12 Activism, lobbying and corporate social responsibility by Airbnb – before, during and after COVID-19

Dorine von Briel, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Sara Dolnicar, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Please cite as: von Briel, D. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) Activism, lobbying and corporate social responsibility by Airbnb – before, during and after COVID-19, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.) Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland. DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14204561

Corporate social responsibility

Corporate social responsibility can be defined as “business firms contributing in a positive way to society by going beyond a narrow focus on profit maximization” (McWilliams, 2015: 1-4). The key characteristic of corporate social responsibility is good citizenship; making a contribution to society within the framework of the current value system of a society.

Many organisations around the world have embraced corporate social responsibility and report activities to their stakeholders. Starbucks, for example, signed up to the Sustainable Coffee Challenge, committing to sourcing 100% of its coffee from sustainable providers by 2020. Starbucks also committed to sourcing all of its products from ethical and responsible suppliers by 2020 (Starbucks, 2020).

Airbnb’s first notable corporate social responsibility initiative was a 2016 Signing College Day in collaboration with Michelle Obama and the United Fund (Airbnb, 2016a), encouraging students to pursue higher education and offering scholarships, with a focus on students of colour. Airbnb Connect – an initiative launched in 2016 – helps underrepresented minorities transition into employment in the technology sector (Airbnb, 2016b). Airbnb also regularly donates to local governments to fight homelessness. In New York, for example, Airbnb donated USD $100,000 to an association that provides temporary emergency shelter for families experiencing homelessness (WIN, 2020). It assisted the same association by recruiting volunteers among Airbnb members to help women find employment and children with their education (Cam, 2016). In San Francisco, Airbnb made donations of $5 million (2018) and $2 million (2019) to local organisations fighting homelessness (Said, 2018; Kerr, 2019). It also donated $25 million to the state of California in support of affordable housing and small businesses (Khouri, 2019).

The most successful of Airbnb’s corporate social responsibility initiatives is the Open Homes program, which leverages Airbnb’s access to millions of spaces around to world to assist people in need (Dolnicar & Zare, 2021). For example, in collaboration with the US Federal Emergency Management Agency, Airbnb educates hosts about possible emergencies such as natural disasters (Airbnb, 2017a), and provides access to people displaced from their homes in such situations. Airbnb achieves this by alerting member hosts in affected areas of the emergency and asking them to make their spaces available for free or at a reduced cost. In these instances, Airbnb also waives its service fee (Airbnb, 2017b). In 2020, Airbnb activated this network at least twice: making space available for relief workers helping locals displaced by the devastating Australian bushfires (Airbnb, 2020a), and providing accommodation to over 100,000 COVID-19 responders and health workers globally (Airbnb, 2020b). Airbnb extended the Open Homes program to medical stays in 2018; partnering with the Make a Wish Foundation to help children with cancer (Airbnb, 2016c), the Fisher House Foundation to help veterans, and Hospitality Homes to help patients needing housing (Airbnb, 2018).

In 2020, after Airbnb announced its intention to become a public company, it launched two projects ensuring it would keep communities – rather than shareholders – at the heart of all its activities (Ihnatov, 2020). The Airbnb Host Advisory Board consists of 17 hosts representative of the host community in the United States. The purpose of the Board is to communicate community interests and concerns to Airbnb executives (Stevens, 2020). The Airbnb Host Endowment is a fund financed directly by Airbnb stocks to support host communities (Airbnb, 2020c). Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky stated that “the endowment will provide support in areas including education, financial resources, and much more”. The Airbnb Host Advisory Board will meet with Airbnb monthly; among its responsibilities is to make suggestions on how funds from the Endowment should be invested (Stevens, 2020).

The initiatives discussed above contribute to society and are aligned with current societal norms. They do not financially benefit Airbnb, and do not appear to offer any strategic benefits to the business, except for potentially improving Airbnb’s image.

Airbnb also engages in corporate social responsibility initiatives that do provide strategic benefits. In 2014, Airbnb launched the Shared City Project (Chesky, 2014), through which it selects one city each year and directs all service fees generated in that city towards improving the local community. The inaugural city was Portland, Oregon. The Portland Shared City Project built shared offices for local start-ups and distributed free smoke alarms to Portland’s hosts, as well as providing them with free emergency training to respond to emergency situations. This project benefitted Airbnb by fostering better fire safety and more crisis-resilient hosts. Airbnb’s choice of Portland was interpreted as being strategically motivated because Airbnb views Portland’s regulatory framework for short-term rentals as ideal (Ferreri & Sanyal, 2018). The narrative that Portland’s mayor was rewarded for a favourable regulatory framework overshadowed the fact that this initiative genuinely benefitted both the local Portland community and Airbnb.

Similarly, the Country Pub Project restored five of Australia’s favourite old outback pubs (Airbnb, 2020d). It benefitted the locals, who saw iconic pubs at the centre of their townships returned back to their former glory. The publicity surrounding the restored pubs attracted tourists who otherwise would not have travelled to these remote locations, and who most likely stayed at Airbnb-listed properties.

Activism

In contrast to corporate social responsibility, activism does not operate within the existing societal value system. Rather, the starting point for activism is the desire to change current societal norms or beliefs. Activism is defined as “the activity of working to achieve political or social change” (Oxford Dictionary, 2020).

One form of activism is brand activism, defined as “business efforts to promote, impede, or direct social, political, economic, and/or environmental reform […] Brand activism is […] driven by a fundamental concern for the biggest and most urgent problems facing society.” (Kotler & Sarkar, 2018). Examples of businesses that engage in brand activism are Ben & Jerry’s, The Body Shop and Patagonia. Ben & Jerry’s regularly communicates its support for societal changes such as acceptance of the LGBTQIA+ community and rights for refugees and immigrants (Ben & Jerry’s, 2020). The Body Shop promotes animal rights, and fights against testing cosmetics on animals (The Body Shop, 2020). Patagonia is involved in environmental activism, having donated 1% of its sales to environmental initiatives around the world since 1985 (Patagonia, 2020).

In recent years, Airbnb has built a strong reputation for activism. Interestingly, this only started in 2017, when Airbnb started participating in global initiatives aimed at changing societal norms. In Australia, it launched the Until We Belong campaign in collaboration with Qantas. The purpose of the Until We Belong campaign was to increase acceptance for marriage equality in Australia, and make it legal for same-sex couples to get married. Airbnb and Qantas organised a petition and sold – at cost price – an acceptance ring. Airbnb members were asked to wear this ring until Australia made marriage equality lawful (Airbnb, 2017c). This initiative cannot be classified as corporate social responsibility because it is not aligned with pre-existing societal norms. Rather, the Until We Belong campaign proactively fought for a change in societal norms reflected in law. Whether or not this initiative benefitted Airbnb in terms of its image is not clear. If most of its members were in favour of same-sex marriage, it is likely that the Until We Belong campaign strengthened Airbnb’s positive brand image among its Australian members (Hajibaba & Dolnicar, 2018).

In the United States, in 2017, Airbnb expressed disagreement with Donald Trump’s executive order preventing refugees from seven Muslim countries from entering the United States. It activated its Open Homes network to make 3,000 rooms available (Conger, 2017) for stranded refugees and immigrants (Gallagher, 2017). In addition, Airbnb donated USD $1 million raised from its members – along with $800,000 provided directly by Airbnb – to the UN Refugee Agency to assist a further 100,000 refugees in need (The UN Refugee Agency, 2017). Airbnb communicated its position on racial, religious, and sexual equality and immigration by running an advertising campaign at the 2017 Super Bowl (Butler & Judkis, 2017). This initiative was in direct defiance of the order of the President of the Unites States, thus arguably not conforming to societal norms. When Donald Trump expanded his refugee travel ban in 2020 to include six additional countries, Airbnb reiterated its support for refugees and migrants (Airbnb, 2020e).

In January 2019, Airbnb launched another initiative which could be interpreted as disapproval of the actions of United States politicians. During a 35 day government shut down – the longest ever in its history – United States federal executive branch employees went for an extended period without receiving their salaries. In response – for federal executive branch employees who were also hosts – Airbnb offered an extra nights’ payment (in the form of a $110 voucher) for every three nights an employee hosted an Airbnb guest over a three month period (Airbnb, 2019). By boosting this alternative source of income for federal employees, Airbnb expressed support for them in opposition to the President of the United States.

More recently, in the context of the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, Airbnb tweeted its support for the movement and donated USD $500,000 to the Black Lives Matter Foundation (Airbnb, 2020f). Airbnb Design collaborated with Black@Airbnb – a group of Airbnb employees of colour – to create a series of portraits on the theme of the Black Lives Matter movement. The portraits were exhibited at Airbnb offices and on its website (Airbnb Design, 2020). Brian Chesky wrote a long post about his support for the cause, and developed a new policy prohibiting discrimination and committing to being more diverse and having 25% employees of colour on Airbnb’s board and executive team by the end of 2021 (Chesky, 2020). Given that the Black Lives Matter movement advocates for civil disobedience against an unfair systemic issue affecting society, it can be considered as acting in defiance of societal norms. Airbnb’s public support for the movement therefore qualifies as political activism.

Lobbying

Since its inception, Airbnb has engaged in corporate political activity (lobbying). Airbnb’s engagement in lobbying was born out of necessity rather than choice, as it regularly encountered significant regulatory barriers to its operations. In San Francisco, for example, short-term rentals were initially illegal and Airbnb had to depend on political support to sustain its business. It financed Ed Lee’s political campaign for re-election as San Francisco’s mayor (Knight, 2015; Wong, 2015; Roberts, 2016). Lee was re-elected and, shortly thereafter, San Francisco legalised short-term rentals. Deliberately influencing elections in view of organisational benefits represents the most prototypical form of lobbying. In response to what was perceived as inappropriate interference of business entities in elections for their own gain, a law was passed in 2019 that limits the size of contribution a company can make to a political campaign, and the extent of ownership a politician can have in a company (San Francisco Department of Elections, 2019).

Airbnb’s expansion across the United States was accompanied by more regulatory challenges. In 2012, David Hantman was appointed Head of Global Public Policy with his office deliberately located in Washington DC. His role was to convince local governments to legalise short-term rentals (Owen, 2012). Lobbying became an integral component of Airbnb’s strategy. The Shared Cities Network – launched in 2013 – is an example of this strategy (Ferreri & Sanyal, 2018), leading to the adoption of the Shareable Cities Resolution by the US Conference of Mayors (The US Conference of Mayors, 2013). The mayors committed to promoting the sharing economy, to creating a team assessing regulations that may constrain the sharing economy, and to supporting the sharing economy with publicly owned assets. In 2016, Airbnb established a Mayor Advisory Board including former Mayors of Philadelphia, Houston, Adelaide and Rome to push for councils to deregulate short-term accommodation (Salomon, 2016).

In 2014, while busy engaging with councils around the world to shape favourable regulatory frameworks, Airbnb experienced the first instances of damage caused to host properties, igniting a public debate about the safety of short-term accommodation traded via a sharing platform. Airbnb was facing legal challenges around the world (Codwell, 2014; Karni, 2020; Mesh, 2020; O’Brien, 2020; Swan, 2014). To expand lobbying capacity beyond the United States, Airbnb appointed Chris Lehane as Head of Global Policy in 2015. Lehane had strong credentials; as US Government Press Secretary and Special Assistant Counsel he had worked with former Vice President Al Gore and President Bill Clinton (Airbnb, 2020g) – notably during the Lewinsky scandal – and was known as the “master of political hand-to-hand” for his ability to win public relations and political fights (Gay Stolberg, 2004). Airbnb’s lobbying became more public and successful. In 2016, Lehane focused his sights on Japan (Bloomberg, 2016). Tokyo was the fastest growing Airbnb market in 2015, but had in place the most restrictive legislation in the world (von Briel & Dolnicar, 2020; 2021).Within a year of Lehane’s first visit to Japan, short-term rental accommodation regulation was modified, coming into effect in 2018. Tokyo’s regulation remains one of the strictest in the world, but the change in legalisation represented a major victory for Airbnb. For the 2020 Rugby World Cup in Tokyo, Airbnb negotiated exceptionally lenient regulations with local prefectures to provide lodging for visitors. Airbnb was hoping to replicate these exceptions for the 2020 Olympic Games, until their postponement due to COVID-19 (Sugiura, 2019).

Lehane also lobbied for Airbnb in Australia, one of Airbnb’s top ten markets where 30% of the population uses Airbnb (Morgan & Lehane, 2018). Because of the Australian legal system, negotiations took place at state level. First, Lehane persuaded Tasmania to amend its relatively strict regulations to more liberal ones (Grimmer et al., 2019). Next, Lehane worked in New South Wales, where the government established an initial regulatory framework for short-term rentals in 2018. The New South Wales government described the framework as one of the toughest in the world, although an international comparison reveals this not to be the case (von Briel & Dolnicar, 2020). According to Chris Lehane – referring to the hosting limit of 180 days per year imposed on members in Greater Sydney – the “changes will actually help the company” (Morgan & Lehane, 2018). Western Australia, Victoria and Queensland are still in the process of developing regulatory frameworks.

In 2017, Lehane travelled to South Africa and announced a USD $1 million investment for promoting tourism projects in the African continent. This investment came into effect in 2018 and enabled the Africa Travel Summit to take place, bringing together 200 African leaders and representatives from the tourism community. Airbnb also offered hospitality training in 15 townships and set up Airbnb Experiences with a social impact across the Western Cape, notably supporting local and non-profit organisations (Airbnb, 2017d). The following year, South Africa regulated Airbnb activities, handing over all regulatory power to the minister of tourism (Business Tech, 2020). Trading of space on Airbnb increased by between 100% and 200% across all of Africa (Kazeem, 2020).

Another approach to influencing politicians is to engage in strategic collaborative relationships with governments. In 2019, Airbnb fought a lawsuit against the State of New York, which sought to obtain monthly transaction data from online accommodation platforms (von Briel & Dolnicar, 2021). Airbnb won, but voluntarily reached a settlement with the city anyway. A good relationship with the city of New York is beneficial for the company, especially as in 2020 Airbnb announced its intention to be traded on the New York stock exchange. (Carville & Tse, 2020). Chris Lehane commented: “New York is a marathon and not a sprint. We will ultimately get across the finish line” (Rummler, 2019).

Not all of Airbnb’s lobbying activities involve funding politicians and fighting lawsuits. Communication also serves as an effective alternative approach. One Airbnb initiative which uses communication for lobbying is the Airbnb Policy Tool Chest: a website which advises policymakers (Airbnb, 2016d) on possible ways to regulate short-term letting in their areas. Unsurprisingly, regulations beneficial to Airbnb are highly recommended in this tool. Registration systems independent of Airbnb’s online platform are not recommended; they are described as systems involving a “complicated licence or permit”, thus strategically associating registration systems with unnecessary bureaucracy. Airbnb’s tool instead recommends its own online host registration system, which leads to automatic approval upon entering minimal information. This system makes it difficult for local regulators to check compliance with local laws.

Another communication tool that benefits Airbnb is its Home Sharing Clubs network (Airbnb Citizen, 2016). These clubs are advocacy groups for Airbnb composed of hosts and controlled locally “to unite and educate their neighbours and community leaders about the cultural and economic benefits of home sharing”, and to “advocate for fair and clear home sharing regulations in their city”. Chris Lehane explains: “In the Industrial Age, working men and women organized themselves into trade unions, […] as we enter this age of a sharing economy, clubs are the next iteration of people organizing themselves, to represent themselves, advocate for themselves” (Greene, 2018: 207). When Airbnb uses communication as a tool to change regulations and when it activates hosts – in union-like fashion – to demand business benefits from the government, this qualifies as corporate political activity.

Well before COVID-19 devastated the global tourism industry, popular city tourist destinations across Europe had vowed to introduce stricter regulations for short-term rentals. Airbnb reacted by joining forces with other peer-to-peer accommodation platform facilitators at the European level to counteract this development. The number of collaborations between peer-to-peer platform facilitators and governments increased dramatically as a result. Airbnb joined Sharing Economy UK, an industry lobbying association founded in 2015 (Sharing Economy UK, 2020). It also led the creation of the European Collaborative Forum in 2015, uniting businesses operating in the sharing economy sector, including Uber (Lobbyfacts, 2020). The Forum involves yearly round tables between policymakers from the European parliament and 20 leading founders of sharing economy businesses (Green Brodersen, 2016; Murillo, 2020).

The European Commission is currently preparing the Digital Services Act, with the aim of modernising the 2000 e-Commerce Directive which regulates the role and responsibilities of online intermediaries (Chivot & Castro, 2020). When the European Commission expressed a need for local governments to regulate the sharing economy (EU Committee of the Regions, 2015), Nathan Blecharczyk – one of Airbnb’s founders – wrote an open letter to push for increased collaboration with European cities and for a regulator in charge of the totality of the European market (Blecharczyk, 2019). While the final decision is still being negotiated, Airbnb has signed a partnership with other platform facilitators to share anonymised data with the European Commission on a quarterly basis (Airbnb, 2020h). This collaboration marks a change in strategy; in the past Airbnb has been very protective of its data. This partnership is deliberate political action to strengthen Airbnb’s agenda in Europe, with the intention of laws being modified to its benefit – the very definition of lobbying.

Effect on Airbnb members

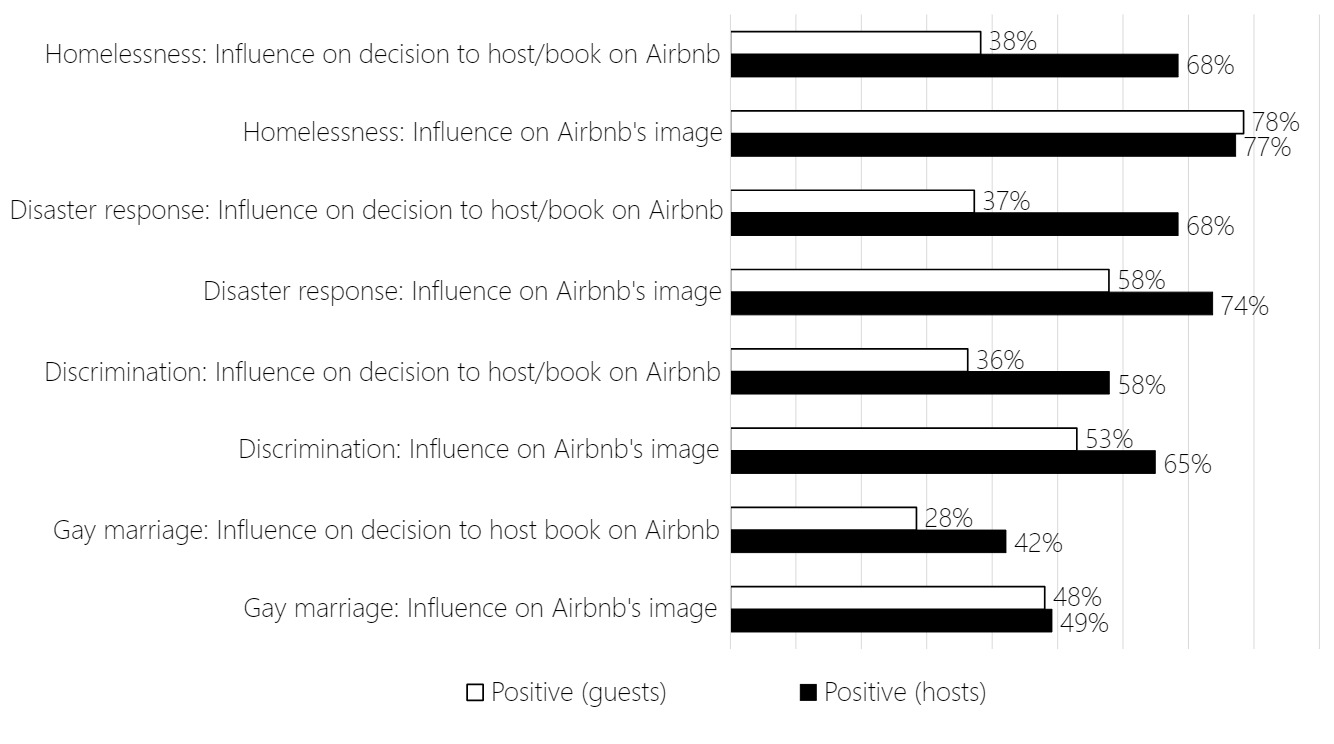

To identify the influence of Airbnb’s activism and corporate social responsibility activities on its members, we surveyed 57 peer-to-peer accommodation hosts and 102 guests. All respondents had booked or listed accommodation through a peer-to-peer accommodation platform in the past 24 months. We asked about Airbnb’s activities in the following areas: gay marriage, racial and religious discrimination, and disaster response and homelessness. Specifically, we asked respondents the following questions: Did you know that Airbnb was lobbying for this cause? Has this knowledge influenced your image of Airbnb? Would this knowledge influence your image of Airbnb? Has this knowledge influenced your decision to host/ book on Airbnb? Would this knowledge influence your decision to host/ book on Airbnb in the future?

Figure 12.1 shows the comparative awareness across Airbnb member groups and causes. As can be seen, a much higher percentage of Airbnb hosts are aware of all these activities than is the case among Airbnb guests. This is not surprising, given that Airbnb actively communicates more regularly with its host community. In terms of the causes, all Airbnb members are more aware of Airbnb’s social responsibility activities than its activism. Between 7% and 8% of guests and between 32% and 42% of hosts are aware of Airbnb’s space donation activities, for example, but only 4% of guests and 14% of hosts know about Airbnb’s political activism in support of legalising gay marriage.

Figure 12.2 shows the percentage of Airbnb hosts and guests indicating that they either were or would be positively influenced by the four causes under study had they known about them. Overall, a higher proportion of hosts are positively influenced by Airbnb’s activities in the area of corporate social responsibility and political activism – with between 49% (gay marriage) and 77% (homelessness) indicating that these initiatives positively influence the image they have of Airbnb. The decision to host on Airbnb has or would positively influence between 42% (gay marriage) and 68% (homelessness and disaster response) of the hosts participating in our survey.

The influence on guests appears to be consistently lower. In terms of the stated influence on the image of Airbnb, between 48% (gay marriage) and 78% (homelessness) report being positively influenced by these activities. When it comes to guest’s decision to book on Airbnb, between 28% (gay marriage) and 38% (homelessness) report that they are or would be positively influenced. While this is a relatively small percentage, it is not negligible. These results, overall, suggest that Airbnb’s activities in the area of political activism and corporate social responsibility do have an effect on its image and on people’s inclination to trade space on its platform.

Evolution

As soon as Airbnb started operating, it was forced to engage in activities not directly related to facilitating the trading of space. Lobbying was a necessity because short-term letting was regulated in different ways across different locations, in many instances preventing Airbnb from operating altogether. Lobbying activities were initially isolated and responsive, attempting to resolve the local issues at hand. As Airbnb grew, lobbying and related activities became strategic and institutionalised, and an integral part of Airbnb’s operations. Over time, Airbnb’s lobbying activity increased.

Airbnb’s corporate social responsibility initiatives commenced much later – nearly ten years after Airbnb was founded. Initially, projects were relatively small, such as the 2016 Signing College Day. Over the years, Airbnb continued to strengthen its corporate social responsibility activities, developing into a supporter of global communities, with the Open Homes initiative one of its flagship projects.

While its lobbying and corporate social responsibility action increased over the years, Airbnb’s political activism does not display the same trajectory. In 2017, Airbnb first publicly communicated its position on polarising societal issues such as refugees and marriage equality. After this initial burst of activity, Airbnb’s political activism action dropped and became virtually non-existent. This raises the question of why Airbnb chose to engage in activism in the first place, and why it stopped engaging, at least temporarily.

Kim Rubey – Airbnb’s Head of Social Impact and Philanthropy – explained that Airbnb’s choice of activism topics emerged naturally from having access to lodging and communities, for example, being able to assist refugee families in finding housing (Fortune Magazine, 2017). Rubey does not explain the reasons driving Airbnb’s support for the LGBTQIA+ community, marriage equality or Black Lives Matter. These causes, however, do align very well with Airbnb’s mission “To live in the world where one day you can feel like you’re home anywhere and not in a home, but truly home, where you belong” (Lat, 2019) and its slogan: “belong anywhere”. Despite Airbnb’s political activism being well-aligned with the nature and positioning of its business, it could be considered risky to voice a position on matters that may not be supported by large parts of its membership base. When Kim Rubey was asked if Airbnb feared repercussions from taking political stands that might not please everyone, she responded: “if [people] don’t believe in the ethos […] for them to make other choices when they travel is absolutely fine with us” (Whiteside, 2018), suggesting that Airbnb was in fact willing to lose both hosts and guests over its convictions and political activism initiatives. Rubey also clarified that the effect of Airbnb’s political activism on business is not measured by Airbnb.

Rubey notes, however, the tangible benefits of Airbnb’s political activism in recruiting the best employees. Topics such as refugee protection, LGBTQIA+ rights and Black Lives Matter are major talking points in the United States. Rubey notes that “employees consistently say that our work to help those in need and the stances we take on policy issues is the number one reason they choose to work at Airbnb” (Whiteside, 2018). In the competitive context of Silicon Valley, where candidates have the choice to work in all-inclusive offices such as Google and Facebook’s headquarters, the political positions Airbnb takes stand out in attracting and retaining the best employees. Rubey’s comments fail to explain why Airbnb’s political activism stopped relatively suddenly. However, the reflections of Airbnb’s founder and CEO post-COVID-19 provide some insight.

COVID-19 emerged at a time when Airbnb had become invisible in terms of political activism. Europe and the United States – the two largest Airbnb markets – became epicentres of the pandemic. Governments around the world imposed historically unprecedented border restrictions, causing Airbnb a loss of USD $1 billion (Crane, 2020). Airbnb was forced to cut 25% of its workforce (Kelly, 2020), and the prospect of hosts moving properties out of the short-term rental market into the safety of the long-term rental market was on the horizon (Dolnicar & Zare, 2020). Experiencing the severe impact of COVID-19 led Airbnb founder and CEO Brian Chesky to rethink the company’s future. Chesky arrived at the conclusion that Airbnb needed to go back to its roots: being at the centre of communities. In an interview with Bloomberg, he said “I think we were a little unfocused and we strayed from our roots […] from connection, belonging and hosting […] I think a year from now people will look at Airbnb and instead of seeing just real estate, they will see hosts. They will say Airbnb is not just a marketplace, Airbnb is a community” (Chang, 2020).

Conclusions

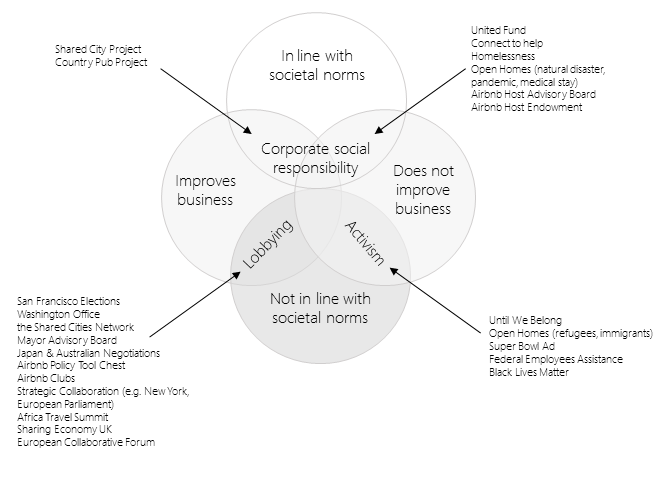

Figure 12.3 graphically illustrates the relationship between the concepts of corporate social responsibility, activism and lobbying, and assigns the entire suite of Airbnb initiatives. As discussed in this chapter, Airbnb participates in corporate social responsibility, but also in large-scale lobbying and activism.

Actions taken by a business that are not linked to its core mission but align with current societal norms and aim at contributing to society are classed as corporate social responsibility. Corporate social responsibility initiatives do not necessarily improve business performance, but they can (Lantos, 2001). Airbnb engages in both types of corporate social responsibility. Activities not improving the business include the worldwide Open Homes program and Airbnb’s contribution to fighting homelessness. Activities improving Airbnb’s business include the Shared City and Country Pub projects.

When a company engages in activities that are beneficial for business but are not in line with current societal norms, this is referred to as lobbying (Mitchell et al., 1997; North, 1990; Lux et al., 2011). Airbnb started lobbying soon after its launch, and Airbnb’s many lobbying activities are diverse in nature and large in scale, targeting entities such as the United States Congress and the European Parliament. Some lobbying activities are visible to the public, such as Airbnb Home Sharing Clubs. Others occur behind closed doors, such as the European Collaborative Forum. Lobbying was necessary for Airbnb to be able to grow its business internationally and to respond to public criticism.

Activism encompasses activities that are not necessarily beneficial for business and are not aligned with current societal norms (Scherer & Palazzo, 2007). Airbnb’s activism has primarily been targeted at societal issues in the United States, including supporting the LGBTQIA+ community, refugees, immigrants, and the Black Lives Matter movement. In contrast with its social responsibility and lobbying efforts, Airbnb’s activism did not commence until 2017, and was re-ignited in 2020 when COVID-19 influenced its strategic direction. Airbnb’s new strategy focuses on community-oriented projects, with a strong commitment to the inclusion of minorities within both the platform and the company’s management.

Airbnb aims to attract and retain members and employees who support its liberal values and is not concerned about losing potential customers who are opposed to those values. Yet, a reassignment of responsibilities ensures that activism activities do not negatively affect Airbnb’s image: five years after being nominated as Head of Communications, Kim Rubey, became Head of Social Impact and Philanthropy. Part of her role includes activism, but her expertise is in politics, communication and lobbying. Similarly, Chris Lehane – who was appointed Head of Policy in 2015 and initiated many lobbying successes for Airbnb – is now Senior Vice President for Global Policy and Communications at the company. This demonstrates the close links between public relations, politics and activism at Airbnb.

Acknowledgements

This chapter is based on Hajibaba, H. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Political Activism, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 255-264.

Survey data collection in 2021 was approved under University of Queensland human ethics application number 2020001659.

References

Airbnb (2016a) Summer search, UNCF and Airbnb come together to celebrate college signing day with first lady Michelle Obama, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/summer-search-uncf-and-airbnb-come-together-to-celebrate-college-signing-day-with-first-lady-michelle-obama

Airbnb (2016b) A new career awaits with Airbnb Connect, aimed at increasing diversity in tech, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/a-new-career-awaits-with-airbnb-connect-aimed-at-increasing-diversity-in-tech

Airbnb (2016c) Airbnb and its community to grant a wish a day in 2017, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-and-its-community-to-grant-a-wish-a-day-in-2017

Airbnb (2016d) Airbnb policy tool chest, retrieved on April 17, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/introducing-the-airbnb-policy-tool-chest

Airbnb (2017a) A new helping hand for our disaster response program, retrieved on July 8, 2020 from http://blog.atairbnb.com/a-new-helping-hand-for-our-disaster-response-program/?_ga=1.146581876.1748974346.1469747770

Airbnb (2017b) Frontline stay global program update, retrieved on July 29, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/frontline-stays-global-program-update

Airbnb (2017c) Until we belong, retrieved on July 8, 2020 from https://untilweallbelong.com/the-acceptance-ring

Airbnb (2017d) Airbnb commits $1 million to boost community-led tourism projects in Africa, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-commits-1-million-to-boost-community-led-tourism-projects-in-africa

Airbnb (2018) Airbnb announces expansion of open homes platform to include medical stays, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-announces-expansion-of-open-homes-platform-to-include-medical-stays

Airbnb (2019) How Airbnb is supporting federal employees impacted by the shutdown, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/anightonus

Airbnb (2020a) Bush fire open home Victoria, retrieved on May 18, 2020 from https://www.airbnb.com.au/openhomes/disaster-relief/victoriabushfires20

Airbnb (2020b) Hosts to help provide housing to 100,000 COVID-19 responders, retrieved on April 22, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-to-help-provide-housing-to-100000-covid-19-responders

Airbnb (2020c) How we’re giving hosts a seat at the table, retrieved on November 12, 2020 from https://www.airbnb.com.au/resources/hosting-homes/a/how-were-giving-hosts-a-seat-at-the-table-283

Airbnb (2020d) The country pub project, retrieved on April 8, 2020 from https://www.airbnb.com.au/d/countrypubproject

Airbnb (2020e) Airbnb responds to expansion of travel ban, retrieved on April 23, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/en-us/airbnb-responds-to-expansion-of-travel-ban

Airbnb (2020f) We stand with #BlackLivesMatter. We are donating a total of $500,000 to the @NAACP and the @Blklivesmatter Foundation in support of their fight for equality and justice, and we’ll be matching employee donations to both groups. Because a world where we all belong takes all of us [Tweet], retrieved on June 28, 2020 from https://twitter.com/airbnb/status/1267536619164151808?lang=en

Airbnb (2020g) Chris Lehane, retrieved on April 17, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/en-au/about-us/leadership/chris-lehane

Airbnb (2020h) Airbnb signs data sharing partnership with European commission, retrieved on April 22, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-signs-data-sharing-partnership-with-european-commission

Airbnb Citizen (2016) Home sharing clubs, retrieved on April 16, 2020 from https://www.airbnbcitizen.com/clubs

Airbnb Design (2020) Visualizing our unity, retrieved on June 28, 2020 from https://airbnb.design/visualizing-our-unity

Ben & Jerry’s (2020) Together we resist, retrieved on October 15, 2020 from https://www.benandjerry.com.au/whats-new/together-we-resist

Blecharczyk, N. (2019) Airbnb responds to EU court decision, retrieved on June 5, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-responds-to-eu-court-decision

Bloomberg (2016) Airbnb’s ‘master of disaster’ comes to Tokyo as regulations loom, retrieved on April 17, 2020 from https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/06/16/business/corporate-business/airbnbs-master-disaster-comes-tokyo-regulations-loom/#.XpkM3G5S-L4

Business Tech (2020) Government to regulate Airbnb in South Africa, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://businesstech.co.za/news/business/311226/government-to-regulate-airbnb-in-south-africa

Butler, B. and Judkis, M. (2017) The five most political Super Bowl commercials, retrieved on April 17, 2020 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/arts-and-entertainment/wp/2017/02/06/the-five-most-political-super-bowl-commercials/?tid=a_inl&utm_term=.5e561f84e486

Cam, D. (2016) Airbnb partners with New York city non-profit to fight homelessness, retrieved on April 22, 2020 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/denizcam/2016/07/01/airbnb-partners-with-new-york-city-nonprofit-to-fight-homelessness/#63bc493131da

Carville, O. and Tse, C. (2020) Airbnb files confidentially for IPO with travel rebounding, retrieved on September 3, 2020 from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/startups/newsbuzz/airbnb-files-confidentially-for-ipo-with-travel-rebounding/articleshow/77647463.cms

Chang, E. (2020) Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky on ‘Bloomberg studio 1.0’, retrieved on November 11, 2020 from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2020-07-10/airbnb-ceo-brian-chesky-on-bloomberg-studio-1-0-video

Chesky, B. (2014) Shared City, retrieved on April 8, 2020 from https://medium.com/@bchesky/shared-city-db9746750a3a

Chesky, B. (2020) An update on the Airbnb anti-discrimination review, retrieved on July 28, 2020 from https://blog.atairbnb.com/an-update-on-the-airbnb-anti-discrimination-review

Chivot, E. and Castro, D. (2020) What the EU should put in the Digital Services Act, retrieved on April 22, 2020 from https://www.datainnovation.org/2020/01/what-the-eu-should-put-in-the-digital-services-act

Codwell, W. (2014) Airbnb’s legal troubles: what are the issues? retrieved on April 17, 2020 from https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2014/jul/08/airbnb-legal-troubles-what-are-the-issues

Conger, K. (2017) Airbnb offers free housing to people stranded by immigration order, retrieved on May 19, 2020 from https://techcrunch.com/2017/01/29/airbnb-free-housing-immigration-ban

Crane, E. (2020) Airbnb’s founder estimates they’ve lost $1 billion during COVID, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8617085/airbnbs-founder-estimates-theyve-lost-1billion-covid.html

Dolnicar, S. and Zare, S. (2020) COVID-19 and Airbnb – Disrupting the Disruptor, Annals of Tourism Research, 102961, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102961

Dolnicar, S. and Zare, S. (2021) Airbnb’s space donation initiatives – before, during and after COVID-19, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

EU Committee of the Regions (2015) Local and regional dimension of the sharing economy, CDR 2698/2015, retrieved on May 2, 2020 from https://cor.europa.eu/en/our-work/Pages/OpinionTimeline.aspx?opId=CDR-2698-2015.aspx?OpinionNumber=CDR%202698/2015

Ferreri, M., and Sanyal, R. (2018) Platform economies and urban planning: Airbnb and regulated deregulation in London, Urban Studies, 55(15), 3353-3368.

Fortune Magazine (2017) These women are disrupting philanthropy, retrieved on April 23, 2020 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3nBcOFyhRyA

Gallagher, L. (2017) President Trump wants to keep them out. Airbnb is inviting them in, retrieved on May 1, 2020 from http://fortune.com/2017/01/29/donald-trump-muslim-ban-airbnb

Gay Stolberg, S. (2004) Clark’s rivals irked by campaign aide’s tactics, retrieved on April 17, 2020 from https://www.nytimes.com/2004/01/16/us/the-2004-campaign-strategy-clark-s-rivals-irked-by-campaign-aide-s-tactics.html

Green Brodersen, S. (2016) Deemly joins the EU Collaborative Economy Forum alongside Airbnb, SnappCar, and Uber, retrieved on November 4, 2020 from https://medium.com/@SaraGreenBrodersen/deemly-joins-the-eu-collaborative-economy-forum-alongside-airbnb-snappcar-and-uber-2a1f0cab7b9e

Greene, L. (2018) Airbnb land, in L. Greene (Ed.) Silicon states: the power and politics of big tech and what it means for our future, Berkeley, California: Counterpoint, 207-213.

Grimmer, L., Vorobjovas-Pinta, O. and Massey, M. (2019) Regulating, then deregulating Airbnb-The unique case of Tasmania (Australia), Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 304-307.

Hajibaba, H. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Political activism, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 255-264, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-36121

Ihnatov, A (2020) Airbnb IPO for hosts. Rental scale-up, retrieved on November 7, 2020 from https://www.rentalscaleup.com/airbnb-ipo-for-hosts-airbnb-host-endowment-and-airbnb-host-advisory-board

Karni, A. (2020) City council blasts Airbnb executives in contentious hearing, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/city-council-blasts-airbnb-executives-contentious-hearing-article-1.2086252

Kazeem, Y. (2020) Africa’s tourism industry can’t get enough of Airbnb, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://qz.com/africa/1388940/airbnb-booming-in-nigeria-ghana-mozambique

Kelly, J. (2020) Airbnb lays off 25% of its employees: CEO Brian Chesky gives a master class in empathy and compassion, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2020/05/06/airbnb-lays-off-25-of-its-employees-ceo-brian-chesky-gives-a-master-class-in-empathy-and-compassion

Kerr, D. (2019) Airbnb gives $2 million to help homeless youth in San Francisco, retrieved on April 22, 2020 from https://www.cnet.com/news/airbnb-gives-2-million-to-help-homeless-youth-san-francisco

Khouri, A. (2019) Airbnb pledges $25 million to support affordable housing and small business, retrieved on April 22, 2020 from https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2019-09-17/airbnb-pledges-25-million-to-support-affordable-housing-and-small-business

Knight, H. (2015) Mayor Ed Lee has knack for raking in big-bucks donations, retrieved on April 28, 2020 from https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Mayor-Ed-Lee-has-knack-for-raking-in-big-bucks-6267454.php

Kotler, P. and Sarkar, C. (2018) The case for brand activism – a discussion with Philip Kotler and Christian Sarkar, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://www.marketingjournal.org/the-case-for-brand-activism-a-discussion-with-philip-kotler-and-christian-sarkar

Lantos, G. P. (2001) The boundaries of strategic corporate social responsibility, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18 (7), 595-632.

Lat, G. (2019) Airbnb mission statement analysis, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://mission-statement.com/airbnb

Lobbyfacts (2020) Goals/remit, retrieved on November 4, 2020 from https://lobbyfacts.eu/representative/13f1e59961c9445db420441e6d0160bd

Lux, S., Crook, T.R. and Woehr, D.J. (2011) Mixing business with politics: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and outcomes of corporate political activity, Journal of Management, 37(1), 223-247.

McWilliams, A. (2015) Corporate social responsibility, in Wiley Encyclopedia of Management, 1-4.

Mesh, A. (2020) City commissioner nick fish berates Airbnb lobbyist, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://www.wweek.com/portland/blog-32614-video-city-commissioner-nick-fish-berates-airbnb-lobbyist.html

Mitchell, N.J., Hansen, W.L. and Jepsen, E.M. (1997) The determinants of domestic and foreign corporate political activity, The Journal of Politics, 59(4), 1096-1113.

Morgan, E. and Lehane, C. (2018) The Business, retrieved on April 20, 2020 from https://search-informit-com-au.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/media;dn=TSM201806070203;res=TVNEWS;type=mp4

Murillo, D. (2020) The politics of the sharing economy, in I. de Luna, À. Fitó-Bertran, J. Lladós-Masllorens and F. Liébana-Cabanillas (Eds.), Sharing Economy and the Impact of Collaborative Consumption, Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 21-36.

North, D.C. (1990) Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance, Oxford: Cambridge University Press.

O’Brien, R. (2020) Hotel industry targets upstart Airbnb in statehouse battles, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://publicintegrity.org/politics/state-politics/hotel-industry-targets-upstart-airbnb-in-statehouse-battles

Owen, (2012) With its latest hire, Airbnb gives a clue on how it’s going to fight rental laws, retrieved on April 17, 2020 from https://www.businessinsider.com.au/airbnb-hires-yahoo-david-hantman-2012-10?r=US&IR=T

Oxford Dictionary (2020) Activism, retrieved on May 1, 2020 from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/activism

Patagonia (2020) The activist company, retrieved on October 15, 2020 from https://www.patagonia.com.au/pages/environmental-grants-and-support

Roberts, C. (2016) Airbnb’s political buyout, retrieved on April 28, 2020 from https://www.sfweekly.com/news/airbnbs-political-buyout

Rummler, O. (2019) New York City is making Airbnb investors nervous pre-IPO, retrieved on April 22, 2020 from https://www.axios.com/airbnb-investors-nervous-ipo-new-york-ef3d2654-3427-4f02-999f-6ac8b0e7fa11.html

Said, C. (2018) Airbnb vows $5 million to fight homelessness in SF, retrieved on April 22, 2020 from https://www.sfchronicle.com/business/article/Airbnb-to-donate-5-million-to-tackle-13385738.php

Salomon, B. (2016) Airbnb hires former mayors to advise, lobby on cities, retrieved on May 6, 2020 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/briansolomon/2016/07/22/airbnb-hires-former-mayors-to-advise-lobby-on-cities/#74f11a41407b

San Francisco Department of Elections (2019) Prohibiting certain campaign contributions, retrieved on January 5, 2021 from https://sfelections.sfgov.org/sites/default/files/20190618_ProhibitingCertainCampaignContributions.pdf

Scherer, A.G. and Palazzo, G. (2007) Toward a political conception of corporate responsibility: Business and society seen from a Habermasian perspective, Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1096-1120.

Sharing Economy UK (2020) About us, retrieved on April 22, 2020 from https://www.sharingeconomyuk.com/about

Starbucks (2020) Starbucks social impact, retrieved on October 15, 2020 from https://www.starbucks.com/responsibility

Stevens, P. (2020) Airbnb announces creation of host advisory board, retrieved on November 12, 2020 from https://shorttermrentalz.com/news/airbnb-host-advisory-board

Sugiura, E. (2019) Airbnb claws its way back in Japan following 2018 listings collapse, retrieved on April 22, 2020 from https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Sharing-Economy/Airbnb-claws-its-way-back-in-Japan-following-2018-listings-collapse

Swan, R. (2014) Protesters accuse Airbnb of desecrating San Francisco’s neighbourhoods, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://www.sfweekly.com/news/protesters-accuse-airbnb-of-desecrating-san-franciscos-neighborhoods

The Body Shop (2020) Forever against animal testing, retrieved on October 15, 2020 from https://www.thebodyshop.com/en-au/about-us/activism/faat/a/a00018

The UN Refugee Agency (2017) Airbnb raises over $1 million for refugees, retrieved on May 19, 2020 from https://www.unrefugees.org/news/airbnbs-belonganywhere-campaign-raises-more-than-1-million-for-refugees

The US Conference of Mayors (2013) In support of policies for shareable cities, retrieved on May 6, 2020 from https://www.usmayors.org/the-conference/resolutions/?category=c10102&meeting=81st%20Annual%20Meeting

von Briel, D. and Dolnicar, S. (2020) The evolution of Airbnb regulation – An international longitudinal investigation 2008–2020, Annals of Tourism Research, 102983, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102983

von Briel, D. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) The evolution of Airbnb’s competitive landscape, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

Whiteside, S. (2018) How Airbnb mixes brand-building and politics, retrieved on April 13, 2020 from https://www.warc.com/newsandopinion/news/how_airbnb_mixes_politics_and_brand_values/40647

WIN (2020) What we do, retrieved on August 3, 2020 from https://winnyc.org/what-we-do

Wong, J. C. (2015) Pro-Airbnb campaign racks up political endorsements, retrieved on April 28, 2020 from https://www.sfweekly.com/news/pro-airbnb-campaign-racks-up-political-endorsements