Conclusion

The concept of the public interest has been incorporated into or examined by many, many disciplines and fields – from accountancy to anthropology, journalism to psychology (Johnston, 2017). Public interest is integrated into law, governance, and public policy across democratic systems of government on a global scale. Central to how it is understood and applied, is how it is communicated. This book has brought together a series of theories, concepts and practices that are pieced together to explain and illustrate this – that is, Public Interest Communication in theory and action.

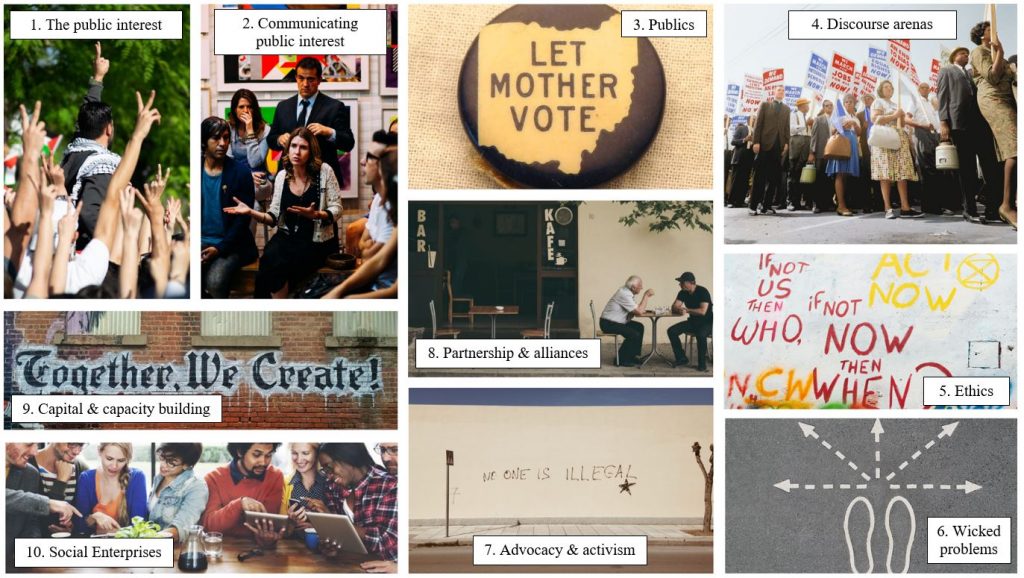

Public Interest Communication: a thumbnail of the book

In building Public Interest Theory in Part 1 we introduced the concept of ‘the public interest’, exploring how scholars have debunked any idea that there is one, single, over-abiding public interest; rather, how many interests compete within the value systems and lived existences of the many individuals and publics that make up society. Fragmented and heterogeneous, publics are often brought together by a particular issue – these publics are diverse and changeable reflecting the dynamic nature of society.

Their interests are usually made public – or communicated publicly – in public exchange sites called ‘discourse’ or ‘public arenas’. These arenas, which are acted out live in, for example, protests and meetings, or mediated via social media and television, provide forums or so-called “public interest battlegrounds” (Heath & Waymer, 2018, p. 40), enabling discussion and debate to occur. In the very best of public interest communication, these assume that dialogue, and with that, actively listening to others, take place. In reality, not everyone can access these forums for debate and not all interests will be heard or made public. The democratic ideal, however, is assumed for public interest communication to occur. Our final podcast on Veronica Koman — in the text box on the right — demonstrates what can happen when arenas for public interest debate are curtailed.

Podcast. Veronica Koman: The Saviour Angel of the Papuan People

What happens when people speak out about issues in places where public interest communication can be challenging? In this podcast Lorita Vina tells the story of Veronica Koman, an Indonesian human rights activist and lawyer who has spoken up on human rights issues in Papua and West Papua provinces. Her efforts have both achieved accolades and threats: from winning the Sir Ronald Wilson Human Rights Award in 2019 to receiving online threats and disinformation campaigns.

Key to this theoretical underpinning which includes publics, dialogue, listening, and spaces in which this can occur, is reflexive practice or having the capacity and will to challenge existing thinking and work within an ethical framework. It is therefore important to understand how public interests and professional codes of ethics intersect. In this book, however, we focus more on individual behaviours than those of the professions, highlighting so-called virtue-ethics, which calls for developing ‘good’ communication habits which are put into practice everyday.

Part 2 turns to public interest communication in action, identifying contexts where ‘interest-forming practices’ (Johnston & Pieczka, 2018) occur and ways in which these practices are acted out at local, national and international levels. These five chapters bring their own theories to the book and to scholarship more broadly, but they are also used here to illustrate what public policy scholar Barry Bozeman calls ‘public interest in action’ (2007) and we call ‘public interest communication in action’. The first of these sites of action are ‘wicked problems’ – problems that are the most complex and difficult to solve and, indeed, cannot be fully (re)solved. Here, we identify the United Nations 17 Sustainability Goals – ranging from poverty and hunger to climate action and peace – these are among the most wicked of the world’s problems in our time. Social movements see some wicked problems, over time, find positive social and political change brought about through advocacy, activism and protest. For example, social movements against racism, slavery, discrimination, which see fairer societies result.

Public interest communication is also seen in action through partnerships and alliances which form to enable the sharing of resources, mutual support, achieving certain outcomes. These take the form of different groups, individuals or organisations working together through, for example, sponsorships between a corporate and a sporting group or individual. When groups of like-minded people are brought together, we see publics emerge and become active. This is also the ground in which social capital and capacity building emerges, where governments, corporates, and civil society work collaboratively to achieve outcomes for communities, driven by the needs of communities. Finally, the book explores that hybrid model of the social enterprise which combines causes with business thinking to help society and the environment. Inherent in these enterprises is a ‘giving back’ approach, explained in two popular theories of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and enlightened self interest.

There are other ways we might understand public interest in theory or action, such as through philanthropy, pro bono service, or volunteerism, which take the idea of public interest communication into other spaces. The idea of this book is open up the possibilities of how communication in the public interest can take many forms. Central to it are the six pillars we outlined at the start of the book: publicness, accessibility, substantive anchoring, rationality, inter-subjectivity and connectedness which combine to provide the building blocks for public-interest forming practices (Johnston & Pieczka, 2018). These do not come easily. As Communication scholar John Durham Peters points out, communication can be “a risky adventure” (1999, p. 267) without any guarantees; a “political problem of access and opportunity” (p. 56).

Using communication to work through difference

As we wrap up the book, we return to Dewey’s insightful comment from chapter 1:

‘Of course, there are conflicting interests; otherwise, there would be no social problems’. (Dewey, 1991, p. 81).

Provocative and confronting, this challenging statement reminds us that society is complex and cannot be ‘managed’ in any simple way. His remarks, written almost a century ago (written in 1935 but published in 1991), called for “organized effort” to try to resolve issues and problems in what he called “the confusion, uncertainty and conflict that mark the modern world” (p. 92). His ‘modern world’ – at that time between the Great Depression and World War Two – was at a different time to ours, but our challenges are no less daunting. As humankind navigates global challenges and crises – the coronavirus pandemic, global warming, and geopolitical tensions – Dewey’s description of threats to our world continue to resonate.

Yet, as huge as these issues were for him, and are now for us, he had confidence in humankind. Central to this was human’s capacity to communicate in effective and productive ways, with different publics, actively listening to what others are saying even when they disagree, and to inquire, find evidence and discovery in seeking to manage and resolve public interest clashes.

Let’s look at an example from within the context of COVID-19. One issue which emerged during the pandemic has been the division between those who are vaccinated and those who are not. As this podcast explains, a problem is that the so-called ‘anti-vaxxers’ are being marginalised and demonised by far more dominant narratives from governments and health professionals. The clear distinction between those who ‘are’ and those who ‘are not’ is simple for those who are not faced with the opposing point of view. However, for families, friends and colleagues who do not share the perspectives of those around them, this has been a divisive time. Listen to the podcast from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) on ‘How do I talk to people who don’t want to be vaccinated?’ to hear a moderate approach to this problem. It provides some tips and workable solutions for dealing with what has emerged as a ‘wicked problem’.

In looking towards the future, this short video of young people speaking at the Davos World Economic Forum shows how public interest communication is taking place in the public sphere, what motivates people to engage in it and how it can take many forms. From disability rights, to climate change action, to increased equality, communication about the public interest is taking place every day, led by individuals stepping up to join public debate and advocate for their cause.

Public interest communication for humanity

Following Dewey’s earlier statement, he went on: “The problem under discussion is precisely how conflicting claims are to be settled in the interest of the widest possible contribution to the interests of all – or at least of the great majority” (1991, p. 81). Remember again the timing – he was deeply committed to working together for the future of democracy. Other scholars since then (see Habermas, 1986, 1996; Fraser, 1990; Sorauf, 1957) have taken these ideas and advocated for democracies by focussing on those who are not part of the majority – these are minority publics, under-represented or marginalised people who also need to be considered in public interest thinking and decision-making. In this book we have endeavoured to shine a light on these individuals, groups and causes in order to truly understand what public interest communication is about. If we return to another concept from our first chapter, this takes courage – the challenge is therefore to be courageous individuals who use the power that communication brings to work for the best possible outcomes by putting this thinking into action.

An environment in which individuals discuss, deliberate, exchange opinions and form public opinion.