6 Resident satisfaction with the growth of Airbnb in Ljubljana – before, during and after COVID-19

Ljubica Knezevic Cvelbar, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

Damjan Vavpotic, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

Sara Dolnicar, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Please cite as: Knezevic Cvelbar, L., Vavpotic, D. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) Resident satisfaction with the growth of Airbnb in Ljubljana – before, during and after COVID-19, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.) Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14195981

Tourism development in Ljubljana

Ljubljana is the capital of Slovenia, a small country located in eastern Central Europe bordering Austria, Hungary, Croatia and Italy. Ljubljana has experienced a significant transformation as a city and tourism destination over the past decade; it developed from being a relatively small, unknown city to an award-winning European city destination, and experienced substantial growth in tourism demand. Ljubljana has always been committed to developing in an environmentally sustainable way (European Commission, 2016). As a possible consequence of this long-term strategy, it was awarded the Green EU Capital Award in 2016 (European Commission, 2016). In the last few years, Ljubljana has been named as one of the top ten most sustainable destinations in the world (Green Destinations, 2020) and has received many awards for tourism development, including: winner of the Sustainable Tourism Award in the European Capital of Smart Tourism 2019 competition (European Capital of Smart Tourism Initiative, 2020); winner of the European Union Cultural Heritage award in 2018 (Europa Nostra, 2018); and winner of the Best of Cities sustainable tourism award at ITB Berlin 2019 (Green Destinations, 2020).

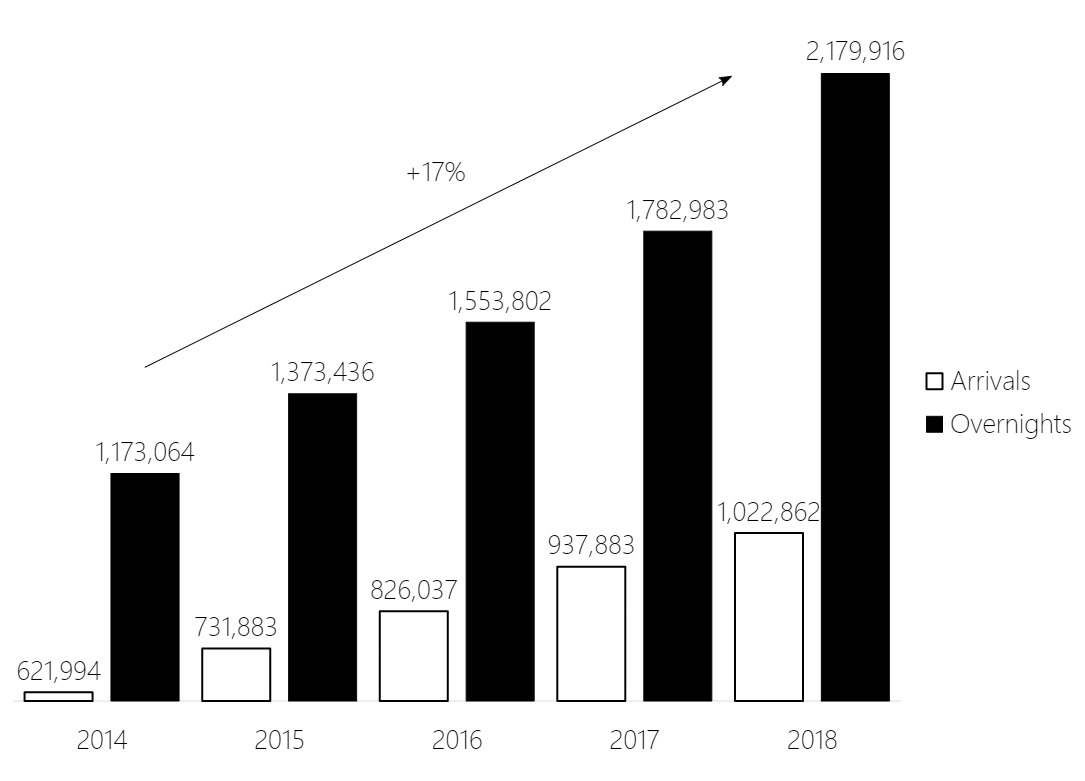

Tourism demand grew significantly in Ljubljana between 2014 and 2018, with an average annual increase of 17% in overnight stays and 13% in arrivals (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2019a). This substantial increase in demand is mostly the result of improved destination management, targeted promotion in international markets, and an overall increase in international tourism demand. In 2014, tourist arrivals to Ljubljana reached 621,994 with 1.17 million overnight stays. In 2018, 1.02 million arrivals led to 2.18 million overnight stays (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2019a, see Figure 6.1) In only four years, the number of tourists in Ljubljana almost doubled.

Traditionally, Ljubljana was a business travel destination, but over the past few years its market share in the leisure market has been increasing, mostly as a consequence of promotional activities positioning Ljubljana as an innovative, lively, vivid, and year-round sustainable destination. Foreign visitors represented some 95% of total overnight stays between 2014 and 2018 (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2019a), with key international source countries being Italy, Germany, the United States, the United Kingdom and Asian countries. Those markets combined account for 36.7% of all overnight stays in Ljubljana (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2019a).

COVID-19 forced tourism in Ljubljana into total hibernation, similar to many other city destinations around the globe. The number of foreign tourists dropped dramatically, and the market structure changed overnight. Current forecasts predict that the number of tourists and overnight stays will drop by 60-70% in 2020 compared to 2019 (Tourism Board Ljubljana, 2020). Any remaining tourism demand after the implementation of travel restrictions was domestic or regional. This created a unique situation never experienced before in Ljubljana’s history, shifting the public debate from how to deal with too many tourists, to how to ensure the tourism industry survives. This chapter investigates residents’ attitudes towards tourism development – in particular the development of peer-to-peer accommodation in Ljubljana with a focus on Airbnb – in the context of the evolution from a pre-pandemic context when demand outstripped accommodation supply, to 2020, a year that has been characterised by empty beds.

The accommodation market in Ljubljana

Historically, the tourism accommodation market in Ljubljana was dominated by hotels, with a market share of 59% of available beds in 2013 (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2014). By 2018 this share had dropped to 54% because the number of private accommodation providers had increased substantially – from 35% in 2013 to 41% in 2017 (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2018). In 2019, Ljubljana had 37 hotels supplying a total of 5,576 beds in 2,774 rooms. Most hotels fall in the four-star category (61%), followed by three-star hotels (30%). Only one hotel in Ljubljana is rated as five-star. Most of the hotels in Ljubljana are not part of a hotel chain; rather, they represent independent, non-branded hotels.

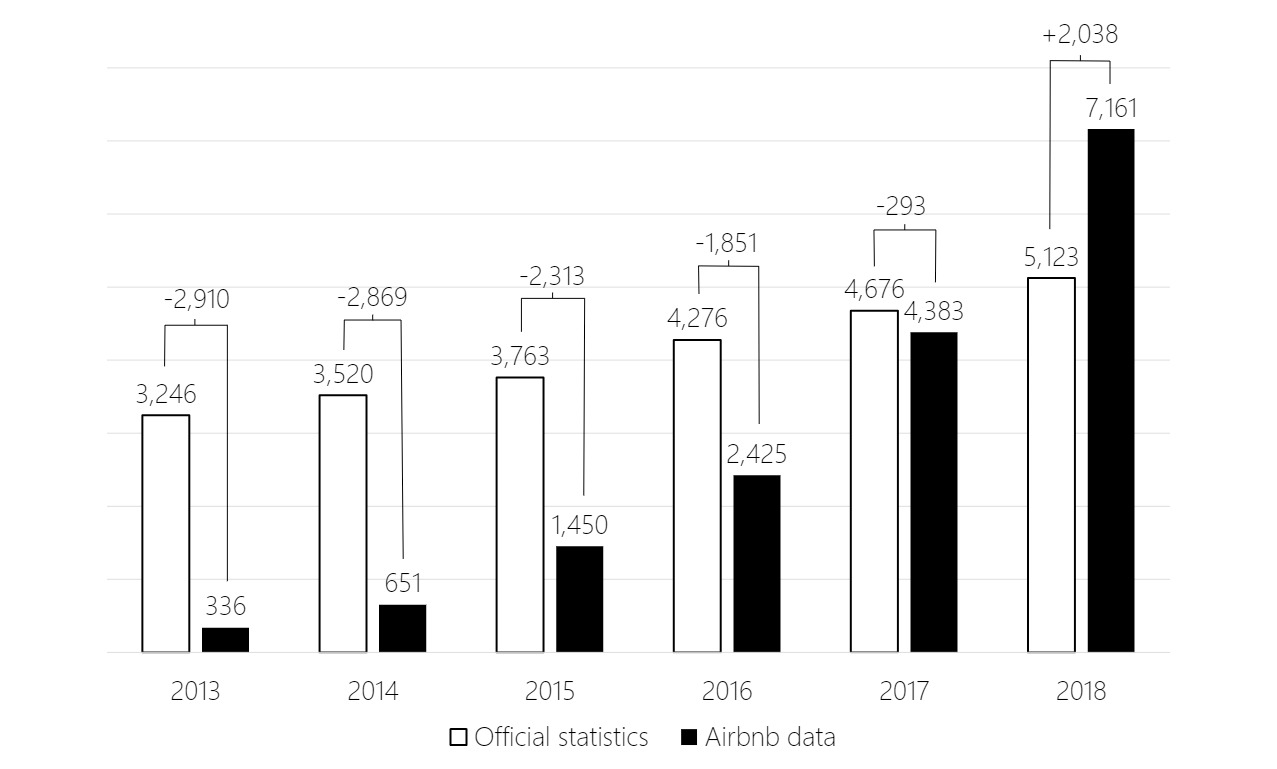

The extensive growth in private accommodation started in 2013, fuelled by local residents seeking to benefit from the opportunity to invest in real estate and repay their mortgages by renting their properties out to tourists on the short-term accommodation market. From 2013 to 2019, locals were able to run such micro-entrepreneurial endeavours very successfully, earning an average of EUR 7,400 in 2019 (AirDNA, 2019), almost double what they could have earned on the long-term rental market. Official statistics failed to capture the additional supply of beds because many locals chose not to declare their short-term rental activities. Figure 6.2 illustrates the high discrepancy between the number of beds in private accommodation reported by the official statistics provided by the Statistical Office of Republic of Slovenia and the number of beds listed on Airbnb according to AirDNA. In 2018, some 2,038 beds on Airbnb were not registered (AirDNA, 2019; Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2019b). There is an even higher discrepancy if we compare data from AirDNA and the Financial Office of the Republic of Slovenia (AirDNA, 2019; Financial Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2019): approximately 80% of the properties rented on Airbnb are not registered and do not pay taxes from their commercial activities.

It appears that there were not many private accommodation properties listed on Airbnb in 2013. Yet, a private accommodation market existed in 2013. The official statistics recorded 3,246 beds in private accommodation in Ljubljana (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2014). AirDNA data suggests that the biggest jump in beds and rooms listed on Airbnb occurred after 2016: the number of beds and rooms offered in Ljubljana on the Airbnb online platform almost tripled between 2016 and 2018 (AirDNA, 2019). Based on AirDNA statistics, the compound annual growth rate of the number of beds between 2013 and 2018 was 84% per annum. This is an unsustainable growth rate over a five-year period, as it burdens the social environment as well as environmental and economic sustainability.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, local media interest increased sharply in 2016 as the public took notice of the rapid expansion of the private tourism accommodation network across the city. A closer inspection of 34 publications in local media outlets suggests that, until 2019, the focus of reporting was the positive developments of tourism in Ljubljana. In 2019, the number of negative media reports relating to tourism development increased substantially (9 out of 33 publications). Public sentiment had shifted. The most discussed aspects include over-crowding in Ljubljana’s city centre, real estate price increases, a shortage of long-term accommodation, price increases in restaurants and bars, and a shortage of parking spaces. Many of these concerns directly relate to the growth in Airbnb listings. The benefits of the increase in tourist accommodation were not as widely discussed. Those benefitting from additional income from hosting were satisfied, while other residents were upset about the negative consequences of the rise of Airbnb in their city.

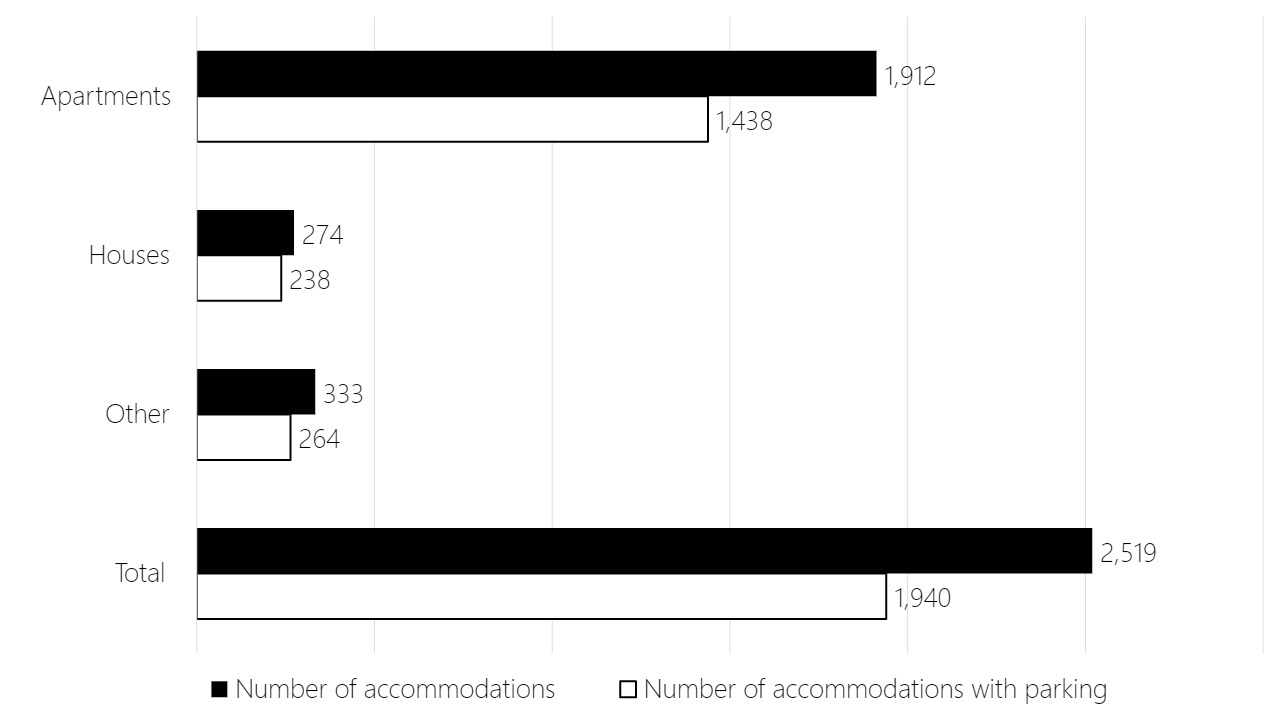

Figure 6.3 illustrates this using parking spaces as an example. As shown, most Airbnb listings in Ljubljana in 2019 were apartments (most of them one or two-bedroom apartments). Two thirds of those apartments included a dedicated parking spot assigned to the apartment.

Ljubljana residents cited the lack of parking and the high price of parking as negative outcomes of tourism. Looking at the data from Airbnb, most apartments listed offered parking. A more detailed inspection reveals that accommodation offerings in Ljubljana listed on Airbnb frequently recommended that tourists use the public parking near the property, placing substantial pressure on public infrastructure and leaving locals without parking spaces in front of their residences. The sudden competition for parking spaces – along with noise complaints and people feeling unsafe in apartment blocks where the neighbours were changing on a regular basis and had no attachment to the building or even the city – caused significant dissatisfaction among residents.

In 2017, the local government became concerned about the expansion of peer-to-peer accommodation in Ljubljana. Short-term and long-term renting activity was regulated at the national level, enabling property owners to rent out their properties unnoticed and without official registration. This is in contrast to most other countries around the world that have faced challenges as a consequence of short-term accommodation being provided to tourists by ordinary residents (von Briel & Dolnicar, 2020). The second problem was taxation. A further problem was rigid real estate legislation that does not allow the inspection of private property without a court order. An association of hotel owners in Ljubljana openly communicated their dissatisfaction, arguing unfair competition. Private property owners were paying substantially lower taxes than hotels (or paying no taxes at all), enabling these short-term accommodation providers to charge lower prices, thus giving them a competitive advantage. The second concern raised by the association of hotel owners was the low quality service provision of private hosts, reflecting poorly on the destination as a whole.

Meanwhile, the structure of peer-to-peer accommodation in Ljubljana was changing – it was developing to become more professional. In 2019, hosts listing more than six properties (offering between 12 and 15 beds in total – a number comparable to a small hotel) represented 36% of Airbnb listings (AirDNA, 2019). Short-term rental micro-entrepreneurship had developed from residents making spare rooms in their houses available for tourists (the Befrienders and Ethicists among hosts, Hardy & Dolnicar, 2018; Fairley et al., 2021) to a business opportunity for Capitalist hosts driven entirely by Airbnb’s revenue-generating potential.

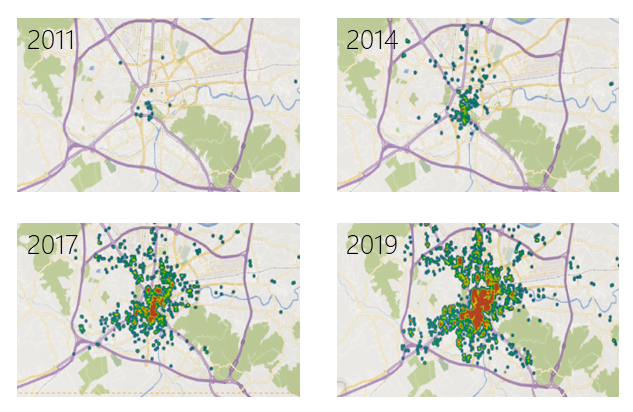

Figure 6.4 illustrates the geographical distribution of properties listed on Airbnb in Ljubljana from 2011 to 2019. The area within the purple boundary line is the city of Ljubljana, with the downtown area located at its centre. Only a few properties were listed on Airbnb in 2011, with a slight increase in 2014. In 2017, supply skyrocketed, spreading in distribution across the entire city area. 2019 was characterised by a very high concentration of listings in the city centre. This was perceived as unsustainable tourism development and local authorities communicated clearly that restrictions would be imposed.

In 2020, shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic, Slovenia was in the process of passing a national law on the regulation of short-term rentals for tourists. The envisaged regulation was strict, and controversial given the proposed requirement for hosts to have the approval of their neighbours before being permitted to offer their property on the short-term rental market (Ministry of Economic Development and Technology, 2019). This requirement would have been among the most restrictive in the world (Hajibaba & Dolnicar, 2019; von Briel & Dolnicar, 2020) surpassed only by the total bans temporarily imposed by some cities. While increased short-term tourist rental activity did negatively affect residents – especially those living in apartment complexes where properties were rented to tourists – introducing legislation that was too restrictive would have also had disadvantages. In a highly restrictive environment, propriety owners may try to avoid registering their properties, instead continuing to rent them out without registration. Monitoring unregistered owners is challenging because inspectors cannot enter a property without the consent of the owner or a court order. These complications open a loophole for delinquent property owners to continue their unregistered business without needing to worry about being penalised.Figure 6.4: Geolocation of Airbnb listings in Ljubljana from 2011 to 2019 (Source: AirDNA, 2019)

Under the proposed regulatory framework (Ministry of Economic Development and Technology, 2020), a maximum number of days per year for renting out properties was put forward – a very common regulatory measure around the world (von Briel & Dolnicar, 2021) In addition, the displaying of registration numbers on the online platform on which the accommodation is listed, such as Airbnb.com, was proposed as a requirement. This is only possible in collaboration with the facilitators of trading platforms and has proven difficult to implement in some cities. In Milan (Italy), for example, property owners are obliged to disclose their registration number on their listing. A random check of 50 listings suggests that many hosts ignore this requirement; more than half of the 50 listings on Airbnb.com did not display a registration number.

While the government was working on legislation, and the Slovenian public was debating the issue of ordinary residents rather than licensed commercial providers letting short-term accommodation to tourists, real estate development projects emerged in Ljubljana. According to an interview with a director of the Tourism Board Ljubljana, entire apartment complexes were built for real estate investors planning to rent out the properties on the short-term market to tourists.

Resident satisfaction before COVID-19

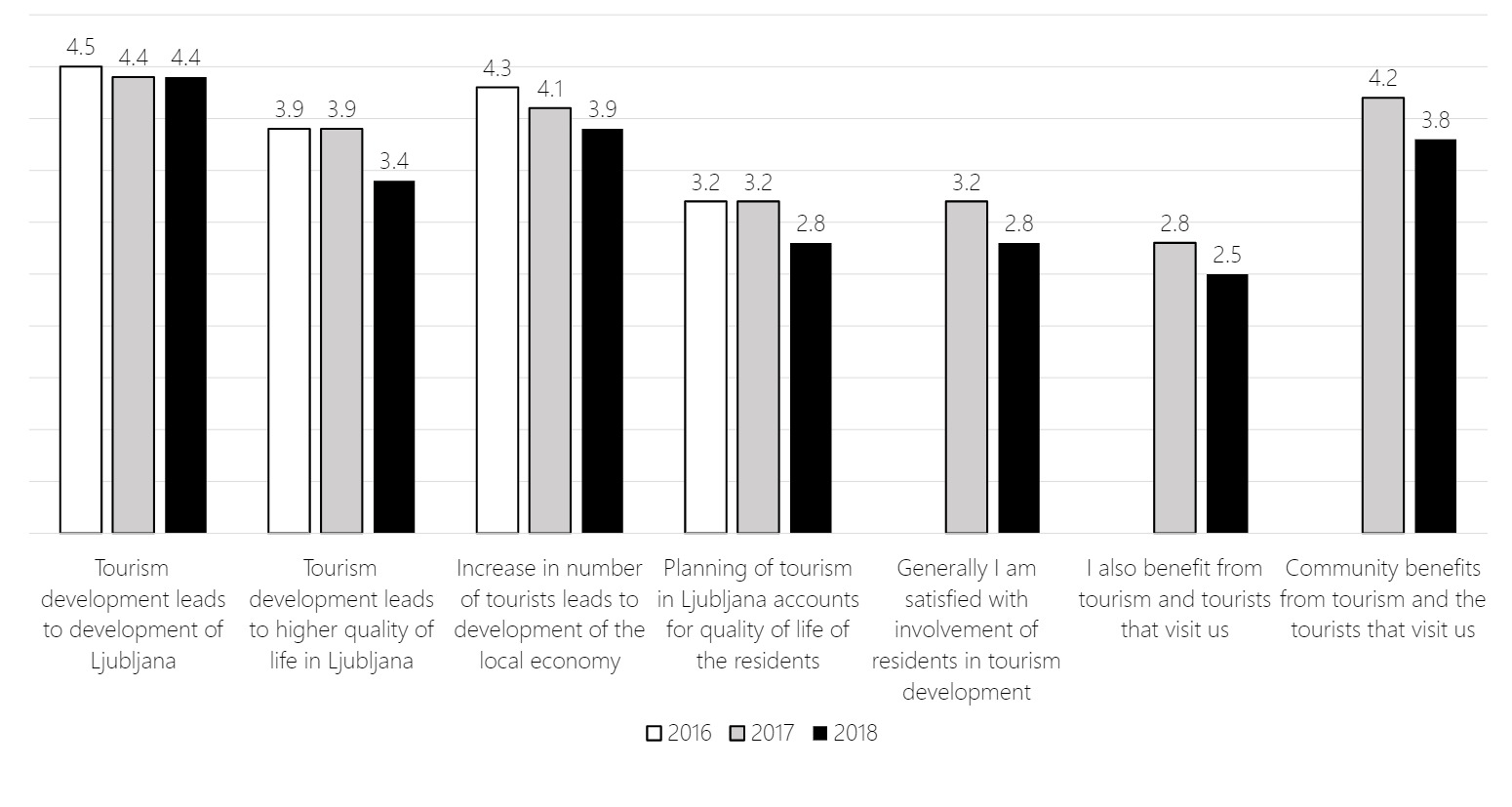

Due to the substantial tourism growth Ljubljana had experienced, Tourism Ljubljana – the city’s destination marketing organisation – was concerned about resident satisfaction with tourism development. From 2016 onward, Tourism Ljubljana regularly measured resident satisfaction with tourism development (Tourism Board Ljubljana, 2016; 2017; 2018). Figure 6.5 shows responses for 2016, 2017 and 2018. The underlying survey study was conducted over these three years only. Overall resident satisfaction with tourism development slightly dropped over the timeframe of the study. Residents expressed dissatisfaction with their involvement in tourism development, and failed to see how the community as a whole or they specifically could benefit from extensive tourism development.

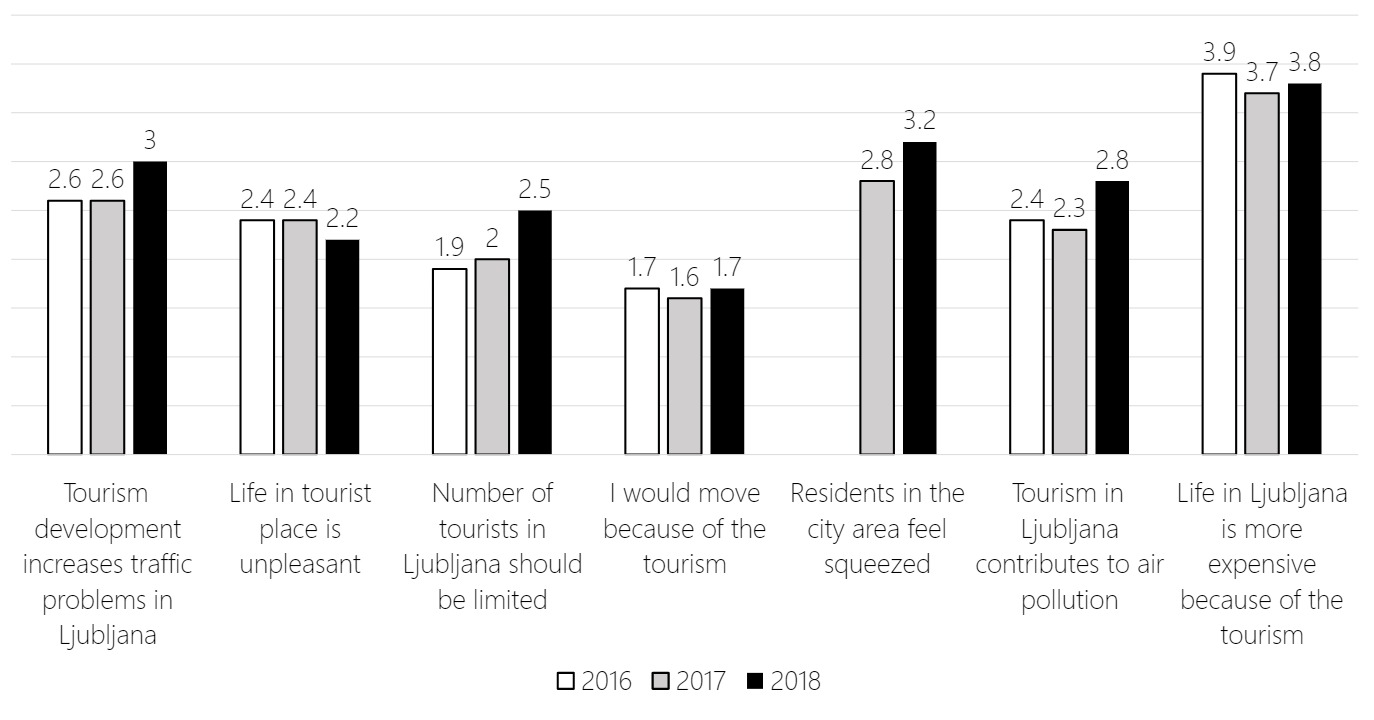

Ljubljana residents were also asked about their perception of the negative impacts tourism development has had on their lives. The main impact residents raised is that life in Ljubljana has become more expensive because of increased tourism activity. Although no explicit question was asked about peer-to-peer accommodation and its impacts on the local community, locals reported rising real estate prices and prices in bars and restaurants as drivers of dissatisfaction (Figure 6.6).

Tourism development and the fast growth of tourist numbers were putting pressure on the local environment. The number of tourists in Ljubljana almost doubled over a five-year period. Existing accommodation capacity was insufficient to cater to this growing demand. Therefore, new approaches to accommodation provision started to evolve, including an increased uptake of peer-to-peer accommodation. Peer-to-peer accommodation offered a quick solution to accommodation shortages (Knezevic Cvelbar & Dolnicar, 2018), but created new challenges for the city. Renting out a spare bed became a lucrative business. Many locals saw an opportunity to earn additional income without much work and without the need for major investment. Government regulation was not keeping up with market development, consequently, income from short-term bed renting was effectively tax free. Interest in the market quickly increased, and many residential areas in the city centre developed into short-term rental hotspots. Soon, the increase in short-term rentals started putting pressure on the long-term rental market, a development experienced by many other popular city tourist destinations around the world (Dolnicar, 2019). Locals were struggling to find long-term rentals to live in as property owners moved from the less lucrative long-term to the more lucrative short-term rental market. Unsurprisingly, this development had a negative impact on resident satisfaction with tourism development, and decreased resident enthusiasm for further tourism growth.

Peer-to-peer accommodation was not the only reason for increased resident dissatisfaction with tourism development. However, it did represent a major trigger. Young families found themselves unable to purchase a house or apartment because of price increases. Students were unable to find long-term rental apartments and could not afford more expensive short-term rental offerings. City centre areas transformed from residential into tourist areas.

The transformation of the city centre did not benefit residents, who found themselves pushed out of the heart of their hometown. This transformation did not benefit tourists either. Tourists enjoy interacting with locals and experiencing a sense of authenticity. With many locals no longer living in the city centre, tourists dominated the streets of Ljubljana, reducing the quality of their vacation experience. Overall, pre-COVID-19, Slovenian regulators reacted too slowly to the challenges posed by peer-to-peer accommodation. The consequences of this regulatory delay were exacerbated by the high demand for peer-to-peer accommodation due, in part, to the limited availability of accommodation in licensed tourist accommodation. Global online peer-to-peer accommodation trading platforms emerge as the primary beneficiaries.

Resident satisfaction during and after COVID-19

COVID-19 severely disrupted the tourism industry in Ljubljana and its development patterns. While the pandemic devastated many local communities who lost key sources of income, employees who lost their jobs, and local authorities who lost an important part of their service export and tax incomes, many have seen COVID-19 as an opportunity to rethink and rebuild tourism. Over the past three decades, tourism development has been fuelled by economic growth, ignoring the limits of the natural and local environment. Growth was desirable and no limits imposed on it. Mass tourism defined tourism in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Ljubljana represents an excellent example of high tourism growth. The number of beds located in Ljubljana and promoted on Airbnb.com grew 84% annually over the five-year period from 2013 to 2018 (AirDNA, 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic suddenly stopped any tourism activity. In the first nine months of 2020, the number of international tourism arrivals in Slovenia was 70% lower than in the same period in 2019 (Slovenian Tourism Board, 2020). Interest in short-term rentals for tourism purposes dropped dramatically.

To determine the stance of property owners who were lucratively generating revenue on the short-term rental market in the three years before COVID-19 hit, we contacted three large real estate agencies in Slovenia and interviewed their owners. Their evaluations of market developments were identical: they reported observing a mass exodus from the short-term rental market into the long-term rental market, as predicted by Dolnicar and Zare (2020). A smaller fraction of owners decided to sell their properties and invest the money elsewhere. Most property owners believe that tourism will bounce back to its pre-COVID-19 development patterns once the pandemic is under control. They also overwhelmingly believe that there will be good opportunities for short-term rentals post-COVID-19 because – in their assessment – tourists will avoid crowds and feel safer in short-term rentals than in established commercial accommodation (which attracts large numbers of tourists to a very limited space). There is some empirical evidence from the summer season of 2020 for this assessment. Owners also believe that leisure travel will resume quicker than business travel after the pandemic, giving short-term rentals a competitive advantage. In general, at least in Ljubljana, property owners are not nervous. They anticipate that the tourism industry will recover, and they plan to return to the short-term rental market. In the meantime, the less lucrative long-term rental market will help them to survive.

Conclusions and implications

In relation to peer-to-peer accommodation and its effects on the local tourism industry and residents, Ljubljana is a particularly interesting case. Historically not a prime tourism destination, Slovenia struggled with increasing tourism arrivals because it lacked sufficient suitable tourist accommodation. At this point, peer-to-peer accommodation was a welcome solution (Knezevic Cvelbar & Dolnicar, 2018); it enabled a rapid increase in accommodation capacity without major infrastructure investment.

Over time, however, Ljubjana started experiencing the same challenges as many other popular city tourist destinations (von Briel & Dolnicar, 2020) as local property owners realised the great revenue potential of the short-term rental market. They pulled out of the long-term rental market – which catered to locals – and started offering their spaces to tourists instead. As the government had not put in place any regulations, locals were effectively pushed out of the city centre and experienced increasing difficulties in finding long-term rental accommodation. Rental prices increased along with property sale prices. Pre-COVID-19, the Slovenian government was in the process of putting regulation in place. COVID-19 disrupted this process as well as tourism activity more generally.

During COVID-19, most property owners reacted to the pandemic by pulling their listings off peer-to-peer accommodation online trading platforms and placing them back on the long-term rental market to secure income during the hibernation of the tourism industry (Dolnicar & Zare, 2020). Some owners chose to sell their properties. In general, however, property owners are optimistic about the future. They believe that tourism will resume post-pandemic, and that short-term rentals in private homes will the preferred option of tourists who will try to avoid accommodation options that are too crowded due to the risk of infection.

Interestingly, the Slovenian government has not leveraged the COVID-19-induced break yet. COVID-19 effectively put a stop to short-term renting in Ljubljana, giving the government time to refine and introduce its short-term rental regulation proposal. It appears that it has not taken this opportunity. Instead, regulators were preoccupied with the management of COVID-19 and its immediate implications for the tourism industry. The risk, post-pandemic, is that history will repeat itself. Property owners may again pull their spaces off the long-term rental market to increase revenues in the more lucrative short-term rental market. Given the ongoing lack of a regulatory framework, it is likely that the residents of Ljubljana will once again experience the negative externalities caused by a flourishing peer-to-peer accommodation sector in their city.

Acknowledgements

This chapter is based on Kneževič Cvelbar, L.K. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Chapter 9 – Filling Infrastructure Gaps, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 98–108.

This research was supported by the Slovenian Research Agency (J5-1783).

References

AirDNA (2019) Property performance monthly data: sample for Slovenia, retrieved on November 17, 2020 from https://www.airdna.co

Dolnicar, S. (2019) A review of research into paid online peer-to-peer accommodation – launching the Annals of Tourism Research curated collection on peer-to-peer accommodation, Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 248-264, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.02.003

Dolnicar, S. and Zare, S. (2020) COVID19 and Airbnb–disrupting the disruptor, Annals of Tourism Research, 102961, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102961

Europa Nostra (2018) Plečnik house – European heritage awards / Europa nostra awards, retrieved on November 17, 2020 from https://www.europeanheritageawards.eu/winners/plecnik-house

European Capital of Smart Tourism (2020) European capital of smart tourism initiative, retrieved on November 17, 2020 from https://smarttourismcapital.eu

European Commission (2016) European green capital, retrieved on November 17, 2020 from https://ec.europa.eu/environment/europeangreencapital/winning-cities/2016-ljubljana

Fairley, S., Babiak, K., MacInnes, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) Hosting and co-hosting on Airbnb – before, during and after COVID-19, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

Financial Office of the Republic of Slovenia (2019) Database on personal income tax on income from renting out property, retrieved on January 1, 2021 from https://www.fu.gov.si/zivljenjski_dogodki_prebivalci/oddajam_sobo_stanovanje_hiso_garazo_v_najem

Green Destinations (2020) Ljubljana – the green destinations collection, retrieved on November 17, 2020 from http://collection.greendestinations.org/dest/ljubljana

Hajibaba, H. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Regulatory reactions around the world, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 120-136, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3609

Hardy, A. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Types of network members, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 170-181, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3613

Kneževič Cvelbar, L.K. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Filling infrastructure gaps, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 98-108, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3607

Ministry of Economic Development and Technology (2019) Hospitality law (zakon o gostinstvu), retrieved on January 12, 2021 from http://www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO393

Ministry of Economic Development and Technology (2020) Podlage za oblikovanje ukrepov v novem Zakonu o gostinstvu glede kratkoročnega oddajanja nastanitev [government publication].

Slovenian Tourism Board (2020) Tourism in numbers, retrieved on January 13, 2021 from https://www.slovenia.info/sl/poslovne-strani/raziskave-in-analize/turizem-v-stevilkah

Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia (2014) Accommodation establishments capacity, tourist arrivals and overnight stays by tourist accommodation establishments, Slovenia, annually, retrieved on September 5, 2020 from https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/-/2164518S.px

Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia (2018) Accommodation establishments capacity, tourist arrivals and overnight stays by tourist accommodation establishments, Slovenia, annually, retrieved on September 5, 2020 from https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/-/2164518S.px

Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia (2019a). Arrivals and overnight stays of domestic and foreign tourists, municipalities, Slovenia, annually, retrieved on September 8, 2020 from https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/-/2164525S.px

Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia (2019b) Accommodation establishments capacity, tourist arrivals and overnight stays by tourist accommodation establishments, Slovenia, annually, retrieved on September 5, 2020 from https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/-/2164518S.px

Tourism Board Ljubljana (2016) Residents satisfaction with tourism development in Ljubljana, Valicon.

Tourism Board Ljubljana (2017) Residents satisfaction with tourism development in Ljubljana, University of Ljubljana.

Tourism Board Ljubljana (2018) Residents satisfaction with tourism development in Ljubljana, Valicon.

Tourism Board Ljubljana (2020) Internal data on tourist arrivals and overnights, Tourism Board Ljubljana.

von Briel, D. and Dolnicar, S. (2020) The evolution of Airbnb regulation – An international longitudinal investigation 2008-2020, Annals of Tourism Research, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102983

von Briel, D. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) The evolution of Airbnb’s regulations, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.