7 Advocacy and activism

Social movements have played a critical role in challenging dictators, advancing democracy, gaining rights and addressing environmental issues in communities around the globe. Many of us celebrate and enjoy the benefits achieved through the efforts of past social movement participants before us: Women around the world have engaged in hunger strikes, demonstrations, and community canvassing to secure the same rights as their male counterparts, with a century of achievements accrued in response. In more recent decades social movements have won LGBTIQA+ and disability rights, democratic freedoms and elevated demands for the rights of nature. Social movements have changed the world many times over. Which of the following have you heard of? Can you put them in the order in which they happened?

You may have noticed that it can be difficult to decide when social movements start and end. This is because often movements may emerge many years after people begin to engage in advocacy.

Advocacy is the core activity of all social movements: the “act of persuading or arguing in support of a specific cause, policy, idea or set of values” (Cox & Pezzullo, 2016, p.177). Advocacy, like all forms of public interest communication, takes place in complex, dynamic discourse arenas. These arenas include the social environments and physical settings where advocates’ interactions with other individuals and groups generate particular decisions or outcomes (Jasper, 2019). It is when individuals come together and advocate for change on a particular shared cause, that a social movement is formed. Other components of these social movements include campaigns, tactics and outcomes.

But what is the difference between advocacy and activism? Advocacy becomes activism when it takes a specific form within a discourse arena.

‘Activism is defined as the use of direct and noticeable action to achieve a result, usually a political or social one’ (Cambridge Dictionary).

In practice these definitions are often used differently in different nations and contexts. This is because social movements are inherently extremely complicated systems, composed of a multitude of actions undertaken by a multitude of actors, operating within disparate groups and factions, all with potentially different motivations and goals (Louis et al., 2020). It is both the gift of public interest communication that individuals can become advocates for a cause close to their heart, and the challenge to public interest communicators to ensure that their messages are heard and respected. In the following Q&A video Jane and Robyn talk about the distinction between activism and advocacy and how it fits into the broader concept of public interest communication.

Interview on activism and advocacy and how these align with public interest communication

Activism categories

Activism can take different forms in different countries, and can lead to different responses in different countries. In pluralist societies with open political systems, publics are provided avenues to voice dissent and advocate for their cause. In these societies activism can include activities such as joining political parties, writing submissions, marching in rallies, signing petitions and forming new public interest groups. These activities may not be possible in other societies. For example, while our analysis of public interest communication in this book focuses primarily on pluralistic, democratic societies, activists in other societies around the world experience violence and suppression at frightening rates (Global Witness, 2019). In many countries ‘activism’ may not be possible, and may, in fact, be heavily suppressed.

Given this complexity, forms of activism are loosely grouped into two overarching categories: conventional actions (also called ‘normative’, or ‘institutional’) and radical actions (also called ‘non-normative’, ‘extra-institutional’, or ‘civil resistance’ in its non-violent form, Moskalenko & McCauley, 2009).

- Conventional actions

- activities which use legal, or institutional channels to promote the cause. For example, in Australia it is legal to hold rallies, organise petitions and vote in local, state and federal elections. Engaging in these sorts of activities could be considered conventional activism.

- Radical actions

- actions which operate outside conventional, legal, or institutions channels of change. In many countries it is illegal to form a blockade, to barricade a motorway or occupy government buildings, therefore these would be classified as radical actions.

However, such a simple division between conventional and radical activism is easier said than done. Some actions which are conventional in one context will be radical in another. Consider the following quiz: how you would categorise these types of activism if they took place in your country?

Activism and advocacy involves more than just holding rallies and petitions. There are many other things activists must do to advance their cause, which include:

- Design campaigns

- Implement actions to persuade others of the justness of their cause

- Motivate supporters to join their cause

- Seek support from third parties such as the media and other interest groups

- Suppress/avoid counter-mobilisation

- Avoid radicalisation and factionalism within their own ranks

Activists also have to create groups in order to organise and undertake their actions. These groups can be highly diverse organisational structures ranging from informal teams of friends, loosely structured ‘grass roots’ organisations, or large NGOs or formal networks. Many of these groups may have many resources such as money and access; most, however, will have little of either and have a heavy dependency on volunteer labour and skill (Gulliver et al., 2020). Furthermore, much of what is reported in the media and that we hear about on a day to day basis are radical actions, as they are newsworthy and can generate significant debate and discussion across multiple discourse arenas.

What do you think is the most common type of activism that actually takes place? In 2018 Robyn did an analysis of the Australian environmental movement to ask this exact question. Scroll through the following slides to find out what she found.

Advocacy ‘works’ when advocates are able to persuade others that their cause is just. It is not about competition; but instead about the ability of different public interest groups to engage the goals and interests of other players in the arena (Jasper & Duyvendak, 2015). There is a rich body of research around the particular dynamics of social movements and how they take advantage of opportunities within arenas (such as ‘political opportunity theory’ and ‘resource mobilisation theory’). There are some opportunities which have been shown to be particularly important: The existence of political allies, supportive public opinion and favourable media coverage all represent opportunities which can determine the effectiveness of protest in achieving its goals (Agnone, 2007; Johnson, Agnone, & McCarthy, 2010). These characteristics reflect particular arenas and other groups that advocates must engage with, as well as some of the challenges they face in each.

The policy arena

Many activist campaigns seek to elicit policy change and/or target political entities (Gulliver, Fielding, & Louis, 2019). Groups active in this arena include policy makers and government departments, as well as lobby groups, think tanks and corporations (Dobbin & Jung, 2015). The challenge for many advocacy groups is gaining access to this arena; even in the case of mass public support for a cause, such as opposition to involvement in the 2003-2011 Iraq war, for example, it can be difficult to achieve political influence.

The media arena

Favourable media coverage is important for building public support and mobilising other people to join the advocates cause. Traditional and social media channels can help shape public opinion, which has been shown to then influence politician’s responses to the cause (Burstein, 2003). Groups operating within the media arena can include media conglomerates, broadcasters and publishers, as well as intellectuals and experts. A challenge for advocates in this arena is maintaining media interest, which can require a constant reinvention of new protest types, each of which need to be more radical, disruptive and attention grabbing than the last (Andrews & Caren, 2010; Lester & Hutchins, 2012)

The advocacy network arena

Other advocacy groups offer an important source of support, whether financial, emotional or practical. Gaining support from other advocacy groups enable strong and sustainable coalitions, which can increase advocates ability to gain power and achieve their goals (Tarrow & Tilly, 2007). Groups within the advocacy network arena can include NGOs, other grassroots groups focusing on similar causes, identity groups such as religious or ethnic groups, or trans-national advocacy organisations and coalitions. This arena can be a positive source of support for groups as well as an ongoing challenge; the formation and dissolution of like-minded coalitions is a constant feature of social movement dynamics.

What does advocacy and activism achieve?

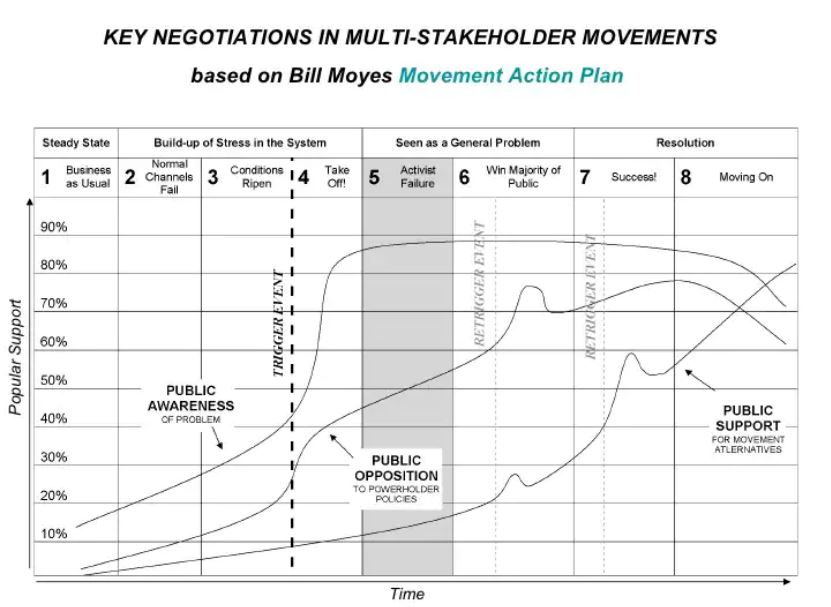

Why do some movements grow, build power and achieve their goals, while others shrink and eventually dissipate? There is a large body of literature crossing a multiplicity of research fields looking into the factors that influence social movement mobilization and the achievement of movement goals. Bill Moyer’s Movement Action Plan (1987) described eight stages of a social movement, and was designed to help activists chose the most effective tactics and strategies to match their movement’s stage. The following image matches the eight stages with public awareness, public opposition and public support.

Despite our understanding of how movements may grow and change over time it remains difficult to measure whether advocacy is actually successful. Like all public interest communication, advocacy is a dynamic process of listening and responding to other’s interests. This process can seek to achieve quite intangible results, such as gaining greater sympathy for their cause, or motivating volunteers to participate more frequently in activist activities.

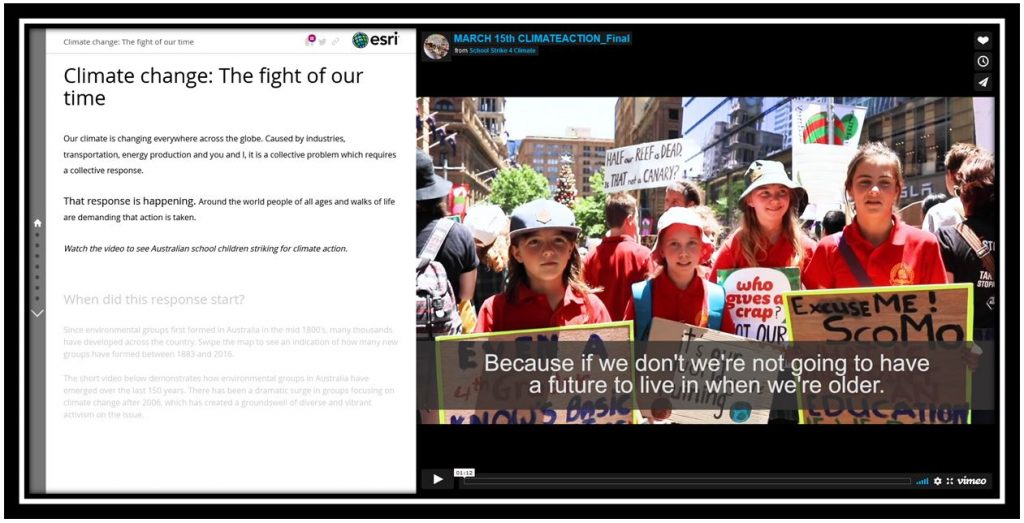

However, there is one way to measure outcomes: by analysing the specific goals of selected campaigns and tracking whether these goals are achieved. This work has been undertaken by a team of researchers in Australia (Gulliver, Fielding & Louis, 2019). Their analysis demonstrated that many campaigns do, in fact, achieve their goals.

While it is not possible to determine whether the goals were achieved because of the advocacy itself, or for some other reason, this analysis indicates that advocacy is able to engage successfully in public interest communication and achieve success. Click on the image to learn more about the analysis of the climate change campaigns and their outcomes.

What happens when advocacy doesn’t achieve its goals?

In many situations interest groups do not feel heard despite free and open opportunities to engage in debate in public arenas. For some activists, their perceptions of failure have led to an increasing use of ‘civil resistance’; often involving breaking the law as part of their advocacy.

And, of course, in other cases advocacy may turn to violence. When public debate is censored, or suppressed, or public arenas of debate are cut off and ignored, individuals and groups can turn to violent means. While research on the effectiveness of violent vs non-violent activism suggests that non-violent activism is far more effective at achieving its goals (Chenoweth & Stephan, 2011), history shows that often activists may find that peaceful advocacy does not lead to success. Consider the dilemma activists are facing in some regions in Eastern-Europe and Central-Asia in their quest to implement safer drug policies and protections for minority groups. The following video from The Drug Reporter features the stories of resistance and survival of organisations and activists fighting for the human rights of vulnerable minorities.

The challenges of engaging in advocacy

As you watch the video consider these questions:

- If you were an advocate on any of these issues, what would you have done?

- What actions would you have taken?

- How would you respond to the crackdown on advocacy in these areas?

- What would you have done if your advocacy was unsuccessful?

An entity with three characteristics. First, that individuals share a collective identity; second, that they interact in a loose network of organizations with varying degrees of formality; and third, that they are engaged voluntarily in collective action motivated by shared concern about an issue (Giugni and Grasso, 2015).

‘The act of persuading or arguing in support of a specific cause, policy, idea or set of values’ (Cox and Pezzullo 2016). Advocacy can be undertaken by groups or individuals (Tarrow, 2011), who together form a movement on the basis of a shared identity (Diani, 1992).

‘A connected series of operations designed to bring about a particular result’ (Merriam Webster Dictionary).

Tactics are the actions used to implement a strategy, which itself is a ‘plan that is intended to achieve a particular purpose’ (Oxford Learner's Dictionaries).

‘The clearly defined, decisive and achievable changes in social actors, i.e. individuals, groups, organizations or institutions that will contribute to the overall campaign goal(s)’ (UN Women 2012).