II.3. CSR and Communication

Franzisca Weder

Let’s get back to the idea of communication being the core of all processes in the society. Communication was described in the first chapter of this second part of the book as the sending and giving as well as receiving of information and messages – or the exchange of ideas, meaning, information. But we learned that communication also enables individuals, groups, communities, organizations and societal systems to create meaning and sense, to narrate and socially construct the world around them.

In the second chapter of this second part of the book, we also learned about strategic communication and the general research paradigms. We also briefly explained that strategic communication research mostly looks at:

- the sender of information, so who is communicating (individuals, organizations, institutions, corporations, etc.), and at

- the receiver of the information (again, another individual, a group, a “target audience” or a certain segment of the public – or ‘stakeholder’).

Photo by SHVETS production on pexels.com

However, we also explored that organization, every corporation as well as every political institution or environmental movement is embedded in the society via communication. Thus, organizations communicate with their employees or members (internal communication), organizations communicate with their stakeholder or target audiences (via public relations, advertisement or media reporting) and organizations participate in societal discourses, in offering information about climate change related problems and their answer (i.e. their CSR or sustainability strategy) on their website (for example, the European Energy Corporation: OMV) or in various form of so called CSR or sustainability communication, which will be explored in part III of this book. For now, we will have a look into CSR communication research and answer the question of what phenomena researchers looked at so far.

Over the past decades, not only the Top 500, the big corporations like Coca Cola or Nestlé realized that they are responsible for not only doing good, but communicating about it. Even small business, like a local bakery in Australia (check Baker’s Delight CSR endeavors) started to understand, that responsibility needs to be communicated – and by the same time, that communication needs to be responsible, and sustainable; it’s not a short term marketing-gag, it is about a meaning making process, about the creation of a narrative that goes beyond a short-term throw-out of a “green-image” (we will talk about greenwashing later, see chapter III.1 and chapter III.2).

Looking at the research area that studies and analyses responsibilities that are allocated and taken via communication and therefore various forms of CSR communication, we see that most of the literature analyses predominantly communication of CSR, related activities or concepts like sustainable development or ESG and how they are presented and represented in ‘classic’ forms of strategic communication (reports, websites etc.). This stands for a functional, pragmatic and therefore instrumental perspective on communication, where CSR is perceived as one way to reach economic goals. Check this overview:

Theoretical approaches to CSR Communication

- Instrumental approaches (CSR = a mere means to the end of profits) (Friedman 1970; Porter & Kramer 2002; 2006)

- Integrative approaches (CSR = integration of social demands) (Sethi1975; Preston & Post, 1975; Mitchell et al., 1997; Carroll, 1979)

- Ethical approaches (CSR = ethical values/obligation) (Freeman, 1984; Brundtland Report 1987)

- Political approaches (CSR = social duties/rights & participation in a certain social cooperation) (Davis 1960; Donaldson & Dunfee 1994; Andriof & McIntosh 2001; Matten & Crane 2005; Garriga & Melé 2004)

Today, the field of scholarship that CSR represents is a broad and diverse one, encompassing debates from many perspectives, disciplines, and ideological positions. (Crane et al., 2008, p. 7; Diehl et al., 2017; Golob et al., 2013; Elving et al., 2015). But as stated, the functional, instrumental understanding of communication dominates related conceptualizations of responsibility (CSR) and CSR communication (similar to strategic communication in general) (Bjorn et al., 2018; Kuntsman & Rattle, 2019), which also includes communication of and about sustainability or ESG (Weder et al., 2019a; Newig et al., 2013; Genc, 2017), evaluated and affirmed by an increasing number of studies focusing mainly on sustainability reporting (Chaudhuri & Jayaram, 2018) or recommended media channels for CSR and sustainability Communication (Huang et al., 2019; Maltseva et al., 2019; Burns, 2015).

However, there are various approaches to CSR and thus to CSR Communication. Integrated approaches to CSR as shown above go hand in hand with integrated approaches to strategic communication, as well political or ethical approaches are in line with a more critical understanding of communication, with a stronger focus on stakeholder engagement and / or participation.

The overview of CSR communication research also shows that there seems to be a specific focus on communication strategies. Based on the existing understandings of strategic communication and the paradigms discussed in chapters II.1 and II.2, the literature and concepts of CSR communication can differentiate between the following strategies (based on a classic differentiation by Grunig & Hunt for Public Relations):

- Stakeholder Information Strategies: Inform stakeholders about favourable corporate CSR decisions and actions! (information focus, one-way communication, sense giving, decided by management, stakeholder either support or oppose)

- Stakeholder Response Strategies: Demonstrate to stakeholders how the company integrates their concerns! (two-way communication, but asymmetric, sense making & sense giving; stakeholders respond to corporate actions, evaluated with surveys, opinion polls etc.)

- Stakeholder Involvement Strategies: Invite and establish frequent, systematic and pro-active dialogue with stakeholders, i.e. opinion makers, corporate critics, the media, etc. (two-way, symmetric communication, sense making, co-construction of CSR efforts, stakeholders are involved, participate and suggest corporate action, negotiations / integration with stakeholders)

What can we take away from here?

Firstly, again, CSR communication research is influenced by the two paradigms. Secondly, apparently CSR communication is different. Because, it’s not two variations of communication that is dealt with, it is three!

What does that mean – and what does that mean for our further considerations of strategic communication in the area of CSR and sustainability?

The third strategy that adds to a primarily pragmatic and functional understanding and a rather constructivist or constitutive understanding of mainly organizational communication is a more ‘radical’ approach to communication. This includes negotiations, participation and engagement as well as long-term planning and as such, ‘sustainable communication’ as going beyond the two existing pathways. So apparently, it is not only about what is communicated and to whom and in which channel – but it seems to be even more relevant to think about how it is communicated! Accordingly in recent research and theoretical conceptualizations of CSR communication, the quality of communication is increasingly debated.

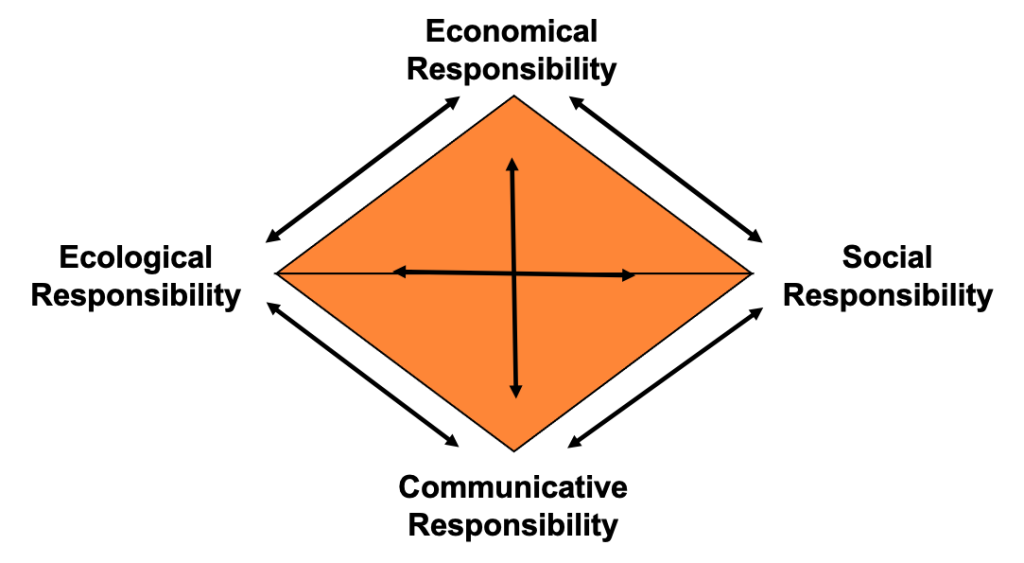

The quality and thus ‘communicative responsibility’ was firstly captured in the concept of the quadruple bottom line of CSR (Karmasin & Weder, 2008):

Graphic by Franzisca Weder

If communication becomes an area of responsibility, organizations are challenged to engage in dialogues with stakeholders in various issue arenas, which puts more attention to the character of CSR communication, related standards and normative frameworks. Following the idea of ‘communicative responsibility’, more recently sustainability was introduced as such a norm or normative framework for stakeholder communication (Golob et al., 2013), stakeholder dialogues and organizational negotiation processes about the dimensions of the allocation and taking of corporate responsibility. Weder et al., 2019, for example state that sustainability as a normative framework for CSR communication offers a broader perspective on environmental and social issues like resources, diversity, workplace security and communicative behavior itself. It definitely leads to an integrated perspective on CSR communication processes and structures (i.e. Diehl et al., 2017; Golob et al., 2017). Today, it is obvious that there was a shift from CSR communication research predominantly focusing on information and the instrumental use of communication to present CSR related activities to the stakeholders and specific audiences to impact orientation. With bringing in a more radical perspective on communication and thus a critical approach to CSR communication understood as co-creation and sense-making, as negotiation processes related to a normative framework, CSR communication should no longer be seen solely as the communication about social, economic and environmental responsibility, so of normative frameworks (Morsing, 2017).

Much more, the ‘fourth pillar of CSR’ is not only discussed in the sense of an obligation or responsibility to communicate, but rather as a normative framework for CSR communication in the future. Only if CSR communication is responsible itself, which means being sustainable, transparent, objective, authentic and trustworthy, it can have an impact. CSR communication then encompasses integrated practices to communicate about CSR activities, communicative practices to identify responsibilities (evaluation, stakeholder involvement, responsibility communication), as well as values and normative frameworks to communicate responsibly (safeguard, beware of ‘greenwashing’, communicative responsibility) (Weder et al., 2019).

CSR communication has an increasing impact on issue life cycles and on the establishment of normative frameworks like sustainability, morality in consumer behavior and decision-making processes as well as internal organizational processes and perceptions and thus organizational culture. This has to be recognized and taken into account in future CSR communication education and training, as well as research and practice.

We summarize:

Based on the understanding that an organization is communicatively embedded in the society, the organization is not only responsible for their action and behavior in an environmental, economic and social dimension but also for their (strategic) communication. Apparently sustainability seems to be a norm or guiding principle to secure the quality of CSR communication in terms of its impact. In the next chapter, we will further explore the status quo of sustainability communication research and how (much) the paradigms discussed come into play.