11 Airbnb and events – before, during and after COVID-19

Sheranne Fairley, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Sarah MacInnes, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Sara Dolnicar, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Please cite as: Fairley, S., MacInnes, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) Airbnb and events – before, during and after COVID-19, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.) Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14204558

The importance of events for destinations

The term event is defined as “anything that happens, especially something important or unusual” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2021). While this definition appears to be rather vague, it is this very vagueness that highlights the substantial heterogeneity in what constitutes an event. At the extreme end is a mega-event, a large global event that is planned many years in advance and has a profound impact on the destination where it takes place, such as the Olympic Games. But only few such events exist, and most destinations are unlikely to ever attract such an event. More common are smaller events, which can include dance, music or sport competitions for children and adults, concerts, food festivals and cultural festivals. While smaller in scale, such events still have substantial potential to benefit the destination. Sporting events involving a series of competitions or games across an entire season, for example, attract fans who follow their teams (Fairley, 2003) – these events have the potential to bring tourism activity to destinations. Arguably, such events may be more advantageous to destinations as they take place in existing infrastructure and bring revenue to the lodging industry (Dermody et al., 2003). In addition, sport events, fairs, exhibitions and conferences also represent excellent reasons for people to attend a destination outside of the peak tourist season (Getz & Page, 2016).

The benefits to destinations are twofold: some are realised immediately and directly, others come to fruition only in the longer-term and are indirect in nature.

Immediate direct benefits include the increase of tourist visitation at the time of the event. Such an increase of tourist visitation is particularly beneficial if it occurs outside of the peak season (Getz et al., 1998; Higham, 1999; Higham & Hinch, 2002). Increased tourist visitation results in heightened tourism revenue through greater visitor spending, and provides opportunities for local businesses to leverage events to their benefit. The most obvious beneficiaries are accommodation providers (Mules, 1988). With demand for accommodation increasing sharply during events, accommodation providers are in the position to charge higher nightly rates. Accommodation providers located close to the event venue are in a particularly favourable position in terms of being able to increase their prices in response to high demand (Herrmann & Herrmann, 2014). Accommodation providers are not the only businesses benefitting from events. Event attendees spend their money on many different things while at the destination: they go out to eat, visit local attractions, go shopping, and use local transport providers. The benefit to the destination is wide, and not limited exclusively to businesses within the tourism sector.

The extent to which an event brings immediate and direct benefits depends on the nature of the event, most critically: the type of event, the number of attendees and the event duration. This explains why some events lead to a measurable increase in hotel revenue and others do not (Depken & Stephenson, 2018; Falk & Vieru, 2020). Events with many attendees are desirable because the additional spending by tourists is multiplied, while longer events are attractive to destinations because tourists spend more money at the destination (Daniels & Norman, 2003). Not surprisingly, therefore, destinations work with event organisers to try to build upon the core event program by offering pre-event and post-event excursions, thus extending the number of days the event contributes to the local economy (Kelly & Fairley, 2018). Finally, the type of event also significantly influences the benefits that destinations can derive because they attract different types of tourists. One striking example for such differences is the comparison between youth sports events and girls’ sport events. The latter have a stronger impact on additional tourist expenditures (Schumacher, 2007), while youth sports events have a stronger effect on the increase of room nights sold (Daniels & Norman, 2003).

Events can also be used to animate destinations and encourage people to visit destinations that they have never considered visiting. One example in the Australian context is Birdsville. A little-known township located at the edge of the Simpson Desert, 1,590 km from Brisbane (the capital of the state of Queensland in Australia), Birdsville is home to 140 people. The annual Birdville Races – first held in 1882 – attracts 9,000 people to Birdsville. A similar number of visitors attend another event held in Birdsville: the Big Red Bash. The Big Red Bash prides itself on being the “the most remote music festival in the world” (Big Red Bash, 2021). The effect these events have had on people’s awareness of the existence of Birdsville is substantial. The Birdville events are also a good example of how events can shape the image of a destination: “The Big Red Bash event is out of control! The location is so unique – it’s just like a lunar scape, with the earth and the sky divided in equal measure. It’s set up cradled in the arms of this amazing 40 metre red sand dune, where the kids can go crazy” (Big Red Bash, 2021). This effect is not unique to Birdsville. The Burning Man Festival is a more globally famous event that takes place in a desert area, attracting some 60,000 people and shaping the perception of deserts as tourist destinations.

Longer-term indirect benefits include awareness-raising for the destination (Veltri et al., 2009), strengthening of destination image (Jago et al., 2003; Kaplanidou & Vogt, 2007) and even the opportunity to reposition a destination in the marketplace, leading to future tourism. There is no doubt that events can be used to position and reposition destinations in terms of their image (Chalip et al., 2003; Green, 2002; Xing & Chalip, 2006; Getz & Fairley, 2004). This is one reason why many destinations seek to embed elements of the destination into media coverage of events – such is the case with events such as the Tour de France and the 2018 Gold Coast Commonwealth Games. To derive maximum destination image benefits, events should be compatible with the desired destination image and part of a larger destination marketing plan (Xing & Chalip, 2006; Chalip, 2017).

It can be concluded that, overall, events increase a destination’s tourism revenues and, in many instances, can contribute significant amounts of money to the destination’s economy. Business events in Brisbane, for example, generate over AUD $257 million in economic impact (Choose Brisbane, 2017). With 70% of event-related expenditure relating to food and accommodation (Marsh, 1984), accommodation providers are among the primary beneficiaries.

Yet hosting events comes with challenges, especially in relation to accommodation, which needs to meet both demand and the requirements of the rights holders of large-scale events. While this does not represent a major challenge when events take place off-season and are relatively small, large events can put substantial pressure on existing infrastructure. This may require the provision of temporary alternative accommodation options or the construction of additional accommodation. To illustrate: 470,000 people attended the London Olympic and Paralympic Games in 2012 (visitbritain, 2013), and one million people the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Rio (CNN, 2014). All of these people required accommodation. If sufficient accommodation cannot be provided, the destination may not be given the opportunity to host an event (Higham, 1999), or potential attendees may choose not to come (Roche et al., 2013). Possible solutions include bringing in – temporarily – facilities that can serve as accommodation. Using cruise ships for this purpose is one approach that has been taken many times in the past, including at the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games, the 2004 Athens Olympic Games and the Super Bowl XXXIX in Jacksonville (Florida). For the latter, five cruise ships added 3,667 rooms to the accommodation offerings, enabling Jacksonville to win the Super Bowl bid. Cruise ships, of course, not only offer beds in rooms, they also add a range of dining and entertainment options for event attendees to enjoy.

Another option to quickly and temporarily increase accommodation capacity is to gain access to existing, unused spaces. This is where the paths of events and peer-to-peer accommodation intersect. Existing spaces were used by event organisers long before Airbnb was launched. The organisers of the 1986 Asian Games, the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games, and the 2002 FIFA World Cup gained access to basic inns (yogwans; Cho, 2004). The organisers of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games – in response to public opposition to spending taxpayer money on constructing new accommodation for the sole purpose of hosting one event – increased the accommodation pool by opening up existing university student dormitories. In 2010, the organisers of the FIFA World Cup set up a network of 10,000 non-traditional accommodation providers in South Africa, including backpacker lodges, guesthouses and bed and breakfasts (TEP, 2006). The Tourism Grading Council of South Africa ensured the suitability of the spaces. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this was the first instance of event attendees staying in accommodation where the owner of the property was present (TEP, 2008). This newly established network contributed 18% of the required accommodation for the event (Swartz, 2008, as reported in Rogerson, 2009). Using existing spaces has several advantages, including reduced pressure on taxpayer funding (Higham, 1999) and improved environmental sustainability by avoiding construction (Veltri et al., 2009).

Airbnb and events before COVID-19

Airbnb has the exact kind of network event organisers need: a global network that – via one single webpage – provides access to millions of spaces around the world. Many of those spaces are underutilised and available for peaks in accommodation demand due to an event. Not surprisingly, therefore, event organisers around the world have formally partnered with Airbnb or informally benefitted from spaces available for booking on Airbnb.com and other peer-to-peer networks.

In 2012, 1,800 London Airbnb hosts earned around USD $4 million by providing accommodation to people who visited London to participate in or watch the 2012 London Olympic Games (Airbnb, 2014). Airbnb was not merely being used as a booking platform. Rather, Airbnb proactively educated hosts and coordinated initiatives with the organisers of this mega-event. This collaborative approach benefitted the Olympic Games, London as a destination, and guests, who were provided with a standard Olympic Games information pack when staying in Airbnb-listed properties.

In 2014, Airbnb hosts in Brazil earned more than USD $38 million by hosting people attending the FIFA World Cup (Airbnb, 2014). Airbnb was a welcome partner for the organisers of the World Cup, providing access to more than 26,000 Airbnb-listed spaces.

Airbnb also teamed up with the 2014 New York City Marathon with the aim of increasing accommodation capacity. This annual event is the largest marathon globally; 53,508 runners completed the route in 2019 (Wikipedia, 2021). About one million people watch the event each year (CNBC, 2014), creating substantial demand for accommodation in the New York City area.

In 2016, Airbnb sponsored the 2016 Rio Olympic Games (US Today, 2015). The Olympic Games benefitted from this by solving accommodation shortages, while Airbnb and its hosts benefitted from direct links on the official Olympic Games websites, noting that they were an officially endorsed accommodation provider.

In 2019, Airbnb entered an agreement with the International Olympic Committee to sponsor the Olympic and Paralympic Games – both the summer and winter editions – until 2028. The deal is reported to be worth USD $500 million (Business Insider, 2019). This deal was in place before the scheduled Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games and will also cover the winter Olympic Games in Beijing (2022) and Milan (2026), as well as the summer Olympic Games in Paris (2024) and Los Angeles (2028). All host cities are noted hotspots for the accommodation provider (Business Insider, 2019). The deal is said to be part of an effort by the International Olympic Committee to assist host cities in reducing the costs associated with the development of hotel infrastructure for the event. However, the sponsorship deal was met with criticism and controversy from stakeholders associated with the 2024 Paris Olympic and Paralympic Games. The Paris mayor made her opposition clear, suggesting she would tighten rules on tourist rentals in Paris, while French hoteliers suggested they would suspend participation in the organisation of the event. This is consistent with recent criticisms of host contracts, which suggest that events rights owners and the contracts they have with suppliers may interfere with a host city’s ability to appropriately leverage an event (Kelly et al., 2019).

The reaction in France is not unique. While Airbnb undoubtedly benefits from collaborating with event organisers, the organisers and destination managers raise a number of concerns, including Airbnb’s lack of commitment to the destination, and financial support. Local and regional tourism marketing organisations are typically funded by the membership fees of local tourism businesses – mostly accommodation providers. To be a member of a local or regional tourism marketing organisation, businesses have to be licensed and insured. As most Airbnb hosts do not comply with these requirements, they cannot become members and, by default, make no contribution to the collective destination marketing efforts. Fairley and Dolnicar (2018) interviewed a few destination marketing managers and event organisers to hear their view. This is what a destination marketing manager had to say:

“We don’t promote businesses or have members … that are not regulated … So if they’re not, if they don’t have public liability insurance, if they’re not seen as a true business then we would actually say, ‘No, you know you can’t be a member.’ … So if they’re doing it correctly then, ‘Yeah, come on board as a member, but if you’re not doing it correctly then sorry, no.” (cited in Fairley & Dolnicar, 2018: 114)

Another concern raised by event organisers and destination marketing managers is that Airbnb is disrupting the established working relationships and collaboration arrangements of the local tourism industry. It carries out cross-promotion activities between event organisers and accommodation providers, for example, making free accommodation available for people involved in events in exchange for being prominently featured as preferred accommodation providers on the webpage, and all other informational materials related to the event (Fairley & Dolnicar, 2018). Another service accommodation providers tend to offer to event organisers is bus transfers for event attendees, to connect the event venue with the accommodation. This is very attractive as it improves the logistics associated with people moving around the destination and is perceived favourably by people who attend the events, making it easier to manage transfers on a daily basis.

Also concerning to event managers is the lack of quality control of properties by peer-to-peer accommodation network facilitators, such as Airbnb (Fairley & Dolnicar, 2018). Ultimately, event managers are concerned about the potential of disappointment with accommodation facilities, especially among VIPs and dignitaries involved with the event.

“We’re a little bit fussy about the accommodation … we make sure the artists have a really good time. We can’t afford for them not to enjoy the experience of where they stay. If we end up having something that’s really not what you really like to be staying in for a couple of days then your experience isn’t as positive as it might be… You just don’t know… You could have a great experience… but there is that quality control thing which is a bit harder.” (cited in Fairley & Dolnicar, 2018: 115)

While some event organisers do point out a number of disadvantages and highlight the strengths of traditional arrangements with licensed commercial tourism accommodation providers, it can be concluded overall that there is a naturally good fit between events and peer-to-peer accommodation. The synergies of organising events and curating an online platform which facilitates the trading of space among ordinary people are obvious. Not surprisingly, therefore, Airbnb has made its collaboration with events a priority. Airbnb issued a report titled Hosting Big Events (Airbnb, 2014), which provided a wide range of examples of mutually beneficial collaborations between Airbnb and event organisers. This report also made a case for the environmental benefits of such collaborations (Juvan et al., 2018) over bringing in or constructing the required accommodation. Airbnb’s interest and willingness to collaborate is not limited to mega-events. Acknowledging the value of smaller events, including seasonal competitions, Airbnb sponsors sporting teams to access their members and fans in an attempt to entice them to join the network as Airbnb hosts. This is one of the most fundamental activities of Airbnb, to ensure long-term success into the future as a multi-sided platform business (Reinhold & Dolnicar, 2021). One example of how Airbnb implements their sports team-based recruitment drives is the North Melbourne (Australian Rules) Football Club. Airbnb has naming rights on the weekly news update page issued by the club, and North Melbourne residents who join as hosts receive cash incentives (Sport Business Insider, 2016).

Airbnb and events during and after COVID-19

On 11 March 2020, when the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic, the event industry was significantly impacted, facing postponements and cancellations of events all around the world (Bok et al., 2020). Events of all scales were affected; local, regional, national, and global events were postponed or cancelled. The event postponement that received the most media attention was the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, which was ultimately rescheduled to take place in 2021. With the large-scale postponement and cancellation of events came the postponement and cancellation of travel plans driven by event attendance, including people who travel to events to actively participate in them, attend as spectators, or to volunteer.

The situation worsened further when Airbnb, on 20 August 2020, announced a global ban on hosting parties or events at Airbnb-listed properties. This ban meant that gatherings of 16 or more were prohibited at Airbnb properties (Airbnb, 2020). The ban is still in place as of January 2021.

On 13 January 2021, Airbnb made an unprecedented event-related decision: it cancelled all existing bookings and blocked the possibility of any new bookings in the Washington DC area during the week of the Presidential Inauguration (Airbnb, 2021). This decision was made in response to the raid on the US Capitol Building in Washington DC on 6 January 2021, which led to the lockdown of the Capitol and five deaths. Airbnb announced that it would provide a full refund and compensate hosts for any money they would have earned for the cancelled reservations. These decisions were made by Airbnb based on calls from local, state, and federal officials asking people to avoid travelling to the DC area for the inauguration. Thus, just as peer-to-peer networks can be used to expand accommodation around events, they can also retract accommodation around events.

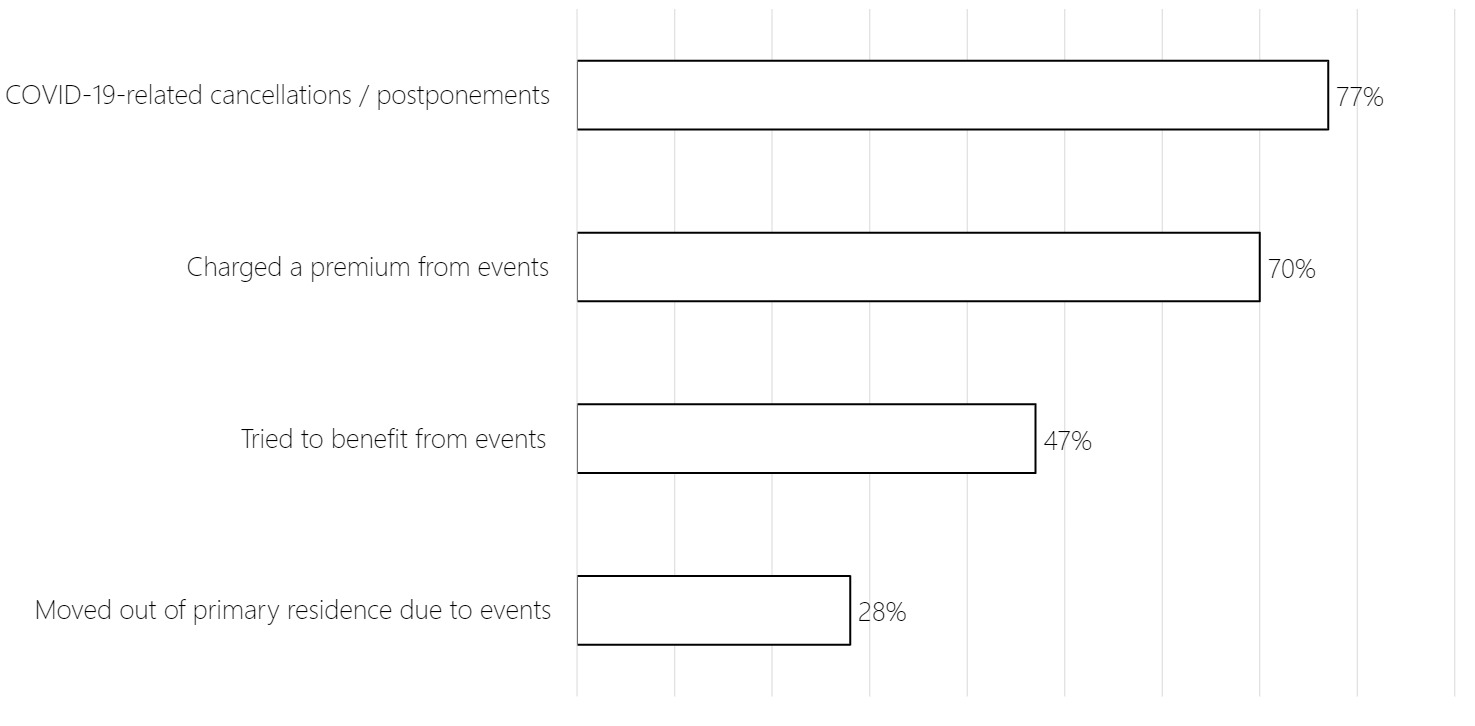

We conducted a survey in January 2021 with 57 Airbnb hosts. Of these, 47% reported they had specifically tried to benefit from local events, 70% of those indicated that they charged a premium in those times, and 67% specifically mentioned the event in their listing. Given these high values and the benefits hosts can gain from events, it is not surprising that 28% reported moving out of their primary residence to take advantage of the high accommodation prices linked to events. However, as anticipated, since COVID-19 77% of hosts reported a negative influence of event cancellations on bookings for their properties. These survey results are summarised in Figure 11.1.

Conclusions

Many destinations host events with the expectation that those events will bring tourism revenue to the destination. However, being able to leverage events to attract tourism revenue first depends on people being able to travel to the event – something that has long been taken for granted but has been most fundamentally challenged in 2020 and 2021 by the movement restrictions put in place by many nations due to COVID-19. Second, the ability to to generate tourism revenue requires sufficient accommodation capacity. In many instances, especially for events that attract a large number of people, providing sufficient accommodation capacity can be challenging. Accommodation capacity can be increased in one of three ways: by constructing new accommodation facilities (an expensive and environmentally unsustainable option), by temporarily bringing in mobile capacity on cruise ships, or by tapping into existing spaces that are not being used when the event takes place. Traditionally, for example, student dormitories can be made available outside of university terms. Peer-to-peer accommodation networks have taken the opportunity to use underutilised space to a whole new level. Facilitators of peer-to-peer accommodation trading websites, such as Airbnb.com, have attracted hundreds of thousands of people to their networks. Their hosts list spare spaces for guests to stay in for short periods of time. Such networks offer an extraordinarily convenient solution for event organisers to meet temporarily increased accommodation demand during an event.

Not surprisingly, therefore, many large-scale events have cooperated with Airbnb, and Airbnb has taken the opportunity to sponsor sports teams to leverage the accommodation needs brought about by seasonal sport competitions. It appears that event organisers have embraced peer-to-peer accommodation, although some concerns remain; Airbnb hosts make no contribution to regional tourism marketing and their properties are not quality-controlled.

Our survey conducted with Airbnb hosts in January 2021 provides empirical evidence of the perceived synergies of organising events and hosting on Airbnb. Almost half of the Airbnb hosts we surveyed made specific efforts to benefit from local events and 77% reported that COVID-19-related event cancellations had a negative effect on their bookings, even if they had not actively tried to benefit from the events. We also surveyed people who use Airbnb to book short-term accommodation. Just over half of these guests (53%) reported booking on Airbnb for an event, and all of them reported never having their booking rejected on this basis. We asked which of the following features of the Airbnb listing were important to them when booking accommodation for an event on Airbnb.com: location of the accommodation close to the event; the event being mentioned on the listing; the listing being themed in line with the event; and having access to the entire property, rather than just one room. Location emerged as the most important factor, with 26% of respondents rating it 100/100 on importance. Access to the entire property was the second most important factor; 21% of respondents ranked it 100/100. The mention of the event in the listing or a themed listing were not viewed as being important: 33% rated the mention of the event in the listing at 0/100, and 28% of respondents rated the theming of the listing at 0/100.

Overall, the conceptual analysis of the synergies of peer-to-peer accommodation and events, the anecdotal evidence of the many formal and informal collaborations between Airbnb and event organisers, and the empirical evidence from our survey studies, suggest that peer-to-peer accommodation in general, and Airbnb as the leading global facilitator of a peer-to-peer accommodation trading platform, will continue to play a key role in catering to the temporarily increase in demand for accommodation around events.

Acknowledgment

This chapter is based on Fairley, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Supporting Events, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 109-119.

Survey data collection in 2021 was approved by the University of Queensland Human Ethics Committee (approval number 2020001659).

References

Airbnb (2014) Hosting big events: How Airbnb helps cities open their doors, retrieved on August 24, 2017 from https://www.airbnbaction.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Airbnb-big-events.pdf

Airbnb (2020) Airbnb announces global party ban, retrieved on 19 January, 2021 from https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-announces-global-party-ban

Airbnb (2021) Airbnb to block and cancel DC reservations during inauguration, retrieved on January 19, 2021 from https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-to-block-and-cancel-d-c-reservations-during-inauguration

Big Red Bash (2021) Birdsville Big Red Bash, retrieved on January 19, 2021 from https://www.bigredbash.com.au/bigredbash/index

Bok, D., Chamari, K. & Foster, C. (2020) The Pitch Invader – COVID-19 Canceled the Game: What can science do for us and what can the pandemic do for science? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 15(7), 917–919.

Business Insider (2019) Airbnb is sponsoring the Olympics until 2028 for a reported $500 million, retrieved on January 1, 2021 from https://www.businessinsider.com/airbnb-wins-reported-500-million-partnership-for-the-2020-tokyo-olympics-2019-11?IR=T#:~:text=Airbnb%20is%20becoming%20a%20worldwide,over%20the%20next%20nine%20years

Cambridge Dictionary (2021) Event, retrieved on January 19, 2021 from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/event

Chalip, L. (2017) Event bidding, legacy, and leverage, in R. Hoye and M.M. Parent (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Sport Management, London: Sage, 401–421.

Chalip, L., Green, B.C. and Hill, B. (2003) Effects of sport event media on destination image and intention to visit, Journal of Sport Management, 17(3), 214–234.

Cho, M. (2004) Assessing accommodation readiness for the 2002 World Cup: The role of Korean-style Inns, Event Management, 8(3), 177–184.

Choose Brisbane (2017) Convention bureau wins to deliver $70 million boost to Brisbane’s economy, retrieved on August 23, 2017 from http://choosebrisbane.com.au/conventions/news/brisbane-convention-bureau-business-events-wins–1617

CNBC (2014) NYC marathon sponsor wants to put you up in a bed, retrieved on August 24, 2017 from https://www.cnbc.com/2014/10/31/new-york-city-marathon-chooses-airbnb-as-a-sponsor.html

CNN (2014) Brazil claims ‘victory’ in World Cup, retrieved on August 24, 2017 from http://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/brazil-world-cup-tourism/index.html

Daniels, M. and Norman, W. (2003) Estimating the economic impacts of seven regular sport tourism events, Journal of Sport Tourism, 8(4), 214–222.

Depken, C.A. and Stephenson, E.F. (2018). Hotel demand before, during, and after sports events: evidence from Charlotte, North Carolina, Economic Inquiry, 56(3), 1764-1776.

Dermody, M.B., Taylor, S.L. and Lomanno, M.V. (2003) The impact of NFL games on lodging industry revenue, Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 14(1), 21–36.

Fairley, S. (2003) In search of relived social experience: Group-based nostalgia sport tourism, Journal of Sport Management, 17(3), 284–304.

Fairley, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Supporting Events, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 109–119, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3608

Falk, M.T. and Vieru, M. (2020) Short-term hotel room price effects of sporting events, Tourism Economics, DOI: 10.1177/1354816620901953

Getz, D. and Fairley, S. (2004) Media management at sport events for destination promotion: Case studies and concepts, Event Management, 8(3), 127–139.

Getz, D. and Page, S. (2016) Progress and prospects for event tourism research, Tourism Management, 52, 593–631.

Getz, D., Anderson, D. and Sheehan, L. (1998) Roles, issues and strategies for convention and visitor bureau in destination planning and product development: A survey of Canadian bureau, Tourism Management, 19(4), 331–340.

Green, B.C. (2002) Marketing the host city: Analyzing exposure generated by a sport event, International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 4(4), 335–354.

Herrmann, R. and Herrmann, O. (2014) Hotel roomrates under the influence of a large event: The Oktoberfest in Munich 2012, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 39, 21–28.

Higham, J. (1999) Commentary–sport as an avenue of tourism development: An analysis of the positive and negative impacts of sport tourism, Current Issues in Tourism, 2(1), 82–90.

Higham, J. and Hinch, T. (2002) Tourism, sport and seasons: The challenges and potential of overcoming seasonality in the sport and tourism sectors, Tourism Management, 23, 175–185.

Jago, L., Chalip, L., Brown, G., Mules, T. and Ali, S. (2003) Building events into destination branding: Insights from experts, Event Management, 8(1), 3–14.

Juvan, E., Hajibaba, H. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Environmental Sustainability, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 265–276, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512–36122

Kaplanidou, K. and Vogt, C. (2007) The interrelationship between sport event and destination image and sport tourists’ behaviors, Journal of Sport & Tourism, 12, 183–206.

Kelly, D.M. and Fairley, S. (2018) What about the event? How do tourism leveraging strategies affect small-scale events? Tourism Management, 64, 335–345.

Kelly, D.M., Fairley, S. and O’Brien, D. (2019) It was never ours: Formalised event hosting rights and leverage, Tourism Management, 73, 123-133.

Marsh, J. (1984) The economic impact of a small city annual sporting event: An initial case study of the Peterborough Church League Atom Hockey Tournament, Recreation Research Review, 11(1), 48–55.

Mules, T. (1998) Taxpayer subsidies for major sporting events, Sport Management Review, 1(1), 25–43.

Reinhold, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) The evolution of Airbnb’s business model, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

Roche, S., Spake, D.F. and Joseph, M. (2013) A model of sporting event tourism as economic development, Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 3(2), 147–157.

Rogerson, C.M. (2009) Mega-events and small enterprise development: The 2010 FIFA World Cup opportunities and challenges, Development Southern Africa, 26(3), 337–352.

Schumacher, D. (2007) The sports event travel market…Getting your share, paper presented at the National Recreation and Parks Association Congress, Baltimore, MA.

Sport Business Insider (2016) North Melbourne books Airbnb partnership, retrieved on August 24, 2017 from http://sportsbusinessinsider.com.au/news/north-melbourne-books-airbnb-partnership

TEP (2006) Quarterly report, year 7 quarter 2, Johannesburg: Tourism Enterprise Programme.

TEP (2008) Towards 2010 and beyond, Johannesburg: Tourism Enterprise Programme.

US Today (2015) Airbnb becomes sponsor of 2016 Olympics in Rio, retrieved on August 24, 2017 from https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/olympics/2015/03/27/airbnb-becomes-sponsor-of–2016-olympics-in-rio/70545576

Veltri, F., Miller, J. and Harris, A. (2009) Club sport national tournament: Economic impact of a small event on a mid-size community, Recreational Sports Journal, 33, 119–128.

VisitBritain (2013) Inbound tourism during the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, retrieved August 24, 2017 from www.visitbritain.org/sites/default/files/vb-corporate/Documents-Library/documents/2013–3%20Inbound%20visitors%20during%20the%20Olympic%20Games.pdf

Wikipedia (2021) New York City Marathon, retrieved on January 19, 2021 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_City_Marathon

Xing, X. and Chalip, L. (2006) Effects of hosting a sport event on destination brand: A test of co-branding and match-up models, Sport Management Review, 9, 49–78.