5 Ethics

Those who’ve studied ethics previously will be aware that there are rarely simple solutions to ethical dilemmas. This actually sits well within the framework for this book as public interest communication is as much about reflexive practice and challenging existing thinking as it is about coming up with absolute answers. Rather, public interest is often about balancing different interests, and ethical philosophies can provide conceptual toolkits to assist this process. As US ethics scholar Russ Shafer-Landau says: “We must know how to balance options that generate different goods, on the assumption that there is more than just one kind of intrinsic value” (2013, p. 612).

Johnston (2016) points out how utilitarian concepts might at first seem to equate best with notions of public interest because of the utilitarian principles that actions are right if they lead to the greatest possible good (or the least possible bad). However, this presents problems with also balancing the needs of pluralist and diverse societies where the majority can overlook the interests of minorities or those who are less represented in the system. Therefore, a shift away from universalising – in which most people might ‘win’ – is found in the understanding that plurality and heterogeneity lie at the heart of many contemporary societies. This presents a logical interface with how we view society as many publics, where in any given interest clash, there will be publics and counter-publics that see the same problem or issue very differently.

US Scholar Linda Hon neatly sums up the links between public interest communication and ethics. She argues:

Public interest communications is distinguished by a commitment to communication that advances the human condition. Public interest communications embraces the vision of ethicists who make explicit the priority of shared human values and rights over vested interests that deliberately seek to obfuscate or have as their goal the denial of any person or group of people the fundamental human rights of dignity, freedom, equality and quality of life including health and safety. (cited in Fessmann, 2016, p. 13).

The approach sits comfortably with Dewey’s ‘pragmatic idealism’ outlined in an earlier chapter. However, we do note it is aspirational in nature and, as we move forward, we find the messy nature of society rarely makes things this simple in ethical dilemmas.

Podcast: Jess Laven on A Place to Call Home

Listen to the following podcast by Jess Laven, which explores the wicked problem of homelessness around the world.

The need to find balance when faced with ethical dilemmas will oftentimes place ethics and law at odds with each other; sometimes ‘national interests’ in law will compete with humanitarian interests; and most definitely publics will clash with each other. The issue of asylum seekers provides a good example. The Ethics Centre considers this situation in Australia while the Centre’s Executive Director Simon Longstaff says ‘asylum is fundamentally about the public and personal good of human safety’. Among the many questions raised on this issue is whether or not governments will allow asylum seekers to receive refugee status and on what grounds will they make such determinations?

Let’s look at a case study.

Case study: The Murugappan family

This is a story of a Tamil family who sought refugee status to stay in the town of Biloela in Queensland, Australia. The Murugappans are a family of four: mother Priya, father Nades, and their two daughters Kopika and Tharnicaa. The family – reported by the BBC as Australia’s “most famous asylum seekers” – were moved from Biloela and held in detention for four years. A highly successful social media campaign, based around the hashtag #HometoBilo, a petition with 350,000 signatures, and a change of government in 2022 resulted in a happy ending for the family when they were granted permanent visas and allowed to return to Biloela to live. It was heralded a win for “people power”. It did not result in a change to immigration policies but was considered on the basis of “complex and specific” circumstances.

Do some preliminary research on this case study and review previous chapters, then work through the following questions:

- What were the main clashing interests in this case?

- Who were the main publics and counter-publics in this conundrum?

- If the town of Biloela had consistently supported the family staying there, why do you think the former Australian government stood firm on its decision to not grant the family a permanent visa?

What is ethics?

Ethics itself is a branch of philosophy which investigates ideas, concepts and arguments around what constitutes right and wrong / good and bad. Approaches to understanding what is ‘right’ and what is ‘wrong’ as well as what moral concepts such as justice, duty and virtue mean, differ across cultures and within communities. But, as we have seen elsewhere in the book, the idea of thinking in binaries can be very delimiting.

Some ethics scholars such as Martin Peterson (2023) suggest that some acts are neither right nor wrong, but rather they are a bit of both. He calls this ‘the gray area’ of ethics which moves away from the binary thinking where every situation has a wholly right or wrong pathway. Peterson (2023) talks about “gradable notions of right and wrong” which take into consideration nuance within moral conflicts. Consider the case of the Murugappan family, illustrated above, in which an absolute position of ‘wrong’ was held by the Australian government during their detention because they had broken Australian immigration law. However, when the public support for the family, the need for flexibility, and consideration of the case on its merits were evaluated, the level of ‘wrongness’ was balanced against the level of ‘rightness’ of their particular case and they were allowed to return to their community.

As the above case study demonstrates, ethical dilemmas are woven into the decisions made by individuals, organisations and institutions every day. It is not surprising then, that the examination of ethical complexities has been a preoccupation of thinkers since humanity’s first records were created. This timeline provides a brief history of key moments in the evolution of ethical theorising around the globe.

There are many types of ethical philosophies: utilitarianism, summarised above, sometimes called consequentialism; deontology; and virtue ethics are the three best known. They are explained here, also in a crash course in this video on virtue ethics, and in the following video about Virtue Ethics by The Ethics Centre. This video considers the question ‘What makes something right or wrong?’ As The Ethics Center notes;

One of the oldest ways of answering this question comes from the Ancient Greeks. They defined good actions as ones that reveal us to be of excellent character. What matters is whether our choices display virtues like courage, loyalty, or wisdom. Importantly, virtue ethics also holds that our actions shape our character. The more times we choose to be honest, the more likely we are to be honest in future situations – and when the stakes are high. (The Ethics Center, 2021).

Codes versus virtue ethics

In our consideration of ethics and public interest communication we will focus on virtue ethics; in particular on how ‘agent based’ ethics sits in contrast with professional codes of ethics. Because codes are based on rule-following they fall into the category of deontology.

The two pathways can be understood in the following ways:

- Code-based framework (Codes of Ethics) – This is considered a profession or industry’s contract with society. It is part of a profession or industry’s internal self-regulation which also provides a common reference point amongst members. Codes require practitioners to interpret the rules which are not usually explained in detail. Codes may be known as rule-based or action-based ethics.

- Agent-based ethics (Virtue Ethics) – This leaves ethical decision-making up to the individual to use their own internal barometer of what is ethically right and wrong, based on their character, motivation and, importantly, their habits of practice. It is based around ideas from Greek philosopher Aristotle in determining what was virtuous behaviour in leading a virtuous life.

Both ethical routes provide pathways to interpret public interest. Codes of ethics often incorporate how to work for the public interest into their aims. For example, a global study of public relations codes by Johnston (2016) found 31 out of 84 codes of ethics or conduct made reference to ‘public interest’ or ‘interests of the public/s’. The study found that many countries cited two international codes: the Code of Athens and the Code of Lisbon , which were created by the International Public Relations Association (IPRA) in 1965 and 1978 respectively. Here’s how they incorporated the public interest.

The Code of Athens calls for a balance between the interests of public and the organisation: “To act, in all circumstances, in such a manner as to take account of the respective interests of the parties involved: both the interests of the organization which he serves and the interests of the publics concerned.”

The Code of Lisbon on the other hand distinguishes between public and individual interests, saying: “He/she likewise undertakes to act in accordance with the public interest and not to harm the dignity or integrity of the individual.”

These, and other codes, provide useful ways of presenting a summary of public interest. However, they are also limited in what they can achieve. Some PR scholars have advocated using virtue ethics over codes because of the unresolved conflicts surrounding interests to client and the public found within codes (see Harrison and Galloway, 2005, in Public relations ethics: A simpler (but not simplistic) approach to the complexities). More broadly, codes have been criticised for a number of reasons including lacking the capacity to anticipate situations; being too simplistic; not providing real solutions; being poorly communicated; not being able to impose sanctions or punish breaches; and by being vague, imprecise and making lofty statements.

Virtue ethics on the other hand provide an alternate pathway drawn from the actor rather than the action. Virtue ethics call on the individual to use good judgement in ethical decision making, rather than being prescribed by a professional or industry code. They call on Aristotle’s idea of moral virtue based on ‘habits’ that result in doing virtuous acts. Instead of focusing on the question of ‘what should I do?’ when faced with an ethical decision, Aristotle’s primary concern was ‘how should we live?’ A major strength of this agent-based virtue ethics therefore lies in embedding ethical behaviour into our lives, placing virtue ethics beyond the industry or profession. This sits best for public interest communication which is not industry-specific but rather a way of thinking and doing communication (Johnston, 2018).

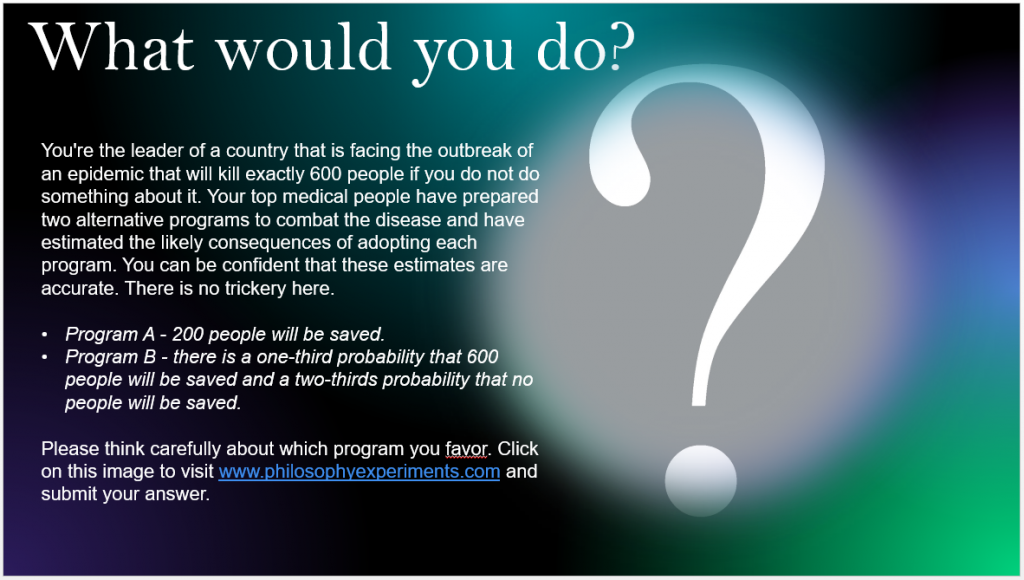

Of course, this can be very difficult to disentangle in practice. One way of imagining how we might respond to ethical choices is to engage in ‘thought experiments’. Centuries of philosophical debate around ethical issues has led to the development of classic thought experiments on dilemmas which challenge our ability to make ethical choices.

Test yourself with the following experiment and visit this site to delve more deeply into how you, and others, make ethical choices in a range of complex scenarios.

Managing (Dis)information

In reality the question of code vs virtue ethics is not a simple ‘either-or’ decision. Rather, both can be useful to the communication practitioner and codes are a part of professional life and should be part of ethical training. The virtue ethics approach however is most useful when we decouple ethics from the professional role in pursuing public interest communication as individuals trying to do the right thing.

An essential part of effective public interest communication is to practice active listening while considering the validity of the information which informs individual’s ethical positions. But what happens when false or misleading information is introduced into a debate? How can that affect our ability to use judgement in our ethical decision making? We have heard more and more about the impact of disinformation and false arguments on democratic debate and beliefs around important issues such as vaccination. Consider the long running debate surrounding the impact of disinformation on the 2016 U.S. Presidential election campaign.

However, detecting these tricks and identifying how they can affect our own ethical decision making can be very difficult. Can you spot it when it happens to you? Watch and play the following interactive ‘Debate Den’ video to find out.

When individuals reflect on what they have learned and then consider how the implications of their learnings can impact the broader context.

The philosophy which argues that an action is right if it results in the happiness of the greatest number of people in a society or a group.

Binary thinking refers to seeing things as opposites, black-and-white, right-and-wrong, with no middle ground, thus ignoring the nuances, contexts and complexities that exist within any given situation.

The doctrine that the morality of an action is to be judged solely by its consequences.

The study of the nature of duty and obligation.

A character-based approach to morality which argues that we acquire virtue through practice and character traits rather than fulfilling duties