6 Psychodynamic Theory

Denis O'Hara

“The therapist’s task is to reach to the heart of loneliness and speak to that.” – Robert Hobson

Key Takeaways

This chapter traces key ideas in the development of psychodynamic approaches to therapy.

- Unconscious processes such as defence mechanisms, splitting, and projective identification are explained and their relevance for the therapeutic process identified.

- The importance of therapy being a safe ‘holding environment’ is briefly explored.

- What is described as a ‘relational turn’ in psychodynamic theory is highlighted.

- An integrative view of psychodynamic theory is described in brief.

- Understanding the place of communication microskills within a psychodynamic framework is discussed.

Overview

This chapter provides a general introduction to modern psychodynamic theory. There are many contributors to the development of the theory and as such, it is beyond the scope of this chapter to cover the full breadth of contribution. It is true to say that there is no one psychodynamic theory as such, but many theories have a broadly common theoretical foundation and practice focus. Our modest aim is to provide a brief description of the development of the collected theory and to explain commonly held psychodynamic views about psychic structure and the therapy process, what might today be called, an interpersonal psychodynamic approach to counselling and psychotherapy.

Early Developments

Psychodynamic theory owes a great deal to Freud’s (1923) psychoanalysis and his key ideas about intrapsychic structure. Concepts such as the unconscious, objects, the impact of anxiety, the idea of psychological development in general, transference and countertransference, splitting, and other concepts form the foundation of psychodynamic theory. There are, however, some major differences between Freud’s views and modern psychodynamics. One of the first significant departures from Freudian theory was the shift away from understanding biological drives as the primary explanation for human behaviour. Freud’s classical intrapsychic structure of id, ego and super-ego is an essential feature of psychoanalytic theory. While many theorists appreciate the notion that the psyche is divided or organised into different sub-structures or functions, the focus on the influence of libidinal and aggressive drives as formulated by Freud is not generally a view shared by psychodynamic theorists.

Ronald Fairbairn

One of the earliest theorists to move away from the notion of drive theory and set the scene for the development of a psychodynamic view of the person was Scottish psychiatrist Ronald Fairbairn. Fairbairn (1952) proposed that people are not principally driven to relate to other people (i.e., objects) to satisfy pleasure-seeking drives, but are naturally relationship seeking. In Freud’s scheme, when an individual has strong Id impulses (e.g., libidinal/sexual) they seek satisfaction or relief of the drive through objects. Contrary to Freud, Fairbairn believed libido is not a pleasure-seeking force but an object seeking-one oriented towards forming and maintaining relationships.

Instead of Freud’s intrapsychic structure of id, ego and superego, Fairbairn (1944) proposed what he called an endopsychic structure containing three different features:

- Central ego: The part of the self that engages in realistic and adaptive interactions with the external world.

- Libidinal ego: The part of the self that is driven by the desire for gratifying relationships.

- Antilibidinal ego: The part of the self that harbors negative feelings and defenses against disappointment and rejection.

From a psychodynamic perspective, we internalise or introject experiences and representations of others into complex cognitive/affective frames of the self and other. Within this model, psychological disturbances arise from problematic internal object relationships rather than unresolved instinctual conflicts.

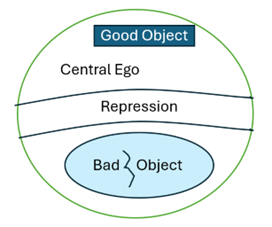

The notion that the ego can be split into different components is a central idea within psychodynamic theory. Most psychodynamic theorists would agree that through developmental challenges and relational injuries individuals protect themselves, largely unconsciously, by repressing or pushing down into the unconscious aspects of their experiences. While theorists don’t always agree on the exact form of this repression and splitting of the self, there is general agreement that splitting as a process exists. Fairbairn was one of the first to provide a detailed explanation of the process and structure of splitting. He asserted that in the process of relating with primary others we experience both positive and negative interactions. In other words, we can experience the other as good or bad in given moments. As it is difficult to relate to an aspect of another that is experienced as bad in the real world, Fairbairn suggests that we repress the ‘bad other’ into our unconscious and maintain the ‘good other’ in our conscious awareness. The notion of a ‘bad other’ does not necessarily mean that the other person is bad; rather, it is better to think of this as an experience of the other which may range between an uncomfortable aspect of their personality or behaviour and objectively harmful behaviours of the other such as in emotional or sexual abuse. A representation of this psychic structure is seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Fairbairn’s Intrapsychic Structure

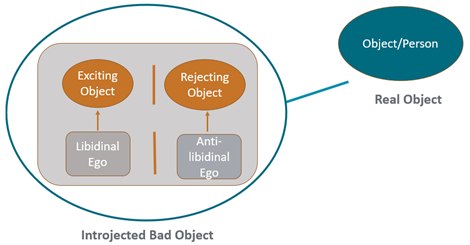

The difficulty with splitting the perceived bad aspects of the other into the unconscious is that some aspects of what is uncomfortable about the other, and therefore considered bad, may actually be more enticing aspects of the other with which we are not ready to engage. Hence, the fact that the other may be strong and spirited, while somewhat disconcerting for a child, may also be exciting and alluring. At the same time, there may be aspects of the other that are fundamentally experienced as harmful and therefore bad. In recognition of this reality, Fairbairn argued that the object was further split into the exciting object and the rejecting object and that a part of the ego is attached to both. This can be seen in the Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Introjected Bad Object

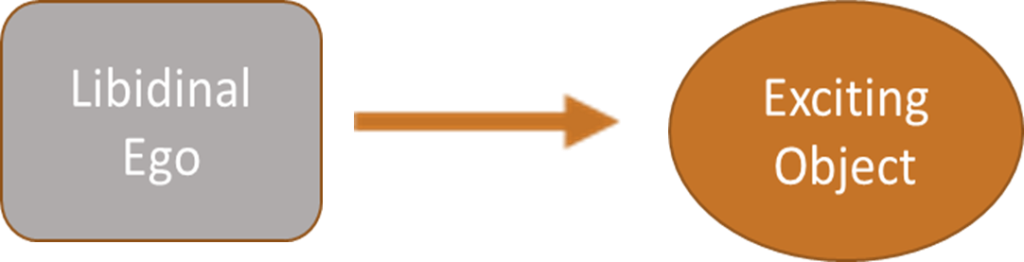

When the split off ‘bad object’ is not integrated into a holistic view of the other as in the normal maturation process, the individual is more likely to engage in an unconscious relationship with the perceived bad aspect of the other. In the case of the exciting (bad) object, the unintegrated ego is still desiring attachment to the object, seeking from it the qualities/relationship which the ego perceives has been withheld or missing. This unintegrated position produces a relentless pursuit or expectation of the other that, in reality, the other cannot fulfil.

Figure 3. Connection between Introjected Ego and Bad Object

The ego is in effect saying. “Be who I want you to be” “Relate to me the way I want you to relate to me”. Underneath the pursuit is a desperation which is fuelled by the unconscious despair that maybe the other does not give the individual what they want because there is something unacceptable or wrong with them. One could say that this repressed confusion is filled with a shame in being. A central action of the maturation process is the progressive disillusionment of this unconscious expectation through growing awareness. The individual has to come to realise that they cannot gain from the other what they are seeking. This realisation leads to a grieving process, a letting go of unrealistic expectations and ultimately to a more integrated self.

A lot more can be said about the implications of Fairbairn’s endopsychic structure but that is beyond our brief in this chapter.

Melanie Klein

Melanie Klein, along with Fairbairn, Donald Winnicott, Anna Freud, and others, collectively contributed to what has been referred to as the British Object Relations School. This is not to say these theorists agreed with each other on all aspects of theory, but they did hold many essential ideas in common as noted above. Klein, Winnicott, and Anna Freud explored the nature of early psychological development. Klein, for example, proposed different stages of intrapsychic development and also noted that splitting was a natural aspect of the human process. Somewhat differently to Fairbairn, Klein (1946) believed that we did not just split the ‘bad object’ into our unconscious but also the good. Hence, we have introjected aspects of a good and bad self and a good and bad other. Similar to Fairbairn, Klein understood splitting to occur as a way of managing emotionally overwhelming and frustrating experiences.

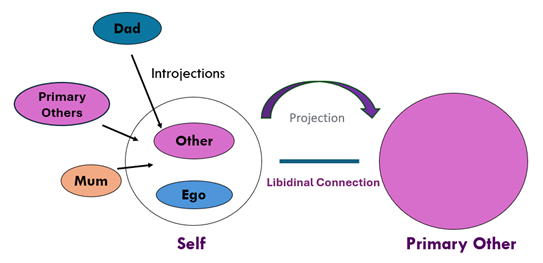

Klein (1946) asserted that splitting was a normal part of psychological development because it was a primitive (meaning early) way of managing relational stress and anxiety. However, in mature adult development the aim is to reconcile the split aspects of the ego and object/other so as to reach a more integrated view of self and other. This process is more obviously seen in late teenage and early adulthood where the individual begins to realise that one’s parents have both strengths and limitations, that they like all people, are a mixture of both appealing and unappealing qualities. You can see in the Figure 4 below how we introject or internalise aspects of primary others and our experience of them into our inner schemata or models of self, other, and the world.

Figure 4. Introjection and Projection

An important contribution of psychodynamic theory is an explanation of what happens when the process of maturation or psychological integration does not progress successfully. In reality, no one reaches a perfect level of maturation and hence we are all in the process of development throughout our lives. Freud proposed that we all experience anxiety in living and manage our anxiety through defence mechanisms. Psychodynamic theorists agree that we defend against the experience of anxiety through such mechanisms and as such these mechanisms provide a window into what is occurring in an individual’s intrapsychic experience. Freud’s list of defence mechanisms is well known and includes:

- Repression: Unconsciously blocking unacceptable thoughts, feelings, and impulses from conscious awareness. For example, a person who has experienced a traumatic event may not remember it because it is repressed.

- Denial: Refusing to accept reality or facts, thereby blocking external events from awareness. For instance, someone who is addicted to alcohol might deny having a drinking problem.

- Projection: Attributing one’s own unacceptable thoughts or feelings to someone else. For example, a person who is angry at their boss might accuse their boss of being angry at them.

- Displacement: Redirecting emotions or impulses from a threatening target to a safer one. For example, a person who is frustrated with their boss might go home and take out their frustration on their family.

- Regression: Reverting to behaviours characteristic of an earlier stage of development when faced with stress. For example, an adult might throw a temper tantrum when they don’t get their way.

- Sublimation: Channelling unacceptable impulses into socially acceptable activities. For example, someone with aggressive tendencies might take up a sport like boxing to channel their aggression.

- Rationalisation: Justifying behaviours or feelings with seemingly logical reasons, even if these are not the true reasons. For example, a student who fails an exam might blame the difficulty of the questions rather than their lack of preparation.

- Reaction formation: Acting in a way that is opposite to one’s unacceptable impulses. For example, a person who feels insecure about their masculinity might act overly macho.

- Introjection: Internalising the beliefs and values of another person. For example, a child might adopt the attitudes of their parents.

- Identification with the aggressor: Adopting the characteristics of someone who is perceived as threatening. For example, a victim of bullying might start to bully others.

Klein (1946) proposed an additional defence mechanism known as projective identification. This is regarded as a more primitive form of defence and is the process whereby individuals project unwanted parts of themselves onto others and then interact with those others as if they embody those projected parts. This process goes beyond projection in general where an individual transfers thoughts and feelings onto another. In projective identification an additional step is taken wherein the individual tries to recruit the other person into the beliefs and feelings projected onto them without being aware that these thoughts and feelings are part of themselves. Projective identification occurs when healthy psychological development is in some way blocked or limited and can be highly disruptive in close and intimate relationships.

Donald Winnicott

Donald Winnicott is another significant theorist who contributed to what may be regarded as modern-day psychodynamics. As a contemporary of Fairbairn, Klein and Anna Freud, and as both a paediatrician and psychotherapist, he appreciated the profound impact that developmental experiences have on children in their formation of the self and the movement towards adulthood. Like others from the British Object Relations School, he understood that we all interpret our relational experiences idiosyncratically constructing internal representations of the self, others, and world. Winnicott (1965) believed there is a nascent genuine or true self that experiences life and that this true self, in the process of constructing a mature functioning self, protects itself through various defences which he believed formed a type of false self. This double-self representation is best pictured as a seed kernel of the true self surrounded by a protective husk of the false self. To help us manage difficult emotional experiences Winnicott thought that we present to the world a self that is not always genuine. This false self emerges to protect the true self but in so doing confuses which self is the genuine self. When the individual struggles to connect with their true desires and emotions it results in a sense of disconnection from their authentic or true self. While living authentically out of the true self is a life-long challenge, it is particularly salient in teenage and early adulthood when the task of establishing one’s identity is central.

Another seminal contribution of Winnicott is the concept of the ‘good enough mother’. This idea might well be widened to refer to the ‘good enough parent’ or carer, but Winnicott did particularly denote the essential place of the mother’s care, especially in the early months of life. Focusing on the importance of nurture and the provision of a safe environment, Winnicott highlighted that if the infant experienced attuned relational care as well as functional care as in appropriate feeding and hygiene, they would experience the world as a warm and inviting place. He referred to this caring provision as the ‘holding environment’. Parents and carers are responsible to provide an environment in which both the psychological and physical needs of the child are provided responsively according to the child’s developmental stage. Some form of a holding environment is provided by parents until the child transitions into adulthood. In the early months of life, this provision of care and nurture is particularly dependent on eye contact, and on the touch and smell of the mother. Winnicott noted however, that while this was essential for effective nurture, it did not imply that the mother or primary carers had to provide this care perfectly. Hence, as long as care in all its various forms was consistently provided, albeit imperfectly, the child would feel safe and loved. This is the notion of the ‘good enough mother’.

It is important to remember that in the period that Winnicott was writing there was still a strong cultural influence on views about psychological health reflective of Freud’s more deterministic perspective about the influence of the unconscious. Winnicott was to some degree countering this overemphasis by implying that yes, we are influenced by our experiences, which may be registered in the unconscious, but a ‘good enough’ nurturing environment was really all that was needed. This view was not only refreshing but also had clear implications for the practice of psychotherapy. A therapist in this view does need to provide a safe ‘holding environment’ but cannot do so perfectly or provide a faultless response to a client’s/patient’s needs.

Stephen Mitchell

The progressive development of psychodynamic theory reached a seminal moment in the work of Stephen Mitchell. Building on the work preceding him, Mitchell (1988) highlighted the importance of relationship over drives in what he referred to as the ‘relational matrix’. Essential to this is the view that personality and psychopathology are shaped by early formative relationships. Mitchell reasoned that if relationships are fundamental in the formation of the self, then it is relationships that will provide the ground for healing. This view had significant implications for practice and was a departure from the classical approach that viewed the therapist as a neutral observer. Mitchell saw the therapist as an active participant in the therapeutic process, co-creating the therapeutic experience with the client.

This shift towards a much more relational approach encouraged therapists to be more attuned to the relational dynamics within therapy. It involved recognising and addressing the ways in which both the therapist’s and client’s histories and relational patterns influence the therapeutic process. Mitchell’s approach highlighted the importance of authenticity and mutuality in the therapeutic relationship and the need for emotional presence.

Robert Hobson and Russell Meares

Two psychiatrists one from the United Kingdom, Robert Hobson, and one from Australia, Russell Meares, became dissatisfied with the psychanalytic approach dominant at the time they were working together in the 1960s. Much of their work was with highly dysfunctional patients, many of whom today would be diagnosed as having borderline personality disorder. Drawing on a breadth of theory including Freud’s psychoanalysis, the self-psychology of Heinz Kohut, the client-centred therapy of Carl Rogers, and Carl Jung’s analytic psychology, Hobson highlighted the essential place of the therapeutic relationship and of emotional experience. Hobson initially developed what became known as the ‘Conversational Model’ also called psychodynamic interpersonal therapy (PIT) by analysing recordings of counselling sessions (Hobson, 1985; Guthrie, 1999). In these recordings he observed that the patient’s sense of self could either flourish or deteriorate within the counselling session. He represented these fluctuating experiences by the term ‘form of feeling’. Hobson noted that within the micro-moments of a relational interchange, the feeling experience or ‘form of feeling’ was ever changing and dynamic. He noted that part of this movement was influenced by how responsive the therapist was to the client’s experience in the moment. For example, a misaligned response, wherein the therapist communicated inadvertently that they did not understand or appreciate the client’s narrative or emotional state, tended to result in a negative shift in the ‘form of feeling’.

The ’form of feeling’ was also related to what is sometimes referred to as the ‘intersubjective field’ or ‘therapeutic third’. This is the concept of the ‘space between’ the therapist and client. Each interlocutor brings their own histories and experiences to a meeting, but in the meeting, it is also recognised that there is a third entity: that is the feeling in the room, the energy or space between each person. Hobson highlighted the significance of the interrelationship between each person’s ‘form of feeling’ and its relationship to the ‘therapeutic third’. In recognising this powerful dynamic Hobson coined the term ‘aloneness-togetherness’. This dialectic highlights the balance between individuality and relational connectedness. The central idea of the approach is to foster the client’s sense of personal being by encouraging a form of conversational relating that allows them to feel seen, accepted, and understood.

The focus of therapy for Meares and Hobson is the experiencing self within the micro-moments of therapy. Priority is placed on the therapeutic relationship for it is the relationship that provides a corrective emotional experience, fostering the development of a more cohesive and resilient self. Meares (2005) highlights the fact that if the self emerges in childhood through an experience of play in a safely attached environment, it is also through play that the adult self is healed. By play he is referring to the freedom to move between inner-world speech of metaphor, dreams, and association, and outer-world social speech focused on communication, allowing the ‘felt sense’ of one’s body and emotions to be encountered in new ways. Meare’s book, ‘The Metaphor of Play’ expresses the profundity of self-discovery especially as it is mediated through somatic and emotional engagement in the presence of an attuned other.

Martha Stark

Martha Stark is an American psychiatrist and psychodynamic psychotherapist who has written extensively on the development of psychodynamic therapy with a view to providing an integrative framework for the various contributions to the field. Stark highlights that each stage of the development of psychodynamic theory has provided a new insight and way of working, enriching the whole field. She identifies three broad stages of this development referring to them as three models of therapeutic action (Stark, 1999).

- Classical Psychoanalytic Theory

- Self-Psychology and Deficit Theories

- Contemporary Relational Theories

Each model, while having much in common, has a different therapeutic focus. Classical psychoanalysis aims is to promote understanding of intrapsychic conflicts and facilitate insight into the working of one’s inner world. This is largely brought about by gaining insight into one’s inner conflicts. It is not uncommon in this approach for the client and therapist to spend many sessions exploring the client’s history and internal struggles, especially as expressed in the form of defence mechanisms, with the therapist providing an interpretation of their meaning. The task of the therapist in this approach is to act as an observer and interpreter or analyser, hence the term analyst, of the client’s internal struggles. Stark refers to this approach as a one-person therapy as the therapist classically is understood to be a neutral observer.

In what Stark refers to as the deficit models, the focus is on what clients did not gain or achieve in their developmental years and thus are still seeking. For example, a person who did not receive warmth, care and loving attention in their family is likely to still be seeking such relational care and loving support in adulthood. While this, of course, is a natural desire throughout the life span, the relentless drive to gain such care is likely to result in dysfunctional expectations of primary others, negatively affecting relationships. Stark refers to Heinz Kohut’s Self Psychology as an exemplar of this approach. Kohut argued that what the narcissistic client did not receive was empathic and loving recognition in their developmental years and hence in adulthood is still seeking such personal affirmation. The lack of normal developmental recognition and support can result in a narcissistic personality formation wherein the individual develops a grandiose self and tries to manage their need for recognition through controlling and manipulative behaviour. Instead of focusing on analysis and interpretation, Kohut in such cases saw that the primary need was the provision of empathy and understanding so that the person progressively gained what was never received. This is not to say that the only goal of therapy in this view is to fill the void of insufficient developmental care. An important focus in the approach is to provide enough empathy and care so that the person is supported to grieve that which was never gained. In this respect, the focus is on empathic care so that the person is able to move through the grieving process to acceptance. Stark refers to the deficit models as one-and-a-half-person therapy. This is because unlike the classical analyst, the therapist is much more relationally involved in the therapeutic process. They allow themselves to feel the client’s pains and struggles and offer empathic support. However, the therapist is still in the expert position in which they do not share their own self.

The most recent developments in psychodynamic therapy are the relational theories. The notable turn in this direction came with the work of Stephen Mitchell and is also central to the Conversational Model developed by Hobson and Meares, the mentalization based therapy of Bateman and Fonagy (2016) and other modern dynamic approaches. In this different expression of relational theory, the therapist not only seeks to understand the client’s internal world and to provide some measure of repair to client deficits but also participates as a ‘real person’ who not only presents their expertise but also themselves as a person. This approach, similar to the expression of the therapist self in humanistic therapies, prioritises a genuine encounter between therapist and client. The therapist allows themselves to be ‘affected’ by the client, to empathically enter the client’s world not just for the purpose of appreciation of the other but also for the purpose of a genuine meeting between two people, a two-person therapy. According to Stark, the focus of therapy in the relational approach is to work with client enactments with a view to relational detoxification. When a client is presented with a genuine two-person encounter, it is more likely over time that their unresolved inner dynamics will emerge within the relationship. Here we are likely to see such defences as transference and projective identification play out in therapy. Within the dynamics of the relationship, the therapist will be at times the object of projection and therefore be affected by the client’s expectations. A skilful therapist will be able to work with the client to relationally process such psychic material enabling a detoxification of unresolved dynamics.

Implications for Practice

A central feature of all psychodynamic approaches is use of the therapist’s self, mediated through the therapeutic relationship. There is less focus on interventions as objective strategies like developing a thought record as in CBT or employing two-chair work as in gestalt therapy, for example. Generally, the intervention is the relationship itself. This is not to say that there are not key processes attended to by the therapist. Psychodynamic therapies predominantly share the importance of working with transference and counter-transference, facilitating emerging insights about intrapersonal and interpersonal dynamics, providing new and corrective emotional experiences via the provision of experiences not previously gained, and through processing enacted interpersonal dynamics (patterns) through a real two-person encounter. Therapists who employ modern interpersonal psychodynamic therapy integrate the three models outlined by Stark to meet the need of the individual client. As Martha Stark (1999) expresses it, “Armed with what she has come to know about the patient by way of listening to her, the therapist will intervene in a manner that involves either (1) enhancement of knowledge, (2) provision of experience, or (3) engagement in relationship as the primary therapeutic modality” (p. 236).

An interpersonal psychodynamic therapist would commonly work with clients by:

- joining with the client in a two-person encounter

- working in the here-and now while being aware of past developmental experiences

- attending to micro-moments especially shifts in emotional and somatic expression and follow these where they may lead

- reflecting these shifts to the client sensitively in a well-timed manner

- acknowledging changes in the relational dynamic in the room (e.g., transferential moments, defences, immediacy)

- encouraging the client’s discovery of insights and new meanings in a shared co-discovery.

Thinking About Skills

Given the focus of the therapeutic relationship in psychodynamic therapy it is obvious that active listening is a central capacity required of therapists. Training in communication microskills common to much of counsellor education is less prominent in standard psychodynamic programs. This is not to say that microskills are not valued. Traditionally, the emphasis on listening and interpretation have implied the use of microskills and assumed that such skills were part of the counsellor’s repertoire. Listening skills such as paraphrasing and summarising are essential to any deep listening encounter. Obviously other skills such as questioning and focusing are used in psychodynamic therapy as well. A microskill which does have prominence in psychodynamic therapy is ‘immediacy’ due to the importance placed on the relationship as the principal site of therapeutic action. Immediacy refers, first, to the ability to attend to and become aware of the dynamic in the room and within each person, and secondly, to be able to share this awareness. Immediacy may focus on either positive or negative experiences. For example, a counsellor recognising a sense of stuckness in the counselling process might say, “While we’ve been working well on key issues over the past weeks, I feel like today we’re a bit stuck and somewhat frustrated. I’m wondering if you feel that too?” This type of communication represents a genuine two-person relationship and much less one where the therapist takes an expert position.

The skill commonly referred to as ‘reflection of feeling’ has an important place in modern interpersonal psychodynamics. In counselling and psychotherapy we distinguish between emotions and feelings. Emotions are understood to be the more comprehensive aspect of human functioning related to somatic states including the chemistry that produces emotion, while feelings tend to refer to that aspect of our emotional and somatic states of which we become aware. Hence, our body, for example, might be in a state of anger involving such factors as increased muscle tension and cortisol production, the narrowing of peripheral vision, and increased hearing acuity, yet we may be largely unaware of feeling angry. Reflection of feeling and more broadly the reflection of somatic states is an important skill as cognition is always linked to emotion. It would be correct to say that we think what we feel. It is often the case that we only become aware of our cognitions and the related meanings we attach to them when we become aware of our feelings. Hence, the ability to attend to emotional and somatic states and to offer well timed reflection of these to clients is a key aspect of the therapeutic process.

Another central skill that is well represented in psychodynamic approaches is the ‘reflection of meaning’. A reflection of meaning is a tentative recognition of what new awareness is emerging within the conversation. This is different from providing or asserting a particular explanation of the client’s intrapersonal or interpersonal experience (interpretation). Rather, a reflection of meaning is the skill of reflecting back to the client what they are presently discovering. A reflection of meaning offered by the therapist helps the client to ground and clarify that which is already arising in client awareness.

In sum, the ability to apply the full scope of communication microskills is essential to any effective therapy and as such is an important foundation for the psychodynamically informed counsellor.

Questions for Reflection

References

Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2016). Mentalization-based treatment for personality disorders: A practical guide. Oxford University Press.

Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1944). Endopsychic structure considered in terms of object-relationships. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 25(1), 70-92.

Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1952). Psychoanalytic studies of the personality. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id. Hogarth Press.

Guthrie, E. (1999). Psychodynamic interpersonal therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 5(2), 135-145. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.5.2.135

Hobson, R. F. (1985). Forms of feeling: The heart of psychotherapy. Tavistock Publications.

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. In J. Mitchell (Ed.), The selected Melanie Klein (pp. 176-200). Free Press.

Meares, R. (2005). The metaphor of play: Origin and breakdown of personal being (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Mitchell, S. A. (1988). Relational concepts in psychoanalysis: An integration. Harvard University Press.

Stark, M. (1999). Modes of therapeutic action. Jason Aronson.

Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment: Studies in the theory of emotional development. International Universities Press.