25 A black and white history

Kealey Griffiths

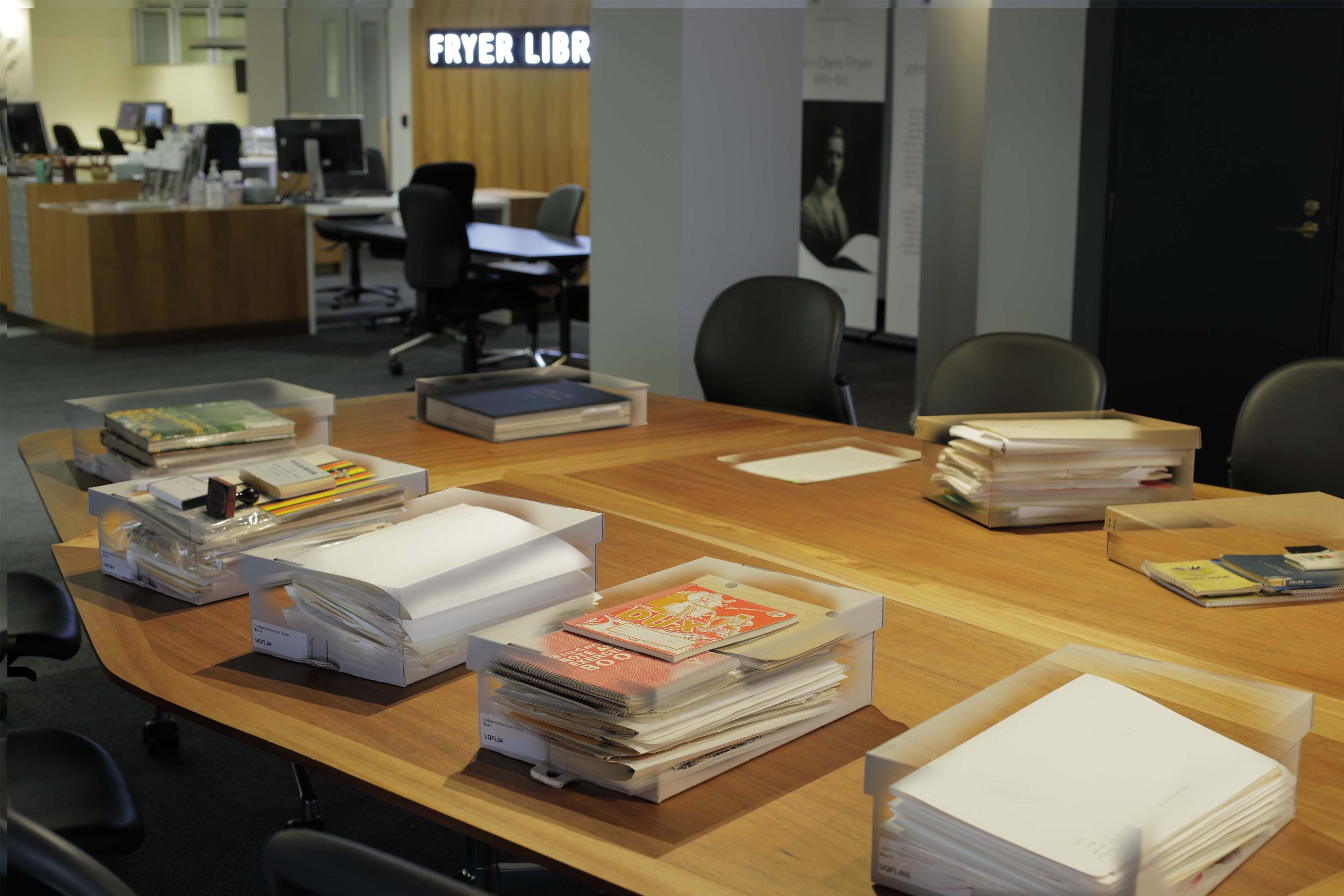

Upon walking into the Fryer Library, I was shocked by the sheer number of artefacts laid out on the tables, only to be reassured, ‘There is heaps more I can get out for you if you don’t find anything’. Every piece, from posters to manuscript drafts to photographs, contributed to the overwhelming and all-consuming feeling that I didn’t know enough about my history, family, and mob.

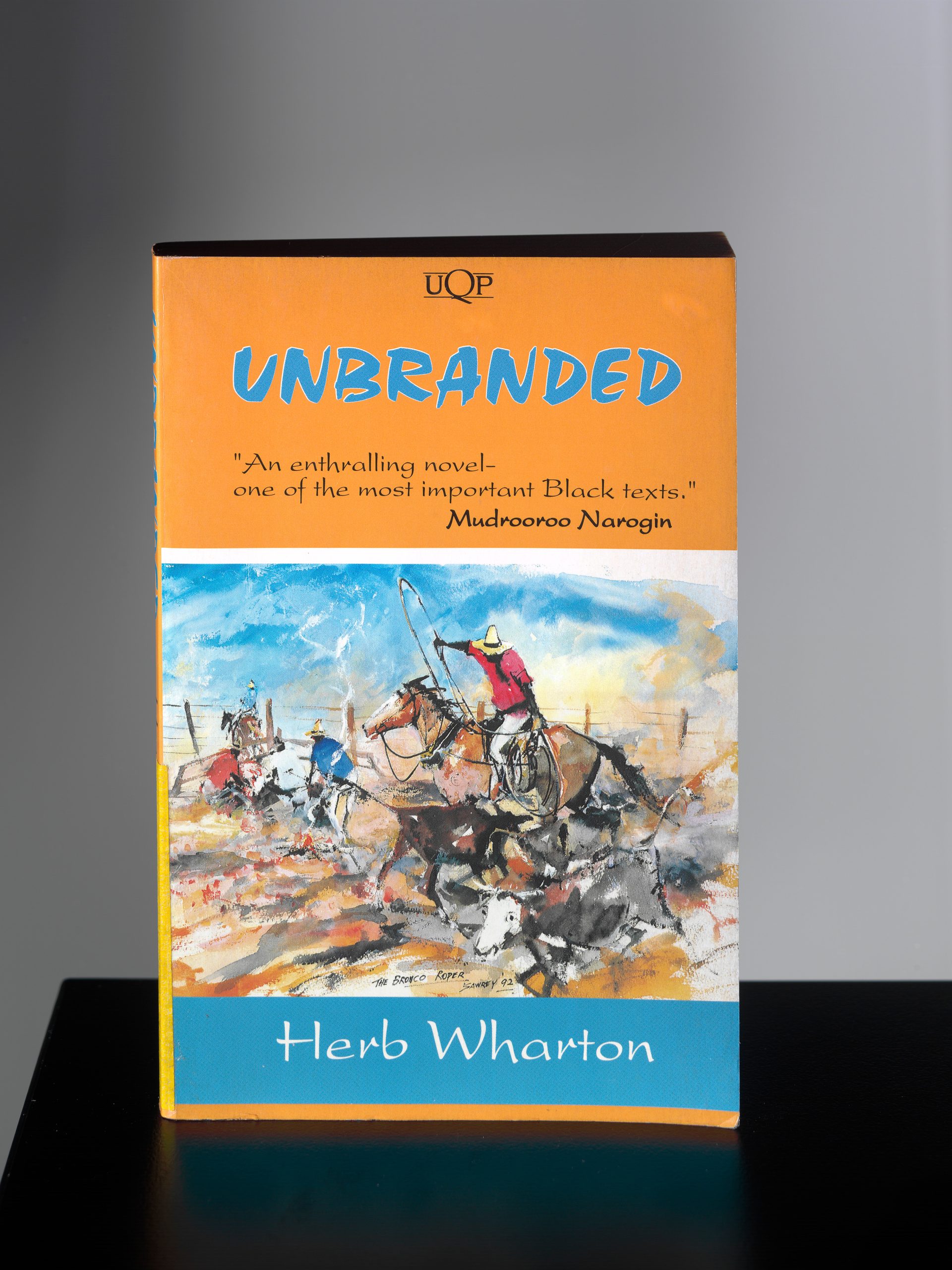

After looking through dozens of posters on table one, I moved to Herb Wharton’s collection of photographs. I flicked through each page, taking in the images one by one and I felt myself smiling as the album took me on a journey of his travels – through Australia, then France and what appeared to be somewhere in South-East Asia.

The photograph that caught my eye immediately was one of a dry landscape and a blue sky, dotted with wispy clouds. It was neither the land or sky that drew me in – it was the Southern Cross Windmill.

Over 150 years ago, Mr. George Washington Griffiths of Bristol, England, established an ironmongery and mechanical repair shop in Toowoomba, Queensland. Named after himself and his brother, Griffiths Bros. & Co would go on to produce the Southern Cross Windmill.

Mr G. W. Griffiths is my paternal great-great grandfather and I seem to know more about him (and why three legs on a windmill is better than four) than I do about my maternal grandfather, let alone my maternal great-great grandfather.

My maternal grandfather, Norman ‘Wally’ Watson, a Yuggera man, passed away before I was born, but through stories from my mother and Nanny, I have come to know a warm-hearted and cheeky man, who loved his family dearly and worked hard to get what he had.

Wally was born in 1953 to older parents, who had already had numerous children and were living in Killarney, Queensland. His father, Alexander Hugh Watson, and his grandfather, would have been alive during the establishment of Griffiths Bros. & Co in Toowoomba. Killarney is just over a 90-minute drive from Toowoomba, but I know the lives of the Watson and Griffiths families would have been so incongruous that neither would have been able to look forward and expect the union of my mother, Tina Watson, and father, Justin Griffiths in 1994.

The passing of Wally when my mother was a very young woman exacerbated the disconnection from culture that began when he was put into the custody of the state as a child. And at no deliberate action of my own (or my parents, or grandparents), what I know about my family history is predominately white. This isn’t shocking, or at least shouldn’t be. Australia’s history books and teachings are white and there has been little to no inclusion of Indigenous voices and knowledge since the invasion of Australia.

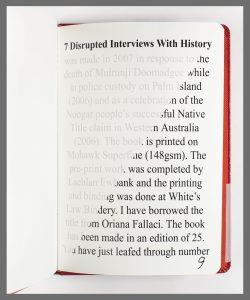

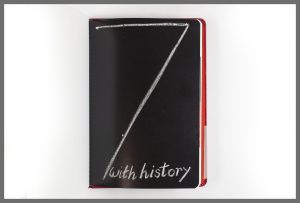

This sentiment was brilliantly captured in 7 Disrupted Interviews with History by Peter Lyssiotis. The seven chapter volume, bound in a brilliant red leather, features very few words and instead, the story is shared through photographic collage.

The heading page for the seventh chapter, ‘With History’, is written in chalk on a blackboard, evoking memories of my country pre-school classroom, before they updated to whiteboards. Before turning the page, I felt I was in for a lesson and that was quickly confirmed when the next page was blank. Completely white. Just like the history books and teachings of Australia.

With age, and exposure to brilliant and insightful Elders and communities, I have learnt more about my culture and family history. Unfortunately, neither my mother, sister, or I will be able to gain the wealth of knowledge that I know Wally and his family could have shared had things not happened the way they had. This loss of intergenerational knowledge is not a unique experience and is faced by the majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, hence stressing the importance of giving Indigenous voices and Traditional Knowledge a platform.

* * *

Links to the Fryer Library Collection

Herb Wharton (Guwamu/Kooma), ‘[Southern Cross Windmill]’, (undated), Herb Wharton Papers, UQFL212, Album 1, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland.

Lyssiotis, P. (2007). 7 disrupted interviews with history. Masterthief.

Biography

A Yuggera (Jagera) woman who grew up in Western Queensland with my parents and younger sister, I love reading and always have up to five different books on the go. Current reads include Deja Dead by Kathy Reichs, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

I have been working and studying at UQ since graduating high school in 2018 and will graduate with a Bachelor of Science. While still early in my career, I have worked on various projects around the university pertaining to my passions – Indigenous and women’s health and human rights. I work as a Cultural Mediator at the UQ Art Museum and as a Research Assistant in the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences. In my research assistant role, I work alongside Mr Jim Walker, a Jagera, Yiman and Goreng Goreng man. Our work surrounds Traditional Knowledge, and I am currently assisting in the development of a new elective course for second-year science students — Centring Traditional Knowledge in Science.

Beyond UQ, I work as a consumer representative and advocate within health organisations to make meaningful and systematic change, especially for Indigenous Australians and young people. On top of work and full-time university, I am studying a Cert II in Auslan and want to attain a Diploma of Auslan. After graduating, I plan to study medicine, with hopes of leveraging my complementary skills in Auslan and consumer representation to make healthcare more accessible and inclusive.