10 Social enterprises

Social enterprises find a sweet spot between being a business and a nonprofit. These are organisations like Thank you, Who Gives a Crap, OzHarvest, Betterbooks and many, many more which use different models to work to benefit the world through share-profits, fairtrade, assisting developing communities, recycling and repurposing, and so on. Their purpose, or mission, is always to help society or the environment in some way through related business activity. There are many definitions for social enterprise, but we really like this one from the online magazine The Good Trade: “A social enterprise is a cause-driven business whose primary reason for being is to improve social objectives and serve the common good.”

No surprise that many definitions and descriptions touch on social enterprise as serving common good or public benefit. We don’t have to look too far then, to find the link with public interest communication. Not only are these enterprises driven by a social mission – such as healthcare, safe drinking water, sanitation, renewable energy, job creation and access to education – their reliance on public support means they need to effectively communicate their initiatives to make these happen. One example of a not-for-profit organisation that seeks to achieve positive social outcomes is ‘Share the Dignity’: a women’s charity which works to benefit those in crisis experiencing period poverty. Listen to the following podcast to find out more about what this organisation does and seeks to achieve.

Podcast: Claire Chuyue Chen Share the Dignity

In this podcast Claire explains how the widespread experience of homelessness in Australia can result in ‘period poverty’, where women and girls do not have access to period products. ‘Share the Dignity’ organisation forms partnerships with stores to obtain donations of sanitary products, as well as individual donations of products and funds. This makes a meaningful difference to the lives of many Australian girls and women, thousands of whom experience homelessness at any one time.

Of course, Australia is not the only country where this can happen. Other organisations such as ‘Sanitary Aid Initiative’ in Nigeria also work to raise awareness of this issue and support communities to overcome period poverty. Watch the following video to find out more about how organisations are engaging in public interest communication to alleviate this issue in Nigeria.

Blended value proposition

Social enterprise pioneer Kim Alter says the rise of social enterprise, along with corporate social responsibility, social investing, and sustainable development illustrates the blend of financial, social, and environmental value. She calls this “the blended value proposition” (2007, p. 14). She says social enterprise sees a shift from thinking about nonprofits being solely responsible for social and environmental value and for-profits for economic value, to an understanding that both types of organisations can generate all three value sets. She clarifies what constitutes a social enterprise:

‘Though subtle, and subject to debate, the defining characteristic is that an income generating activity becomes a social enterprise when it is operated as a business. The following characteristics apply: the activity was established strategically to create social and/or economic value for the organization. It has a long-term vision and is managed as a going concern. Growth and revenue targets are set for the activity in a business or operational plan. Qualified staff with business or industry experience manage the activity or provide oversight, as opposed to nonprofit program staff’. (Alter, 2007, p. 17).

Earned Income Activity versus Social Enterprise

The following examples of Washington DC’s ‘Zoo Doo’ and Thai zookeeper’s innovative use of elephant dung further clarify the difference between a social enterprise and other forms of business (Case study from Alter, 2007, p. 17-18).

‘Zoo Doo’ case study

The National Zoo in Washington DC sells Elephant dung to the public as exotic fertilizer. Although the humorous product is popular among local organic gardeners, the ‘Zoo Doo’ venture is not treated as a business and the income it earns is insignificant. Opportunities to scale Zoo Doo into a viable enterprise by selling the product in nurseries and gardening catalogues, as well as adding other ‘zoo products’ to the line have not been realized. Instead Zoo Doo functions as an innovative public relations and marketing strategy used to attract visitors and patrons to the National Zoo. The small amount of money it generates is considered a plus.

Using the same raw material, Zookeepers in Bangkok, Thailand turned their Elephant dung into lucrative business. The Thais transform the animal excrement into high-quality handmade paper which are sold in stationary stores, nature shops, and used in premium paper products in domestic and export markets. The enterprise employs several people who process the organic pulp to produce handmade paper. To keep up with demand, Thai zookeepers source dung from other zoos and elephant habitats. Unlike Zoo Doo, the Elephant dung products are not advertised to consumers as such; rather, socially conscious consumers are sold on organic nature of the product and the fact that proceeds from sales are used to fund zoo activities and animal protection organizations.

Alter’s social enterprise organisation Virtue Ventures provides some excellent examples of how social entrepreneurs work on social enterprises all over the world. (Tip: when you’re researching social enterprise also look up social entrepreneurship as the two are often used interchangeably.) You’ll find when you begin looking into social enterprises that there are intersections with other key themes covered in this book: publics and stakeholders, partnerships, social capital and capacity building. Social enterprises thus provide business contexts for how these themes may be operationalised or put into practice in a business sense.

Go to Virtue Ventures website page called ‘Onsight’ by clicking here and answer the following questions:

- How does this model use communication to assist social enterprise ventures?

- What features are useful about the 360degree and VR technology provided on this platform that we could associate with public interest communication?

Social enterprise models

The focus on assisting minority groups and those who may be poorly resourced, plus finding solutions to problems, makes social enterprise a neat fit with public interest thinking. Oxford University scholar Tanja Collavo says solutions to social and environmental problems can occur through innovation, the creation of employment opportunities, the development of skills in marginalised or disadvantaged communities, and the creation of business that generates social impact (Collavo, 2017).

These different approaches have been categorised in the following three models (Cadwell, 2017):

- The innovation model – e.g. companies that develop clean energy technology to rural African communities, such as Solar Sister

- The employment model – e.g. companies that employ artisans via fairtrade initiatives, such as Faire Collection

- The give-back model – e.g. companies that give a share of profits to a cause or community for purchases made, such as Betterworldbooks

Some social enterprises have characteristics of two or three of these. The Thai elephant example, above, certainly combines the first two. Read through the next example which has elements of all three.

Big Issue

You might have bought a copy of the Big Issue from a street vendor. This social enterprise is rich in innovation, creates jobs through micro-businesses, plus puts back the funds it makes into the community. First and foremost, the Big Issue runs social enterprises which create work opportunities for people who are unable to access mainstream work. These people come from many different circumstances: they may be homeless, long-term unemployed, intellectually or and physically disabled, have a mental illness, drug and alcohol dependency, or be a victim of family breakdown.

Big Issue Australia enterprises include:

- The Big Issue magazine – Created by an editorial team, this fortnightly quality magazine is made available for vendors to buy at $4.50 per magazine. Vendors then sell the magazine to customers for $9 each.

- The Women’s Workforce – The Women’s Subscription Enterprise employs marginalised and disadvantaged women to pack and sell subscription copies of The Big Issue magazine.

- The Big Issue Classroom – Provides workshops for school, tertiary and corporate groups providing real-life insights into homelessness and disadvantage.

- The Community Street Soccer Program – Links coaches and communities to run two-hour street soccer games.

In addition, the ‘Homes for Homes’ initiative, is a sustainable and collaborative way of raising funds for social and affordable housing through donations from property sales (See the ‘About us’ page at https://thebigissue.org.au/about-us/).

The Big Issue operates all over the world. It began in the UK in 1991 – now 30 years later it is one of the oldest and biggest social enterprises in that country.

Test yourself on the following examples to see whether you can identify which of the social enterprise models are represented in the flash cards.

Social enterprises as a four-part strategy

Social enterprise is a practical way of making social change happen through business activity. A nifty way of thinking about social enterprises that have been successful, including those we’ve considered in this chapter, is by considering four key social enterprise elements:

- making money,

- making a difference,

- making the magic,

- making it work.

This ‘putting the puzzle pieces together’ approach developed by the Australian Business Planning guide for social enterprises is intended to remind those interested in starting a social enterprise that the twin business and social aims call for the alignment of many things: a strategic plan; managing operations, finance, compliance and people; and having effective and efficient internal and external communication.

Theoretical intersections

We can further strengthen our understanding of social enterprise by considering some related theories.

Corporate social responsibility

CSR’s triple bottom line – people, profit, planet – reminds us of the different aims in combining business with social and environmental needs and expectations. While most corporates are not social enterprises, being socially responsible has become a focus for working beyond what was once known as ‘the bottom line’ – which simply meant making a profit. There are many definitions for the complex notion of CSR. Some common features include:

- the balance between financial, social and environmental responsibilities,

- the voluntary nature of CSR (although there are increasing regulations and expectations forcing companies to act),

- the involvement of diverse stakeholders. (Johnston & Glenny, 2021).

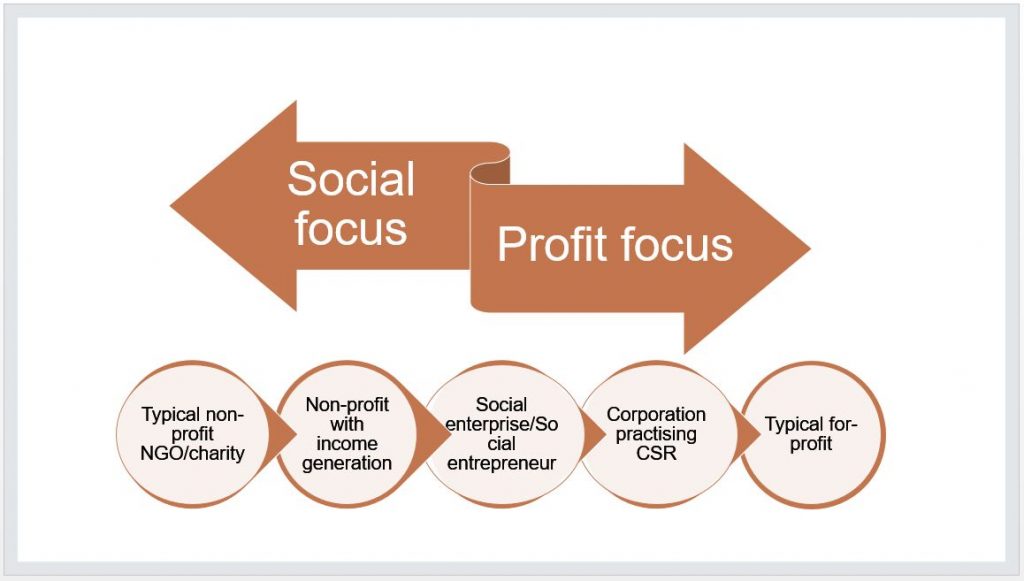

The following diagram, adapted from Alter’s ‘hybrid spectrum’, shows a spectrum of business activity and CSR’s relationship to social enterprise.

Enlightened self interest

This is a theory about how democracy works, but also has some strong messages for the hybrid business model of social enterprise. It is about finding a balance between individualism (self-interest) and common good (public interest). “The idea behind this theory is that the wider public interest and individual interests are not mutually exclusive—they can overlap,” (Johnston & Glenny, 2021, p. 284). Underpinning this concept is that as part of society an individual will contribute to wider social developments and take part in the social contract. The idea of the social contract has been popular for centuries, promoted by various philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau as an explanation of why individuals accept some obligations in exchange for social benefits. This theory is often associated with the idea of ‘doing well by doing good’, as explained here in a Harvard Business Review interview. The interview also links this concept to CSR.

Of course, times of major upheaval – such as a global pandemic – can led to widespread suffering which can undermine the social contract. Indeed, some people have argued that the pandemic has shown a need to ‘reform the social contract’ after COVID-19, particularly given fears of increasing authoritarianism around the world. Take a look at the following short video filmed at the World Economic Forum. What do you think? Do we need to reform the social contract post-pandemic? If so, how should we do it?

An implicit, hypothetical, or actual agreement or compact among members of a society to cooperate for social benefits, or between rulers and the ruled, defining the rights and duties of each.