Chapter 11: Ethical And Social Issues in CBA

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, students should be able to:

-

Recognise the interaction between ethical concepts and social issues in economics.

-

Identify and apply the three ethical theories: utilitarianism, deontological, and virtue ethics.

-

Consider consequences of ethical decision-making in cost-benefit analysis.

-

Reflect on ethical decision-making.

When Policy and Philosophy Collide

“Logic clearly dictates that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” – Spock, The Wrath of Khan (1982)

Up until this point we have treated every policy, program, or project as a black and white decision related to the calculated net present value – reject a project when the NPV is negative and accept the project when the NPV is positive. In reality, decision-makers would be fools to deal in absolutes.[1]

The foundations for cost-benefit analysis are underpinned by welfare economics. Welfare economics focusses on maximising the total social surplus. i.e., maximising the total benefit to society as a whole. When conducing a cost-benefit analysis, the process involves identify the costs (negative impacts) and the benefits (positive impacts) to determine if policy, program, or project will provide gains to society. As mentioned before, this process of selecting the largest gain is done by selecting the project with the highest net present value (NPV) as it measures our net social benefit – assuming that all costs and benefits to society have been accounted for. By selecting the project with the largest NPV, we achieve allocative efficiency which is vital in the decision-making process when approaching economics from a traditional perspective.

However, measuring efficiency is challenging as highlighted in Chapter 8. When conducting a CBA, an analyst only evaluates the results from a set of possible outcomes providing a point of comparison. This comparison allows for the identification of the best allocation of resources from the set of possible choices. When conducting an analysis from only a series of known possible options, we cannot identify all possible uses of the resources. Furthermore, while CBA provides a structured framework in which we can identify the best projects in a systematic way and has become an accepted tool for the evaluation of decisions, it does not provide context on the implications on fairness or equity in the decision-making process. Consequently, this chapter will cover the interaction between contemporary ethical and social issues and the role of cost-benefit analysis as a tool to support decision-making.

Why Consider Social Issues in Decision-making?

Economic issues revolve around what goods and services to produce, how to produce, how to distribute goods and services, and whom you are producing for (the consumption of goods and services). This comes back to the idea of scarcity and how economic agents try to satisfy unlimited wants and needs with limited resources. Often secondary to economic issues is the application of economic principles to social issues.

Social issues are distinct from economic issues. Social issues are matters that directly or indirectly affect a person, groups of people or society. Social issues are considered problems related to moral values. Social issues focus on problems or concerns that undermine the wellbeing of society, usually with an emphasis on negative influences. Consequently, social issues can be subjective or objective.

Key Concept – Morals

Morals or Moral values are standards of behaviour or principles of what is right or wrong.

Common examples of social issues in economics revolve around how public policy can be used to address environmental issues, distribution of wealth and income, poverty and inequality, gender differences, altruism, crime and corruption, gambling, homelessness, etc. These issues are complex in nature and cover many areas of economic studies. Contemporary social issues in economics are often related to “wicked problems” or “grand challenges” in economics – issues that do not have an easy solution.

The focus of social issues in cost-benefit analysis revolves around utilising social cost-benefit analysis to evaluate the choices made by firms and governments. Hence, the emphasis on social evaluation and the integration of social impacts into a CBA – beyond economic and financial appraisal methods previously dominating the literature.

Implicitly we have approached cost-benefit analysis from a social perspective from the introduction in this book to emphasise the use of CBA to evaluate and address social issues and social choices. The question then becomes – why do we care about ethics in decision-making?

Why Consider Ethics in Decision-Making?

Ethics is not often considered part of “doing” economics as it falls outside of the analytical style of developing and implementing models to communicate concepts and theories. Many areas of economics that undergraduate students have engaged with are likely to ignore or dismissed ethical overtones in their applications. However, all economic activities, policies, and decision-making processes have some form of ethical consequence in the form of value judgements. A value judgement is an assessment of an action or choice as good or bad in terms of one’s standards, objectives, or priorities. Consequently, economic policy implemented by governments can be influenced by value judgements. Therefore, we cannot exclude the role of ethics in learning economics if we want to achieve social development.

Additionally, there is a clear role of ethics in economics and policy analysis. As highlighted by Hausman and McPherson (2016), an understanding of moral philosophy and ethical theory helps individuals “do” economics.

Key Concept – Ethics and Social Development

Ethics refers a defining set of principles that identify what is morally good and bad – what is right and what is wrong.

Social development – actions that are taken to improve the social, economic, cultural, and environmental conditions of society.

Why Consider Ethics and Social Aspects in Cost-Benefit Analysis?

Society reflects the ethics and morals of the time. Rethinking of the ethical foundations of modern economics allows a shift in focus from “homo economicus” towards critical social issues including (but not limited to) climate change, financial crises, health crises, resource depletion, poverty, and food insecurity. The objective of discussing ethics is not to determine what is “right” and “wrong” but to sensitize and illuminate ethical questions. The goal of economic efficiency can often ignore fundamental ethical norms, including moral or immoral actions (such as climate change inaction or deliberately harming other people). By highlighting the interaction between economics and ethics, we improve the ability to make complex decisions, think critically and embark on our own personal development.

From a cost-benefit analysis perspective, consideration of ethical perspectives ensures that distributional impacts are appropriately identified and evaluated. Therefore, integrating ethics into the evaluation of cost-benefit analysis is necessary – even if only as reflective activity. This is challenging as there is significant diversity in ethics and morals. Specifically in CBA, it is important for us to consider all relevant stakeholders who may be impacted by a policy, program, or project. It is crucial that the implications of implementing a policy or program extends beyond monetary evaluation and considers different social, ethical, philosophical, and cultural backgrounds.

The Difference Between Ethics and Morals

Generally, the words ethics and morals are used synonymously implying there no difference between the concepts. However, for the purpose of this chapter, it important to understand the nuanced differences between ethics and morals. Making a simple distinction between the two concepts allows a better understanding of the interconnected nature of ethics and economics in both the cost-benefit analysis framework and decision-making in general.

Key Concept – Ethics Versus Morals

Morals or Moral values are standards of behaviour or principles of what is right or wrong. Morals are dictated or framed by society or culture. There is an emphasis on shared social norms.

Ethics are rules of conduct or conventions that govern an individual’s behaviour in deciding what is good or bad based on the moral beliefs or values in society. Ethics are chosen by a person or can be a standard identified by a community (such as Ethical Standards Boards). Ethics can therefore be considered a critical reflection on morals.

Unethical behaviour is behaviour that does not reflect the underlying the moral beliefs or values in society.

To highlight the difference, we can think of ethics in the purpose of economics as a “What should I do?” question, and morals are “How it should work”. Morals have both cultural and social aspects. Social norms, conventions, and cultural values will impact our morals. Whereas ethics are individual activities or beliefs in relation to the morals that we observe. Ethics is therefore an individual assessment of what is good or bad, while morality is a subjective community-based assessment of what is considered right or just in society. Consequently, we can think of ethics as a critical refection on moral values.[2]

Morals are hard to define as there is a prominent level of culturally and socially acquired variation. What is “right” or “wrong” in one country may be perfectly acceptable in another country. For example, many countries around the world have implemented “Right to Die” or “Assisted Dying” policies allowing for voluntary euthanasia for individuals with terminal illness. However, in some countries it is considered morally wrong to implement such programs. Additionally, our personal ethics may not reflect the predominant moral view of society. Some people may be for or against voluntary euthanasia on a personal level.

When attempting to make moral decisions, we may have to sacrifice our own personal interests or personal ethics. Therefore, moral decision-making moves ethical decision-making into the social sphere. As can be seen, the two concepts are related, but the moral decision-making is more of encompassing of society as a whole, whereas ethical decision-making is individual level choices. An ethical action is one that is considered morally acceptable. Any ethical action must be considered morally acceptable for it to be ethical by definition.

Obviously, ethics and morals are very important in the context of decision-making in economics due to value judgements in our analysis and recommendations to policymakers.[3]

Case Study – Woolworths leaves pokies behind.

In 2019, Woolworths Group announced a “de-merger” from the Endeavour group. Through this process Woolworths Group plans to separate pokies, gambling, and liquor related revenue worth $700 million per year from the corporation. Commentary on the issue highlights problematic gambling and reputational risks associated with this type of investment to Woolworths Group shareholders and a lack of cohesion with “Family Friendly Values.” By separating Woolworths Group from the liquor and gambling markets, Woolworths is signalling that these investments are unethical and unaligned with the company’s ethical values – forgoing the earnings in favour of following their internal beliefs on what Woolworths Group should represent.

For additional information regarding the benefits and costs of this decision by Woolworths Group, consider reading this Conversation Article:

What is an Ethical Dilemma?

An ethical dilemma exists when there is not a simple choice between what is right and wrong. When facing an ethical dilemma, it often leads to unpleasant choices. To solve ethical dilemmas, we need to apply complex judgements.[4] By understanding the role ethics takes in decision-making, we can identify and analyse conflicts associated with ethical dilemmas.

Key Concept – Ethics and Economics

Reflection on economics and morality can potentially help many economists make better decisions, develop effective public policy, and assist in solving ethical or moral dilemmas.

COVID-19 Lockdowns as an Ethical Dilemma

One of the ethical dilemmas at the forefront of contemporary discussion is lockdowns. Debate rages publicly on the trade-off between the economy and human life. By imposing lockdowns, infections can be managed and the spread of COVID-19 through the population can be controlled without significant hospitalisations and ICU intakes. This is important to ensure the healthcare system is not overwhelmed.

However, on the other side of the discussion is economic productivity. Lockdowns are known to negatively impact on short term economic growth, reduced social mobility, and the increased cost to mental health across the board (Norheim et.al., 2021). Additionally, increase inequity for socioeconomically disadvantaged or marginalised groups has push millions more people into extreme poverty (World Bank, 2021). This has exacerbated wealth inequality and inequality of opportunity – issues that have been at the forefront of discussion in economics for the past decade.

Consequently, lockdown policies can impact many social and economic factors. These factors need to be evaluated by decision-makers leading to many questions relating to ethical and political trade-offs. If you are interested in reading more about these issues, there are many resources online (peer reviewed and from alternative sources). Consider reading this editorial by Whitehead, Taylor-Robinson and Barr (2022) and this opinion piece by Gak (2020) as a starting point.

Efficiency, Ethics, and the CBA Framework

As mentioned in Chapter 1 and again in Chapter 6, there is a clear link between cost-benefit analysis and welfare economics. Cost-benefit analysis is a tool for evaluating project, programs, and policies to ensure the selected use of limited resources is efficiently allocated. Our tool for evaluating the optimal allocation of resources it the net social benefit (![]() ), which is often measured by calculating the net present value when a project has an extended life. Assuming all social benefits and social costs are accounted for in the calculation of the net present value, analysts can identify the project that maximises the net social benefit. By accepting the projects that meet the decision rules outlined in Chapter 2, scarce resources are allocated to their most valuable use. Therefore, cost-benefit analysis allows for the identification of efficiency. By operating as efficiently as possible, we should achieve pareto optimality.

), which is often measured by calculating the net present value when a project has an extended life. Assuming all social benefits and social costs are accounted for in the calculation of the net present value, analysts can identify the project that maximises the net social benefit. By accepting the projects that meet the decision rules outlined in Chapter 2, scarce resources are allocated to their most valuable use. Therefore, cost-benefit analysis allows for the identification of efficiency. By operating as efficiently as possible, we should achieve pareto optimality.

Efficiency is a normative criterion for decision-making which can be derived from utilitarianism. Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that seeks “the greatest good for the greatest number”. In economics, this is equivalent to ensuring the maximisation of total social surplus. In cost-benefit analysis this is akin to selecting a project with the largest net social benefit. At its essence, utilitarianism involves maximising total utility of society without the consideration of the distribution of benefits and costs. A CBA analyst will undertake any policy or project that has a net benefit greater than zero as the benefits will exceed the costs. Therefore, cost-benefit analysis can be considered operationalised utilitarianism.

Social Critiques and the Kaldor Hick’s Criterion.

Social critiques of cost-benefit analysis focus on the utilitarian assumptions. If the total social surplus is maximised, it is possible to trade utility gains and utility losses in a way that allows everyone to be made better off without anyone being made worse off. This is the key assumption of utilitarianism. Any cost-benefit analysis that identifies a policy or project as unequivocally beneficial (through a positive net social benefit) provides the government an opportunity to take actions or implement policies to ensure those winners who receive positive payoffs can compensate losers who have negative payoffs the implementation of the policy or project. The compensation process would therefore meet the Kaldor-Hicks’s criterion, which is a central feature of the utilitarian assumption.

However, for practical purposes we know governments seldom implement compensation in the real world. Hence, decision-makers are facing an equity – efficiency debate. To resolve these debates, understanding different ethical frameworks allow us to evaluate the relevant objectives of a policy or project to ensure effective decision-making.

Key Concept – Normative versus Positive Economics

Normative economics involves analysing outcomes of economic behaviour to evaluate outcomes as good or bad. Normative economics is subjective in nature – “what ought to be”. Positive economics is about understanding behaviours without making judgements about the outcomes. Positive economics is objective in nature – based on data and facts to describe “what is”.

Ethical Theories

Understanding ethical theories and their applications to economic and social issues provides guidance to evaluate moral dilemmas. An ethical point of view allows for better evaluation of decision-making through managing the context of decisions, resolving conflict, and dealing with uncertainty. Furthermore, by understanding some basic ethical theories, we can develop an awareness of the influence that values and behaviours may have on others.

For the purpose of evaluating decisions within a cost-benefit analysis framework, we will consider three ethical theories.

-

- Utilitarian ethics

- Deontological ethics

- Virtue ethics

Note there are many ethical theories that can be applied into the context of decision-making. By studying whether actions are ethical we are applying normative ethics for practical purposes.[5]

Utilitarian Ethics (Utilitarianism)

As mentioned previously, utilitarianism is the ethical theory that aligns with economic efficiency. Utilitarian ethics focuses on making decisions by identifying “the greatest good for the greatest number”, which directly aligns with the maximisation of total social surplus in the context of cost-benefit analysis. To better understand the link between utilitarianism and economics, we need to understand that utilitarianism is a form of consequentialism – the evaluation of a decision focuses on the consequences of the action or decision. To apply utilitarianism, a decision-maker determines whether the consequence or outcome of the decision is considered morally right or wrong on the basis of whether the action increases utility for society as a whole. In the case of CBA this is simply recognised by a positive net present value.

Strengths of Utilitarianism as an Ethical Theory for Decision-making

1) It provides a simple basis for formulating and testing policies – by focusing on whether the outcome or consequence is considered right or wrong there are fewer issues for evaluating a decision. In a CBA framework it is very easy to identify the consequences of the policies or projects we are evaluating.

2) Objective way of resolving self-conflict – overall happiness or social utility is maximised under utilitarianism. This is an objective fact. Self-conflict is resolved by focus on society rather than the individual. This aspect also means there is no set of prior beliefs involved in the evaluation of the decision and the result is considered democratic.

3) It is result orientated – as utilitarianism is a form of consequentialism. An action or decision is consider right or wrong based only on the consequences without consideration of the character or motivation. Consequently, utilitarian ethics often dominates in applications and discussions of ethical decision-making.

Criticisms of Utilitarianism

1) The consequences of actions often go beyond the time frame for which the decision is made – For example, we may consider a project that taxes alcoholic beverages. If we choose a time frame of 20 years to evaluate our tax policy, we may not capture the consequences outside of this time frame appropriately. Long term consequences are sometimes lacking in the analysis and decision processes.

2) Utility measures are hard to effectively determine – For instance, loss aversion, the endowment effect, reference dependence, framing, the desire for cognitive ease, status-quo bias, etc. may affect the outcome of a decision outside of the utilitarian framework. We would need to ensure the estimated gains and losses associated with a program are accounted for in a way that captures the asymmetry of the impacts.

3) Often ignores minorities – Under utilitarianism, the decision is driven on what is best for society. Distributional impacts of decisions are not accounted for. When implementing policies, we should consider any groups that may be disproportionally affected or subjected to unintended consequences. Essentially, in practice we would need to consider how to protect minorities and at-risk groups. Harming minority or at-risk groups is not good for the establishment of a positive reputation. Furthermore, the consequences of harms may be substantial. If these impacts are not accounted for the implications of the decision could be significantly damaging and result in irreversible effects. There is a fairly easy fix for this in a CBA framework, by looking at the distributional analysis outlined in Chapter 9 to identify these issues.

4) We often ask the question “should morality be tied to happiness?” – While is it important to understand that people are always in pursuit of happiness and happiness is a worthwhile goal, there is heterogeneity in individual preferences along with heterogeneity regarding where each person derives their utility from.

Case Study: Fight Club – The Recall Coordinator’s Formula

This is a scene from the movie Fight Club (1999). You can watch a clip of this scene at the following external link to Youtube for better context of the excerpt below.

“A new car built by my company leaves somewhere traveling at 60 mph. The rear differential locks up. The car crashes and burns with everyone trapped inside. Now, should we initiate a recall? Take the number of vehicles in the field, A, multiply by the probable rate of failure, B, multiply by the average out-of-court settlement, C. A times B times C equals X. If X is less than the cost of a recall, we don’t do one.”

There is a clear ethical dilemma in this example. By applying the Recall Coordinator’s Formula, the assessor is applying utilitarian ethics. It leaves a clear question at the end – is this the appropriate action to take?

Deontological Ethics

Deontology means the “study of duty” (Larry & Moore, 2021). Consequently, deontological ethics focuses on whether the action itself is considered right or wrong based on a series or rules or duties. The consequences of the actions are irrelevant to the decision, as the consequences are often difficult to foresee. The use of deontological ethics in decision-making relates to developing a sense of goodwill by following the universal moral norms or moral laws. In some instances, duties can be reflected in what the law states is right or wrong.

Deontologists often argue that we are unable to truly know the result of our actions and therefore we cannot determine whether it is right or wrong based on the consequence. Under deontological ethics, evaluation of the decision is based on the action in following moral duties or rules. Hence, we can think of deontological ethics as the opposite of utilitarian ethics.

The rules or duties that are applied to deontological ethics are often driven by universal moral laws. However, in some cases duties may also be tied to professional values or standards. These duties can be framed in a positive or negative format. Examples of duties include:

– Do not harm others

– Do not steal

– Do not cheat on examinations

– Follow the law

– You should keep a promise

– Respect your elders

– Avoid anti-social behaviours

– Protect people’s fundamental human rights

Deontological ethics does not require the evaluation of the costs and benefits of the action. Therefore, it is an alternative method for evaluating decision-making that does not fall into the cost-benefit analysis framework we have considered thus far.

Strengths of Deontological Ethics as an Ethical Theory for Decision-making

1) Perpetuates the importance on every individual – The approach is considered universal with a focus on fairness, consistency, and moral treatment of all people as equals. Consequently, it provides a basis for human rights. For example, one of the duties is to “not harm others”. Even when the consequences or result of harming someone is considered good, deontological ethics highlights that the action of hurting others is fundamentally wrong.

2) There are natural moral laws or duties – These natural moral duties are a clear set of rules for the decision-making process on whether the action is considered right or wrong. These duties are based on reason and are universally relevant regardless of race, religion, nationality, or gender.

3) Duties are based on reason and not on subjectivity – Unlike utilitarianism, costs and benefits for society are not evaluated and therefore there is no subjective assessment of what is right or wrong under deontological ethics if the rules or duties are followed.

Criticism of Deontological Ethics

1) Moral conflict may exist – Under deontology, there is no clear way to resolve conflicting duties or moral conflicts. For example, when there is a duty to keep a promise conflicting with the duty to tell the truth or breaking a promise to ensure no harm is done to another individual. To demonstrate this further, suppose you were to attend a friend’s wedding and on the way to the venue you saw a pedestrian get hit by a car. If you stop to help the pedestrian in trouble you will break the promise to your friend but the action of helping someone in distress is considered itself “good”. Conflicts in duties often arise when circumstances change.

2) Moral laws differ across society – The existence of cultural relativism rejects the possibility that there are uniform standards or duties across cultures. Cultural relativism is the idea that cultures are fundamentally different from each other and therefore the moral frameworks and duties will be different between countries and societies.

3) Deontological ethics only works if all people agree on the same duties – Emphasising the role of the individual in determining if an action is moral or not.

4) Duties change over time – An extension of the previous limitation on social differences. Social norms and morals adapt from generation to generation resulting in the duties changing over time. For example, we can consider views and duties relating to climate change in the 1980-90’s are still valid or should our duties reflect the new views of climate change now in the 2020’s?

5) There is a possibility of making the “right choice” that has bad consequences – Again if the consequences are severe and may hurt or have unintended consequences on minorities or at-risk groups of society, we should consider whether evaluating the decision based only on the action appropriate. Therefore, it is possible to implement decisions that make society worse off under deontological decision-making.

6) Underestimates the role of utility in decision-making – The happiness of individuals and/or society is not considered.

From the description of deontological ethics, it is easy to see that the process is focused more on individual level decision-making based on what actions are considered appropriate, and utilitarianism is focused on social perspective of decision-making to maximise social benefits.

Key Concept – Should You Keep a Promise?

Asking the question about keeping a promise allows for the evaluation of choices under Deontological Ethics compared to Utilitarianism. Deontologist would often argue that you should keep a promise made regardless of the consequences. However, utilitarians will argue that we should only keep promises if the result of keeping the promise is better than the consequences under the alternative situation. This is a clear actions versus consequences scenario.

Virtue Ethics

Virtue ethics is developed on the idea that we become good by practising good virtues rather than following external rules. Actions that enhance good aspects of human interactions or decisions are considered good. Virtues are characteristics, motivations, attitudes or dispositions that are considered “good”. Specifically, a virtue can be thought of as a habit or character trait that shows ideals and is considered part of an individual’s identity, affecting their choices (Jonsson, 2011). Examples of virtues, generosity, honesty, compassion, self-control, etc. Unlike deontological ethics that focuses on moral duties, virtue ethics focuses on the internal motivation of the decision-maker. When applying virtue ethics to economics we are asking what makes a good person rather than what makes a good action or provides a good result in the decision-making process.

Strengths of Virtue Ethics as an Ethical Theory for Decision-making

1) Virtue ethics is not bound by rules – There is an element on flexibility as the focus is on being virtuous individual. When attempting to make decisions based on virtuous characteristics, there is better recognition of rational behaviour and social norms.

2) Involves a personal aspect to the decision-making process – Often framed as a “Should I do this?”, philosophical question. People over their lifetime develop and refine their virtues. Therefore, virtues in decision-making are linked to one’s ethical principles which can develop and refine over time.

3) There is an emphasis on moral development – Through moral development and moral education there can be changes and improvements to habits of people to improve and advance society. For example, changes to consumer choices related to the use of single use plastics and plastic waste started at an individual level with changes to personal behaviours (through recycling, reusable cups, reusable straws, etc.). These changes in morals have consequently led to many governments implementing bans on single use plastics.

Criticism of Virtue Ethics:

1) Does not provide a direction for the problem or decision being evaluated – There is no clear guidance for moral dilemmas. Virtue ethics strictly looks at internal motivations of the person making the decision rather than the obligations to society.

2) There is no general agreement regarding what good virtues are – Like deontological ethics where duties and rules can be hard to define, it is also difficult to define what good virtues are. There is heterogeneity driven by cultural and social norms.

3) There are often conflicts of virtues – For example, suppose you were to attend a friend’s wedding and on the way to the venue you saw a pedestrian get hit by a car. The virtue of charity requires that you help someone in need (the pedestrian in distress), but at the same time the virtue of loyalty requires that you keep your promise to your friend. In either case, the decision-maker acts wrongly due to conflicting virtues.

4) Can be often considered “situational ethics” – Situational ethics is when the ethical decision-making is context dependent. Virtuous characteristics should be unchanged over time. However due to the potential for conflicting virtues like those mentioned in point 3 above, the result of the decision would change depending on the context.[6]

Key Concept – Visiting a Friend Who is Sick

Suppose you have a friend who has been sick for a few days with a non-contagious illness. If you visit your friend because it is your duty (deontological) or due to the expected consequences (utilitarian), it may be considered a moral flaw in your friendship as the visit is not conducted based on the “right” intentions. However, from the viewpoint of virtue ethics, being a good friend is considered virtuous characteristic. Therefore, by visiting your friend you are being morally good.

The Three Ethical Theories in Economics and CBA

These three theories form the basis of normative ethics conversations. It is important to consider ethical and social aspects of decision-making to ensure all relevant stakeholders are accounted for and evaluated as part of the CBA. There is diversity in ethics and morals resulting in situation where the choices of government decision-makers may not reflect the norms of society. As CBA analysts, it is important to consider the ethical implications of policies, programs, and projects to ensure the final recommendations of the analysis are appropriate. The application of these three ethical theories also helps decision-making through managing context, conflict, and uncertainty that may arise.

Case Study: Deontological Concerns Arise in Health Economics

Health economics is a specialised area of economics with its own challenge. One challenge that health economists are often affronted with is the ethics of using CBA to value human life.

To effectively conduct a cost-benefit analysis all costs and benefits must be expressed in a common measure, typically dollars, including things not normally bought and sold on markets. This includes improvements in quality of life, increased mortality (in years) and other health benefits – all of which require monetisation. To ensure that the social CBA reflects the true NPV these aspects should be captured a CBA analyst would ask “How do you value someone’s life?”.

When thinking of the ethics of valuing a life, a further question would be “Should you value someone’s life?”. Consequently, the area of health economics is growing and adapting to create measures that do not create a moral dilemma such as Cost effectiveness analysis (CEA), and Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs).

Examples of Ethical Applications – What is the Right Thing To Do?

Ethical understanding helps refine and manage decision-making, resolve conflict, and develop awareness of values and behaviours that influence our choices. To further refine our understanding of ethics, this section provides examples of ethical dilemmas and how various ethical theories can be used to explain the decisions made outside of the utilitarian approach in cost-benefit analysis.

Example 11.1

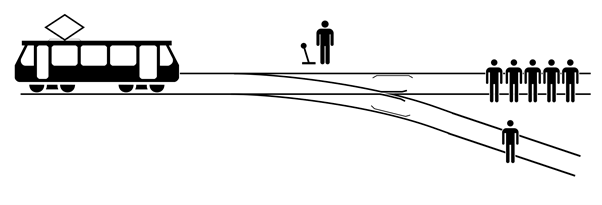

The Trolley Problem

The trolley problem was first proposed by Philippa Foot in her paper The problem of abortion and the doctrine of the double effect (1967).

The scenario:

“The driver of a trolley has passed out at the wheel, and their trolley is hurtling out of control down the track. Straight ahead on the track are five people who will be killed if the trolley reaches them. You are a passer-by, who happens to be standing by the track next to a switch. If you throw the switch, you will turn the trolley onto a spur of track on the right, thereby saving the five. But someone is on that spur of track on the right; and he/she will be killed if you turn the trolley.”

What do you do?

In the context of the trolley problem, we are faced with the dilemma whether to throw (or flip) the switch. The choice made in this scenario will depend on the ethical approach of the individual making the decision.

Utilitarian Approach.

In this classic example, when applying utilitarianism you should flip the switch, because you save five people, and you lose one person. Thereby you are maximising the number of lives saved (or minimising the number of lived lost). From a CBA perspective this is the correct course of action as the benefits of flipping the switch outweigh the cost i.e., benefit = 5 people live, cost = 1 person dies, therefore the net benefit is 4 lives.

Deontological Approach.

To apply deontological ethics to this scenario, the action must be evaluated. The consequences of the action can be ignored. The action is “flipping the switch”. When considering if flipping the switch is immoral, a deontologist would consider if the action of killing someone is moral as pulling the switch is effectively killing someone. Therefore, a deontologist would do nothing in this scenario and the five people would die.

Virtue Ethics Approach

By focusing on the moral approach to the conundrum, the result of the trolley problem is much more complex. Someone applying virtue ethics does not have any interest in whether you save five lives or one. Remember the point of following a virtue ethics approach is about the development of a virtuous character. Therefore, the evaluation from the standpoint of a virtue ethicist is about identifying who you are as a person in responding to the situation. The question would really be whether your action or decision reflected virtuous characteristics like compassion, valuing life, acting in fairness, etc. Virtuous characteristics are diverse, and the ranking of these character traits is heterogenous leading to possible several solutions.

For example, someone who values saving the most lives will flip the switch and steer the trolley away as it is simply the kind of thing a virtuous person would do. However, some would highlight the damage done to your character by taking this course of action. In comparison, suppose the single person on the track who would die if you threw the switch is your girlfriend or boyfriend. You have the opportunity of saving them at the cost of the five other people on the second track. In this case you may not flip the switch as you value love as an important virtue.

Although it is best to note that this is not an exhaustive set of solutions under virtue ethics as it will depend on the characteristics underlying what an individual considers as virtuous.

Conclusion

No clear decision exists under all three theories.

The trolley problem outlined in Example 11.1 is often an introductory example used when learning ethics. The trolley problem is a question of human morality and a key example of where actions, intentions, and consequences can be considered. There is no single correct answer, and there are many ways of thinking through the dilemma.

One key issue the trolley problem often does not consider the hypothetical bias caused by a hypothetical problem. When faced with an actual variation of the trolley problem, our approach can change depending on the circumstances. The result is forced decision-making. A second limitation involves the problem morphing into a situational ethics approach where the ethical decision-making is contextual or dependent on a set of circumstances.

The Trolley Problem (Season 2, Episode 5) of The Good Place illustrates the challenges of the trolley problem. You can view the scene at this external Youtube link. The xkcd comic in Figure 11.3 highlights the situationism of the trolley problem.

If you are interested in reading more about the trolley problem, consider reading this Conversation article: The trolley dilemma: would you kill one person to save five?.

Example 11.2

The Trolley Problem Reframed.

The scenario adapted from Andrade, (2019).

“A transplant surgeon has five patients, each in need of a different organ, who will each die without that organ. Unfortunately, there are no organs available to perform any of these five transplant operations. A healthy young traveller, just passing through the city the doctor works in, comes in for a check-up. During the check-up, the doctor discovers that his organs are compatible with all five of the dying patients. Suppose further that if the young traveller were to disappear, no one would suspect the doctor.”

What do you do?

This example is a more extreme version of the trolley problem that is often discussed in health economics and medical fields which has the same premise of saving five people at the cost of losing one person. However, this scenario can also be considered as a dilemma of killing one person or killing five people.

Utilitarian Approach.

Under the utilitarian approach the result would be the same as the initial trolley problem in Example 11.1 – the doctor should sacrifice one person to save five thereby minimising the number of deaths.

Deontological Approach.

Under deontological ethics, the scenario is more complex. The doctor has several duties but there are two we can use to highlight the point; (1) the doctor has the duty to help the five-transplant patient, and (2) the doctor has a duty to “do no harm”. This can be seen as a conflict in duties. Consequently, we would need to consider the trade-off between positive and negative duties. A positive duty is a duty to take an action. A negative duty is a duty to NOT take an action. In this situation the positive duty would be to save the five transplant patients whereas the negative duty would be to do no harm to others. In most instances the negative duty would be prioritised over the positive duty – and in this case the inaction of the doctor to save the lives of the transplant patients would not be deemed unethical.

Virtue Ethics Approach.

Comparable with the initial trolley problem, the solution for virtue ethics is not clear cut and therefore we cannot designate a morally correct action. The result of the decision would reflect the virtues by the individual decision-maker.

Conclusions and Comparison to the Initial Trolley Problem

When the general public is provided with this scenario, the consensus for ethical theories and the general public is that it would not be ethical to kill the traveller (Andrade, 2019). Additionally, the wider philosophical community always conclude that it is unethical to sacrifice the traveller in this instance. Therefore, the result of this reframed trolley problem leads to an overall realisation that the opposite conclusion the opposite conclusion happens often in the initial trolley problem. In the initial trolley problem, the answer, the majority of people come to is that “you are going to flip the switch”.

This second reframed trolley problem with the transplant patients is a bit more extreme as an example to highlight the difficulties of ethical decision-making. This example emphasises the ethical grey areas of dilemmas and highlights why ethical standards exist for many professions. So ethical dilemmas are quite interesting in that sense. And there’s quite a few different ethical dilemmas we can consider in economics.

Example 11.3

Academic Dishonesty

Academic integrity is linked to moral integrity in how individuals determine what is right and wrong. Consider the situation where you hire someone to complete your assessment for you (known as contract cheating). Cost-benefit analysis provides a framework that highlights why a student might engage in academic dishonesty. In this instance, the benefit would be a passing grade and the cost would be the price paid to the contractor.

Utilitarian Approach.

When taking a utilitarian approach to the decision, a student will cheat if the net benefit is greater than zero.[7] However, this decision conflicts with ethical and moral decision-making under deontology and virtue ethics approaches.

Deontological Approach.

Under deontological ethics, academic integrity is a duty to uphold, and the action of cheating is considered wrong. This results in the conclusion that is not socially acceptable to cheat.

Virtue Ethics Approach.

Under virtue ethics, choosing to act with integrity, honesty and academic excellence are all virtues that would discourage contract cheating.

Conclusion.

Consequently, the impacts of ethical decision-making can be seen in the decision-making of university students around the globe.

Why does Ethics Matter to Economics in General?

Policy analysts are required to weigh up the relative merits of alternative policy responses to any given problem. To do this in a systematic fashion, policymakers must establish a criteria for judging each alternative to assess the relative expected performance of each possibility. In cost-benefit analysis this is done by calculating the net social benefit using the net present value decision rule. However, a CBA analyst is not often the decision-maker or policymaker who provides the final judgement on whether a policy, project, or program goes ahead. Policymakers often use three key criteria when evaluating their options

1) Efficiency

2) Equity

3) Administrative simplicity

Taken together these three criteria lead to quality, ethical and timely decision-making.

Additionally, ethics is important to economics as each decision we face may involve an ethical or moral dilemma. For example, the economics of climate change is inseparable from social ethics as decision-makers need to find a balance between economic growth, the welfare of society (present and future) and the environment. Consequently, social understanding and ethics are core to well-rounded choices.

Ethical Dilemmas at the Forefront of Economics Outside of CBA

There are many instances of ethical dilemmas in economics. Some examples for consideration are highlighted below:

- The economics of climate change – it is hard to disentangle the impact of climate change and the requirements or obligations related to climate interventions (now and in the future).

- The effects of globalisation on poor countries – taking advantage of workers in poorer counties including the use of child labour or slave labour to produce goods and services for consumption in richer countries.

- Wealth and income inequality issues – both pre and post COVID-19 discussion on wealth and income inequality has been at the forefront of global economic conversations. Policy in many countries centres around the redistribution of income to assist the poor. There are moral arguments for aiming to reduce income inequality based on fairness, compassion, and generosity (virtues) to move people out of poverty and even are sometimes argued that it is in the self-interest of a country (like Covid payments to ensure economic growth does not contract significantly). This however can conflict with political rhetoric of governments creating a dilemma for decision-makers.

- Quality of life – often related to health and development economics, quality of life focuses on the ethical dilemma of how we value a life or value quality of life, especially when populations are significantly heterogenous.

Reflecting

The three ethical theories discussed in this chapter illustrate that motivations behind decision-making are complex. Cost-benefit analysis is a formalised framework for utilitarian ethics; however, it is important to consider various ethical stances in a CBA as the outcome may not lead to the appropriate decision. This is especially the case when underrepresented groups or those unable to advocate for themselves may be impacted by a policy, project, or program.

| Utilitarian Ethics | Deontological Ethics | Virtue Ethics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition |

|

|

|

| Application |

|

|

|

| Strengths |

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

Revision

Summary of Learning Objectives

- Social and ethical issues in economics are often related. Society reflects the ethics and morals of the time. Understanding ethical perspectives in decision-making enhances the results from “doing” economics.

- There were three normative ethical theories covered: (1) Utilitarianism which is most aligned with CBA and focuses on achieving the greatest benefit for the greatest number, (2) Deontological ethics is focused on whether the action is right or wrong based on rules or duties, and (3) Virtue ethics focuses on what characteristics make a virtuous person such that decisions should follow good virtues.

- The goal of this chapter was to compare the results from a utilitarian (CBA) perspective of decision-making to the alternative theories of deontology and virtue ethics. This highlights the importance of the consideration of ethical perspectives ensures that distributional impacts are appropriately identified and evaluated in CBA.

- Cost-benefit analysis is a formalised framework for utilitarian ethics. However, it is important to consider various ethical stances in a CBA as the outcome may not lead to the appropriate decision.

References

Andrade, G. (2019). Medical ethics and the trolley problem. Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine, 12.

Foot, P. (1967). The problem of abortion and the doctrine of the double effect. Oxford review, 5.

Gak, M. (2020) Opinion: Economy vs. human life is not a moral dilemma. Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/opinion-economy-vs-human-life-is-not-a-moral-dilemma/a-52942552.

Hausman, Daniel M. & Michael S. McPherson. 2006. Economic Analysis, Moral Philosophy, and Public Policy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jonsson, P. O. (2011). On utilitarianism vs virtue ethics as foundations of economic choice theory. Humanomics.

Larry, A., & Moore, M. (2021). Deontological Ethics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/ethics-deontological/

Mahler, D. G., Yonzan, N., Lakner, C., Aguilar, R. A. C., & Wu, H. (2021). Updated Estimates of the Impact of COVID-19 on Global Poverty: Turning the Corner on the Pandemic in 2021?. World Bank, 24. Retrieved from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/updated-estimates-impact-covid-19-global-poverty-turning-corner-pandemic-2021

Norheim, O. F., Abi-Rached, J. M., Bright, L. K., Bærøe, K., Ferraz, O. L., Gloppen, S., & Voorhoeve, A. (2021). Difficult trade-offs in response to COVID-19: the case for open and inclusive decision making. Nature Medicine, 27(1), 10-13.

Whitehead, M., Taylor-Robinson, D., & Barr, B. (2021). Poverty, health, and covid-19. bmj, 372. Retrieved from: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n376

- Remember that only a Sith deals in absolutes! ↵

- For additional discussion on the importance of ethics and morals in economics refer to this Conversation article: Oh, the morality: why ethics matters in economics (theconversation.com) ↵

- For further discussion see the section below on Why Does Ethics Matter to Economics in General ↵

- Ethical dilemmas are sometimes also referred to as moral dilemmas. ↵

- Metaethics is a different field where you study the nature of ethics. ↵

- Situational ethics is a whole different conversation for another time outside the scope of what is covered here. ↵

- Note: there are arguments that there are significant negative impacts that are underestimated by students including, but not exhaustive - undermining the students learning, the penalties and consequences of being caught, and reputational impacts. ↵