18 The story behind the paintings

Goobalathaldin Dick Roughsey’s The Rainbow Serpent

Terrence Wright

The question that needs to be addressed is: What does this item evoke for you? The first two things that I need to do then is to address what ‘evoke’ means and explain my item.

Doing a simple Google word search, ‘evoke’ is defined as ‘to bring or recall (a feeling, memory, or image) to the conscious mind’ or ‘to elicit a response.1

It is the second meaning that I will be focusing on in order to address the question.

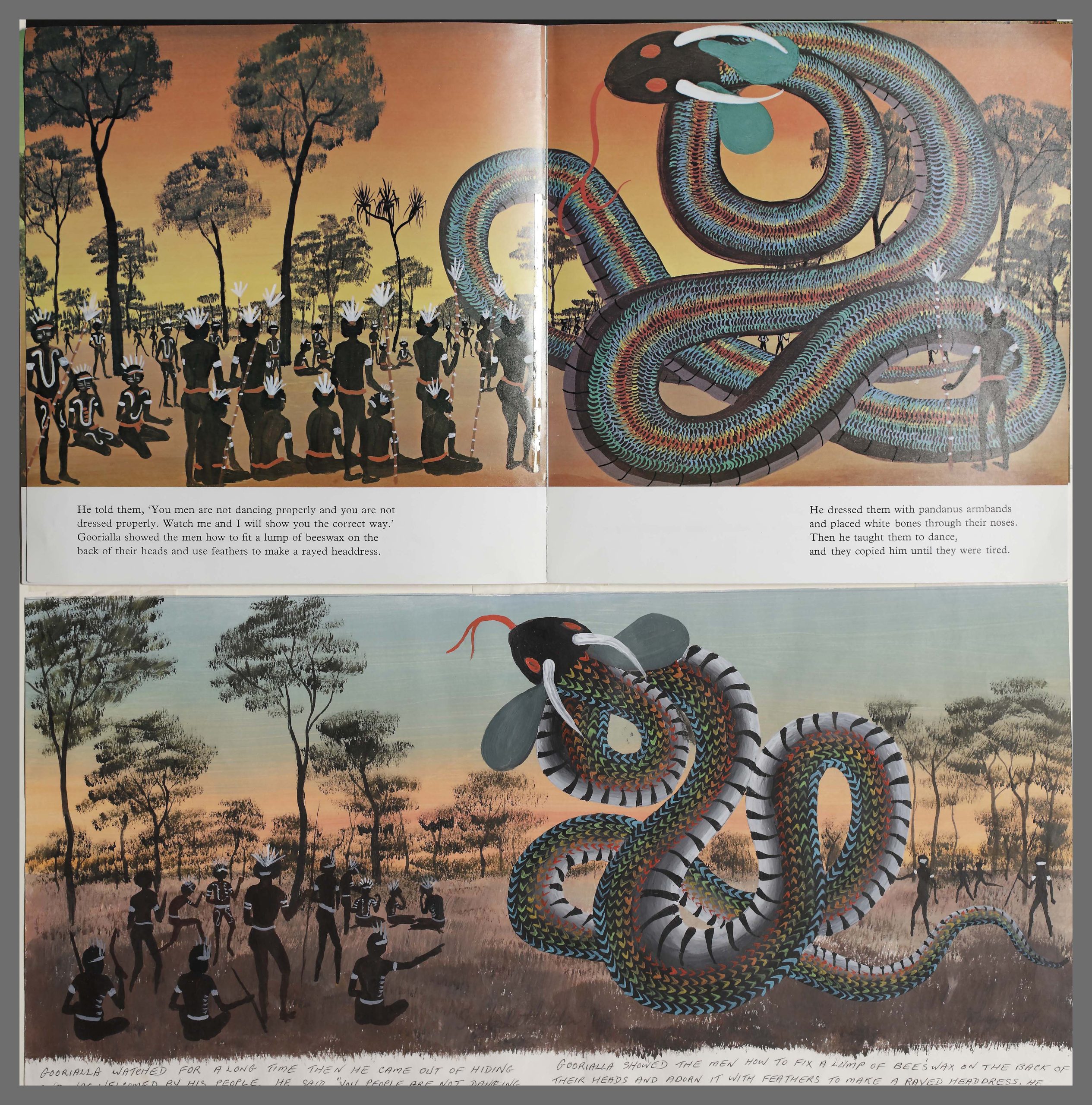

Now to the item I chose. These items are just some of the original paintings that led to the production of The Rainbow Serpent by Goobalathaldin Dick Roughsey. Goobalathaldin was born on Mornington Island in 1924 and passed away in 1985. The Rainbow Serpent is his best-known work, first published in 1975, and it remains in print today. Probably the great majority of Australian primary school children would at least have been read the story, or if not, they have read it themselves.

Roughsey met Percy Trezise, a non-Indigenous pilot who worked in remote areas of northern Australia and they developed a strong, to the point that Tresize became a collaborator on projects and a mentor for Goobalathaldin’s career development.

The first response evoked by the paintings was admiration for Goobalathaldin’s use of colour, shading and light, and the overall style of the paintings. They are visually stunning!

The second was the memory of reading The Rainbow Serpent to (some of) my children. And not only reading it to my children but using the book in primary classrooms in which I have worked. It is that instant recognition of the book when young people are asked the question, ‘Do you know the Rainbow Serpent story?’ My experience tells me that the majority of children can respond positively, and further, they can recount the story.

The third response evoked by the paintings, and the one of most interest, though, was comparing the paintings to the images in the printed book. Several differences appeared, and thus the questions of who made the changes and why came to the forefront. Of course, these questions are not easily addressed and require further research.

The differences were as diverse as changes to the colour palettes; the layout of the painting, including the focus, was altered; and in some paintings, the content itself was modified.

For example, in the above images, the top image is the publication version. The second image is the original painting with the handwritten story.

My interpretations of the two images are purely based on layperson observations, but as stated earlier, the questions of who made the changes and why remain. My observations include:

- the ceremonial markings and attire of the people represented

- the Rainbow Serpent itself is coloured differently with more rainbow

- the colour palette in the published version is quite a bit brighter than the painting which is darker in its imagery

- the foliage on the trees is quite different – more stereotypical leaf-like representation

- the foreground in the publication version is ‘cleaner’, devoid of vegetation, as opposed to the painting, which I would suggest is more realistic, and

- the overall layout or design of the painted version is such that it is composed with half of the image taken up by The Rainbow Serpent and the other half by the people and the trees.

It was an honour to be able to not only see but hold the original paintings from Goobalathaldin Dick Roughsey and understand the legacy that this work has left, not only for Australian schoolchildren, but also for a much broader Australian audience, and quite possibly, an international audience as well. A much more detailed analysis of these works would not be out of place as a research project at UQ through the Fryer Library.

References

- Google (n.d.) evoke meaning.

* * *

Links to the Fryer Library Collection

Roughsey, D. (Lardil) (1979). The rainbow serpent. Collins.

Goobalathaldin Dick Roughsey (Lardil) and Percy Tresize, ‘Goorialla watched for a long time then he came out of hiding and was welcomed by his people’, 1974, Papers of Dick Roughsey and Percy Tresize, UQFL386, Series D, Item 6, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland.

Biography

Terrence Wright is a member of the Yuin Nation, Jerringa and Badawang clans, having been born, bred and schooled in Nowra, New South Wales. He has worked in a number of universities for over 30 years primarily in NSW and the Northern Territory. He holds a Bachelor of Education (Health and Physical Education) and a Master of Education (Policy Studies) and is currently completing doctoral studies at University of Sydney’s Sydney College of the Arts where his research and creative output is focussed on culturally modified trees. Terrence commenced at The University of Queensland in January 2022 in the role of Director of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit.