7. Fake news, facts and data

Fake news

Fake news was declared Macquarie Dictionary’s Word of the Decade in 2021. Fake news is false information which is manipulated to confuse or fool people.

In 2018, UQ was the subject of fake news when it was reported that UQ had banned the use of the terms mankind and workmanship. On April 1 every year, also known as April Fool’s Day, many normally reliable newspapers and news websites publish fake news to fool people.

Try the ABC RN’s “The great social media misinformation quiz” quiz on spotting fake news.

Fake news is often spread through social media. It can be used to generate profit, as people click on links to find out more, or to further a particular agenda.

Fake news and artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) has made creating content easier than ever which has led to a rise in fake news in both text and video format. Those who want to spread false information now have tools to create and spread it quicker than ever before.

Groups like NewsGuard monitor the spread of AI-generated misinformation. But there’s another problem: the massive spread of low-quality AI content, often called “AI slop.” Unlike fake news, AI slop isn’t designed to be false or misleading (but frequently is due to lack of human oversight). It’s usually made with very little effort and value to maximise clicks and engagement.

Experts worry that too much AI slop could harm the quality of information on the internet.

Bots

Bots are fake social media accounts generated by an automated service. The article – Meet ‘Sara’, ‘Sharon’ and ‘Mel’: Why people spreading coronavirus anxiety on Twitter might actually be bots – explains the potential danger of bots, discusses why it is done and lists indicators you can look out for, including:

- recently created accounts

- no followers

- no last names and alphanumeric handlers

- only a few posts.

Deepfakes and AI generated videos

Deepfakes use machine-learning algorithms to create fake audio and video of real people. The technology is so sophisticated that it makes it very hard to know that it is fake. It is important that you evaluate the reliability of content that you see on social media because even when it looks real it might not be.

![]() Watch this video – Fake News – and how to spot it (BBC video, 2m59s)

Watch this video – Fake News – and how to spot it (BBC video, 2m59s)

Text-to-video artificial intelligence tools such as Sora and Veo have created further concerns around fake audio and visual content. The ability for anyone to generate a realistic video with only a text description has enabled further spread of convincing misinformation online. Videos mimicking real news reports are already being spread on social media platforms making it difficult to tell real reports from fake ones.

![]() Watch this video – AI news videos blur line between real and fake reports (NBC News, 7m4s).

Watch this video – AI news videos blur line between real and fake reports (NBC News, 7m4s).

News and satire

Writers or broadcasters sometimes use satire, including irony and dry wit, to parody or criticise public figures or to comment on current events. It is important to note that while satirical websites also create fake news items, the purpose is usually to entertain, rather than to mislead or manipulate. There are satirical news websites such as:

How to spot fake news

The Conversation reported that many young Australians are unable to identify fake news online.

If you are reading news items and are planning to use them in your assignments or social media, check the website where the ‘news’ is reported before you do. This BBC video on how to spot a hoax gives viewers tips on how to recognise fake news.

![]() Ask yourself the following questions:

Ask yourself the following questions:

- Has this story been reported by a reputable source such as the ABC, BBC, or The Guardian?

- Does the headline fairly reflect the contents of the news story, or is the headline purposefully sensational in order to get clicks (i.e. clickbait)?

- Who authored the news story? Are they credible?

- Is it a joke story? It may be satire reported as a true story.

- Have you checked a fact-checking website such as Snopes or Full Fact?

For more information, read evaluating the information you find.

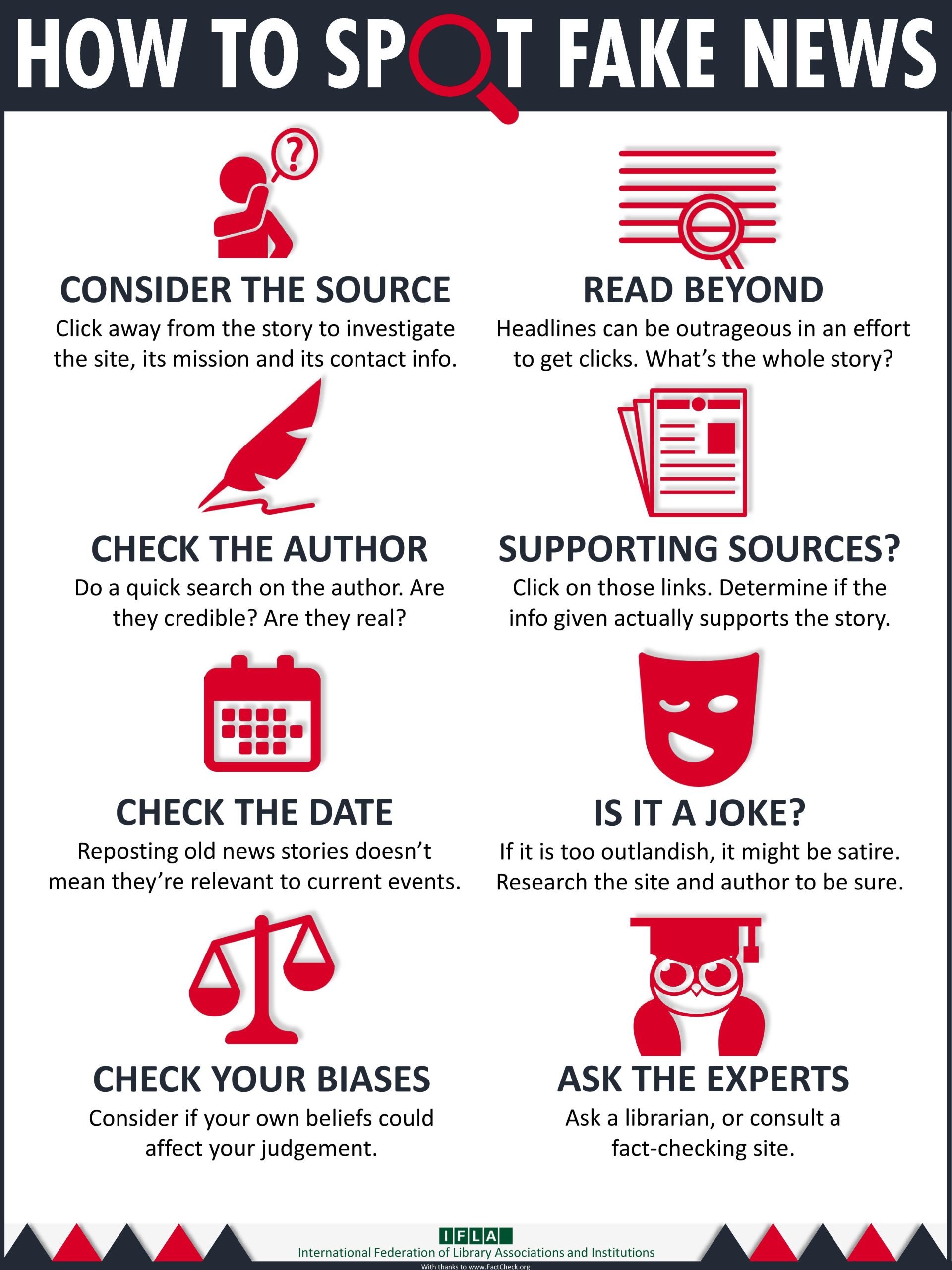

![]() This infographic, produced by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, outlines steps you can take to check if news is fake or not.

This infographic, produced by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, outlines steps you can take to check if news is fake or not.

Artificial intelligence has complicated these issues around identifying what is fake news and information. Read “Algorithms are pushing AI-generated falsehoods at an alarming rate. How do we stop this?” to learn more.

Misleading data

‘There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.’ – attributed to Benjamin Disraeli by Mark Twain in Chapters from my Autobiography

Data and statistics are often used in news articles, debates, and scholarly articles with varying degrees of accuracy. Statistics are often used to persuade an audience of a fact. However, it is easy for statistics to be misleading, and this can be intentional or unintentional.

![]() Watch How statistics can be misleading (YouTube, 4m18s)

Watch How statistics can be misleading (YouTube, 4m18s)

Fact Check, an initiative of ABC News and RMIT University, has great analyses of the uses of statistics in the media, and is a great place to look for examples.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics has a guide to writing about statistics which is aimed at people writing policy, but is still applicable to your assignments.

For more information about how you can use data in your assignments, see our Work with data and files module.