of wisdom is a process that occurs throughout your professional journey. It is not something you collect upon your graduation along with your degree. Rather, as you engage in your professional practice by applying your knowledge, skills, ethical decision-making processes and continuous self-reflection, you will enhance your capacity to understand “what is” (wit) and “what to do” (virtue) (Zhang et al., 2023).

For counsellors, wisdom in practice can be understood as a progression from needing to know “the single best thing to do”, to recognising that, in many cases, the “best thing to do” depends on many factors that need to be considered on a case-by-case basis. Wisdom in practice requires the recognition and integration of a constellation of intrapersonal, interpersonal and sociocultural factors, as well as the elements of the therapeutic process we have explored in this book.

In this chapter, we have considered the intersection of personal values and standards, clients’ culture and worldview, and ethical and professional standards, which influence our identity and practice as counsellors. It is apparent that “being” a professional is not something we attain upon meeting a certain training threshold. Rather, it involves a process of continuously “becoming”, as we strive to integrate our knowledge and experiences in ways that enhance our wisdom. In so doing, we are able to achieve our purpose of being professionally and ethically competent counsellors which, ultimately, means we help our clients.

Additional Reading

The following books provide some practical guidance and exercise on undertaking self-reflection as a trainee counsellor.

McLeod, J. (2009). The Counsellor’s Workbook: Developing a Personal Approach (2nd ed.). Open University Press.

McLeod, J., & McLeod, J. (2014). Personal and Professional Development for Counsellors, Psychotherapists and Mental Health Practitioners. McGraw Hill.

References

Auxier, C.R., Hughes, F.R., & Kline, W.B. (2003). Identity Development in Counselors-in-Training. Counselor Education and Supervision, 43(1), 25-38. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01827.x

Barletta, J. (2017). Introduction to clinical supervision. In N.J. Pelling & P. Armstrong (Eds.), The practice of counselling and clinical supervision (2nd ed.) (pp.15-35). Australian Academic Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Chung, R. C.-Y., & Bemak, F. (2002). The Relationship of Culture and Empathy in Cross-Cultural Counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80, 154-159. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2002.tb00178.x

Corey, G., Corey, M., & Corey, C. (2024). Issues and ethics in the helping professions (11th ed.). Cengage.

Constantine, M. G., Hage, S. M., Kindaichi, M. M., & Bryant, R. M. (2007). Social justice and multicultural issues: Implications for the practice and training of counselors and counseling psychologists. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85, 24-29. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00440.x

Fuller, C. (2017). The fat lady sings: A psychological exploration of the cultural fat complex and its effects. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429481741

Gibson, D.M., Dollarhide, C.T., & Moss, J.M. (2010). Professional Identity Development: A Grounded Theory of Transformational Tasks of New Counselors. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50(1), 21-38. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2010.tb00106.x

Heller Levitt, D. (2013). Ethical decision-making models. In D. Heller Levitt & H. J. Hartwig Moorhead (Eds.), Values and ethics in counselling: Real-life ethical decision making (pp. 213-217). Taylor & Francis Group.

Johnson, M.K., Weeks, S.N., Peacock, G.G., & Domenech Rodriguez, M.M. (2022). Ethical decision-making models: A taxonomy of models and review of issues. Ethics & Behavior, 32(3), 195-209. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2021.1913593

Kitchener, K. S., & Anderson, S. K. (2011). Foundations of ethical practice, research, and teaching in psychology and counseling (2nd ed.). Routledge.

McLeod, J. (2019). An introduction to counselling and psychotherapy: Theory, research and practice (6th ed.). McGraw Hill.

Mosher, D.K., Hook, J.N., Captari, L.E., Davis, D.E., DeBlaere, C., & Owen, J. (2017). Cultural humility: A therapeutic framework for engaging diverse clients. Practice Innovations, 2(4), 221-233. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/pri0000055

Pellegrino, E.D. (1995). Toward a virtue-based normative ethics for the health professions. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 5(3), 253-277. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/ken.0.0044

Pellegrino E.D. (2002). Professionalism, profession and the virtues of the good physician. The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York, 69(6), 378–384. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12429956/

Pieterse, A. L., Lee, M., Ritmeester, A., & Collins, N. M. (2013). Towards a model of self-awareness development for counselling and psychotherapy training. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 26(2), 190-207. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2013.793451

Proctor, B. (1988). Supervision: A co-operative exercise in accountability. In M. Marken & M. Payne (Eds.), Enabling and Ensuring: Supervision in Practice (2nd ed.) (pp. 21-34). National Youth Bureau and Council for Education and Training in Youth and Community Work.

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar‐McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Schirmer, J., & Thompson, S. (2021a). Supervision from two perspectives: Comparing supervisor and supervisee experiences. Australian Counselling Research Journal, 15, 33-39. https://www.acrjournal.com.au/resources/assets/journals/Volume-15-SS-Issue-2021/Manuscript6%20-%20Supervision%20from%20Two%20Perspectives.pdf

Schirmer, J., & Thompson, S. (2021b). Supervision in counselling: a national report on the practice, content and value of supervision. Counselling Australia, 22(4), 10-26.

Sheperis, D., Henning, S., & Kocet, M. (2016). Ethical decision making for the 21st century counselor. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071801154

Smith, P., Rice, K., Schutte, N., & Usher, K. (2004) Development and validation of the Cultural Responsiveness Assessment Measure (CRAM): A self-reflection tool for mental health practitioners when working with First Nations people. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 70(1), 190-200. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640231204211

Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2012). Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice. Wiley.

Sullivan, B. (2008). Counsellors and counselling: a new conversation. Pearson Education Australia.

Torres Rivera, E. (2020). Concepts of liberation psychology. In L. Comas-Díaz & E. Torres Rivera (Eds.), Liberation psychology: Theory, method, practice, and social justice (pp. 41–51). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000198-003

Williams, R. (1999). Cultural safety – what does it mean for our work practice? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 23(2), 213-214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.1999.tb01240.x

Yalom, I. D. (2012). Love’s executioner & other tales of psychotherapy. Basic Books.

Zhang, K., Shi, J., Wang, F., & Ferrari, M. (2023). Wisdom: Meaning, structure, types, arguments, and future concerns. Current Psychology, 42(18), 15030–15051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02816-6