Country and Place

Country—always capitalised—and place is at the heart of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and communities. Our custodianship of Country spans tens of thousands of years and continues to this very day and into the future. The lands on which all UQ campuses reside always was and always will be Aboriginal Country.

As you navigate your UQ campus, you will see the influence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and cultures all around the University. For example, when the building of St Lucia campus commenced in March 1938, Aboriginal peoples’ relationship to this place was already being recognised. Aboriginal words were used to name the surrounding suburbs of Toowong (tuwong, a word believed to derive from the sound of the migratory Eastern Koel or the native White-Throated Nightjar) and Indooroopilly (nyindurupilli, meaning gully of leeches, or yindurupilly, meaning gully of running water) and the architect who designed St Lucia campus wished to embed Aboriginal motifs into the design of the Great Court.

This section of the UQ has a Blak History module will profile sites of significance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across UQ campuses.

The Great Court, St Lucia

Jack F. Hennessey was appointed the chief architect of St Lucia campus. There were many delays in constructing the buildings at St Lucia, including financial constraints and the focus on fighting and defence during the Second World War. However, building commenced in March 1938 and the final building for the new campus, the Biological Sciences (Goddard) Building, was opened in June 1962.

In Hennessey’s original designs of the campus, he mentions wanting to incorporate ‘Aboriginal ornament … to create an Australian tie from the earliest times up to today’ (East, 2014, p. 37). There was also supposed to be a Great Hall where the Michie building now stands. This hall was supposed to have Aboriginal rock art motifs decorating the ceiling. Unfortunately, this did not occur. Another ceiling, this time for a library reading room in the Duhig Building, was etched with Aboriginal motifs, but this ceiling has since been demolished.

Friezes and Murals Depicting Aboriginal People and Culture, St Lucia

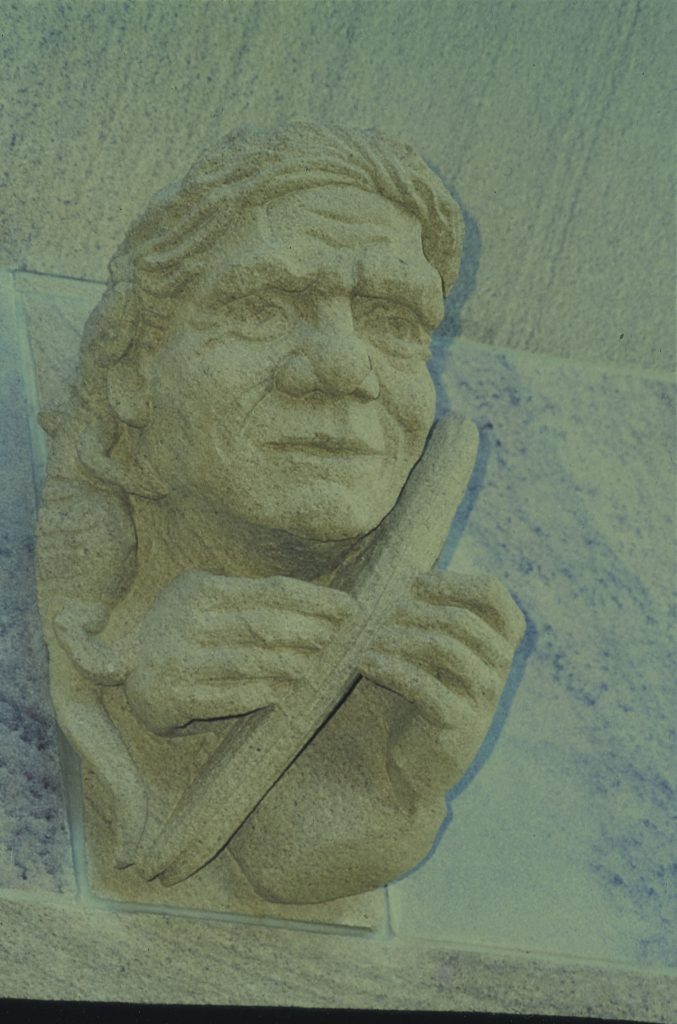

Hennessey’s influence carried over to John Theodore Muller, who was the first University Sculptor from the 1930s-50s. During this time, Muller formed a partnership with stonemason Frederick James McGowan and, together, they are credited with carving over 30 friezes into the Great Court that depicted his interpretations of traditional Aboriginal social life and culture (East, 2015).

You can still see these friezes on the outer entrances of the Forgan Smith Law and Arts buildings today and, while the friezes were created with admiration for Aboriginal culture and were based on drawing and carvings of Aboriginal people at the time, these representations evoke stereotypes of Aboriginal peoples as nomadic savages—a depiction that is now considered both harmful and offensive. These friezes should be considered with a critical eye and viewed in collaboration with representations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Within the Forgan Smith building where the Arts and Law faculties are housed is a mural by 1949 Archibald Prize-winning artist Arthur Murch (1902–1989), The arts of peace. Commissioned in 1951, the oil painting on wood-backed canvas depicts a Molonga corroboree. It has been speculated that the corroboree depicted was in response to a massacre of Aboriginal people by European settlers (East, 2014). When first commissioned, Murch was asked to depict one mural representing war and another representing peace. However, the University decided not to go ahead with the second mural depicting peace as it was seen as a repetition of the friezes in the Great Court (East, 2014).

Across the exterior wall of the Student Support Services building in the Student Union Complex is a large mural, painted by several Aboriginal artists under the direction of Joe Hurst, called White Australia has a black history. Once painted, the mural was immediately vandalised with a ‘KKK’ and Joe Hurst repainted over the letters and added an image of an AK-47 with a belt of bullets in the bottom right of the wall. If you walk past this mural today, you can still see the faint ‘KKK’ residue.

Mounted on the mural is a plaque from 26 May 2003 with the following statement from the late Sam Watson (1952–2019):

This is Aboriginal land

All people who walk upon this land

and who breathe in the air of this land

and who drink the water of this land

Must know and honour the law of the land.

This law says that all people are as one family.

This law says that there should be no hatred

or fear within our family.

Only when we love, respect and support each other

Can we know the truth of the land.

That is our word…

That is our land…

That is our law…

ONETIME!

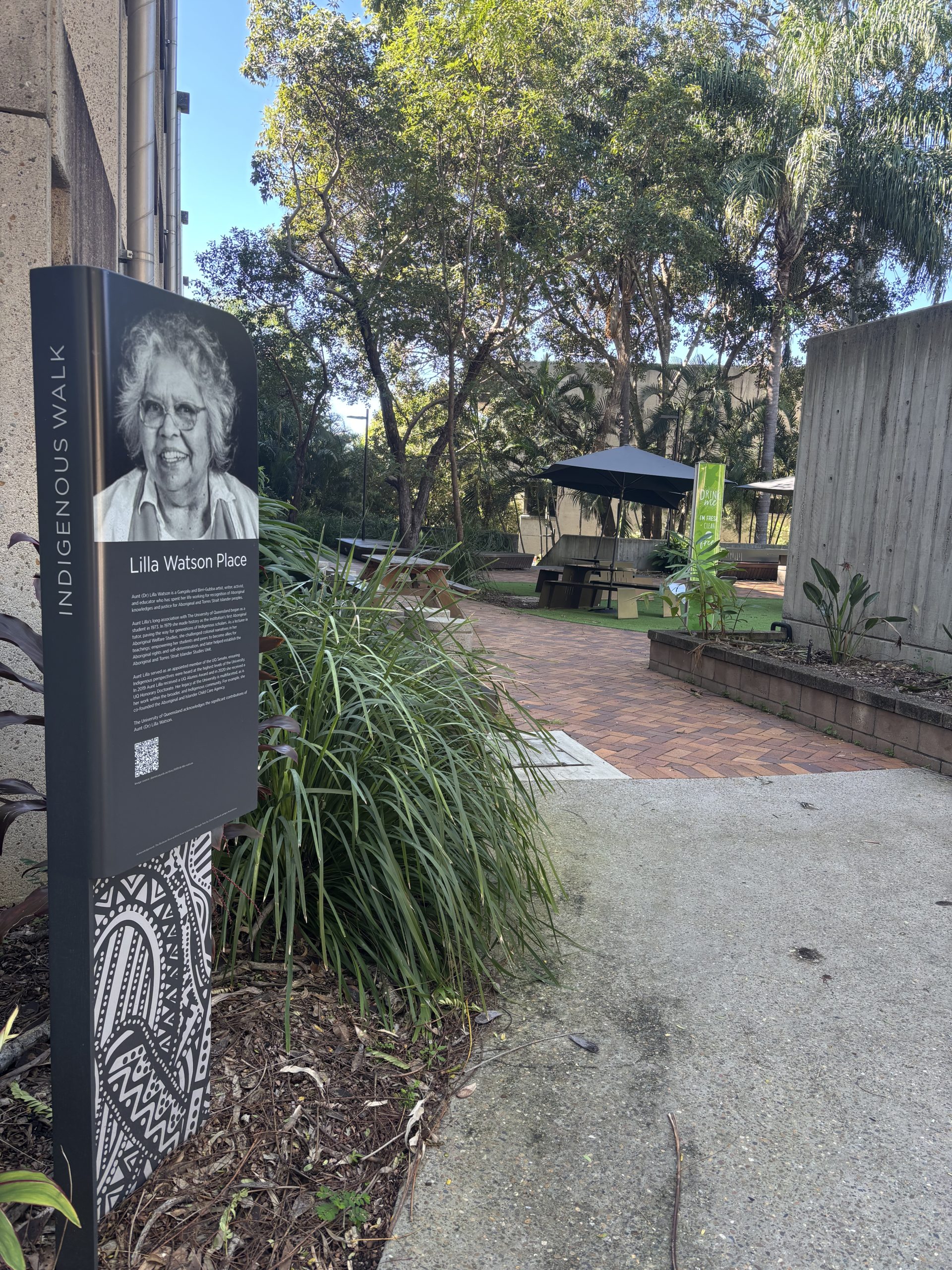

Lilla Watson Place, St Lucia

In October 2024, the UQ Forecourt was renamed ‘Lilla Watson Place’ to honour the first Aboriginal tutor employed by the university, Dr Lilla Watson. The renaming of this space not only recognises Dr Lilla Watson’s contributions to education and strong legacy as a respected Elder within the community, it also highlights UQ’s commitment to reconciliation through truth-telling and healing.

Further information about Dr Lilla Watson and her legacy at UQ can be found in the ‘Blak Education’ section of this module.

Sandstone Sculptures, St Lucia

Sandstone grotesques of Gaiarbau (Willie McKenzie), a Dungidau man from Jinibara peoples who made significant contributions to research in UQ’s Anthropology department from 1950-1959, and an unidentified Aboriginal woman were created by Rhyl Hinwood in the late 1970s and sit within the boundaries of the Great Court. The grotesque of Gaiarbau reflects his role in preserving the oral traditions of South-East Queensland and that the grotesque of the woman was carved beside him to add to this symbolism.

In her 2021 visual memoir, A sculptor’s vision – creating a legacy in stone, Hinwood admits that she was ignorant of any Aboriginal women who were connected to UQ, but has since learnt from her mistake. Upon further investigation of Fryer Library special collections material, it was discovered that Hinwood used a reference photo of an unnamed Aboriginal (possibly Arrente) woman while designing this grotesque. Two decades after designing these grotesques, Hinwood created the sandstone seat at Wordsmiths Writers Café under a paperbark tree. If you go and see this sculpture at the café, you will notice a tribute to one of Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s poems. To this day, Hinwood’s sandstone sculptures are considered great monuments to UQ’s history.

In addition to the grotesques of Gaiarbau and the unidentified Aboriginal woman, a grotesque of the late Dr Margaret Valadian (1936-2023) is set to be commissioned by Hinwood in the near future. Dr Valadian was the first known Indigenous graduate at UQ and was posthumously honoured with an Honorary Doctorate 2024. You can read more about Dr Valadian in the Blak Education section of this module.

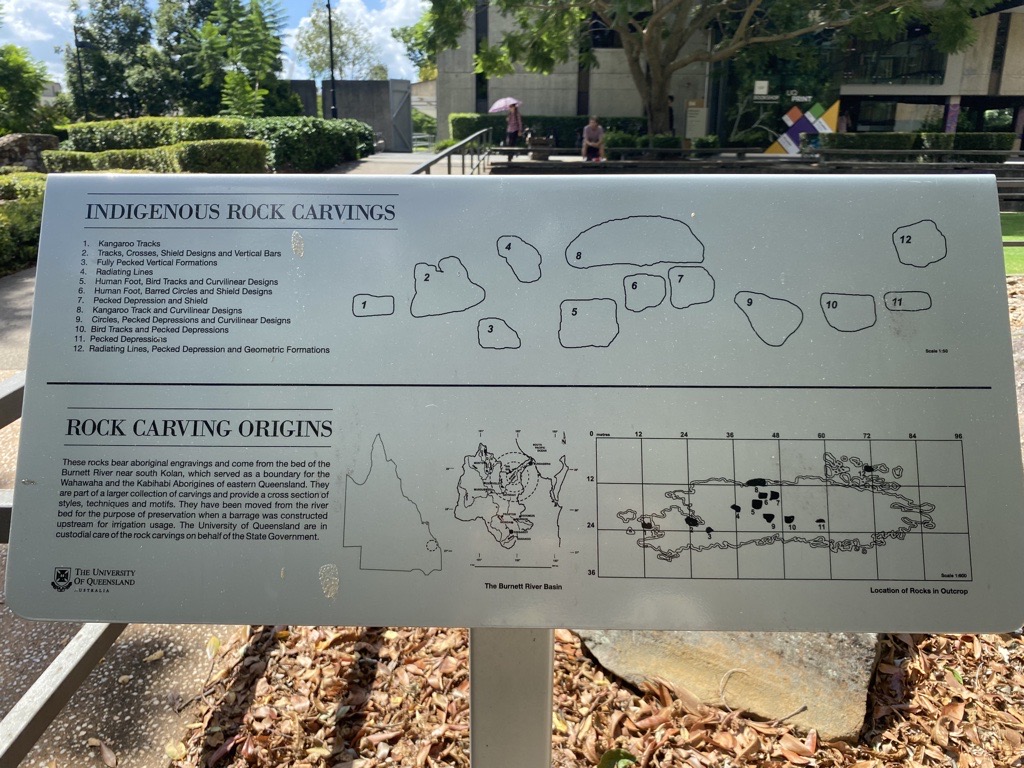

Indigenous Rock Carvings, St Lucia

An important sacred site of engraved rocks was removed from the banks of the Burnett River in Bundaberg during the first part of the 1970s because of an irrigation project (The University of Queensland, 2022). A number of Queensland institutions, including The University of Queensland, became custodians of the rocks.

These rocks were from an extensive Aboriginal art site from the Burnett River. The site was located on an isolated outcrop of sandstone on a sandy spit adjacent to the northern bank of the Burnett River, west of Bundaberg. More than 400 groups of engravings were identified in the soft sandstone.

Some of these rocks were distributed to UQ and installed in the Michie Forecourt at St Lucia.

Click for a text description of the Indigenous Rock Carvings sign

- Kangaroo Tracks

- Tracks, Crosses, Shield Designs and Vertical Bars

- Fully Pecked Vertical Formations

- Radiating Lines

- Human Foot, Bird Tracks and Curvilinear Designs

- Human Foot, Barred Circles and Shield Designs

- Pecked Depression and Shield

- Kangaroo Track and Curvilinear Designs

- Circles, Pecked Depressions and Curvilinear Designs

- Bird Tracks and Pecked Depressions

- Pecked Depressions

- Radiating Lines, Pecked Depression and Geometric Formations

Map of the rocks – numbered.

Rock Carving Origins

These rocks bear aboriginal engravings and come from the bed of the Burnett River near south Kolan, which served as a boundary for the Wahawaha and the Kabihabi Aborigines of eastern Queensland. They are part of a larger collection of carvings and provide a cross section of styles, techniques and motifs. They have been moved from the river bed for the purpose of preservation when a barrage was constructed upstream for irrigation usage. The University of Queensland are in custodial care of the rock carvings on behalf of the State Government.

Map of the Burnett River Basin.

Map of the location of the Rocks in the Outcrop.

UQ Reconciliation Garden and Log Circle, Herston

The UQ Reconciliation Garden is both an acknowledgment of the colonial history of Herston and a recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ connections to Country and place. The idea to create the garden came from traditional Yuggera custodian Gaja Kerry Charlton and Elder Carmel Schlege and staff from the UQ School of Public Health. Designed by Yuin landscape architect, Kaylie Salvatori, in consultation with the local Indigenous community, the garden prioritises plants that have medicinal and nutritional value within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures.

On the lawn to the south of the School of Public Health building is the Log Circle at Herston campus. Constructed in 1994, the Log Circle at Herston campus represents Herston campus as a place of storytelling, yarning, and activism (Marnane & Bower, 2021, p. 51).

Bush Tucker Garden, St Lucia

The UQ Bush Tucker Garden at St Lucia campus is home to a variety of native plant species that Indigenous people use for food, medicine, weapon creation, and technology building. Highlights in the garden include Davidson Plum, Gumbi Gumbi, Black Wattle, Lemon Myrtle, and Bunya Pine.

UQ Bush Tucker Garden Tour

In 2020, Alex Bond, an Aboriginal scholar, filmed a virtual tour of the Bush Tucker Garden. This tour and further information about the garden, its significance to local Aboriginal peoples, and plant information, visit the UQ Sustainability website.

UQ Bush Tucker Garden Tour with Alex Bond (13m 2s):

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit, Multiple Campuses

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit was established in 1984. Today, the Unit serves as a place for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, staff, researchers, and visiting community members to foster community, get support, and take refuge from an academic environment that can be harmful, distressing, and culturally unsafe.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit has dedicated spaces across multiple UQ campuses. At St Lucia campus, they are located in the Bookshop Building. At Gatton campus, they are located in the Morrison Hall.

The history of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit and its impact can be found in the Blak Education section of this module.

Video overview of this chapter – UQ has a Blak history – Country and Place (YouTube, 4m 46s):

References and Resources

Ackfun, S. (n.d.). In the eye of the Court. University of Queensland. https://shorthand.uq.edu.au/small-change/in-the-eye-of-the-court/

Contact Magazine. (2022). Indigenous Designs and Principles. University of Queensland. https://stories.uq.edu.au/contact-magazine/2022/indigenous-design-framework/index.html

Contact Magazine. (2021). UQ by design: marvellous murals. University of Queensland. https://stories.uq.edu.au/contact-magazine/2021/uq-by-design-marvellous-murals/index.html

East, J. W. (2014). No Mean Plans: Designing the Great Court at the University of Queensland. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:337565

East, J. W. (2015). John Theodore Muller (1873-1953) Master Stone Carver to the University Of Queensland: A Biographical Sketch. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:349349

Fredericks, B. (2020). ‘Collaborative Creative Processes That Challenge Us as “Anomaly”, and Affirm Our Indigeneity and Enact Our Sovereignty’. M/C Journal 23(5). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.1674

Fryer Library Manuscripts. UQFL458 University of Queensland History Collection. https://manuscripts.library.uq.edu.au/index.php/uqfl458

Kerkhove, R. (n.d.). Indigenous Aboriginal Sites Of Southside Brisbane. Mapping Brisbane History. https://mappingbrisbanehistory.com.au/brisbane-history-essays/brisbane-southside-history/first-australians-and-original-landscape/indigenous-sites/

Marnane, K. and Bower, T. (2021). Campuses on Countries: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Design Framework Engagement Report at The University of Queensland. St Lucia, QLD Australia: The University of Queensland. https://doi.org/10.14264/c684e38

Master Builders’ Federation of Australia & Illuminating Engineering Society of Australia. (1951). Queensland University Story of its Conception and Design: Magnificent £2,000,000 Project. Building and engineering. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-300933473/

O’Leary, Kirsten. (n.d.). A place to reflect: Aunt Lilla Watson celebrated at UQ. Contact. https://stories.uq.edu.au/a-place-to-reflect-aunt-lilla-watson-celebrated-at-uq/index.html

School of Public Health. (2022). Indigenous heritage and flora flourishing in UQ Reconciliation Garden. University of Queensland. https://public-health.uq.edu.au/article/2022/06/indigenous-heritage-and-flora-flourishing-uq-reconciliation-garden

Sustainability. (n.d.). Bush Tucker Garden. University of Queensland. https://sustainability.uq.edu.au/projects/sustainable-food/bush-tucker-garden

The Courier-Mail. New university to Open in 1939. (1936). https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/36997555/1967435

The Old Museum. (2018). Traditional story of the land- Barrambin (York’s Hollow). https://www.oldmuseum.org/post/traditionalstory

University of Queensland. (n.d.). Great Court Carvings. https://campuses.uq.edu.au/files/10170/Great-court-carvings-map.pdf

UQ News. (2024, 10 July). Great Court carving announced as UQ confers honours. https://www.uq.edu.au/news/article/2024/07/great-court-carving-announced-uq-confers-honours