9 Capital and capacity building

The word capital has many meanings – from a place (e.g. capital city) to a form of punishment (e.g. the death penalty) and sometimes even a posh way of describing an idea (e.g. ‘what a capital idea!’). In this chapter we refer to capital as the accumulation of something – specifically we look at social capital, which brings together people and their relationships, and its close cousin capacity building, which puts social capital to work. Other capitals are economic/financial, human, intellectual, symbolic, cultural and natural. Because social capital focuses on like-minded people coming together for a mutually beneficial purpose it can help in building communities and even making them flourish. Central to all of this lies open and responsive communication which enables people to effectively connect. But because communities are heterogenous, that is made up of multiple interests and publics, individuals need to be open to the perspectives and methods of others, even when they share a mutual goal. You will recall examples of this from the previous chapter on partnerships. Public interest communication is at work when social capital and community capacity building find shared outcomes based on the process of this open, inclusive approach.

Social capital

While Aristotle and other Greek philosophers who spoke of civil society and social relations were among the first proponents of social capital, our contemporary understanding of it was explained by West Virginian school reformer L.J. Hanifan who commented in the early 20th century:

‘The individual is helpless socially … If he may come into contact with his neighbor, and they with other neighbors, there will be an accumulation of social capital, which may immediately satisfy his social needs and which may bear a social potentiality sufficient to the substantial improvement of living conditions in the whole community’. (1916, p. 131-32).

Hanifan then explained that the more “people do for themselves, the larger the community social capital will become, and the greater will be the dividends on the social investment” (1916, p. 138). Broadly, this is still how we understand social capital today. Others have gone on to popularize the concept of social capital such as American political scientist Robert Putnam whose book, Bowling Alone, was about the disconnection to community in American society. At the heart of this was the need for social capital which he defined as having “features of social organization, such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitates coordination and cooperation” (1995, p. 67).

Take for example how a ‘people-centred’ approach to development works for different communities. This focuses on giving local communities ownership and agency to manage their own lives, environments and future. In the Pacific, this is illustrated in this video which flags how different communities and cultures need local input to affect change. This is about communities helping themselves in a wide range of social and cultural roles, from health, environment and agriculture, to human rights.

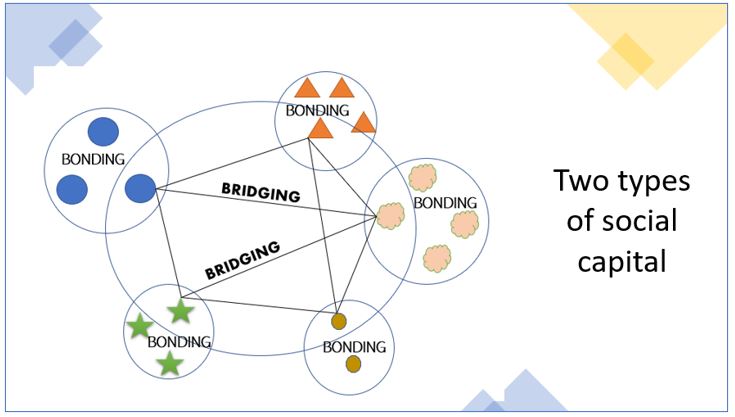

Most scholars agree that social capital links people in one of two primary ways. First, through bonding or linking people together within a group based on a common identity, such as family, close friends or people who share a culture or ethnicity. Second, through bridging, by linking people across different identity groups, such as those in different religions, classes or from different cultural or identity groups.

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (pronounced bored you) argues that “social capital is never completely independent of other forms of capital” (1986, p. 251). He speaks of the power imbalance which lies at the core of social, cultural and human capital — and how individuals are disadvantaged in the capital exchange when access to resources is limited. This means that poorer or disadvantaged individuals or groups can miss out on social capital building – these are often the minority groups or interests we have spoken about elsewhere in the book. And so, “what is needed to make change for the public benefit and in the public interest is the internal capacity and agency to enable social capital to develop and grow plus external supports to sustain it” (Johnston, 2016, p. 132).

These external supports can come from governments at all levels, NGOs or sometimes corporates which can assist the growth and development of social capital in communities. In turn, this can translate into community capacity building, which we look at shortly.

Which of the following words apply to ‘bridging’ social capital?

Language as social capital

Language is an important part of social capital. Shared language is seen to be critical for social interaction which is essential for people to work together for collective action (Claridge, 2020). Claridge says speaking and understanding a mutual language is identified with social identity, trust, participation and belonging. At the same time, a lack of shared language can emphasise difference and division, be a barrier to participation and interaction, and impair reaching common goals (Claridge, 2020). “In a practical sense, a lack of shared language can make communication ineffective and make it difficult to reach mutual understandings” (Claridge, 2020).

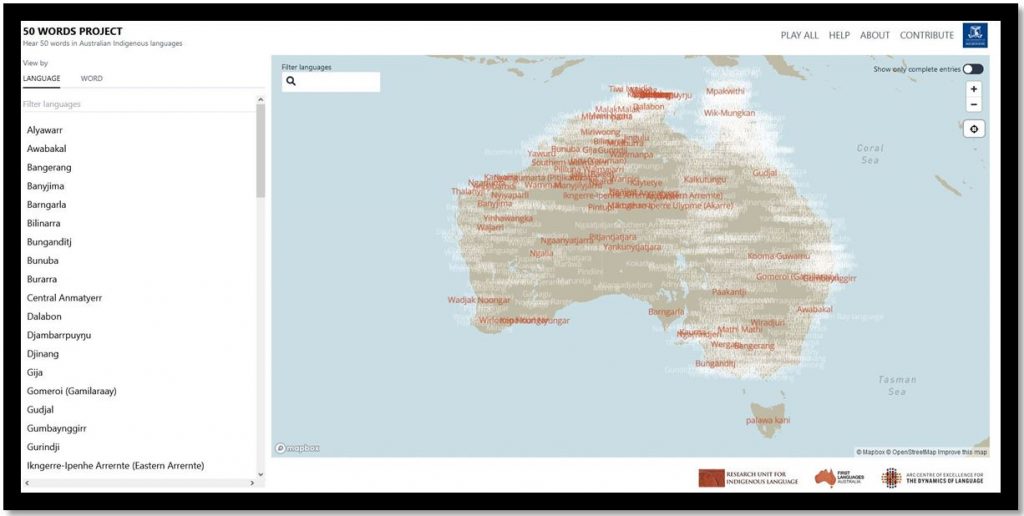

In recent years there has been a resurgence in rebuilding and restoring lesser-known languages or those languages that have fallen into disuse. It is hoped that this will help restore social capital, identity and belonging in groups associated with these languages. One such project – 50 Words – is comprised of 60 Australian Indigenous languages. It has been collated by researchers from the University of Melbourne working directly with Indigenous communities and language speakers from around Australia. The interactive map enables you to read and listen to 50 words and phrases in many languages. Some of these are exchanges, such as: wanyjika-n yanku? (where are you going?) and ngurna yanku ngurra-ngkurra (I’m going home). Try out some of the words and then click on them and hear them spoken for you. There are group activity questions following the diagram, below.

Contributor to 50 Words Kado Muir explained the importance of language:

‘When you lose a language, you lose a worldview. You lose a way of understanding the land on which you are living. You lose an understanding of different philosophies. It makes our lives as human beings a lot poorer if we lose a language.

If you learn a language, you then get access to that particular way of thinking that ties you back to country – back into the dreaming, the creation, and your ancestors. And once you start rewiring your brain in that way, it opens up a whole world of imaginings and possibilities’. (Johnston, 2020).

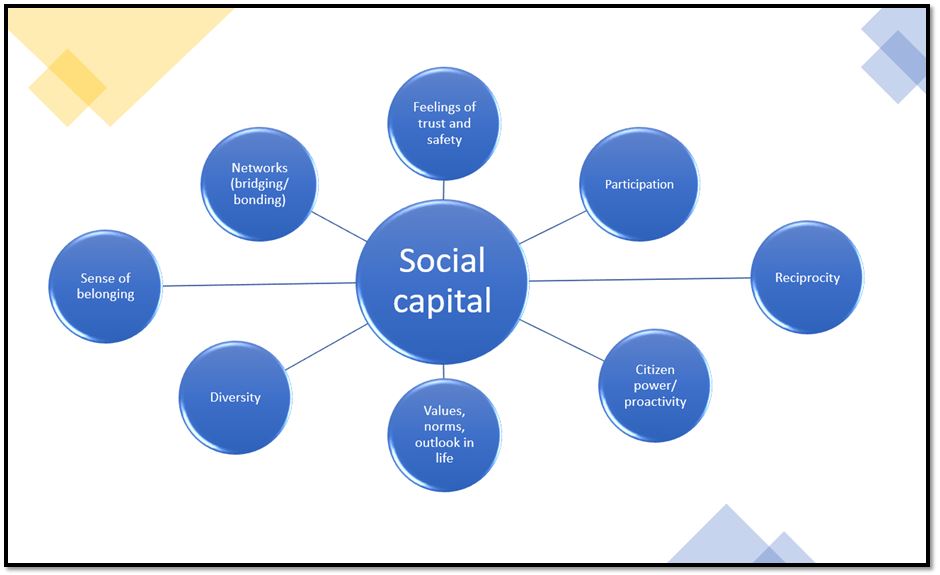

This sentiment is illustrated in the elements of social capital, as seen in the following diagram.

Questions:

- Make a list of the eight outside elements in the social capital diagram and, using these elements, list how regenerating language through the 50 Word project might contribute to the social capital of Indigenous communities?

- What examples of bridging and bonding social capital can you identify? For example, which role did researchers from the University of Melbourne play? Which role did participants such as Kado Muir play?

Community Capacity Building

Community capacity building puts social capital to work. It sees residents working together to achieve goals through communication, leadership, training, policy-making, technical or service assistance, and establishing networks for exchanging resources and ideas. Importantly, capacity building is a ‘bottom-up’ process, which means to be effective it must be driven from within the community, reflecting local circumstances and the needs of the community (Johnston, 2016). This is where partnerships come into play – often between a community and a local government, an NGO or a business (or a combination of these). These larger, usually better-resourced organisations can assist communities which identify their own local gaps, needs, strengths, opportunities, and priorities for development.

The Queensland Government has a ‘Capacity Building Toolkit’ to assist rural and regional Queenslanders develop and maintain sustainable, liveable and prosperous communities. It lists commonly accepted keys to success as:

- Having local people who are willing to ‘drive’ action.

- Developing ‘allies’ — people or organisations who can help.

- Using the existing assets of the community.

- Having a small visible success within six months.

- Having access to some resources.

- Celebrating successes.

- Establishing and maintaining good communication channels.

All of this includes looking within the community, at its collective social capital and the skill-sets of individuals, which may then be facilitated by an external partner. At the same time, a high level of community involvement can do the following:

- Raise community awareness about an issue or a project.

- Identify what will work and what will not.

- Verify ideas or information.

- Tap into new ideas and expertise.

- Provide avenues for dialogue.

- Build community support.

- Provide feedback or suggestions.

These elements were in force in a Victorian capacity building project in the 2000s when the regional town of Clunes sought government support to set up their very own ‘Booktown’. Read about their success story here (adapted from Johnston, 2016). You can check out the event here.

Case study: Clunes community capacity building

Clunes is a small rural town in central Victoria, 139 kms from Melbourne. Though it was a booming gold-mining town in the nineteenth century, attracting miners and merchants from around the world, when the gold ran out the town went into decline with the population falling to less than 1,000 residents at the start this century. Migration away from the town to cities and larger centres, plus a devastating ten-year drought, impacted harshly.

The fate of Clunes changed in 2007 when a group of four residents met to promote the idea of a town-focused renewal strategy based on cultural development. They created the not-for-profit community organisation ‘Creative Clunes,’ which set its sights on developing the town around the European concept of second-hand and antiquarian bookshops. Clunes secured patronage from three levels of government – a success attributable to “the pool of social capital” in the town (Franks, 2015, p. 112). And, in 2016, the Victorian government announced continued funding for Clunes to the tune of $240,000 (Victorian Government, 2016).

In 2012, Clunes achieved membership of the International Organisation of Booktowns, becoming the 15th international booktown in the world. This concept has been shown to “revitalise communities via multiplier effects from a book-based economy, cultural tourism and increased social capital for communities,” (Franks, 2015, p. 7). The Clunes annual book town weekend festival attracts in excess of 18,000 visitors, with over 60 book-traders involved (Brady, 2012). “In every sense … Clunes becoming a booktown has been a community-building activity where all the players have socially benefited’ (Brady, 2012, p. 14).

Questions:

- Go to the bullet points from the ‘toolkit’ above and consider how Clunes illustrates community capacity building at work?

- Why do you think governments back regional enterprises like this one and why might they view this as in the public interest?

- Can you explain how social capital can translate into capacity building in a regional township?

Another town that has become well known for its capacity building around community-government partnerships is Portland in the United States. Consider the capacity building it has achieved by doing some internet research. A starting point is here at this city of Portland site https://www.portlandoregon.gov/civic/28381.

An entity consisting of diverse parts or things that can be very different from each other.