1 Decolonising the archive

Mia Strasek-Barker

As a younger black woman who recently came to work in the GLAM sector (Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums), I define it as deeply embedded in the colonial project, in that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander records are rarely told through a narrative of their own.

Our people seeing, listening to, reading and feeling historical records daily do so from the colonisers’ point of view. A view that was entrenched in conquering and sought to exclude, silence, extinguish and erase sovereignty and diminish our historical accounts and narratives.

Those records can be biased, racist, offensive and insulting, or simply untrue, and their contents often do not reflect the lived experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This point of view did then and continues today to have detrimental impacts on our social and emotional wellbeing. The whole process is confronting for us. Yet I assert that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander records are alive and well and require current use, as I come from the oldest living culture in the world. This is an immediate tension point with the Western definition of an archive.

We know that cultural institutions play a pivotal role in the Western notions shaping our understandings of the histories, knowledges, and stories of places and peoples. Galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAMs) are often described as guardians of cultural heritage material, responsible for collecting, describing, evaluating, exhibiting, and preserving cultural and environmental material to ensure lasting value to the organisation or public they serve.

My definition would seek not to exclude the complexities inherent in that work.

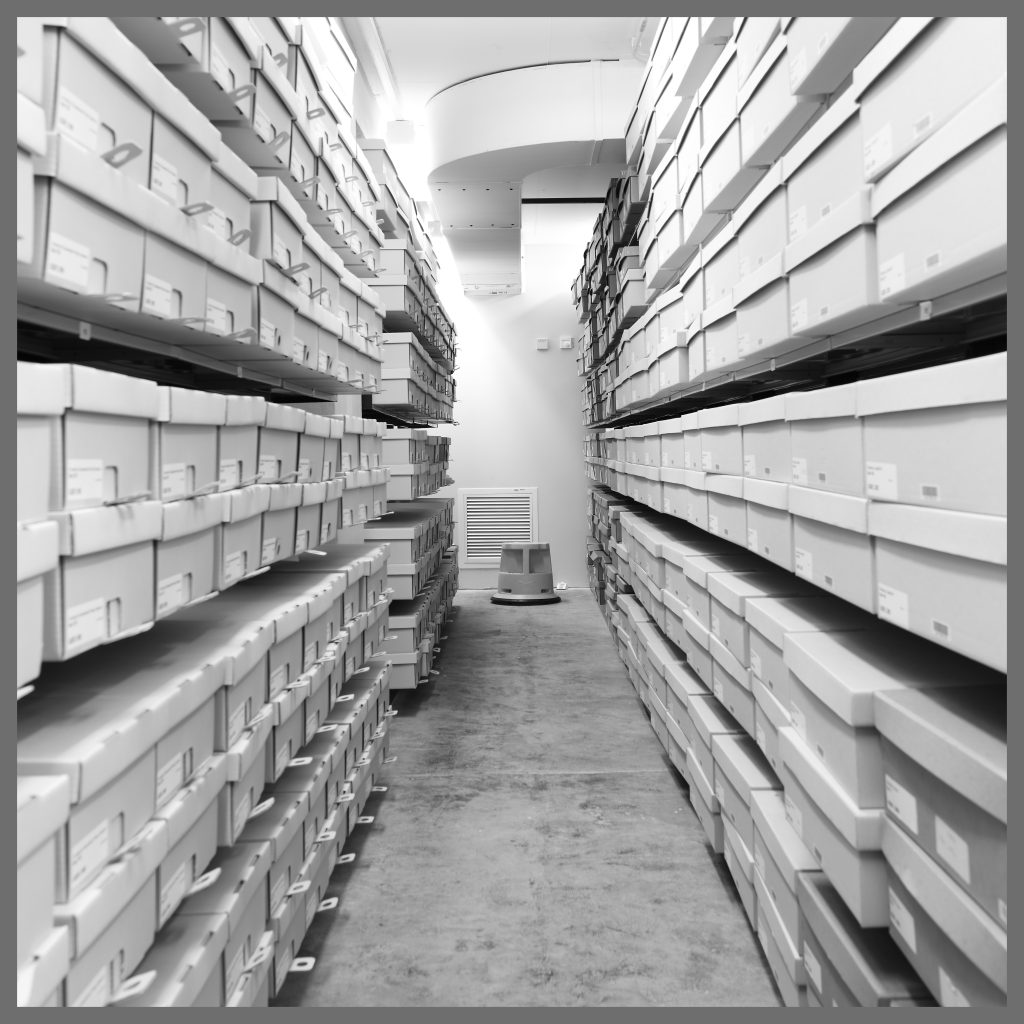

The GLAM sector is built from the colonial project; therefore, systematically, there are significant power imbalances, centred around privilege and discriminatory practices, that continue to exclude First Nations knowledges and perspectives. This is evident not only in the destruction of some records and materials, but in the metadata and information systems and technology we use, that is not user-friendly for our mob.

It is a painful experience for mob to see a lack of care around records being created, maintained and preserved. In centering and lifting voices of mob, you should be reading and considering the works of Rose Barrowcliffe1, a Butchulla researcher from the University of the Sunshine Coast; Kirsten Thorpe2, a Worimi woman and senior researcher out of the University of Technology, Sydney; and Nathan Sentence3, a Wiradjuri Librarian working out of the National Australian Museum to name some vocal, passionate and educative individuals in this sector.

With this in mind, how do we take back the narrative and challenge the colonial legacy and tell our own stories using materials in galleries, libraries, archives and museums?

We must first centre Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to know what records and material are available that relate to them, to Country, to family – and create space for them to tell their own story, their own narrative, and their own interpretation of the items and materials.

When Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are able to enact this, the longstanding perception that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and peoples are only objects of history or studies for anthropology, rather than sovereign human beings with a voice and knowledge of their own, is challenged.

For example, this is done very well by sister Megan Cope4 (of the proppaNOW Collective) who uses historical accounts from the GLAM sector to influence her artwork and either flip the dominant narrative, or expose a narrative that may be lost in warehouses and filing, if it is not perceived as important to highlight or showcase by those in power (ie the decision-makers) at these institutions.

Megan asserts her identity as a sovereign Quandamooka woman. This is evident through themes in her artwork. She has cultural responsibility to the environment and is socially concerned about its fragility since colonisation.

The idiom ‘dead wood’ refers to people or things that are no longer useful. Megan criticises existing political agendas promoting mining and agricultural development over environmental protection, an issue of personal interest affecting her island home of Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island). In this installation5, large sheets of paperbark are hung from the ceiling, etched with significant information regarding cultural heritage of land and sea management.

Acting as a condition report, the work rightfully centres the Traditional Owners as landlords and the paperbark scrolls as a recognisable environmental assessment. Government and historical records frequently express the abundance of resources prior to colonial occupation of Australia. Deadwood acknowledges this pre-colonial history, the traditional sustainable practices of Aboriginal people, and their role as custodians and ongoing caretakers of Country.

Megan brings this information to light, presented in a way that connects to us mob, based on the importance of Country. Would this narrative be told otherwise if Megan and other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists, communities and individuals were not challenging the status quo? She is testing and truth telling at the same time with the use of historical GLAM records and materials.

Megan’s installation is reminiscent of the Yirrkala Bark Petition6 which, on 14 August 1963, was presented to the Australian Parliament’s House of Representatives. It was the first ‘formal’ assertion of Indigenous native title.

In February 1962, the Australian Government gave authority to a Swiss company to mine Bauxite near Yirrkala. The first time the community became aware of this was through the ABC news. Isn’t it telling that Megan’s contemporary work based on issues of cultural heritage destruction are so prevalent today, with such examples as the Wiradjuri Elders fighting against a new proposed go-kart track7 on a significant cultural site or the destruction of Juukan Gorge at the hands of Rio Tinto8, which the Bark Petitions and their creators sought to address in the 1960s.

I wonder how seeing, hearing and reviewing these records made Megan feel during her creative process. Did Megan have emotional and physical reactions to the devastation and changes affecting her Country since colonisation and more recently with the sand mining.

I can only speak to my experience of working with historical material.

Recently, as part of an audit process, I reviewed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander material related to missionary paperwork. This included such things as images, maps, language transcriptions and, most appallingly, mission management correspondence.

These records sparked a physical reaction within my body. I was expecting emotions and feelings to surface, feelings of sadness and anger, but came to find out exactly how this trauma latches on to your body physically. You become tense in your neck and shoulders without realising how your body is acting as barrier of protection to these pieces of paper or images that are held by the sector. Mum said to me that the Western frame of mind is to feel with the heart, whereas we mob feel with our gut. This is why mob follow our gut instinct and get sick in the stomach – something I encountered. From these historical records, I experienced a collective pain, as the materials I was working with were not from my own Country or family.

These experiences and discussions of discomfort and trauma in the GLAM sector rarely happen with non-Indigenous colleagues. Rather Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people debrief with each other about critical topics that are at odds with Western frameworks and process. This includes things like:

- where and how we keep items

- how we classify, describe and give in/correct voice to cultural heritage collections

- the confusion of accessing items

- the fine line between assisting and recording so as not to perpetuate trauma

- and lastly, what we celebrate in the GLAM sector, to some of our people, is oppressive and divisive; like when the Australian Government announced a package of measures to mark and celebrate the 250th Anniversary of James Cook’s first voyage to Australia and the Pacific in 1770.

Moving forward, it is time for another group to feel the harsh discomfort that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have grappled with since colonisation and the white-washing narratives that dispute our truth-telling. For non-Indigenous peoples, instead of taking up the position: ‘Why are you (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people) making me feel uncomfortable?’, you must shift your thinking to: ‘Why do I feel uncomfortable?’ when engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories and histories. It is after all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who live with these physical, emotional and spiritual discomforts every day since the colonial ‘discovery’.

Powerful things can happen when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people engage with the sector and content in a culturally safe way.

I will end with a family yarn about great grandfather, Jimmie Barker9, and the idea of how appropriate collection management can enable mob to speak back to historical records and material. Grandfather Jimmie was the first known Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Australian to use recorded sound as an instrument to preserve and record Aboriginal culture (as early as the 1920s, he recorded King Clyde of the Barwon Blacks) giving awareness and appreciation to Muruwari and Ngemba life.

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) has been collaborating with family members and reviewing the recordings he made in the 1960s, which had been deposited by non-Indigenous anthropologist Janet Mathews. The aim was to appropriately acknowledge Grandfather Jimmie for parts of the collection that were wrongly credited as being Mathews’s work. Once the review process was complete, it was determined that not only should Jimmie Barker be named as the creator of these works, but other associated rights (for example, Indigenous cultural and intellectual property rights) be attributed to Grandfather Jimmie for many of the recordings.

It became evident that Grandfather Jimmie Barker, with his brother Billy, had independently developed a technique to make sound recordings, without prior knowledge of the work of Thomas Edison and others in the development of sound recording technology. The collection materials have been found to include detailed descriptions of their experiments, with their first successful recording taking place in 1909.

In keeping with the right to know and right to reply process (which helps give agency and self-determination), AIATSIS invited my Uncle Roy Jnr to present at the Alice Moyle Memorial Lecture in 2019 at the Australian Sound Recordings Association Conference in Canberra. This was the first public revelation of Jimmie Barker’s claim to have invented sound recording in Australia. It caused quite the controversy, potentially rewriting the history of sound recording, which is truly thought-provoking and hard for some to consider. This revelation only confirmed or proved something that us mob already deeply know and feel – that we and our ancestors have been proppa smart and proppa deadly all along!

References

- Dr. Rose Barrowcliffe, (n.d.). Research.

- University of Technology Sydney. (n.d.). Kirsten Thorpe.

- Sentence, N. (n.d.). How to provide access without causing harm? National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

- Megan Cope. (2024). Megan Cope.

- Megan Cope. (2024). Deadwood.

- National Museum of Australia. (n.d.). Yirrkala Bark Petitions.

- NITV. (2020, November 24). Traditional Owners to Continue Fight against Proposed Go-kart Track.

- ANTAR. (2023, December 11). The destruction of Juukan Gorge.

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. (2023, July 27). Pretty little lines – Jimmie Barker sound pioneer.

* * *

Biography

A proud Gamilaraay Woman from Lightning Ridge in New South Wales, Mia Strasek-Barker is Senior Manager, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services and Collections at UQ Library. Prior to that, Mia worked closely with the Office of the Pro-Vice Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement), UQ Community and external communities to ensure UQ’s diversity and inclusion values meaningfully contribute to implementing UQ’s Reconciliation Action Plan. She devotes her energy to progressing the aims and vision of the UQ Strategic Plan and the Library Strategic Plans, coordinating and managing a range of activities and events across UQ to highlight the Library’s acknowledgement and commitment to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples through its collections and services. Before coming to UQ, Mia worked at the Australian Indigenous Education Foundation (AIEF), where, as Regional Pathways Manager, she was responsible for overseeing the AIEF Program in Queensland and Western Australia. Mia has also worked with CareerTrackers as National Partnerships Manager.