2 Evidence-based practice

- Evidence-based practice overview

- What is evidence-based practice?

- Clinical expertise

- Best research evidence

- Patient values

- Online resources about evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice overview

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is used across health disciplines. It also extends beyond health into areas such as education.

The use of evidence-based practice (EBP) ensures clinical practice is based on sound evidence and patients benefit as a result.

An EBP approach allows health professionals to find and critically evaluate evidence in order to provide patients with the best treatment.

How evidence can be distorted

Ben Goldacre: Battling bad science (Ted Talk, 14m4s) explains the ways evidence can be distorted, from the blindingly obvious nutrition claims to the very subtle tricks of the pharmaceutical industry.

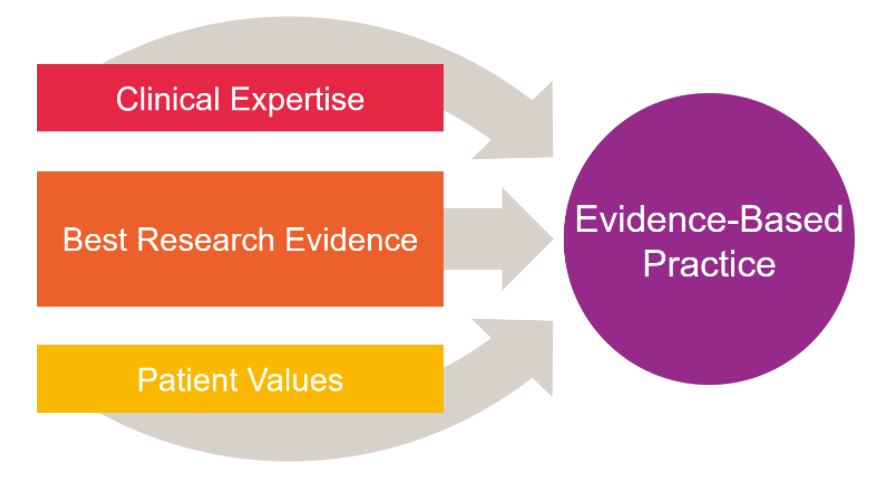

What is evidence-based practice?

In 1996, Professor David Sackett and his colleagues explained that evidence-based medicine “integrates the best external evidence with individual clinical expertise and patients’ choice”. Read the full article Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t (PDF, 544KB).

![]() What is the difference between EBM (Evidence-Based Medicine) and EBP (Evidence-Based Practice)?

What is the difference between EBM (Evidence-Based Medicine) and EBP (Evidence-Based Practice)?

The term EBM is used interchangeably with evidence-based practice or evidence-based health care.

Source: BMJ Best Practice Learn EBM.

Adopting evidence-based practice in health and medical disciplines, involves a combination of three elements:

- clinical expertise

- best research evidence

- patient values.

Clinical expertise

Sackett defined individual clinical expertise as:

“…the proficiency and judgment that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice and it is this expertise that decides whether the external evidence applies to the individual patient at all and, if so, how it should be integrated into a clinical decision.”

Source: Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. (PDF, 544KB)

EBM is not dogmatic, “cookbook ” medicine. Instead, it relies on the expertise of a conscientious clinician in partnership with the patient. The clinician must navigate a sea of information and decide how best to apply it to the individual patient.

EBM is not dogmatic, “cookbook ” medicine. Instead, it relies on the expertise of a conscientious clinician in partnership with the patient. The clinician must navigate a sea of information and decide how best to apply it to the individual patient.

Source: Evidence-based medicine: Common misconceptions, barriers, and practical solutions.

“The reason that minor infections don’t usually kill us, that people can live with cancer and that we know that smoking is harmful” is because an evidence-based approach has been adopted. Research evidence has been integrated into clinical practice and led to better outcomes for patients.

Read Evidence-based medicine matters: Examples of where EBM has benefitted patients for more stories.

Read these articles to learn more about the role of clinical expertise in evidence-based practice:

- Expertise in evidence-based medicine: a tale of three models

- Reconciling evidence and experience in the context of evidence-based practice

Best research evidence

Using the best research evidence is important. However, sometimes the current evidence is inconclusive, or of a low quality.

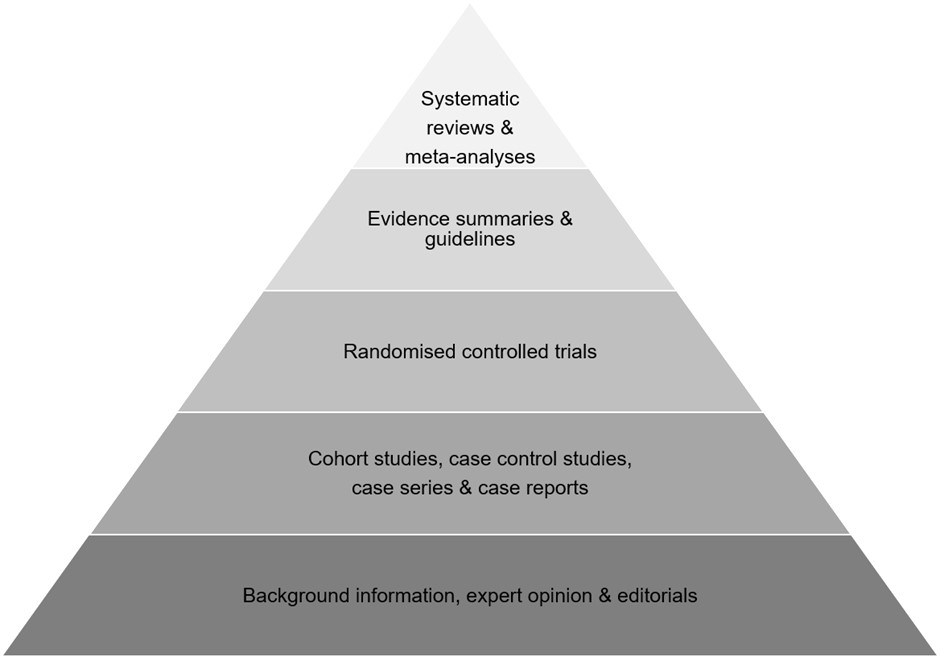

Types and levels of evidence

To inform your clinical practice, it’s best to look for the highest level of evidence available. A pyramid is often used to represent the hierarchy of evidence, with the higher quality evidence at the top.

Best evidence includes empirical evidence from randomized controlled trials; evidence from other scientific methods such as descriptive and qualitative research; as well as use of information from case reports, scientific principles, and expert opinion.

Source: Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Chapter 7.

For example, the following evidence pyramid provides a hierarchy of research and study types:

The levels of evidence (highest to lowest) are:

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- Evidence summaries and guidelines

- Randomised controlled trials

- Cohort studies, case control studies, case series and case reports

- Background information, expert opinions and editorials.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Systematic reviews aim to identify, evaluate and summarise the findings of all relevant individual studies, thereby making the available evidence more accessible to decision-makers. When appropriate, combining the results of several studies gives a more reliable and precise estimate of an intervention’s effectiveness than one study alone.

Source: Systematic Reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care.

Dr Benjamin Spock’s advice on babies’ sleeping position was disproved according to the evidence from studies and a systematic review. A systematic review published in 2005 concluded that:

Advice to put infants to sleep on the front for nearly a half century was contrary to evidence available from 1970 that this was likely to be harmful. Systematic review of preventable risk factors for SIDS from 1970 would have led to earlier recognition of the risks of sleeping on the front and might have prevented over 10 000 infant deaths in the UK and at least 50 000 in Europe, the USA, and Australasia.

Source: Infant sleeping position and the sudden infant death syndrome.

Meta-analysis involves the statistical analysis of results from the individual studies included in a systematic review. The article What is meta-analysis? provides an overview of this research process and recognises that “the strength of conclusions from meta-analysis largely depends on the quality of the data available for synthesis. This reflects the quality of individual studies and the systematic review” (Shorten and Shorten, 2013).

Guidelines

Clinical guidelines are designed to support the decision-making process in patient care based on systematic reviews of clinical evidence, the main source for evidence-based care.

Clinical guidelines and trials guide – Find clinical guidelines and trials in the health sciences.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are particularly important for determining the effectiveness of interventions or therapies. The article Explaining the importance of clinical trials describes the use of randomised controlled trials.

The use of the drug thalidomide, a sleeping pill also utilised to relieve morning sickness, is an example of why it’s important to test new treatments.

James Lind’s prospective controlled trial for the treatment of scurvy in 1747 provides one of the earliest accounts of a clinical trial.

Other study types

It is not always feasible or ethical to conduct a clinical trial. Other study types can be used when ethical considerations are a factor, such as a cohort study. This was research method was first adopted by Doll and Hill in what’s known as the British Doctors Study.

Smoking had always been seen as a benign activity until researchers began to question this proposition in light of observations of smokers. In the UK, Richard Doll and Bradford Hill performed a case-controlled study in 1950 called Smoking and carcinoma of the lung: preliminary report. This was followed by the British Doctors Study, a cohort study which tracked UK doctors for 50 years. This research proved the link between smoking and cancer.

Smoking had always been seen as a benign activity until researchers began to question this proposition in light of observations of smokers. In the UK, Richard Doll and Bradford Hill performed a case-controlled study in 1950 called Smoking and carcinoma of the lung: preliminary report. This was followed by the British Doctors Study, a cohort study which tracked UK doctors for 50 years. This research proved the link between smoking and cancer.

Best evidence for different types of clinical questions

When searching for evidence, the type of clinical question helps determine the study type to look for. The table below provides a guide to finding the best evidence for your clinical question.

| Type of clinical question | Study types |

|---|---|

| Therapy/Treatment (Effectiveness of interventions) |

Randomised controlled trial (RCT)

Example: |

| Prevention (Effectiveness of preventive measures) |

RCT, Cohort, Case control, Case series

Examples: |

| Diagnosis (Validity and reliability of diagnostic test for identifying disease) |

Prospective, blind controlled trial comparison to gold standard

Example: |

| Prognosis (Likely course or outcome of disease) |

Cohort, Case control, Case series

Examples:

|

| Aetiology/Harm (Cause of disease) |

RCT, Cohort, Case control, Case series

Example: Five-year follow-up of harms and benefits of behavioral infant sleep intervention: randomized trial |

| Meaning (Patient experience) |

Qualitative study

Read the article Choosing a qualitative research approach |

| Cost analysis (Comparing costs and health outcomes of interventions) |

Economic analysis

Example: Cost-analysis of opportunistic influenza vaccination in general medical inpatients |

For all types of clinical questions, a systematic review or meta-analysis may provide the best evidence.

Examples:

- The association between the Mediterranean dietary pattern and cognitive health: A systematic review

- The risk of COVID-19 related hospitalisation, intensive care unit admission and mortality in people with underlying asthma or COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Exercises

Read the introduction to the 2011 Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine’s levels of evidence to answer this question:

Critical appraisal is important

It’s essential to evaluate the quality of evidence. There are a number of critical appraisal tools or checklists for this, including the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists.

Critical appraisal

These Critical appraisal videos (YouTube 21m14s) examine 10 principles that can be applied when critically appraising literature.

Bias

An understanding of the role of bias in research is also fundamental in determining the quality of evidence. Smith and Noble state that:

Understanding research bias is important for several reasons: first, bias exists in all research, across research designs and is difficult to eliminate; second, bias can occur at each stage of the research process; third, bias impacts on the validity and reliability of study findings and misinterpretation of data can have important consequences for practice.

Source: Bias in research.

There are many biases that can affect health research, as mapped in the Catalogue of bias.

Health research – Learn about advanced health research techniques.

Patient values

It’s important to consider patient preferences and values in evidence-based practice.

Patient preferences can be religious or spiritual values, social and cultural values, thoughts about what constitutes quality of life, personal priorities, and beliefs about health. Even though healthcare providers know and understand that they should seek patient input into decisions about patient care, this does not always happen because of barriers such as time constraints, literacy, previous knowledge, and gender, race, and sociocultural influences.

Source: Integrate evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences and values.

Shared-decision making and health literacy are important aspects to consider in incorporating patient values into evidence-based practice.

Patients may have preferences when it comes to defining the problem, identifying the range of management options, selecting the outcomes used to compare these options, and ranking these outcomes by importance.

![]() Further reading:

Further reading:

Bringing shared decision making and evidence-based practice together.

Health literacy – Learn about healthy literacy and its importance.

Learn more about how to adopt an evidence-based approach by exploring online resources.

Cochrane Evidence Essentials – A free online resource offering an introduction to health evidence, and how to use it to make informed health choices.

University of Oxford, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) – EBM guides and practical how to’s for researchers, clinicians, students and teachers.

Evidence based healthcare

Viva La Evidence (YouTube 4m18s) — a parody of Coldplay’s Viva La Vida – a song all about evidence based healthcare.