1 Sharing economy, collaborative consumption, peer-to-peer accommodation or trading of space?

Stephan Reinhold, School of Business and Economics, Linnaeus University, Sweden

Sara Dolnicar, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Please cite as: Reinhold, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) Sharing economy, collaborative consumption, peer-to-peer accommodation or trading of space? in S. Dolnicar (Ed.) Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14195945

Is Airbnb part of the sharing economy?

The ability to bring together buyers and sellers via online platforms has fundamentally reshaped many industries, including the tourist accommodation sector. Facilitators of well-developed online platforms, such as Airbnb, managed to give buyers and sellers confidence that trading on such platforms is safe, and offer a range of benefits compared to using traditional intermediaries. These benefits include lower commission rates, a more balanced power relationship between buyer and seller, higher flexibility for sellers, and the potential to find a better match between accommodation features and traveller needs because of the substantial variability of spaces listed on such online platforms (Dolnicar, 2018). Online platforms enabled ordinary people to not only buy, but also sell products and services. The term sharing economy was increasingly used to describe what was essentially a rise in the popularity of platform businesses.

Platform businesses connect buyers and sellers without engaging in direct interaction when buyers and sellers make a transaction. The platform enables sellers to present their product or service, making it visible to buyers. But the terms of the transaction and the decision to go ahead with a specific transaction are up to the buyer and seller (Reinhold & Dolnicar, 2018). Platform businesses existed long before Airbnb, ranging from “dating clubs (men and women), to video game consoles (game developers and users), to payment cards (cardholders and merchants), to operating system software (application developers and users)” (Evans, 2003: 1). The key to their success is attracting and maintaining a substantial pool of different types of customers (Evans, 2003), in the case of Airbnb; people who have available space they can rent out to others for short periods of time (hosts), and people who are in need of short-term accommodation (guests). Sharing is not associated with platform businesses as such.

This is not surprising. Definitions of sharing include to “have or use something at the same time as someone else” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2020), and to “partake of, use, experience, occupy, or enjoy with others” (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2020). Neither of these descriptions reflect the transactions that take place on Airbnb and similar accommodation platforms. Even the most aligned of definitions (to “allow someone to use or enjoy something that one possesses”, The Free Dictionary, 2020) implicitly assumes that the person who possesses the item being shared does so without payment. Allowing guests to use space without paying is not typically the nature of transactions taking place via most platform businesses. Some exceptions exist. Couchsurfing.com, for example, is an online platform that facilitates genuine space sharing without a fee.

Reinhold and Dolnicar (2018) discuss in detail the sharing-exchange continuum proposed by Habibi and colleagues (2016), concluding that – while different platforms populate different positions along this continuum – Airbnb lacks a number of key features associated with sharing, including the non-reciprocal nature of sharing, a joint sense of ownership, the presence of both sharer and recipient, no calculation of value, money not being the motivation for the sharing, and the formation of social connections that live beyond one transaction. The latter can develop on Airbnb, and many interactions on Airbnb do imply at least a minimum social connection between sharing partners. In the detailed paperwork filed for its initial public offering, Airbnb described itself as a global platform (Airbnb, 2020a) and as an enablement platform (Airbnb, 2020a). It refers to hosts sharing access to their homes, talents and passions in the form of listings and experiences. However, there is not a single mention of the sharing economy.

It can be concluded that Airbnb has little to do with the concept of sharing. Airbnb facilitates space “exchanges wrapped in a vocabulary of sharing”, “pseudo-sharing” (Belk, 2014: 7). Hence, the term sharing economy is not suitable to describe Airbnb. On top of these considerations, the sharing economy has neither a consistent, broadly accepted definition (Curtis & Mont, 2020) nor a single business model (e.g., Ritter & Schanz, 2019).

Does Airbnb facilitate collaborative consumption?

Another term that is frequently used in the context of Airbnb is collaborative consumption. It is defined as a “market model that enables individuals to coordinate the acquisition and distribution of a resource for a fee or other compensation (Belk, 2014), where the interaction is at least partially supported or mediated by technology” (Perren & Grauerholz, 2015: 141). Perren and Grauerholz discuss in detail how the concept of collaborative consumption differs from brand communities, collective innovation communities and digital content-sharing communities, but does not explain what makes it different from a multi-sided online platform businesses. The two most fundamental defining characteristics of multi-sided platforms are that “they enable direct interactions between two or more distinct sides” and that each “side is affiliated with the platform” (Hagiu & Wright, 2015: 5), where direct interaction implies that the two sides engaging in the interaction control the terms under which they enter an exchange.

The term collaboration fails to adequately describe the nature of the activity taking place on Airbnb and similar online platforms. To collaborate means to “work jointly with others or together” (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2020), “work with another or others on a joint project” (The Free Dictionary, 2020), or “work with someone else for a special purpose” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2020). Nobody works with another person on Airbnb. The host presents their product on the online platform. The guest purchases or does not purchase the available product. Host and guest do not collaborate on producing or even modifying the accommodation on offer to make it more suitable to the guest or more lucrative to the host. The term collaborative consumption, therefore, is not suitable to describe Airbnb’s peer-to-peer accommodation trading activities.

Is Airbnb enabling the trading of peer-to-peer accommodation?

In our book titled Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries (Dolnicar, 2018) we deliberately chose to use the term peer-to-peer accommodation to avoid the incorrect use of sharing economy and collaborative consumption. In hindsight, we feel this term is also not optimal because it over-emphasises the fact that transactions on online platforms such as Airbnb are made by ordinary people, by peers, as opposed to businesses. In reality, however, Airbnb was always open to commercial accommodation providers, and has increasingly been used by them as a distribution platform.

Strictly speaking, therefore, peer-to-peer accommodation is “space suitable for overnight stays sold by a non-commercial provider (the host) to an end user (the guest) for short-term use through direct interaction between host and guest” (Dolnicar, 2019: 248). Although Airbnb started with an inflatable air mattress in someone’s living room, it has benefitted hugely by allowing licensed, commercial accommodation providers to use the platform as a distribution channel. Commercial providers list properties for no other reason than to maximise their return on investment and profit. While hosts do not need to declare if they are commercial or non-commercial providers, and statistics about the proportion of commercial versus non-commercial properties are not available, there is some empirical evidence for the professionalisation of Airbnb over time (Reinhold & Dolnicar, 2021). In 2017, for example, two thirds of Airbnb listings were entire homes and only one third were private rooms in someone’s home – a substantial shift from 2012 when entire homes accounted for only 57% of listings (Ke, 2017). It is likely that the proportion of private room listings was much higher still in 2008 when Airbnb was founded. Furthermore, in 2017, one third of listings were “owned by 9.4% of hosts, each of whom has at least three listings, and one host even owns 1,800 listings” (Ke, 2017: 132).

The desire to increase revenue was not the only factor that led to Airbnb’s transition from a platform building trust between people in order to make them comfortable letting each other stay at their homes or holiday homes, to an online trading platform for short-term rentals. Pressure to reduce the potential for discrimination (Hajibaba & Dolnicar, 2018) led to modifications of the Airbnb online platform, which significantly altered the Airbnb space trading experience. For example, a guest’s picture is no longer displayed until a booking is confirmed. Removing the picture removes much of the social connection people experienced when booking on Airbnb. The introduction and wide adoption by hosts of Instantbook is another development that led to a substantially reduced need for direct interaction between host and guest. If the space is vacant it can be booked, without any questions asked and without a conversation ahead of the booking. Airbnb has developed from a platform connecting humans to an online trading platform providing access to short-term accommodation and tourist experiences (Gardiner & Dolnicar, 2018; 2021).

To complicate things further, the success of Airbnb has created a large number of other businesses that support hosts (Sigala & Dolnicar, 2018; Fairley et al., 2021), including hosting agents. Hosting agents (Airbnb, 2020b) can handle all aspects of hosting, including interacting with guests, responding to guest enquiries, maintaining and cleaning the property, changing towels and linen, organising key handovers, optimising the price, and offering 24/7 support to guests. When a host engages a hosting agent, no further direct interaction occurs between the host and the guest. The host is effectively a property investor, and the hosting agent is equivalent to a business with management rights. This model is very common in tourism: individuals own units in resort complexes, which are then managed by hotel groups or individuals who purchase the management rights.

It can be concluded that, while correctly capturing the original Airbnb model and its ethos, the term peer-to-peer accommodation platform facilitator is no longer an accurate descriptor for Airbnb as it is today, nor for other, similar businesses that facilitate the online trading of space.

What do Airbnb hosts and guests think?

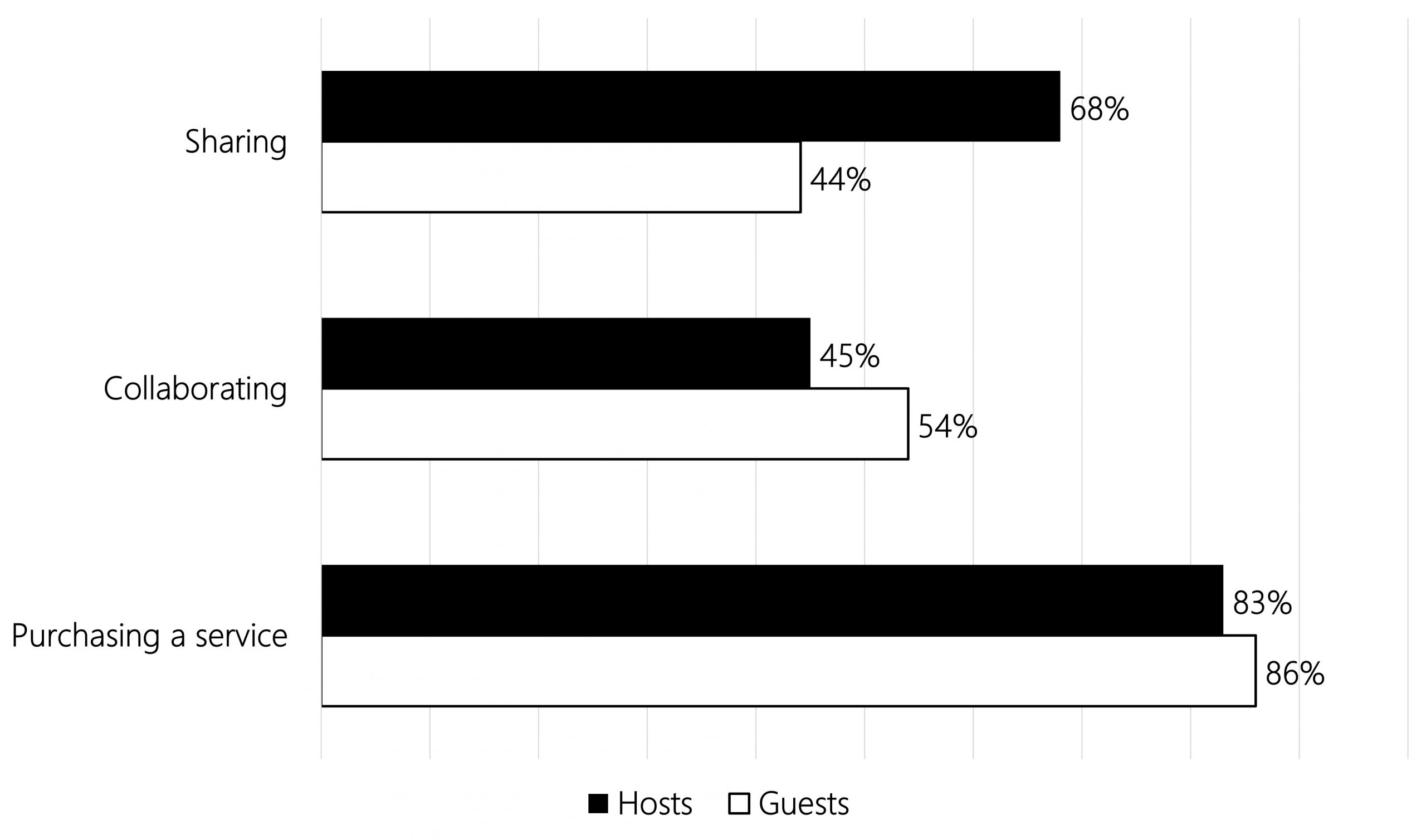

In January 2021 we conducted an online survey with 102 Airbnb guests and 47 Airbnb hosts located in Australia, the US, New Zealand, Canada and the UK. We asked them whether they perceived, when they were booking accommodation on Airbnb, that they were engaging in sharing with the Airbnb host, that they were collaborating with the Airbnb host, or that they were purchasing a service from the Airbnb host. Figure 1.1 shows the results.

What term should we use when referring to Airbnb?

With sharing economy, collaborative consumption and peer-to-peer accommodation deemed unsuitable to describe Airbnb, what term can we use to accurately describe it? Is the less catchy, less romantic, rather long and clumsy term multi-platform business that facilitates the trading of space the best one to use in order to avoid any misleading connotations? We argue that this is indeed the case, and that it was the case before COVID-19, during COVID-19 and will probably remain so long after COVID-19, even if Airbnb redirects its positioning back toward its roots of serving communities. Finally, it is also consistent with Airbnb’s self-identification as a global enablement platform.

Acknowledgements

This chapter is based on: Reinhold, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) The Sharing Economy, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 15-26.

Survey data collection in 2021 was approved by the University of Queensland Human Ethics Committee (approval number 2020001659).

References

Airbnb (2020a). Airbnb, Inc. – Form S-1 registration statement under the securities act of 1933, retrieved on February 10, 2021 from https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1559720/000119312520294801/d81668ds1.htm”>000119312520294801/d81668ds1.htm

Airbnb (2020b) Hosting handled for you, retrieved on August 19, 2020 from https://www.airbnb.com.au/d/hosting-services

Belk, R. (2014) Sharing versus pseudo-sharing in Web 2.0, The Anthropologist, 18(1), 7-23, DOI: 10.1080/09720073.2014.11891518

Cambridge Dictionary (2020) Collaborate, retrieved on August 19, 2020 from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/collaborate

Cambridge Dictionary (2020) Sharing, retrieved on August 19, 2020 from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/sharing

Curtis, S.K. and Mont, O. (2020) Sharing economy business models for sustainability, Journal of Cleaner Production, 266, 121519, DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121519

Dolnicar, S. (2018) Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3454

Dolnicar, S. (2019) A review of research into paid online peer-to-peer accommodation: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research curated collection on peer-to-peer accommodation, Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 248-264, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.02.003

Evans, D.S. (2003) Some empirical aspects of multi-sided platform industries, Review of Network Economics, 2(3), 191-209.

Fairley, S., Babiak, K., MacInnes, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) Hosting and co-hosting on Airbnb – before, during and after COVID-19, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

Gardiner, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Networks Becoming one-stop travel shops, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 87-97, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512–3606

Gardiner, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) Airbnb’s offerings beyond space, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

Habibi, M.R., Kim, A. and Laroche, M. (2016) From sharing to exchange: An extended framework of dual modes of collaborative nonownership consumption, Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 1(2), 277-294.

Hagiu, A. and Wright, J. (2015) Multi-sided platforms, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 43, 162-174.

Hajibaba, H. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Do Hosts Discriminate? in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 215-224, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3617

Ke, Q. (2017) Sharing means renting? An entire-marketplace analysis of Airbnb, Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Web Science Conference, 131–139.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2020) Collaborate, retrieved on August 19, 2020 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/collaborate

Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2020) Share, retrieved on August 19, 2020 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/share

Perren, R. and Grauerholz, L. (2015) Collaborative consumption, International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 4, 139-144.

Reinhold, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) The sharing economy, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 15-26, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3600

Reinhold, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) The evolution of Airbnb’s business model, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

Ritter, M. and Schanz, H. (2019) The sharing economy: A comprehensive business model framework, Journal of Cleaner Production, 213, 320-331, DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.154

Sigala, M. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Entrepreneurship opportunities, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 77-86, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3605

The Free Dictionary (2020) Collaborate, retrieved on August 19, 2020 from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/collaborate

The Free Dictionary (2020) Sharing, retrieved on August 19, 2020 from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/sharing