19 Response to Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s poems

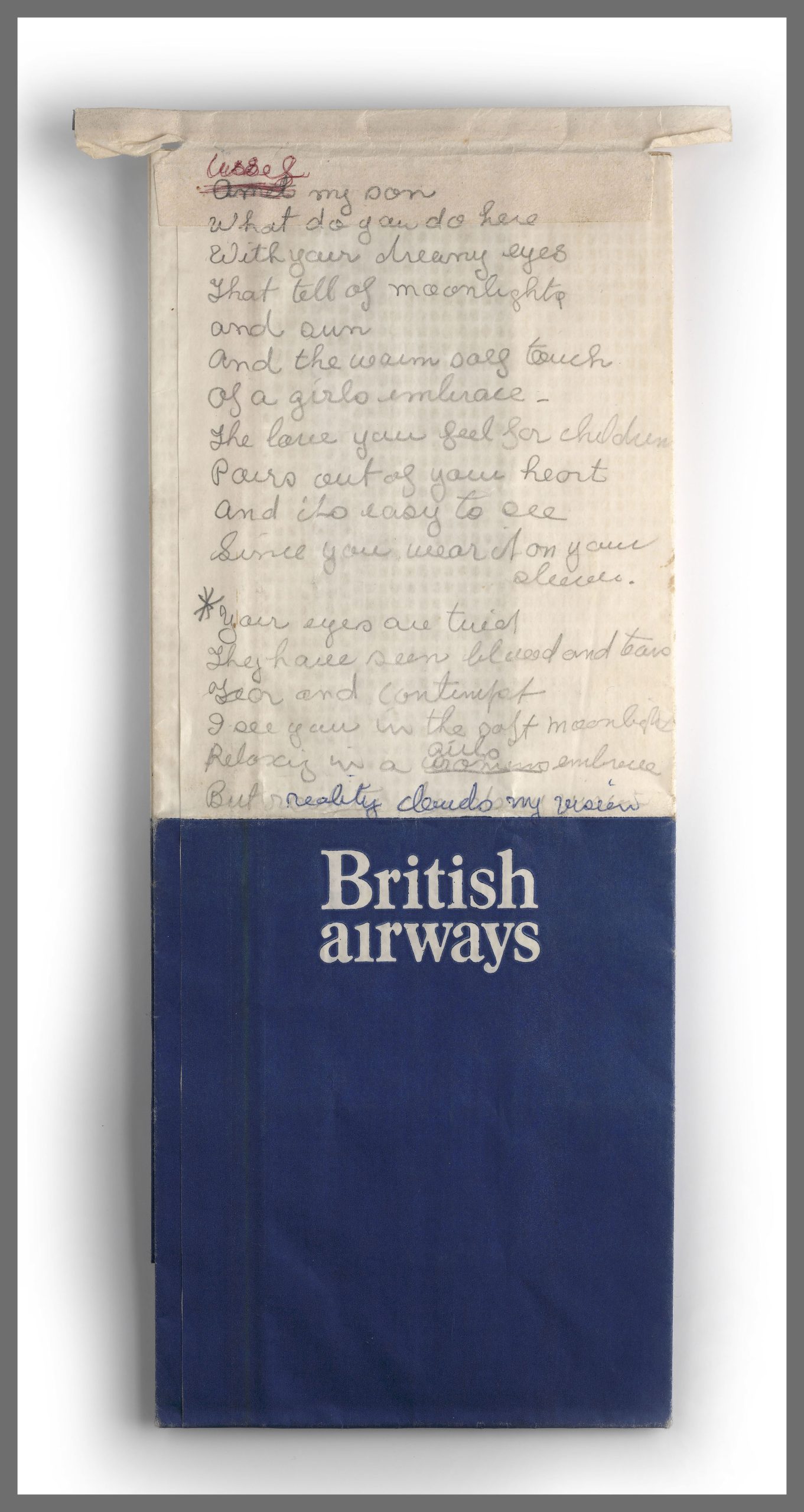

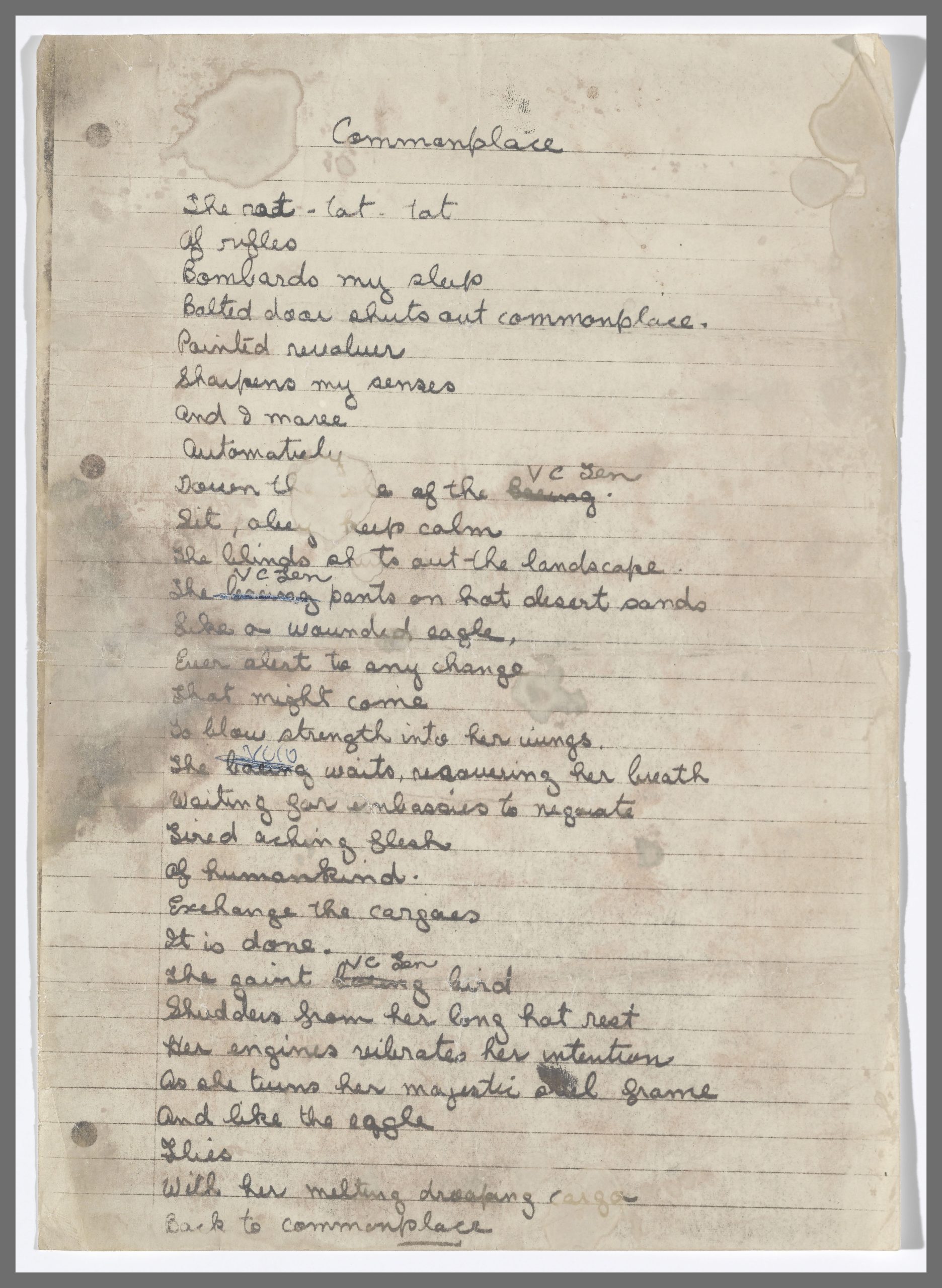

Commonplace and Yusuf (Hijacker) written on a British Airways sickbag, 1974

Bronwyn Fredericks

On the 21st of November 1974, Aboriginal poet Oodgeroo Noonuccal was returning home with two colleagues, John Moriarty and Chris McGuigan, after attending the World Black Festival of the Arts in Lagos, Nigeria. During a stopover in Dubai, the British Airways plane was hijacked by Palestinian terrorists who over three days held the passengers hostage – executing a flight attendant and German banker. In a situation marked by anxiety and increasing tension, Oodgeroo Noonuccal wrote her thoughts in poetry on the materials available to her at the time – a blunt pencil and a sickbag. The two poems produced by Noonuccal were Commonplace and Yusuf (Hijacker) which can be seen in the Fryer Library’s collection at The University of Queensland (UQ).1

A version of Yusuf (Hijacker) was published in the UQ student newspaper and both poems were published in a collection of her works in 1981. Despite expressing that she was not fearful of losing her life – for she had already lived what she described as ‘five lifetimes’ – the experience, particularly the execution of the banker, haunted Oodgeroo Noonuccal until her death on the 16 September 1993 at the age of 72.2

Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s experience on that fateful flight caused memories of Country and place to re-surface.3 The experiences we have with and within place can quickly transport us to seminal moments in our lives, whilst potentially creating new memories and life trajectories. This is regardless of where we are in urban, regional or remote localities or where we are travelling.4 As an Aboriginal woman living in colonised Australia, Oodgeroo Noonuccal had a particular set of experiences. She also demonstrated through her writing that because of these experiences, she had some sympathy towards the Palestinians people’s fight for social justice.

Her son Denis Walker and nephew Sam Watson were both involved in establishing the Black Panther Movement in Brisbane, Queensland. I remember them both and was on the Link-Up (Qld) Board with Sam for years. While the Black Panthers were far from a terrorist organisation, they did encourage what some would see as militant approaches to social justice, a point which differed from Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s preference for peaceful reconciliation and non-violent forms of activism.2 Noonuccal nonetheless was able to empathise with how anger, disempowerment, and the dehumanisation of certain ethnicities could drive some to take up arms, a subject she explores in her poem Yusuf (Hijacker) and her article in Semper Floreat, the UQ student newspaper.3

Whilst held captive, Oodgeroo Noonuccal shared stories of Aboriginal people’s own disempowerment in attempt to create rapport with the hijackers in hope of dissuading them from further violence.3 The event brought memories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s ongoing experiences of social injustice. After Noonuccal descended the plane upon the successful negotiation of her and some other passenger’s release in Tunis, she was transported by a Black Maria, the same vehicle used by Queensland Police to transfer (disproportionally Aboriginal) prisoners; this irony was not lost on Oodgeroo Noonuccal.

Memory and place however are also sources of comfort and strength. As water was fast depleting – reported to be limited to two tablespoons per hour – Noonuccal’s memories transported her to her homeland on Quandamooka Country and the abundance of life provided by Country. This was a source of strength that she shared with the other hostages, which provided reassurance and hope.2 It is also a strength carried through the works of Quandamooka artists like Delvene Cockatoo-Collins, Sonya Carmichael, and Elisa Jane Carmichael.

The irony of the poems being written on a sickbag should also not go unnoticed. Colonisation across the world – whether in Australia or Israel/Palestine – has created what Brendan Hokowhitu describes as a state of ‘dis-ease’, a discomfort or sickness that comes from the exhausting (albeit necessary) need of subjugated peoples to push back against the forces of hegemonic oppression, and the stereotypes and misinformation5, 6, 7.

I chose to reflect on this item of the Fryer Library’s Indigenous Collection as Oodgeroo Noonuccal encapsulates the strength and endurance of the Black women and men who continue to triumph in the face of social upheaval. Strength I aspire to replicate in all my work and roles, including in my role as Pro-Vice Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement) at UQ. As she brilliantly achieves in these two poems, Noonuccal forces us to confront the truths of history and our actions in all its beauty and sickening horror, much in the same way that her Country woman Aileen Moreton-Robinson does in her scholarly books The White Possessive and Talkin’ Up to the White Woman, and Megan Cope does through her many artworks6, 8, 9, 10. Collectively, these powerful women encourage us to seek deeper understandings of our shared humanity as means to reconcile differences and purge ourselves of the nauseating hate and anger that continues to create our dis-ease.

References

- Walker, K. (1981). My People. A Kath Walker Collection (2nd ed). Jacaranda Press.

- Watson, S. (2001, March 14). One Dreaming Stilled [Interview]. Encounter; Radio National.

- Walker, K. (1975). Hi-Jack, Semper Floreat, 45(2), pp. 8-9.

- Fredericks, B. (2013). ‘We don’t leave our identities at the city limits’: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in urban localities, Australian Aboriginal Studies, 4-16.

- Hokowhitu, B. (2014). If you are not healthy, then what are you? Healthism, colonial disease and body-logic. In K. Fitzpatrick & R. Tinning (Eds.), Healthism, colonial disease and body-logic, Health Education: Critical Perspectives (pp. 31–47), Routledge.

- Fredericks, B. and Bradfield, A. (2021a). ‘Waiting with bated breath’: Navigating the monstrous world of online racism. M/C Journal, 24(5).

- Fredericks, B., Bradfield, A., McAvoy, S., Ward, J., Spierings, S., Combo, T. and Toth-Peter, A. (2022). The Burden of the Beast: Countering Conspiracies and Misinformation with Indigenous Communities in Australia, M/C Journal, 25(1).

- Moreton-Robinson, A. (2015). The White Possessive: Property, Power and Indigenous Sovereignty. Minnesota Press.

- Moreton-Robinson, A. (2000). Talkin’ Up to the White Woman: Indigenous Women and Feminism. University of Queensland Press.

- Fredericks, B. and Bradfield, A. (2021b). ‘I’m Not Afraid of the Dark’: White Colonial Fears, Anxieties, and Racism in Australia and beyond, M/C Journal, 24(2).

* * *

Links to the Fryer Library Collection

Oodgeroo Noonuccal (Moondjan), ‘Yussef (Hi-jacker)’, 1975, Oodgeroo Noonuccal Papers, UQFL84, Series A, Subseries 1, File 1, Item 25, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland.

Oodgeroo Noonuccal (Moondjan), ‘Commonplace’, 1975, Oodgeroo Noonuccal Papers, UQFL84, Series A, Subseries 1, File 1, Item 26, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland.

Biography

Professor Bronwyn Fredericks is an Aboriginal woman from SE Queensland and Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement). She has held leadership roles in federal and state government and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-based organisations, and worked as an educator in secondary schools, TAFE, and universities. Bronwyn holds qualifications in education and health, is a past recipient of NHMRC, Endeavour and research supervision awards, and remains active in research into Indigenous health, wellbeing and education with a practice-based commitment to improving life outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. She is a passionate advocate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights, and was a member of the Uluru Statement From the Heart Working Group and an active campaigner during the 2023 Referendum for a Voice to Parliament. She is an affiliate with UQ’s Poche Centre for Indigenous Health, Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences. See: Professor Bronwyn Fredericks’ ORCID and UQ Experts profile.