6 Research is no holiday

The importance of honesty, reflexivity, and community engagement

Abraham Bradfield

As an early-career non-Indigenous researcher educated in field of anthropology, I chose to reflect on the Norman F. Nelson Collection as its preamble ‘Brisbane to Burketown’ reminds me of the ‘entering the field’ accounts so richly documented in countless ethnographies and monographs. In this collection, we read of Nelson’s journey, his mode of transportation, timetables, transits, the food he consumes, and the interactions he encounters. He is travelling alongside his companion, J.T Robinson, whom we are told ‘had not had a holiday for several years’.

Nelson’s writing communicates a sense of adventure and discovery. As social scientists who often study cultures different to our own, the same sense of adventure by entering the world of the so-called “other” continues to feature in much of our work. Seminal Indigenous scholars such as Professor Lester Rigney, Distinguished Professor Aileen Moreton-Robinson, Professor Bronwyn Fredericks, and Professor Martin Nakata, amongst others, remind us that the political implications, the standpoints from which we write, and how we represent ourselves and others must be scrutinised so that deficit and reductionist representations of Indigenous peoples do not continue.

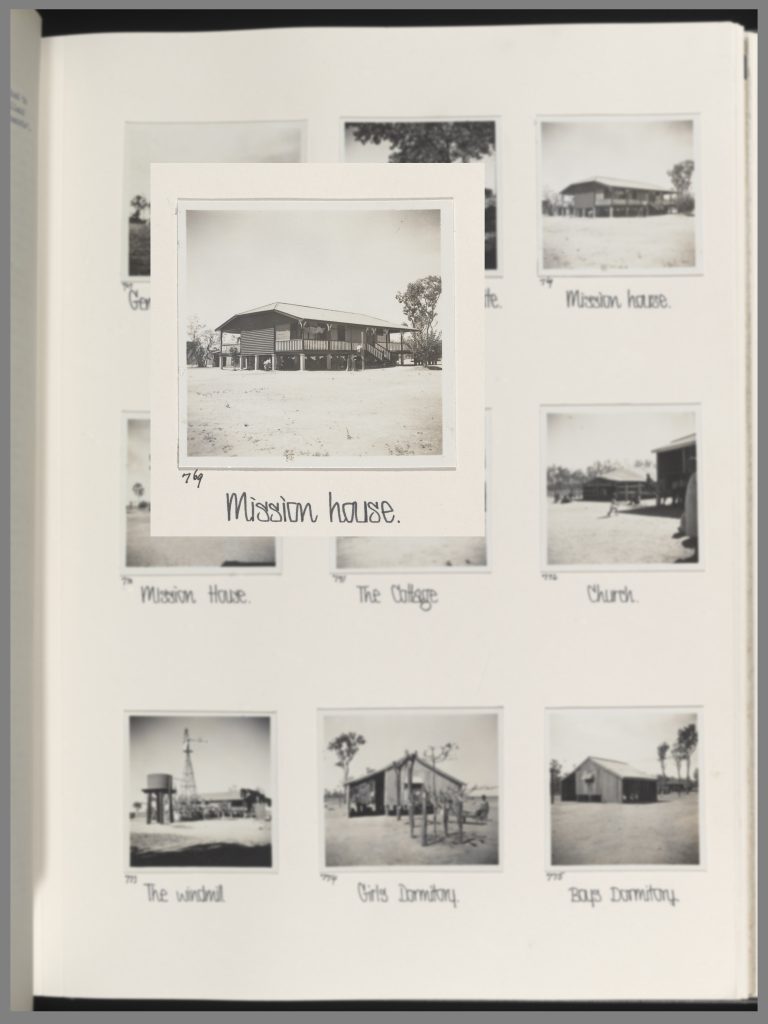

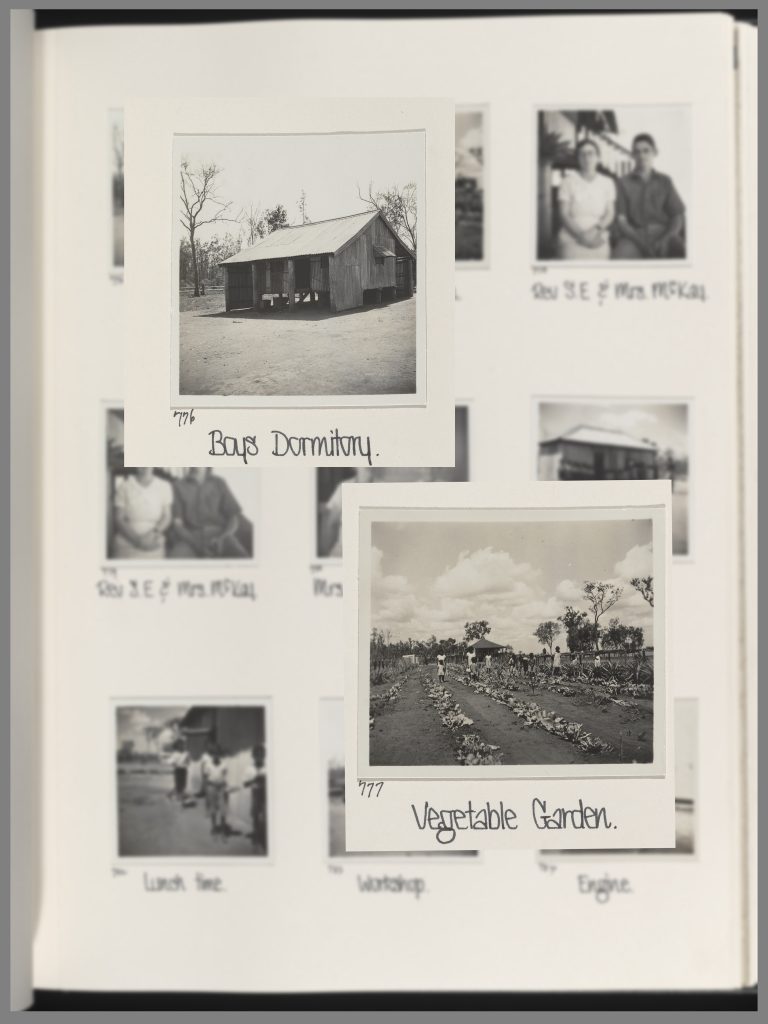

The Norman F. Nelson Collection functions as an inventory that documents his ‘inspection and evaluation of work and properties’ of missionary compounds in Queensland during the 1930s. Commissioned by the Presbyterian Church, the collection provides an overview of the infrastructure, layout, conditions, dimensions, plots for growing food, and other indexes that are used to assess if the Church is gaining a ‘return of investment’ (my words, not theirs).

The series of photographs of the Aboriginal inmates that follows the preamble provides a rich (albeit censored and sanitised) historic account of daily life on the mission. The photographs visually represent activities such as fishing and farming, but also include more invasive activities such as girls bathing. While Nelson names some of those he interacts with (a practice not always followed in ethnographic records), the power to decide who and what should be documented lies entirely at his discretion. In the eyes of the mission and colonial state, the Aboriginal inmates remain ‘property’, and like the houses and infrastructure, require management and upkeep.

It is easy to condemn such writing as paternalistic products of their time – disturbing yardsticks through which we measure just how much Australia has now ‘progressed’ and ‘advanced’. This was the 1930s after all, and the controlling policies of the assimilationist era are no longer publicly acceptable. What is harder to confront, however, is the possibility that through our scholarly writings (and informal discussions) we are potentially complicit in the very same paternal acts of labelling, categorising, and dehumanising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

This collection forced me to consider the purpose of research, and more importantly, interrogate who we are doing research for. Social scientists build their careers on interacting with people – not passive or voiceless properties. Our words and actions have real and lasting impact on the lives of others and should never be presented as mere inventories. Research and fieldwork with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should not be characterised as a ‘holiday’ – a moment of intervention before returning home – but rather should assure community involvement and ownership with aim of creating lasting positive change.

* * *

Link to the Fryer Library Collection

Norman Francis Nelson, ‘Brisbane to Burketown report’, 1936, Record of visit to mission stations, UQFL57, Series B, Item 1, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland.

Biography

Abraham Bradfield PhD was a Research Officer with the Office of the Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement) at the University of Queensland. He now works at the University of Sydney as a Research Officer. Grounded in Anthropology, Social Sciences, and Critical Indigenous Studies, Abraham applies a cross and transdisciplinary approach to his research to explore themes relating to colonisation, identity, and the intercultural. He remains committed to developing and implementing morally responsible research that challenges colonial power structures and encourages new habits of thought and praxis.