10 Airbnb catering to the multi-family travel market – before, during and after COVID-19

Samira Zare, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Sara Dolnicar, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Please cite as: Zare, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) Airbnb catering to the multi-family travel market – before, during and after COVID-19, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.) Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland. DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14204555

Multi-family travel before COVID-19

When more than one family travels together, they engage in multi-family travel – irrespective of whether they are relatives or friends. Specific multi-family travel types that are attracted to peer-to-peer accommodation include multi-generational travel (Lago & Poffley, 1993; Kleeman, 2014), family reunion travel (Lago & Poffley, 1993; Yun & Lehto, 2009), and visiting friends and relatives (Jackson, 1990; Backer, 2010; Backer et al., 2017).

Before COVID-19, multi-generational travel – multi-family travel including three or more generations of family members – was increasing in popularity (Kleeman, 2014). This trend is likely to be a consequence of people living longer, people having fewer children, and families not typically living in close proximity to grandparents anymore (Pederson, 1994; Schänzel & Yeoman, 2015). Grandparents also live longer and remain healthier and more mobile for longer. Combined, this leads to grandparents having both the desire and the ability to compensate for the lack of everyday interaction with children and grandchildren by spending vacations together (Lago & Poffley, 1993; Schänzel & Yeoman, 2015). An interesting – and arguably unique – feature of multi-generational travel is the central role of the creation of joint memories, possibly fuelled by the realisation that all family members will not be able to partake in these trips for much longer. The family photo plays a central role in the creation of memories that will outlast the actual holiday experience (Lago & Poffley, 1993). As a consequence of the increasing interest in multi-generational travel, family resorts have experienced increased demand from multiple families spending their vacation together (Brey & Lehto, 2008). The resorts have responded to this trend by adjusting their offerings to better meet the needs of this specific market segment (Brey & Lehto, 2008).

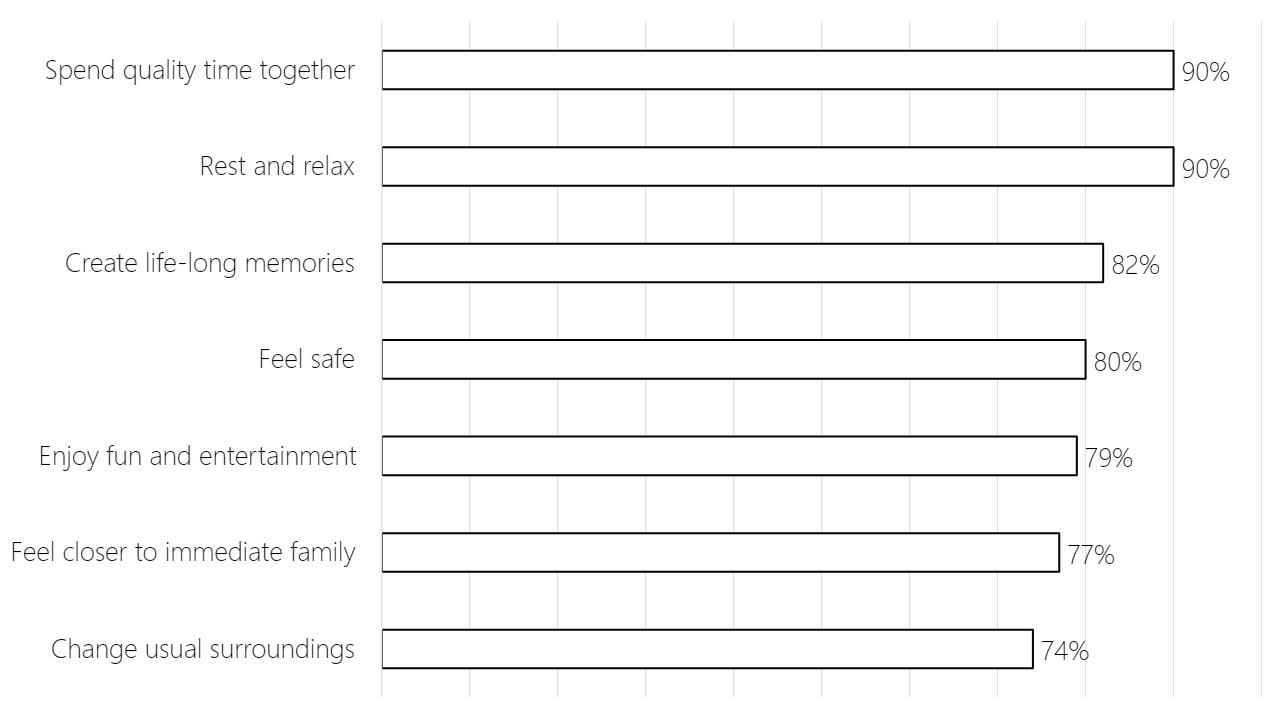

Family reunion travel refers to multi-family units gathering at a destination to meet on a recurring basis (Yun & Lehto, 2009). The number of attendees at such reunions may be low, or it may be as high as 75-100 people. This market is distinctly different from normal multi-family holiday travel because reunion attendees act collectively toward the shared purpose of a reunion rather than pursuing the individual goals typically associated with holidays. Motivations for undertaking family reunion travel include strengthening the connections between family members and ensuring their stability, improving communication among family members, and shaping family structures in terms of the roles specific members play within the broader family structure (Yun & Lehto, 2009). Figure 10.1 shows the main motivations for multi-family travel emerging from an online study conducted in 2017 (Hajibaba & Dolnicar, 2018).

A more common form of multi-family travel is visiting friends and relatives, typically staying with them at their residence (Backer, 2010). Those engaging in visiting friends and relatives travel can be grouped into distinct segments depending on the primary purpose of their trip and their accommodation at the destination (Backer, 2009). Not all travellers who visit friends and relatives stay at their homes (Morrison et al., 2000; Moscardo et al., 2000); some book commercial tourist accommodation, including spaces traded on peer-to-peer accommodation networks. Reasons for booking commercial tourist accommodation include lack of facilities at the traveller’s friend or relative’s home, and travelling with many family members including small children (Backer, 2010).

An interesting aspect of multi-family travel is that people engaging in this form of travel have very specific accommodation needs, which are not well catered to by the main types of tourist accommodation (Schänzel & Yeoman, 2014). The most unique requirement relates to the setup of the space. The optimal setup for multi-family travel is to have multiple bedrooms, multiple bathrooms, a joint common space and a large kitchen (Lago & Poffley, 1993; Airbnb, 2017; Hajibaba & Dolnicar, 2018). According to Airbnb’s own research (2017), most multi-family travellers also expect wireless internet – presumably to cater for a wide range of electronic devices – and about half of them want a pool or spa. When asked to rank accommodation features for a multi-family trip by importance, respondents in Hajibaba and Dolnicar’s (2018) study ranked the number of bedrooms first, followed by the number of beds, the nightly rate, the number of bathrooms, the kitchen and how well equipped it is, air-conditioning, television, wireless internet, parking, pool, washing machine, child safety, gym facilities and children’s toys. These same respondents – when asked which type of tourist accommodation they booked on their most recent multi-family trip – most frequently stayed at higher-end hotels (24%), followed by holiday homes (23%). With this study having been conducted pre-COVID-19, a substantial number of respondents – 16% – also indicated that they went on a cruise ship, and 14% spent their holiday on a campsite. Only 5% indicated that they used Airbnb and another 4% used more traditional bed and breakfast accommodation (Hajibaba & Dolnicar, 2018). Reasons offered by respondents to explain their clear preference for holiday homes include that they represent a cheap option for groups of people, and contain multiple rooms and bathrooms. In terms of Airbnb specifically, people commented on the huge selection of properties to choose from, and on value for money. Those who had no prior experience with Airbnb were reluctant about booking on peer-to-peer accommodation platforms because they were concerned about safety and the trustworthiness of the host, but also about children breaking something in someone else’s house (Hajibaba & Dolnicar, 2018).

Pre-COVID-19 research by Airbnb (2017) revealed that 34% of families travel with grandparents when they go on holiday, and another 20% with friends, illustrating the substantial potential of the multi-family travel market. Further evidence is provided by a TripAdvisor study (2011) – in which 37% of US participants stated their intention to undertake a multi-generational trip in the near future – and a survey conducted by the Preferred Hotel Group (2014), concluding that half of all holidays taken by parents and grandparents involve multiple generations of their family. According to Expedia, around 30% of Australians have been on a multi-generational vacation, fuelling demand for family rooms at hotels (Expedia, 2016). If these statistics can be trusted, multi-family travel may well be one of the main tourism trends of the future.

Multi-family travel during COVID-19

According to an Airbnb report (2020) issued in the midst of the pandemic, family trips with at least one child or infant have increased by 55% in the United States compared to 2019, and many hosts have observed an increase in the size of travel parties including multi-generational family vacationers (Gao, 2020).

After the initial stages of COVID-19 – as the extent of damage to the tourism industry became apparent – destination tourism organisations developed recovery plans targeting domestic travellers, including travellers visiting friends and relatives (Senbeto & Hon, 2020). Previous studies have suggested that the visiting friends and relatives market is resilient because the motivation to travel is independent of external circumstances, making this market segment particularly attractive to destinations in their recovery attempts (Backer & Ritchie, 2017). It is also likely that friends and relatives live in the same country as the travellers; a key advantage during a pandemic characterised by strict border closures put in place by most countries around the world. In addition, in some destinations – including Australia and New Zealand – local community transmission of COVID-19 was low, and most new cases were imported from residents returning to those countries from overseas. Domestic travellers visiting friends and relatives are likely to look for accommodation located in close proximity to their friends and relatives – including peer-to-peer accommodation – and contribute to the local economy by going to cafes, restaurants, wineries and other tourist attractions (Backer & Ritchie, 2017).

Although Airbnb has suffered substantial losses because of COVID-19 – and the associated reduction in bookings and transitioning of rental spaces form the short-term to the long-term market – a few COVID-19-related trends may work in the company’s favour.

During COVID-19, staying isolated from others while travelling has gained importance. Airbnb search engine data shows an increase in requests for entirely independent accommodation such as houses, cottages, cabins, bungalows and villas (Airbnb, 2020a). Airbnb listings in regional and rural areas are expected to increase in popularity among families, especially those travelling with young children and elderly family members. The pull factor of changing scenery – both for children who may have been home-schooled for too long and for the parents who have been working from home for months – creates the desire to break the routine and go away even if it is only a road trip to another house within driving distance. Airbnb and other peer-to-peer accommodation networks offer such opportunities. Airbnb had already detected an upward trend for travelling to regional areas before the pandemic (Volgger et al., 2019). During the pandemic, this trend accelerated, especially among multi-family travellers. Families that had been locked up in their homes for weeks looked for spacious accommodation options with amenities such as pools and playgrounds. Such spaces are more frequently located in regional areas away from city centres (Airbnb, 2020; DuBois, 2020). Airbnb (2020a) also reports that, during the pandemic, families were more frequently than usual choosing listings that permitted pets (22%), provided wireless internet (13%), had kitchens (9%) and offered air-conditioning (8%; Airbnb, 2020a).

The increased emphasis on cleanliness and sanitation during COVID-19 is also valuable to Airbnb in terms of its positioning in the Asian marketplace. Travellers from Asia were increasingly adopting Airbnb before COVID-19 (Volgger et al., 2019). Cleanliness was the single most important factor in choosing accommodation for Chinese and Western travellers (Tsai et al., 2011). Another trend that works to Airbnb’s advantage is the increased price-consciousness of the market. Airbnb has always offered accommodation options with a variety of services suitable for families within any budget range (Lin, 2020). The affordability and diversity of prices are predicted to be even more important to family travellers during and after the pandemic.

To obtain an up-to-date picture of the Airbnb in the context of multi-family travel, we conducted a survey with 102 Airbnb guests in January 2021. First, we asked them whether they had taken a multi-family trip in the past. One third of respondents indicated that they have not, 46% had done so with friends, and 47% had done so with family. These results provide further evidence for the substantial size of this market segment.

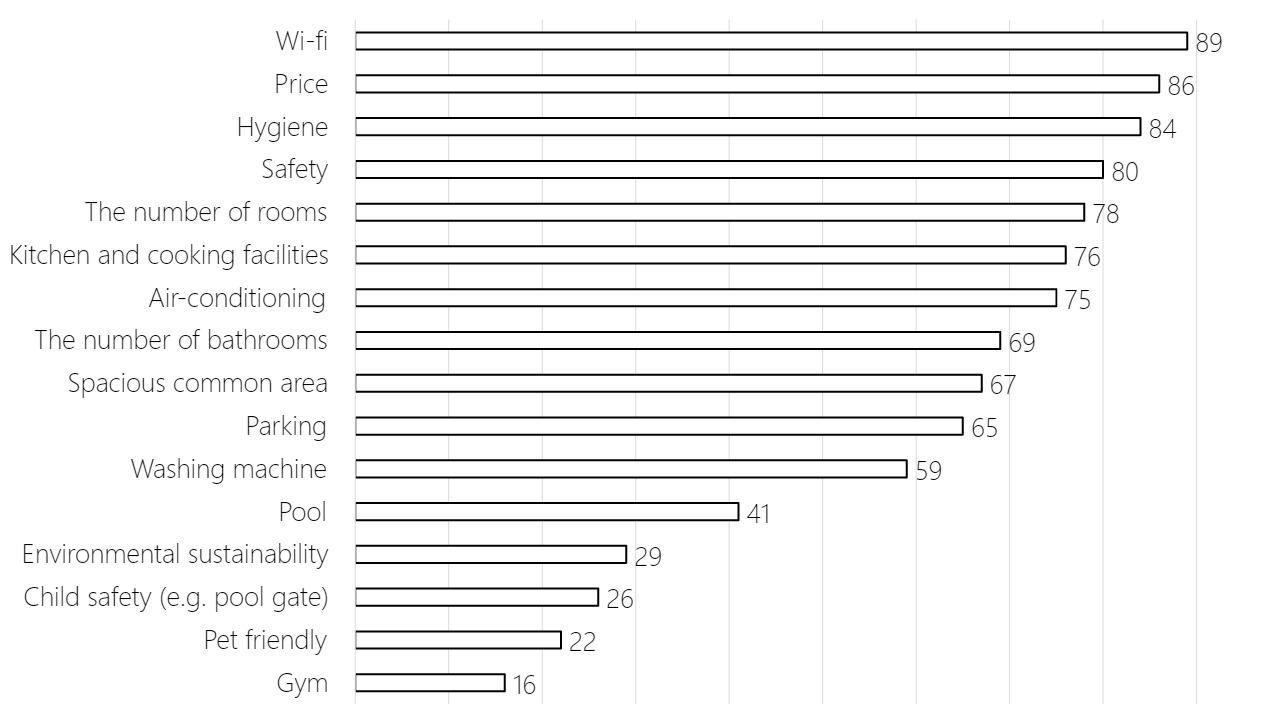

Figure 10.2 shows the responses of those Airbnb guests who indicated that they had been on a multi-family trip to the question of how important a range of accommodation features are to them when they book specifically for a multi-family trip. Wi-Fi, price, hygiene and safety have an average importance value of 80 or more (out of a maximum of 100). The number of rooms, kitchen facilities, and air conditioning are all in the 75 to 78 range, followed by the number of bathrooms, a spacious common area, parking and a washing machine (in the importance range 65 – 69). All other features appear to be important only to a subset of multi-family travellers, including pool (41), environmental sustainability (29), child safety equipment (26), pet friendly (22) and gym (16).

In terms of the effect of COVID-19 on multi-family travel, 44% of survey respondents indicated it will not affect the likelihood of them going on such a trip; 56% believe it will. Of those who believe it will affect the likelihood, only 5% and 3% believe the likelihood of going on multi-family trips with relatives and friends, respectively, will increase. Survey respondents offered the following explanations, most of which related to pandemic-related risks:

“Although barely any of us have had decent exposure in public or haven’t been in contact with the virus directly, we still want to be safe and stay home.”

“Because I would not like to send up in a situation where the border laws change or if people then get infected and we all have to quarantine for an extended period of time.”

“Because many of my relatives have compromised immune system. Therefore, I do not want to expose them to COVID-19, not until most of the population has been vaccinated.”

“Because of the pandemic, I am unable to trust that my friends/family are properly isolating themselves and taking precautions.”

“Covid is so volatile I wouldn’t want to book a massive trip due to cost and not knowing if I can get the money back if the trip is cancelled due to restrictions.”

“Due to covid-19, I prefer not to trip with other families other than my own family.”

“I am worried about others’ safety habits.”

“I don’t feel safe traveling in general at the moment, maybe when most people are vaccinated but until then I won’t.”

“I will not take trips with people outside of my immediate household until Covid is in the rear view mirror.”

“I worry about any possible health risks I may encounter, I don’t want to expose myself and my family to any kind of virus.”

“Reducing contact with as many people as possible is my modus operandi now. Even though they may have been vaccinated, I still think it best to reduce mingling in such close quarters for an extended period of time until vaccine efficiency has been proven in the long-term.”

“This pandemic has changed multi family trips for a certain period of time due to travel restrictions and lockdowns. Now it is very unlikely we can travel with groups as before we did pre covid 19 untill all the restrictions are lifted subject to covid vaccination.”

“With the COVID pandemic money is more tight and with borders closed harder to go on trips.”

Multi-family travel after COVID-19

Some changes to people’s everyday lives during COVID-19 may be retained permanently post-COVID-19 (Miller, 2020), potentially leading to the adaptation of established socio-cultural values and traditions. Tourist behaviour and travel patterns are also likely to change (Wen et al., 2020). The Chinese outbound market, which was hugely important to many destinations around the world, may shrink. By the end of 2020, between 7 and 25 million fewer Chinese departures are expected (Dass & McDermott, 2020). Chinese travellers may choose to travel less during public holidays – such as the Spring Festival – in order to be with their families. Instead, they may prefer to visit their family, friends and relatives during a less busy time at quieter destinations (Wen et al., 2020). Dining out in busy establishments while sharing food and utensils will be limited to small-scale gatherings. Such collectivist values may be re-shaped not only for Chinese tourists, but also for other Asian nations that are a primary source of inbound tourists for many markets.

Slow tourism and smart tourism are projected to rise post-pandemic (Wen et al., 2020). Slow tourism is a contemporary style of travelling in which a longer time is spent at a destination, and the number of destinations visited in a single holiday is lower – quality over quantity. Initial empirical evidence for this trend is provided by a report by AllTheRooms (CNBC, 2020): the average length of stay in Airbnb increased by 18% between January 2020 and June 2020. Smart tourism refers to the use of technology in managing tourists’ expectations and needs. Airbnb can offer multiple benefits by providing affordable prices for families who would like to reunite in a safe environment for an extended period of time, and enabling them to book through technologically advanced processes.

Wellbeing and safety are likely to remain front-of-mind for multi-family travellers post-COVID-19. Travel groups including young children and elderly family members will want reassurance of the hygiene and cleanliness of accommodation before booking. Airbnb’s enhanced cleaning initiative prescribes a standardised cleaning protocol for hosts (Airbnb, 2020b).

Airbnb’s CEO, Brian Chesky, has been shaken by the impact COVID-19 has had on his company (Arlidge, 2020). He has taken the opportunity to reflect on how the uncontrolled growth of Airbnb pre-COVID-19 has shaped the business and its membership, concluding that Airbnb must move back closer to its original roots. Such a reorientation may strengthen its position in the multifamily travel market, which has a long history of booking holiday homes directly from owners using more conventional channels such as classified advertisements. While it is unclear whether – in people’s minds – peer-to-peer accommodation or traditional tourist accommodation will be perceived as the safer accommodation option in future, Airbnb has without doubt an advantage in being able to offer large spaces suitable for multi-family travel in regional and rural – more isolated – areas. These offerings will, no doubt, be attractive to multi-generational travellers, family reunion travellers, and people visiting friends and family.

Acknowledgment

This chapter is based on: Hajibaba, H. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) The Multi-Family Travel Market, in S. Dolnicar, Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 205-214.

Survey data collection in 2021 was approved by the University of Queensland Human Ethics Committee (approval number 2020001659).

References

Airbnb (2017) Have family, will travel: Airbnb finds families prefer travelling to new destinations each year, retrieved on August 11, 2017 from https://press.atairbnb.com/have-family-will-travel-airbnb-finds-families-prefer-travelling-to-new-destinations-each-year

Airbnb (2020a) Pools and pet-friendly homes top Airbnb’s most searched amenities, retrieved on June 29, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/pools-and-pet-friendly-homes-top-airbnbs-most-searched-amenities

Airbnb (2020b) Airbnb’s enhanced cleaning initiative for the future of travel, retrieved on August 26, 2020 from https://www.airbnb.com.au/help/article/2809/what-is-airbnbs-enhanced-cleaning-protocol

Backer, E. (2009) The VFR trilogy, in J. Carlsen, M. Hughes, K. Holmes & R. Jones (Eds.), CAUTHE 2009: See Change: Tourism & Hospitality in a Dynamic World, Fremantle, W.A.: Curtin University of Technology, 1-5.

Backer, E.R. (2010) Opportunities for commercial accommodation in VFR travel, International Journal of Tourism Research,12(4), 334-354.

Backer, E. and Ritchie, B.W. (2017) VFR travel: A viable market for tourism crisis and disaster recovery? International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(4), 400-411.

Backer, E., Leisch, F. and Dolnicar, S. (2017) Visiting friends or relatives? Tourism Management, 60, 56-64.

Brey, E.T. and Lehto, X. (2008) Changing family dynamics: A force of change for the family-resort industry? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(2), 241-248.

CNBC (2020) Rural Airbnb bookings are surging as vacationers look to escape the coronavirus, retrieved on January 6, 2021 from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/08/06/rural-airbnb-bookings-are-surging-as-vacationers-look-to-escape-the-coronavirus.html

Dass, M. and McDermott, H. (2020) Travel & tourism global: potential impact of the coronavirus, retrieved on January 18, 2021 from https://s3.amazonaws.com/tourism-economics/craft/Latest-Research-Docs/Potential-Impact-of-the-Coronavirus.pdf

DuBois, D (2020) Tracking the rebound: New U.S. bookings surpass 2019 levels by 20%, retrieved on August 24, 2020 from https://www.airdna.co/blog/tracking_the_rebound_new_u-s-_bookings_surpass_2019_levels_by_20

Expedia (2016) Travelling tribes: Multi-generational holidays now mainstream, retrieved on September 4, 2017 from https://press.expedia.com.au/travel-trends/ travelling-tribes-multi-generational-holidays-now-mainstream–203

Gao, M. (2020) Rural Airbnb bookings are surging as vacationers look to escape the coronavirus, retrieved on August, 27, 2020 from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/08/06/rural-airbnb-bookings-are-surging-as-vacationers-look-to-escape-the-coronavirus.html

Hajibaba, H. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) The multi-family travel market, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Goodfellow Publishers, Oxford, 205-214, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3616

Jackson, R.T. (1990) VFR tourism: is it underestimated? Journal of Tourism Studies, 1(2), 10-17.

Kleeman, G. (2014) Global tourism update, Geography Bulletin, 46(1), 17-23.

Lago, D. and Poffley, J.K. (1993) The aging population and the hospitality industry in 2010: Important trends and probable services, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 17(1), 29-47.

Lin, P.M. (2020) Is Airbnb a good choice for family travel? Journal of China Tourism Research, 16(1), 140-157.

Miller, J. (2020) Bracing for coronavirus, U.S. residents are changing their behavior, retrieved on August 27, 2020 from https://news.usc.edu/166834/coronavirus-survey-usc-behaviorchanges-health-economic-fallout

Morrison, A., Woods, B., Pearce, P., Moscardo, G. and Sung, H.H. (2000) Marketing to the visiting friends and relatives segment: An international analysis, Journal of Vacation Marketing, 6(2), 102-118.

Moscardo, G., Pearce, P., Morrison, A., Green, D. and O’Leary, J. T. (2000) Developing a typology for understanding visiting friends and relatives markets, Journal of Travel Research,38(3), 251-259.

Pederson, E.B. (1994) Future seniors and the travel industry, Hospitality Review, 12(2), 59-70.

Preferred Hotel Group (2014) Multigenerational travel, retrieved on September 6, 2017 from http://phgcdn.com/pdfs/uploads/B2B/PHG_Multigen_Whitepaper_Final.pdf

Schänzel, H.A. and Yeoman, I. (2014) The future of family tourism, Tourism Recreation Research, 39(3), 343-360.

Schänzel, H.A. and Yeoman, I. (2015) Trends in family tourism, Journal of Tourism Futures, 1(2), 141-147.

Senbeto, D.L. and Hon, A.H. (2020) The impacts of social and economic crises on tourist behaviour and expenditure: an evolutionary approach, Current Issues in Tourism,23(6), 740-755.

TripAdvisor (2011) TripAdvisor survey reveals rise in family travel in 2011, retrieved on September 4, 2017 from http://ir.tripadvisor.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=631471

Tsai, H., Yeung, S. and Yim, P.H. (2011) Hotel selection criteria used by mainland Chinese and foreign individual travelers to Hong Kong, International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 12(3), 252-267.

Volgger, M., Taplin, R. and Pforr, C. (2019) The evolution of ‘Airbnb-tourism’: Demand-side dynamics around international use of peer-to-peer accommodation in Australia, Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 322-337.

Wen, J., Kozak, M., Yang, S. and Liu, F. (2020) COVID-19: potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel, Tourism Review, DOI: 10.1108/TR-03-2020-0110

Yun, J. and Lehto, X.Y. (2009) Motives and patterns of family reunion travel, Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 10(4), 279-300.