2 Storyteller to storyteller

Raelee Lancaster

In response to Kevin Gilbert’s 1969 essay, ‘What do I, as an Aboriginal, think about the old traditions and customs of my people, and what place do they have in present life and in the future?’

I’ve always been surrounded by storycraft. Dad loved to dance: on stage, in the living room, at the kitchen stove as he cooked his famous spaghetti bolognese. My Aunty Nick was always singing—the low lilt of her voice always echoing throughout the house—and my Aunty Lisa introduced a life-long love of Cat Stevens and Van Morrison. My Uncles were always painting. Nan would smile up at them and put their newest pieces on her mantle, as if they were kindergarteners and not fully grown men. Uncle Phil was the drama queen. He’d sip tea and spin yarns with me and my array of stuffed toys and figurines as if he were a prince and I was his little Koori princess. All this to say, storying as an artform is in my DNA.

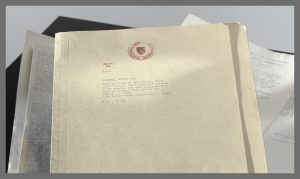

Now, as a library worker, I am surrounded by collections imbued with living story. Sometimes these collections respond, and a dialogue is opened. In his submission to the Judy Englis Essay Competition in 1969 (which resides in the Fryer Library) the late Kevin Gilbert (1933-1993) asked the question: ‘What do I, as an Aboriginal, think about the old traditions and customs of my people, and what place do they have in present life and in the future?’ Through this essay—which was submitted after, but draws from, the outcome of the 1967 Referendum—Kevin Gilbert reached into the past, wove it through present, extended it into the future, wrapped it ’round again. That is the beauty that comes from Aboriginal people crafting story.

I believe that most blackfullas have a story inside us. It sits in our bellies until the time comes to expel it. It crawls up our throats and spews forth from our lips, or floats nimbly from our fingers and limbs. It may lie dormant for months, years, decades; it may start as one thing then morph into something else entirely. The various ways story and, through it, culture, have been sustained throughout colonisation is a large component of Kevin Gilbert’s essay. He suggests that, as Aboriginal cultures continue to transform and practice evolves to incorporate our place today’s global society, we must acknowledge the past and take pride in our cultural identities—led by strong kinship practices—and collectively pave the way for a future full of Blak joy.

As the messages from this essay lingered in my mind, I thought of Kevin Gilbert’s daughter—the late Aunty Kerry Reed-Gilbert (1956-2019)—who wove incredible verse and shared her life and losses in her memoir, The Cherry Picker’s Daughter. Always willing to confront the dark and intergenerational impacts of colonisation in her work, Aunty Kerry included an element of laughter, of joy, of things to come. When I read her father’s unpublished manuscripts in the same library that housed her published works, I thought about how we—as Aboriginal people—are simultaneously the inheritors of stories, and the creators of them: always building upon that which our ancestors left behind.

I take pride in my birthright as a storyteller. It transcends nations and continents, follows me wherever I go. The Wiradjuri stories and Biripi songlines inherited from my birth father. The Gamilaraay and Biripi teachings of my (step-)Dad and our mob. The German, British and Aboriginal tapestry passed down from Mum. The Awabakal earth that nurtured me as a young person. Yagera and Turrbal Country that nurtures me now. I image a future—full of countless joys and freedoms—where I continue to craft stories, then pass them on to the next and watch them grow.

* * *

Link to the Fryer Library Collection

Kevin John Gilbert (Wiradjuri), ‘What do I, as an Aboriginal, think about the old traditions and customs of my people, and what place do they have in present life and in the future?‘, 1969, F1806, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland.

Biography

Raelee Lancaster is a writer and library professional based in Brisbane, Queensland. Raised on Awabakal land, Raelee is a descendant of the Wiradjuri and Biripi peoples, with familial ties to the K/Gamilaraay nation.

Raelee’s writing crosses poetry, nonfiction, criticism, and playwriting. Raelee’s writing has featured in The Guardian, SBS Voices, The Griffith Review, The Saturday Paper, Overland, Meanjin, The Big Issue, Australian Poetry Journal, and more. Anthologies that feature her work include Woven (Magabala, 2024), Emergence (Hardie Grant, 2023), and Fire Front: First Nations Poetry and Power Today (UQP, 2020). In 2018, Raelee was awarded first place for the Nakata Brophy Prize for Young Indigenous Writers.

Following a life-long love of history and culture, Raelee works across academic library services and heritage collections to enhance anti-colonial practice and (re)connect mob with information. Raelee began work at the University of Queensland Library in 2022 and, as of 2024, is Principal Advisor, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services and Collections. Raelee hopes to combine her creative endeavours with her library work to promote empathy, listening, and laughter in the GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums) sector.