12 Developing your research question

“The search question is the engine that drives” a search for and review of evidence to inform practice (Bronson & Davis, 2012, p. 16). Thus, attention to the process by which practice questions are formulated warrants attention.

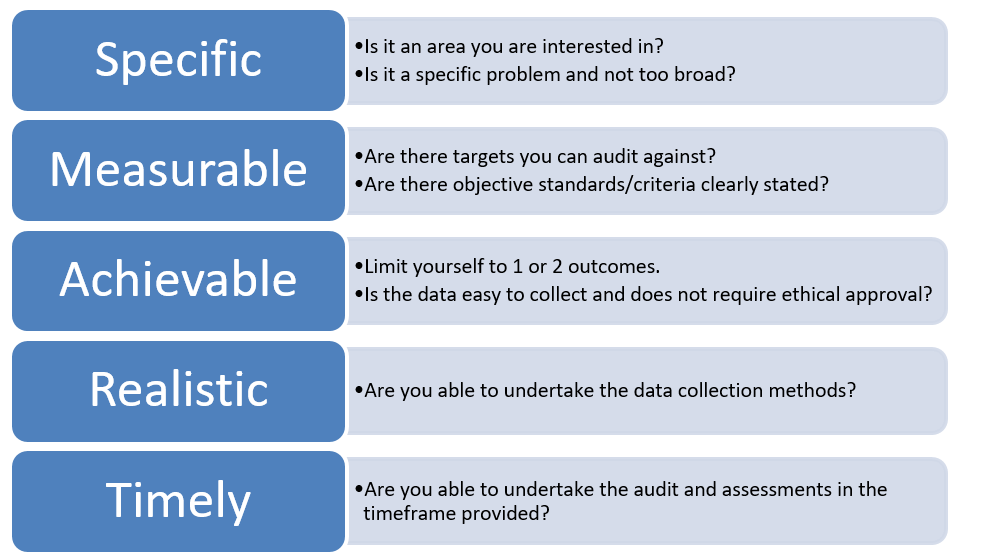

When considering your quality improvement project question reflect on the SMART goals approach. Carefully consider what is feasible is undertake within the timeframe of the project, does your idea require specific ethical considerations, and how will you obtain the information to address the questions you are considering.

Question formulation

The questions that drive a researchers search for evidence to inform practice decisions differ somewhat from the kind of questions that drive nurses and midwives to understand diverse populations, clinical problems, and experiences. These frameworks include:

- PICO (patient/population; intervention; comparison (if there is one) and outcomes)

- PEO (population, exposure and outcomes)

- PCC (population/problem, concept, context)

- SPIDER (sample; phenomena of interest; design; evaluation and research type).

When developing your research question, thoughtfully plan how you will answer it. Identify what is the necessary information to collect and determine the best way to present your findings. Continuously refer back to your research question to ensure your data collection methods, such as surveys, gathers the relevant information that directly addresses your question.

When developing your research question, thoughtfully plan how you will answer it. Identify what is the necessary information to collect and determine the best way to present your findings. Continuously refer back to your research question to ensure your data collection methods, such as surveys, gathers the relevant information that directly addresses your question.

Using the PICO framework to formulate the question

The PICO framework helps to focus your work and can refine your database searching. It is a part of the planning process that deserves your time and attention. Consider each of the following elements and provide as much detail as you can for each element.

The PICO framework comes from literature on evidence-based practice in medicine and nursing. This is demonstrated in its full name, the Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome framework. The PICO framework results in the comparison of two intervention options.

- Patient or population (or client or consumer) refers to specifically identifying the characteristics of the population around which the search for evidence is directed.

- Intervention requires specification of the interventions or other practice activities (e.g., type of assessment or clinical test, treatment, prevention, or policy) under consideration.

- Comparison is the act of comparing the intervention options identified in the prior step.

- Outcome refers to the goal or goals to be achieved by intervening.

“If an elder residing in a nursing home[Patient or population] participates in a pet therapy program[Intervention] or attends an adult day program[Comparison] which intervention will result in lower depression[Outcome]? (Heltzer, n.d., p. 2)

Using the PEO framework to formulate the question

The PEO framework can be beneficial when developing research questions relevant to quantitative data. The framework is based on three concepts: population, exposure and outcome.

Example: In infants, is there an association between exposure to soy milk and the subsequent development of peanut allergy (Levine et al., 2014)

- Population: infants (Can you refine this to an age group – newborns, one-year olds, children under one; what age is your focus?)

- Exposure: exposure to soy soymilk formulas, food?)

- Outcomes: peanut allergy (allergic reaction, rash, anaphylaxis, formal testing v reported testing; which is your focus?)

Using the PCC framework to formulate the question

The PCC approach is useful for broad questions such as those you might see in a scoping review, and focusses on population/problem, concept and context.

Example: The scoping review aims to identify in which domains of perioperative care nurses are leading experimental research (Munday et al., 2020).

- Population/problem: Perioperative nurses

- Concept: Leading experimental research

- Context: Domains

Using the SPIDER framework to formulate the question

When developing a research question for qualitative or mixed methods research the SPIDER, and is formulated based on sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation and research type.

Example: What are young parents’ experiences of attending antenatal education? (Cooke et al, 2012).

- Sample: young parents

- Phenomenon of interest: antenatal education

- Design: questionnaires, surveys, interviews (the means required to obtain the information to address the question)

- Evaluation: experiences

- Research type: qualitative mixed methods (the research design needed to address the developed research question).

Forming a guiding question for your intervention and evaluation

Example

Consider LGBTQ+ teens, research reports that LGBTQ teens are more at risk for depression when compared to non-LGBTQ+ teens (Russell, Ryan, Toomey, Diaz & Sanchez, 2011). Research also suggests that having a peer support system affects levels of depression amongst all teens in that age bracket (Pfeiffer, Heisler, Piette, Rogers & Valenstein, 2011). As a clinician in the high school, you want to offer an LGBTQ+ support group for several students you have been treating for depression. The PICO components of this identified social problem are:

P = Patient or Population: LGBTQ+ teens

I = Intervention: Support meetings and individual counselling

C = Comparison: Treatment as Usual (individual counselling)

O = Outcome Lower levels of reported depression as measured by Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS-R)

In the PICO process, we have identified the population as LGBTQ+ teenagers. After a careful review of the literature and/or a needs assessment, the intervention you decide to implement is a peer support group. If you wanted to evaluate the effectiveness of this program, you will want to compare LGBTQ+ teens that attend a peer support group and those who do not, and the outcome will guide the evaluation plan, measured by the Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS-R) (Mayes et al, 2010).

Types of research questions

Background vs foreground questions

In order to locate the most useful research, we must ask well-defined questions:

Background questions – the “forest” (broad in scope)

- seek general knowledge about a condition or thing

- provides basic information for a greater understanding of concepts; not intended for making a clinical decision about a specific patient

- typically found in textbooks, guidelines, point-of-care monographs.

- contain two essential components: Example: What causes migraines? or How often should women over the age of 40 have a mammogram?

- A question root (who, what, when, etc.) with a verb

- A disorder, test, treatment, or other aspect of healthcare.

Foreground questions – the “trees” (focused in scope)

- seek specific knowledge to inform clinical decisions or actions

- require a grasp of basic concepts to fully comprehend

- typically found in journals and conference proceedings

- contain 3-4 essential components (see PICO)

Typically used in evidence-based medicine, the PICO model is a useful way of formulating client, community, or policy-related research questions.

| P = Problem | How would I describe the problem, population, or patients? |

| I = Intervention | What main intervention, prognostic factor or exposure am I considering? |

| C = Comparison | Is there an alternative to compare with the intervention? |

| O = Outcome | What do I hope to accomplish, measure, improve or affect? |

Example PICO-based research questions

In patients with acute bronchitis, do antibiotics reduce sputum production, cough, or days off?

Among family members of patients undergoing diagnostic procedures, does standard care, listening to tranquil music, or audio-taped comedy routines make a difference in the reduction of reported anxiety?

Original PICO model by Richardson, W.S., et al (1995). The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP Journal Club, 123(3), A12-A13.

PICO examples

Here are two example clinical scenarios where the most important elements of the scenario have been identified using the PICO framework.

Example 1

Tom is 55 years old and has smoked one pack of cigarettes a day for the last 30 years. He is ready to quit, and is wondering about his options. He has heard of a medication called bupropion, but is also familiar with nicotine replacement therapy options such as patches, lozenges, and gum. Tom wants to know which option will work best to help him quit and abstain from smoking again in the future.

Patient/problem/population: mid-50s male with a 30 pack-year history of smoking

Intervention: bupropion

Comparison intervention: nicotine replacement therapy

Outcome: long-term abstinence from smoking

Example 2

Janet is 42 years old and just had her first mammogram. She does not have a history of breast cancer in her family, and she has heard from her friends that she doesn’t need to have a mammogram every year, only every three years because of new guidelines. She wants to know if she has to come back every year for a mammogram, or if she can make an appointment every three years.

Patient/problem/population: woman in her 40s with no family history of breast cancer

Intervention: mammograms every three years

Comparison: yearly mammograms

Outcome: early detection of breast cancer

Framing good questions

Once you’ve identified the core concepts of your topic using the PICO framework, how do you translate them into a question?

Describe the subject of the question

It may be helpful to phrase the question in this form: “How would I describe a group of patients similar to this one? What are the relevant characteristics?”

Define which intervention you are considering for the specific patient or population

It is sometimes helpful to name a second intervention with which to compare the first.

This might be another treatment, placebo, or ‘usual care.’

For example, diagnosis via a traditional X-ray is often compared to diagnosis with an MRI. However, it is not always necessary to include a comparison.

Define the type of outcome you wish to assess

There are many possible outcomes. Try to focus on patient-oriented outcomes like death, disability or discomfort. These could include mortality, disease progression, results of a diagnosis test, confidence/anxiety, cost effectiveness and more.

Let’s take a look at our PICO examples from before.

Example 1

Patient/problem/population: mid-50s male with a 30 pack-year history of smoking

Intervention: bupropion

Comparison intervention: nicotine replacement therapy

Outcome: long-term abstinence from smoking

A well-built clinical question for these PICO elements would be:

In a 55 year old man, would the administration of bupropion therapy versus nicotine replacement therapy lead to long-term abstinence from smoking?

Example 2

Patient/problem/population: woman in her 40s with no family history of breast cancer

Intervention: mammograms every three years

Comparison: yearly mammograms

Outcome: early detection of breast cancer

A well-built clinical question for these PICO elements would be:

In a 42 year old woman with no family history of breast cancer, are mammograms every three years as effective in detecting breast cancer as yearly mammograms?

Asking the right questions

It helps to get into a mind frame that will help you formulate your question and think deeply about how best to answer it through the research process. The most common way to frame a question is using PICO, which stands for Population/Problem (P), Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome. There are different ways of formulating a PICO question depending on what kind of patient or scenario a clinician seeks to address.

Using the questions

A well-formed question can help shape how a person locates information on a topic. It helps to understand who a clinician wants to help and why. Each part of a question forms a concept area, which can help form the basis for a search to locate literature on the topic in a database like PubMed.

PICO

PICO questions are one of the most used frameworks for asking clinical questions. It considers four main variables—a patient or population (P), an intervention for treatment, exposure, diagnosis, etc (I), a comparison for that intervention (C), and a desired outcome (O).

Framing a good clinical question will help a clinician or researcher develop a clear statement of intention and provide a means for focusing on their information needs, identifying crucial concepts in both the search and synthesis of what you find, and will also point someone in the direction of good potential resources.

These questions can be framed in a variety of ways. For instance, the PICO does not always occur in this strict order. The questions need to be framed in a way that makes sense for the type of Evidence Based query that someone needs to make.

PICO questions can be broken down into five categories of what they are able to address: Therapy, Etiology, Diagnostic, Prevention, and Meaning.

Therapy questions

Therapy questions seek to find answers about how specific treatment—be they pharmaceutical, environmental, rehabilitative, or behavioural—change the impact of a particular condition or aspect of a condition. It can be simply framed as “what is the effect an Intervention has on an Outcome compared with a Comparison in Patient or Population?”

Example

In Patients with Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) what is the efficacy of direct oral anticoagulants compared to parenteral anticoagulants followed by VKA for reducing recurrence? (Nursing).

P = Patients with VTE

I = oral anticoagulants

C = parental anticoagulants

O = reducing recurrence.

Activity: Now you try

Etiology questions

Etiology questions seek to find the causes or factors that cause certain conditions or symptoms. It can be phrased as “Is a Population or Patient who have Intervention at increased or decreased risk of Outcome with or without a Comparison?” In this case the intervention is a factor that might contribute to the development of a condition, injury, or symptom.

Examples

- Are students with fine, clean hair at increased risk of exposure to head lice compared to those with curlier, dirtier hair in an elementary school environment? (Nursing)

- If sexually active high school students determined to be at high risk are given a simulated infant doll scenario compared with materials on the proper use of birth control methods will there be fewer pregnancies during the school year among the group? (Social Work)

- Are men from military families at an increased risk for alcoholism after combat duty compared with men from civilian families in the military? (Occupational Therapy)

- Are adults from low-income households more likely to develop heart disease than adults from higher-income households? (Public Health – Epidemiology)

Diagnostic questions

Diagnostic questions seek the answers to how to best diagnose conditions. In these questions the Intervention is the diagnostic tool, which could be a technological tool like certain types of imaging, a questionnaire, a test, a measurement tool, or a series of tests compared to others. Many of these questions are best phrased as “Are/Is an Intervention more accurate for diagnosing/testing for a Patient/Population compared to Comparison for an Outcome?”

Examples

- Does regular testing for a combination of Body Mass Index compared to Blood Glucose accurately predict risk for type 2 diabetes? (Nursing)

- Is the Phalen test more accurate for diagnosing Carpal Tunnel Syndrome compared to electrodiagnosis in patients complaining of hand swelling? (Physical Therapy/Occupational Therapy)

Prevention questions

Prevention oriented questions seek answers to how to prevent certain conditions from occurring. In these questions, the Intervention is the preventative measure, which could be environmental, lifestyle, dietary, chemical, screening, or other factor compared to either no intervention or standard practice. A prevention question is best phrased as “Does Intervention best prevent an Outcome in a Population compared with Comparison?”

Examples

- Does turning a non-ambulatory patient prevent the prevalence of pressure ulcers compared to the use of pressure mattresses? (Nursing)

- Does strength and balance training more effectively prevent falls in elderly individuals compared to those who attend fall prevention programs? (Physical therapy/Occupational Therapy)

- Do Summer jobs influence lower rates of crime among youth from lower socioeconomic backgrounds compared to those who are enrolled in summer school? (social work)

- Does an epidemiological approach influence the rate of gun violence in affected communities compared to the influence of law enforcement? (Public Health)

Meaning questions

Meaning questions seek answers that show how a group of people experience a disease, treatment, therapy, diagnostic test, or other intervention. In this question, framework the P is the population of people experiencing a certain Intervention or even illness. The Comparison in questions like these can be unsaid or be a valid comparison group, such as comparing one intervention group’s experience to another. And the outcome is that which the group perceives. A question like this can be phrased as “How does a Population with a particular intervention perceive of a certain outcome compared with another intervention?”

Examples

- How do nurses in Ambulatory Units experiencing burnout experience Interprofessional education? (Nursing)

- How do sexual assault survivors recovering from orthopedic surgeries experience physical therapy clinics? (Physical Therapy)

- How do people who have previously but no longer received SNAP benefits living in private housing perceive their own food security? (Public Health)

- How do unmarried white women in trailer parks perceive domestic violence laws? (Social Work).

References

Bronson, D. E., and Davis, T. S. (2012). Finding and evaluating evidence: Systematic reviews and evidence-based practice. Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195337365.001.0001

Heltzer, K. (n.d.) Finding research evidence, student activity 2. https://www.d.umn.edu/~kheltzer/sw5095sp08/handouts/develop_research_to_practice_q.pdf

Levine M, Ioannidis J, Haines T, Guyatt G. (2008). Harm (observational studies). In G. Guyatt, D. Rennie, M. O. Meade, & D. J. Cook (Eds.). Users’ guides to the medical literature: A manual for evidence-based clinical practice. (2nd ed., pp. 363-381). McGraw-Hill.

Mayes, T. L., Bernstein, I. H., Haley, C. L., Kennard, B. D. & Graham J. Emslie, G. J. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised in adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 20(6): 513–516. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2010.0063

Melnyk, B. M. & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2011). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Pfeiffer, P. N., Heisler, M., Piette, J. D., Rogers, M. A. M., & Valenstein, M. (2011). Efficacy of peer support interventions for depression: a meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 33(1), 29-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.10.002

Richardson, W.S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J. & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP Journal Club, 123(3), A12-A13.

Russell, S. T., Ryan, C., Toomey, R. B., Diaz, R. M., & Sanchez, J. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent school victimization: implications for young adult health and adjustment. Journal of School Health, 81(5), 223-230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00583.x

This chapter is adapted from:

“Question Frameworks” in “Evidence Based Practice” by Carrie Wade, licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Applying Research in Practice by Duy Nguyen, licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.