8 Systemic Perspectives

Michael Ellwood

“Every person’s map of the world is as unique as their thumbprint” – Milton H. Erickson

“Without context words and actions have no meaning at all” – Gregory Bateson (1979, p. 15)

Key Takeaways

- The evolution of systems thinking opened new lines of therapeutic thought and intervention beyond individual and intrapsychic perspectives on problems and wellbeing, and has significant implications for counsellors working not just with families but with individuals and other groups.

- Key ideas in systems thinking includes an awareness of circular and mutual causality as opposed to simpler linear causality; the importance of context when understanding clients’ worlds; and the ability to explore and understand the multitude of systems that clients exist within.

- Practical applications of understanding systemic perspectives include grasping the key distinction between first-order and second-order change; shifting from a focus weighted on ‘content’ and into an understanding of and attention to ‘process’, both in clients’ stories as well as in the here-and-now in the counselling room; and the application of circular questioning as a means to introduce new information into systems.

- Context is key! Understanding broader context, regarding clients’ presenting concerns and worldviews as well as regarding the counselling engagement itself, allows for a more holistic and accurate understanding of what clients are struggling with as well as developing the most appropriate therapeutic fit.

Introduction

So far in this text you have encountered concepts and processes with a particular focus on individual counselling. This chapter will expand this focus to explore broader systemic perspectives and concepts that hold further valuable understanding to your work with clients, regardless of whether you are working with individuals, couples, families or even groups. In particular this chapter will explore the underpinnings of some of these perspectives, namely systems theory and cybernetics, and the varying ways in which these principles have been adapted into therapeutic practice over time. From there you will develop an understanding of systemic practices and skills that can be utilised more generally, regardless of which specific counselling approach or modality you may be working from. Reflections at the end of the chapter will also encourage you to consider how shifts from individual to systemic paradigms may change the ways in which you conceptualise client struggles, as well as how you may find ways of working more holistically and incorporating the varying systems within which clients exist.

Cybernetics

The term cybernetics is derived from the Greek word ‘kybernetes’, meaning ‘steersman’, and was coined by Norbert Weiner (1948) as a means to describe systems that regulate themselves through feedback loops. While this study of systems was originally conducted by a multidisciplinary group of researchers including mathematicians, physicians, economists, psychologists, engineers and sociologists, its concepts were later introduced more directly into the therapeutic realm by Gregory Bateson (as discussed shortly). This original research, tied quite closely to the events and context of the Second World War, explored not only system organisation and processes but also patterns of communication, and was curious about comparisons between inorganic (material) and living systems, particularly in attempting to better understand complex systems.

General Systems Theory

Around the same time as Weiner and colleagues were exploring the workings of complex systems, Ludwig von Bertalanffy, a biologist in Vienna, was exploring a better understanding of organic systems and their ability to thrive (or not) based on their connections to their environment (1934, 1969). von Bertalanffy’s described his later work as general systems theory (1969), in an attempt to develop a universal theory for all living systems. This research particularly focused on organic systems as open systems – systems that relate with the environment around them, including the ability to adapt to environmental changes, as well as containing more complex interactions between parts of the system itself as well as conditions outside of the system. These concepts were later applied more directly to human relationships – particularly families – as following the same set of systemic principles as other organic systems.

Introduction into Therapy

The link between the broader systems theory world and the therapeutic world was first made in 1946 by Gregory Bateson, an anthropologist and ethnologist, who was more broadly interested in epistemology (the study of the grounds of knowledge). First coming across the influential works of Weiner, along with other cybernetics colleagues Rosenblueth and Bigelow, at the 1942 Macy Conference, as well as being formally introduced to the ideas of Milton Erickson, Bateson later returned to the 1946 Macy Conference to present the first of what turned out to be many presentations and papers attempting to articulate a more adequate framework for social sciences, and further bridging the gap between the physical and behavioural sciences. During this time, Bateson joined Juergen Ruesch as a research associate in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California Medical School, and over the next several years began to further clarify his ideas into a theory of human communication (Heims, 1977). Interestingly, it can be noted that the term cybernetics was more commonly used within European circles, while in the United States language around systems theory was more broadly used (Bateson & Mead, 1976). Bateson again proved to be a crucial figure in bringing together these varied streams of thought (along with others such as Von Neumann and Craik) into a more coherent and unified theoretical framework exploring communication problems along with “the problem of what sort of a thing is an organized system” (Bateson, 1972, pp. 474-475).

In 1953, Bateson was joined by colleagues Jay Haley, John Weakland and William Fry as part of a research project exploring the role of paradoxes of abstraction in communication. The team was joined by Don Jackson, a psychiatrist, in 1954 as part of a new research project exploring schizophrenic communication, and it was this project in particular that led to the famed “double bind hypothesis” (Bateson et al., 1956) – hypothesizing a shift in thinking around understanding schizophrenia as an interpersonal, relational phenomena rather than purely an intrapsychic disorder of the individual. While later argued to be incomplete if not inaccurate, the theory proved to be a milestone in developing broader systemic understanding of what had previously held to be individualistic perspectives on mental health, families and communication. Indeed, members of this original research team went on to form the Mental Research Institute (MRI) in Palo Alto, along with others such as Virginia Satir, Richard Fisch and Paul Watzlawick. Don Jackson, argued to be one of the most prolific authors within family therapy (Foley, 1974), joined along with Nathan Ackerman in 1962 to establish one of the most recognised and prestigious journals in the field, Family Process. During this time, the field of family therapy began to flourish in multiple theoretical directions, with therapists and researchers such as Salvador Minuchin, Nathan Ackerman, Virginia Satir, Jay Haley and Murray Bowen beginning to articulate their own understandings and theories of families and systemic processes in more concrete ways.

Key Principles

Circular Causality

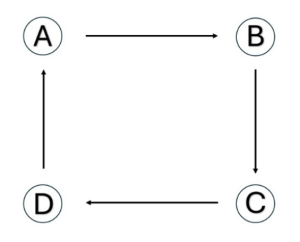

One of the fundamental shifts in thinking within systems theory is a movement away from ideas of linear causality (A causes B causes C; Figure 1) and into ideas of circular causality (A influences B which influences C which influences D, which in turn influences A; Figure 2).

Figure 1. Linear Causality

Figure 2. Circular Causality

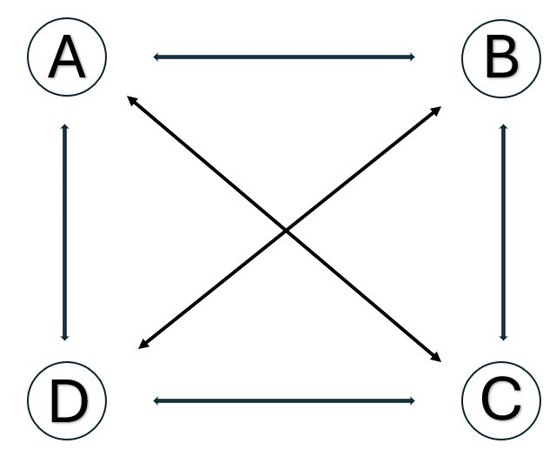

In more specific nuances, one can also view all elements as influencing each other rather than a more simplistic circular demonstration (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Mutual Causality

Becvar and Becvar (2014) discuss the linear causality perspective as a traditional Lockean, scientific view of the world, where one can trace particular events back to a singular cause, while a cybernetics or systems view of circular causality instead focuses on reciprocity and shared responsibility, showing less interest in why something happened and greater interest in what is going on (p. 10). While not without its own implicit limitations (later criticisms highlight the justifiable concerns around suggesting equal or shared responsibility within a family system within contexts such as family violence or abuse), this paradigm shift is still an important shift away from earlier intrapsychic and individualistic views of problem formation, and into a more open conceptualisation of interconnectivity and relational influences.

Context

A simple definition of context is a set of facts or circumstances that surrounds a situation and helps understand it. This brief explanation, however, does not do justice to the profound importance of the idea of context within the field of counselling and psychotherapy – indeed, as the popular maxim goes, “Context is king!” This notion becomes considerably more relevant when exploring the paradigm shift from individual perspectives to systemic and relational lenses. Bradford Keeney (1988) states that “the shock of family therapy involved its proposal that individuals be seen as principally organized by their social contexts” (p. 101), reflecting the change from viewing individual psychopathology as purely intrapsychic to a phenomenon marked by social and relational influences and cues. While the first identification of the role of context within counselling and psychotherapy is more difficult to determine, it was perhaps Watzlawick et al. (1967) who first discussed the role and importance of environment and relationship in their text Pragmatics of Human Communication, through reflecting:

… a phenomenon remains unexplainable as long as the range of observation is not wide enough to include the context in which the phenomenon occurs. … If a person exhibiting disturbed behaviour (psychopathology) is studied in isolation then the inquiry must be concerned with the nature of the condition and, in a wider sense, with the nature of the human mind. If the limits of the inquiry are extended to include the effects of this behaviour on others, their reactions to it, and the context in which all of this takes place, the focus shifts from the artificially isolated monad to the relationship between the parts of a wider system. The observer of human behaviour then turns from an inferential study of the mind to the study of the observable manifestations of relationship (p. 21).

Gregory Bateson (1991) offered a broader set of ideas about context in identifying that “no message or message element – no event or object – has meaning or significance of any kind when totally and inconceivable stripped of context” (p. 143). O’Hanlon and Wilk (1987) furthered this perspective in arguing that reality is always necessarily contextual (p. 183), and that what a thing ‘is’ always depends on the context in which it is found (p. 183).

In summing up these notions, we can therefore logically infer that it is important to consider the surrounding circumstances, environment, and relationships to better understand the unique nature and meaning of a phenomenon or experience for the individual involved. Context is, indeed, king.

Ecological Systems Theory

Originally proposed as a theory of child development, Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (1977; later revised to a bioecological model by Bronfenbrenner in 1994) was an early example of a shift from an individual and intrapsychic understanding of child development, into a broader systemic understanding of the different environmental and systemic influences on individual development. While originally suggested specifically as a model of child development, the model has broader applications when considering systemic influences on both individuals and broader relational systems. The model suggests five nested systems – the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem and chronosystem – that extend out in order of impact, and are interrelated and mutually influence each other.

Figure 4. Ecological Systems Theory

The microsystem involves the most immediate relationships and systems surrounding the individual, such as family, peers, work or school, religious community, and the like. These relationships are also seen to be bi-directional with the individual, mutually influencing each other.

The mesosystem is viewed as the interactions between two or more microsystems at the first layer, thus making up a mesosystem – examples may include family systems that are also actively involved with school systems.

Exosystems can be seen as broader social structures that do not necessarily interact directly with the individual but can be seen as influencing the microsystems – these involve larger systems such as government, educational systems, legal or political systems.

The macrosystem reflects less concrete structures than the earlier layers, but rather the broader social conditions surrounding the other systemic levels. This can also be seen as a layer that is less specific to one individual, but rather sitting across multiple individuals within a particular society and culture. This layer involves aspects such as social norms, cultural values and attitudes, and beliefs and ideas regarding elements such as gender roles, family structure and social issues.

Sometimes seen as a broader nested level and other times depicted as a separate layer (as depicted in Figure 4), the chronosystem depicts the shifts and transitions over time, recognising distinctions between predicted or unpredicted changes across time, as well as the ways in which other systemic layers change or are influenced over time.

Taken as a whole, the ecological systems model demonstrates a broader systemic understanding of the various influences on the individual client, while this can also be extended to consider the different levels of context surrounding couples, families, communities and beyond. As discussed later in this chapter, this also lends itself to the different considerations about how we can best explore the different contexts in which our client exists and that may relate to their presenting concerns, rather than conceptualising clients as individuals in isolation.

Change – First-order and Second-order

Acknowledging that taking a systemic perspective involves shifting beyond individual paradigms and into broader relational and contextual view of the world, this paradigm shift also extends to different understandings of change itself. This can be defined as a distinction between first-order and second-order change (Watzlawick et al., 1974). The concept of first-order change, such as exploring individual behaviour change within any particular system or context, makes sense from a perspective of linear causality – if we can trace a problem back to some origin or cause and create change at this point, the problem therefore becomes eliminated. Often being a more superficial change, such as changing the timing of an event, the success of this level of change depends on context. If this involves shifting the timing of a meal due to a change in schedule, then this can be an appropriate level of change within a family or relationship system. Postponing an argument until a later time, however, provides less relief for the system. It is at this point that second-order change becomes relevant.

If first-order change is considered to be change within a system, such as changing individual behaviour or creating a superficial change, then second-order change can be considered as a change to the system itself. Again, depending on context this can take different forms. Using the examples above, while shifting the time of a meal due to a change in family members’ schedules may be effective in and of itself, a second-order level of change might involve changing who prepares meals, or even a change to the expectation of everyone sitting down for meals at the same time. In a more significant example, while we can clearly identify that shifting the time of an argument provides a less effective solution to the argument itself, a second-order change might involve addressing the pattern of arguments themselves, such a sitting down with a counsellor or therapist, or at least having a different type of conversation about the recurrence of conflict.

In this sense, second-order change is often also referred to as meta-change, or a “change of change” (Watzlawick et al., 1974, p. 11). This can mean changing the rules of a system, redefining the structure or hierarchy of a family, or having conversations about conversations (talking about the way we talk). As we will explore in the following section, this also signifies an important shift in the therapeutic focus from content and into process.

Implications for Practice

Content vs Process

One way in which the shift from linear to circular causality applies more concretely in practice is a change to a lesser focus on content and a greater focus on process. This can present in different ways depending on the context and nature of the counselling setup. (See also the earlier exploration of similar ideas in chapter 5).

Individuals may commonly present with the ‘facts’ of their problem or concern, including a history of how this has developed, possibly ideas about the cause or origin, and/or a view of how they would like problem resolution to look like. Large parts of this might be viewed under the banner of content – the facts, the details, the cause, and the desired outcome. While this is still highly relevant to the counselling process, a systemically-minded counsellor will also be curious about processes underlying this content – when this problem was occurring, what was the context in which it was occurring? What were you doing or not doing? How did this impact you during and after? Were others influenced by or influencing this situation? As you are telling this story now, what do you notice as you tell it? How are you experiencing the re-telling in the present moment? Within this desired future or outcome, how will you notice that things are different? What will you be thinking or doing differently? These questions – and other variations on the theme – might be asked explicitly, or they may be more internal curiosities on the part of the counsellor while exploring the story.

In family or relationship settings, along with the aforementioned ways of thinking, the counsellor is also intensely interested in the here-and-now dynamics of the clients in the room. As one client is speaking, how are others reacting to these discussions? What physical or non-verbal dynamics are playing out in the room? As clients speak with each other, how are they speaking with each other? Are there patterns or themes to their way of communicating? Along with what is being said, what is not being said (the absent but implicit)? As potentially new information or perspectives are shared by different members of the family or relationship, does this lead to shifts in thinking or feeling within other family members (news of a difference that makes a difference)? This extends to a curiosity about the clients’ experiences of the concern outside of the counselling room as well – rather than simply what was said within conflict, how was it said? What led up to the experience, and what occurred afterwards? What was each client’s experience of that event? Who did what to whom and in what way?

A practical example of this content-process distinction lies within the standard couple therapy assessment process in the Gottman couple therapy method (Gottman & Gottman, 2015). During the initial interview with the couple, the counsellor explores milestones and experiences across the couple’s relationship history. As these experiences are discussed, the counsellor is paying attention not only to the content of these experiences, but also to the ways in which the couple experiences the re-telling together, as potential indicators of dynamics in their relationship – do they smile fondly at each other and laugh at enjoyably memories? Do they challenge or contradict each other in the details of their stories? Are they closed off and non-responsive to each other as each partner shares their experiences? These observations of process provide a greater depth of insight into the couple’s relationship as they experience it in the moment.

Exploring Context

Building on the ideas posed earlier regarding broader systemic understanding of the client’s world and environment, several practice considerations can be explored here. Firstly, the importance of exploring and understanding the wider contexts in which the client and their concern exists cannot be overstated. Apart from allowing a deeper and more empathic understanding of the client’s experiences and current circumstances, an exploration of the wider contexts, such as that suggested by Bronfenbrenner earlier in this chapter, can also create a difference in the way a concern is conceptualised. A simple example here involves a child client who has been referred with concerns around concentration and behavioural challenges at school. An individual and intrapsychic exploration alone may lead to hypotheses and assessments around neurodivergence and possibilities such as ADHD or ASD diagnoses. Zooming out and exploring the broader contexts around the child may reveal greater difficulties in the home environment such as domestic and family violence, high conflict separation, significant physical or mental health concerns for another family member, or abuse or neglect of the child themselves. Taken in this context, the difficulties at school now may be viewed differently, potentially as a symptom of larger systemic or relational challenges in the child’s life rather than problems isolated within the child themselves.

We can also view this contextual understanding over time, such as differences in perception of the current situation by the client as compared to historic contexts. An example of this may be a client who presents with concerns about her relationship with her husband who she feels can be overly rigid in his approach to structure, routine and behaviours within the relationship. While some counsellors may quickly jump to questions around the sustainability of the relationship for the immediate client, an exploration of the client’s history may reveal early family and relationship experiences marked by significant violence, unpredictability, and a lack of affection or warmth. In comparison to these past experiences, the client may feel this current relationship to be markedly more reliable and safer, despite the concerns around rigidity and rules, and may find that the prospect of ending this relationship generates fears of returning to a lack of warmth and care and an increase in unpredictability in their world. While this does not eliminate the need to still explore the present concerns, an understanding of the contrast between current and historic contexts generates a greater understanding of the client’s dilemma at this point in time.

This leads neatly into an acknowledgement of exploring context as a way of better understanding our client’s unique worldview and perspective on their concerns. This includes a clear understanding of the client’s intended or desired focus of the counselling work itself. While not the first to explore such ideas, Erickson (1980) proposed the use of what he called utilization – “exploring a patient’s individuality to ascertain what life learnings, experiences and mental skills are available to deal with the problem … [and] then utilizing these uniquely personal internal responses to achieve therapeutic goals” (Erickson & Rossi, 1979, p. 1). This concept was further built upon by the Mental Research Institute (MRI) in exploring the idea of position – the client’s worldview and beliefs that influence both the presenting problem itself as well as the client’s engagement in therapy (Watzlawick et al., 1974). In more recent decades this has evolved in conversations and acknowledgement of what Duncan et al. (2004) refer to as the client’s theory of change – seeing the client worldview as the determining theory for therapy (Duncan et al., 1997). This exploration and acknowledgement of how clients perceive and make sense of their lives and their presenting concerns creates opportunities for the building of a strong alliance, clearer and more meaningful goal-setting in line with the client’s identified desired direction and outcomes, and a strong alignment of strategy and intervention with the client’s systemic contexts as well as their unique understanding of their lives and the world around them.

The last important consideration is an understanding of context when it comes to the counselling work itself. Far from being irrelevant, the environment and systems within which counselling takes place can have far-reaching implications for the nature and focus of the work itself. Consider the contextual distinctions between clients attending counselling within an organisational disciplinary process, a mandated therapeutic engagement within a correctional facility or context, a school setting as a result of behavioural concerns in a classroom, and a minimally funded organisation offering short-term counselling support around a limited range of presenting concerns. Simply put, in settings other than privately funded counselling practices, the potential is much higher for different agendas to be in play other than the immediate wellbeing of the client or their own desired focus for therapeutic work. Thus, this context needs to be acknowledged and incorporated at least in some ways into the goals and focus of the therapeutic work – ignoring these broader contextual requirements and agendas can threaten the viability of maintaining support for the client and risk broader relationships; while ignoring the presenting needs as identified by the client themselves risks a rupture to the therapeutic relationship and an ignoring of the client’s own worldview and desired outcomes.

This understanding of the broader contexts and agendas for the therapeutic work also extends to the way in which the client perceives these contexts; Do they align with these larger agendas and goals or does this pose a dilemma or tension around the focus of the work? Does the client view this therapeutic offering as being helpful and desired, or is there a sense of coercion or mandating of the engagement? Are there concerns about how the client may be perceived by others as a result of attending counselling? Within the current social and political environment for counselling practice, these are vital considerations that counsellors must keep in mind when considering the larger context of their therapeutic work.

Circular Questioning

Originating in Italy in the 1970s, the Milan Associates (Mara Selvini Palazzoli, Luigi Boscolo, Gianfranco Cecchin and Guiliana Prata) developed a model of systemic family therapy inspired by the strategic work of the Mental Research Institute along with the systems theory and communication ideas of Gregory Bateson, with a particular focus on paradox/counter-paradox and circularity. The Milan Associates particularly viewed families as presenting to therapy with an inherent paradox, with an underlying message of “We have this (problematic member who must change) … but as a family we are fine … (and intend to remain unchanged)” (Tomm, 1984a, p. 115), implying an impasse of seeking both change and stability. Inherent to their approach was a focus in attention towards patterns of interaction rather than intrapsychic problems, viewing families as caught up in recursive and holistic patterns, and including perceiving therapists as being a part of the pattern they are observing. A key therapeutic practice emerging out of this systemic understanding was the use of circular questioning (Selvini Palazzoli et al., 1980; Penn, 1982; Tomm, 1987). This style of questioning draws back to the circular ideas of patterns within family relationships, as well as arguing that inviting other family members to share their perceptions of relationships between particular family members allows for a breaking of a rule that they believe operates in dysfunctional families: that family members should not comment on the relationship of other family members in their presence (Selvini Palazzoli et al., 1980).

The concept of circular questioning, therefore, invites new perspectives into the family almost as a soft reframe, rather than directly suggesting “Think about your family/family member in this particular way”, through the addition of potentially new information about how family relationships and behavioural patterns are experienced and perceived by others in the family. A key consideration when engaging in circular questioning is not to ask questions that we believe we (or the family) know the answer to – rather, the intention is to explore new information and perspectives for the family, keeping in mind the often-quoted proposition by Bateson that a bit or piece of information is “news of a difference that makes a difference” (Bateson, 1972, pp. 271-272). Selvini Palazzoli et al. similarly suggest that “1. Information is a difference. 2. Difference is a relationship (or a change in the relationship” (1980, p. 8). The precise types of circular questioning are quite varied in style and focus and have been articulated in different formats by various authors over time.

The Milan Associates (Selvini Palazzoli et al., 1980) originally suggested questions that focus on behavioural sequences and different family members’ interpretation of behaviours, such as ranking each other on specific behaviours (“On a scale of 1 to 10, how bad do you think the fighting was this week?”) or exploring hypothetical questions (“If you were to separate, which parent would the children want to live with?”). Penn (1982) suggested difference questions such as changes over time or between verbal and analogic information. Tomm (1984b; 1988) originally explored questions highlighting the spatial and temporal differences, and ultimately proposed four major types of questions linked to the theoretical assumptions and intention of the therapist: Lineal (problem definition/explanation); Circular (difference questions); Strategic (leading and confrontational); and Reflexive (hypothetical or observer perspective). As the types and styles of circular questioning can feel confusing and difficult to understand to novice counsellors, Brown (1997) suggests an initial focus on creating distinctions and connections through circular-type questions as a simpler starting point, with more complex approaches to questioning developing over time and with experience.

Reflective Questions

References

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. Ballantine.

Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and nature: A necessary unity. Dutton.

Bateson, G. (1991). A sacred unity: Further steps to an ecology of mind. Harper Collins.

Bateson, G., Jackson, D. D., Haley, J., & Weakland, J. (1956). Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Behavioral Science, 1, 251-264.

Bateson, G., & Mead, M. (1976). For god’s sake, Margaret. The CoEvolution Quarterly, Summer, 32-43.

Becvar, D. S., & Becvar, R. J. (2014). Family therapy: A systemic integration (Eighth ed). Pearson.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32 (7), 513.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Ceci, S. J. (1994). Nature-nurture reconceptualised: A bio-ecological model. Psychological Review, 10 (4), 568–586.

Brown, J. (1997). Circular questioning; An introductory guide. Australia & New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 18(2), 109-114.

Duncan, B., Hubble, M. A., & Miller, S. D. (1997). Psychotherapy with “impossible cases”: The efficient treatment of therapy veterans. Norton.

Duncan, B., Miller, S. D., & Sparks, J. A. (2004). The heroic client: A revolutionary way to improve effectiveness through client-directed, outcome-informed therapy. Jossey-Bass.

Erickson, M. H. (1980). The use of symptoms as an integral part of psychotherapy. In E. Rossi (Ed.), The collected papers of Milton H. Erickson on hypnosis (Vol. 4). Irvington.

Erickson, M. H., & Rossi, E. L. (1979). Hypnotherapy: An exploratory casebook. Irvington.

Foley, V. D. (1974). An introduction to family therapy. Grune & Stratton.

Gottman, J. S., & Gottman, J. M. (2015). 10 principles for doing effective couples therapy. WW Norton & Company.

Heims, S. P. (1977). Gregory Bateson and the mathematicians: From interdisciplinary interaction to societal functions. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 13, 141-159.

Keeney, B. P. (1988). Autonomy in Dialogue. Irish Journal of Psychology, 9(1), 101–109.

O’Hanlon, W., & Wilk, J. (1987). Shifting contexts: The generation of effective psychotherapy. The Guilford Press.

Penn, P. (1982). Circular questioning. Family Process, 21(3), 267-280.

Selvini Palazzoli, M., Boscolo, L., Cecchin, G. & Prata, G. (1980). Hypothesising – Circularity – Neutrality: Three guidelines for the conductor of the session. Family Process, 19(1), 3-12.

Tomm, K. (1984a). One perspective on the Milan systemic approach: Part 1. Overview of development, theory and practice. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 10(2), 113-125.

Tomm, K. (1984b). One perspective on the Milan systemic approach: Part II. Description of session format, interviewing style and interventions. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 10(3), 253-271.

Tomm, K. (1987). Interventive interviewing: Part II. Reflexive questioning as a means to enable self-healing. Family Process, 26, 167-183.

Tomm, K. (1988). Interventive interviewing: Part III. Intending to ask lineal, circular, strategic or reflexive questions. Family Process, 27(1), 1-15.

von Bertalanffy, L. (1934). Wandlungen des biologischen Denkens. Neue jahrbücher für Wissenschaft und jugendbildung, 10, 339-366.

von Bertalanffy, L. (1969). General system theory: Foundations, development, applications. George Braziller.

Watzlawick, P., Weakland, J.H., & Fisch, R. (1974). Change: Principles of problem formation and problem resolution. Norton.

Weiner, N. (1948). Cybernetics. Scientific American, 179(5), 14-18.