2 The evolution of Airbnb’s business model

Stephan Reinhold, School of Business and Economics, Linnaeus University, Sweden

Sara Dolnicar, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Please cite as: Reinhold, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) The evolution of Airbnb’s business model, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.) Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14195957

The academic fascination with Airbnb, but not with its business model

By reinventing home stays and tourism experiences, Airbnb has introduced to the tourism and hospitality sectors one of the most fascinating innovations of the past decade. By facilitating an online peer-to-peer trading platform, Airbnb has extended short-term accommodation capacity in unprecedented ways (Dolnicar, 2019), and provoked strong responses from both the established commercial tourism accommodation sector (Zach et al., 2020) and local regulators (von Briel & Dolnicar, 2020).

Airbnb has adapted the platform business model to the long tail of hospitality in ways that had not been attractive to established distribution networks (Reinhold et al., 2020). In so doing, Airbnb demonstrated that a Silicon Valley-style start-up company (Gallagher, 2017) can scale in tourism and hospitality, and create a broad ecosystem that facilitates new entrepreneurial activity serving at a number of levels: hosts, and providers assisting hosts with service provision (e.g., Sibbritt et al., 2019; Sigala & Dolnicar, 2018). While these additional entrepreneurial opportunities were welcomed, the success of Airbnb also presented host communities and other stakeholders with new sets of problems (e.g., Xie et al., 2020). For both its merit and associated conflict, Airbnb has become an iconic, category-defining case study in industry and scholarly discourse (Dolnicar, 2019; Kuhzady et al., 2020).

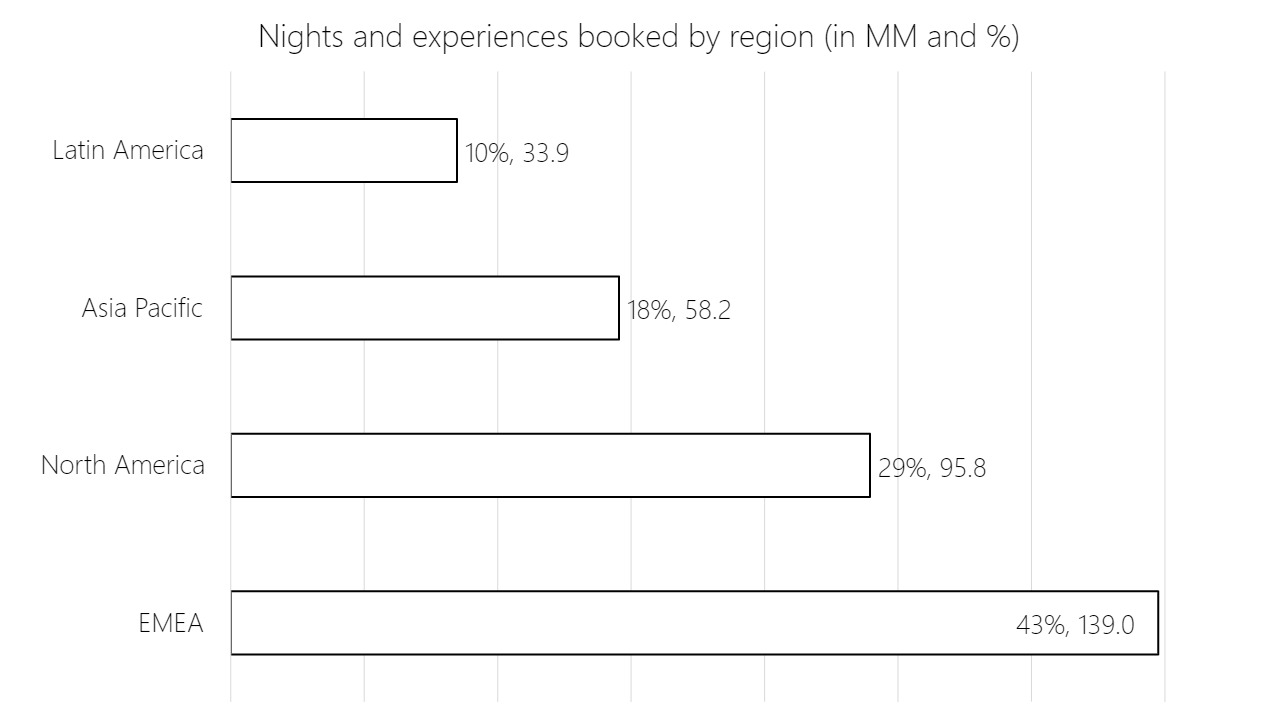

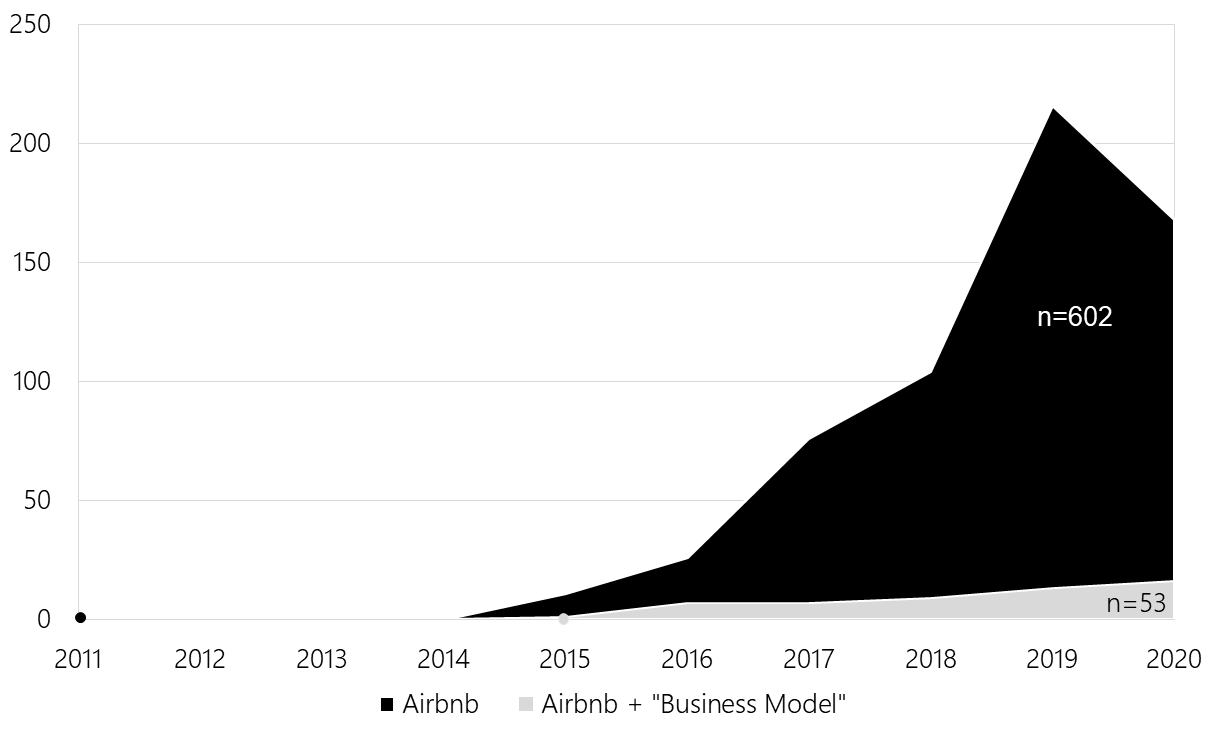

As of July 2020, Elsevier’s Scopus database lists 602 scholarly articles on Airbnb published between 2011 and 2020 in English in peer-reviewed journals. About two thirds of them appeared in the fields of business (34%) and social science (29%). The first article mentioning Airbnb in Scopus was published by Robin Chase (2011) in the Journal of Urban Regeneration & Renewal. Of the 602 articles, 46% appeared in tourism and hospitality journals, with the International Journal of Hospitality Management (45 articles), Annals of Tourism Research (26 articles), and Tourism Management (23 articles) the main outlets. The focus of most studies is on guest and host behaviour, the interaction among different stakeholders, and regulation. Only 53 articles address the business model of Airbnb, with the first one published by Daniel Guttentag (2015). Most of these articles do not analyse Airbnb’s business model as an integrated logic of value creation and capture. They thus fall short of meeting the standards of the broader research program on business models as a theoretical concept (e.g., Foss & Saebi, 2018; Massa et al., 2017).

Figure 2.1 shows the number of Scopus-registered articles published by year for the search terms Airbnb and Airbnb + “business model”. The first publications for each set are marked with a colour-corresponding dot. The sharp increase in 2019 is partially explained by Annals in Tourism Research launching its virtual curated collection on peer-to-peer accommodation leading to a surge in new submissions. The slight decline between 2019 and 2020 is likely explained by the cut-off of the search in July 2020. At the time of writing, there was another half year for new articles to be registered on Scopus.

This review of scholarly work on Airbnb shows that only few studies focus specifically on Airbnb’s business model. This is an important omission. Understanding Airbnb’s business model shows how the design choices as a dynamic equilibrium (Demil & Lecocq, 2010) have shaped and are being shaped by the evolution of Airbnb and its interactions with guests, hosts, and other contextual contingencies. Those interactions determine the success of the platform, the viability of its facilitator, the dependability of services for guests and hosts, and externalities experienced by other stakeholders. The business model perspective provides insights into how Airbnb’s context and business model shape one another.

In this chapter we explore in detail the evolution of Airbnb’s business model across three distinct development periods. We draw on existing academic publications on peer-to-peer accommodation, industry and media reports, and public archival sources to reconstruct Airbnb’s business model at various points in time, and transformations over time. This approach enables us to reconstruct a detailed account of how Airbnb creates, captures, and disseminates (non-)monetary value, and outline avenues for further research.

Business model versus strategy

Interest in the business model was triggered in the mid-1990s during the dotcom boom (DaSilva & Trkman, 2014). Today, it is an interdisciplinary research stream in its own right (e.g., Bigelow & Barney, 2020; Lecocq et al., 2010), which has been used across a number of industries including tourism (e.g. Reinhold et al., 2019; Reinhold et al., 2020) and what is generally referred to as the sharing economy (e.g. Kumar et al., 2018; Ritter & Schanz, 2019).

At its core, the management concept of the business model is a description of how value is created, captured and disseminated by an entity, typically an organisation (Bieger & Reinhold, 2011). Analysing an organisation’s business model is a powerful approach (Reinhold et al., 2017) to understanding how it works (e.g., Zott & Amit, 2010) by investigating observable attributes. Examples of observable attributes of interest include how an organisation prices its services and how it designs segment-specific services. The business model also observes staff perceptions of how an organisation operates – their mental models (e.g., Martins et al., 2015). These perceptions determine to a significant extent decision-making in organisations because they allow decision makers to anticipate the results of alternative decisions. The intimate understanding of an organisation derived from the analysis of its business model can serve as the basis for redesigning the organisation or creating an entirely new organisation (e.g., Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2009; Sinfield et al., 2012).

The business model connects an organisation’s strategy with its operations (Bieger & Reinhold, 2011). Strategy outlines the direction in which an organisation is moving. Operations are specific tasks which an organisation needs to perform in order to move into the direction set out in its strategy. While an organisation’s business model captures the bigger picture, like business strategy does, the two concepts are distinctly different from one another (Bigelow & Barney, 2020). Strategy is forward-looking and sets out the organisation’s scope, its unique selling proposition among the competitive field in the market, and how the organisation generates value for shareholders (Massa et al., 2017). The business model in itself is not forward-looking. Rather, it is a description of the present moment. The business model specifies how the organisation, presently, creates value for its customers, captures value, and how it disseminates it further to its suppliers and business associates. The business model is not aspirational, it is “a reflection of a […] realized strategy” (Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010: 205). As such it is particularly valuable to organisations who do not have a clear strategy (Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010). A strategy cannot be fully recreated by observing how an organisation operates. Its business model can be.

For the present analysis, we focus on the integrative story (Bigelow & Barney, 2020; Doganova & Eyquem-Renault, 2009) that provides insights into the evolution of Airbnb’s business model over time. We base our analysis on the value-based business model framework (see Table 2.1, which “(1) determines what an organization offers that is of value to the customer (i.e., the value proposition), (2) how it creates value within a value network, (3) how it communicates and transfers this value to customers, (4) how it captures the created value in form of revenues and profit, (5) how the value is disseminated within the organization and among stakeholders, and finally, (6) how the value is developed to ensure sustainable value creation in the future” (Bieger & Reinhold, 2011: 32).

| Element | Definition |

|---|---|

| Value proposition | What an actor offers that is of value to distinct customer groups (i.e., product, service, or any other unit of business) and how it is of value to those groups |

| Value creation | How an actor fulfils the value proposition by combining proprietary and external resources and capabilities in collaboration with suppliers and other partners |

| Value communication and transfer | The channels an actor uses for exchange with customers to communicate and fulfil the value proposition and/or building a relationship |

| Value capture | How an actor directly or indirectly acquires monetary and/or non-monetary rewards from customers by fulfilling the value proposition |

| Value dissemination | How an actor disseminates the acquired value to suppliers and other partners to reward their support and sustain their contribution |

| Value development | How an actor develops its business model in evolutionary and revolutionary terms to ensure the long-term viability of its business |

The evolution of Airbnb’s business model

The business model configuration used by Airbnb is called a multi-sided platform model (Rumble & Mangematin, 2015; Reinhold & Dolnicar, 2018a; 2018b); a term coined in the field of economics (Rochet & Tirole, 2003). As the name implies, a platform stands at the centre. The business runs the platform; it serves as the platform facilitator. The platform connects two sides, in the case of Airbnb: guests who need short-term accommodation and hosts who have available space and are interested in renting it out for short periods of time. Additional stakeholders can also be involved in multi-sided platform businesses. Professional photographers, for example, assist Airbnb and hosts to present available spaces in the most attractive possible manner.

A deep theoretical understanding of multi-sided platform businesses was not the starting point of Airbnb being founded. Rather, it was the result of a long and ongoing learning and development process as the subsequent quote from Jeroen Merchiers (Airbnb Managing Director of Europe, the Middle East and Africa) illustrates:

“When the founders started Airbnb 10 years ago with a few air mattresses in their apartment, they had no idea what the company would become. They simply found a creative accommodation solution at a time where there was no availability at nearby hotels. But they soon realized, as they hosted their first guests, that Airbnb can offer far more than just an air mattress on the floor. It could offer a much more personal and unique experience for guests provided by locals who know the area.” (Ting, 2018a)

The subsequent sections portray and discuss the evolution of Airbnb’s business model from its origins in 2008 to the alternate pandemic travel reality created by the COVID-19 pandemic in mid-2020. We detail the initial business model configuration (2008 – 2016), track experiments and different growth paths on the way to initial public offering (2017 – 2019), and finally assess Airbnb’s COVID-19 response up to and including the organisation’s initial public offering on the stock market. Figure 2.2 provides an overview of critical milestones across these three periods. The milestones at the top mark changes in the elements of Airbnb’s business model and achievements. The milestones at the bottom provide information on funding for the company. We close this section with observations on the overall development. Our arguments and analysis are grounded in in public archival sources and industry publications detailing observable changes in the key attributes of Airbnb’s business model. It should be noted that although the chapter is divided into defined time periods (e.g., 2008 – 2016), some events extend across multiple periods.

![Timeline showing Airbnb milestones and funding from 2007 until present (2020). Airbnb milestone timeline: Fall 2007: Airbedandbreakfast.com August 2008: Formal website launch; Democratic Convention (US) March 2009: Name change to Airbnb Feb 2010: 1 million bookings, 89 countries Summer 2011: First foreign office May 2012: $1m host guarantee June 2012: 12 million bookings Summer 2014: More than 100,000 guests during Rio world cup October 2014: Airbnb law in San Francisco November 2016: Friendly buildings program November 2016: Airbnb Experiences February 2017: Acquisition of Luxury Retreats December 2017: Niido home sharing apartments February 2018: Airbnb Plus & Concerts March 2019: HotelTonight and 0.5b arrivals November 2019: 9 year sponsorship with Olympics March 2020: $260m host relief package May 2020: 25% workforce cut December 2020: Initial Public Offering Airbnb funding timeline: 2008: [Financial crisis October 2008] Selling cereal boxes ($30,000) 2009 – 2011: Seed funding ($20,000) Y combinatory, Seed funding ($615,000) Sequioa, Series A funding ($7.2m) 2011 – 2013: Series B funding ($114.9m) 2013 – 2015: Series C funding ($200m), Series D funding ($520m) 2015 – 2017: Series E funding ($1.7b), Series F funding ($1b) 2017 – 2021: [COVID-19 pandemic March 2020] Private Equity ($1b), Market launch valuation for ABNB ($100b)](https://uq.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/10/2021/03/Airbnb-Milestones-2008-2020-14042021-e1618364107683.png)

Developing the initial business model configuration (2008 ‒ 2016)

Developing a new business model in an undeveloped market (“alternative tourist accommodation offered in people’s homes”) is a complex endeavour. Hence, designing what is still at the core of Airbnb’s value creation logic to this day, was the result of years of trial-and-error. It shaped the different mechanisms Airbnb uses to create and capture value from connecting guests, hosts, and third parties.

Value proposition

Table 2.2 summarises Airbnb’s value propositions to hosts who list space on its platform Airbnb.com, to guests who use the platform to book short-term accommodation and to all other service providers who support any of the core providers within the network. These aspects remain essentially unchanged, apart from the additions between 2017 and 2020 outlined in later sections.

Value proposition for…

| Hosts | Guests | Third parties |

|---|---|---|

| Identify suitable guests | Find accommodation | Find and engage with new clients |

| Mitigate risk | Offer convenient booking | |

| Handle monetary transactions | Mitigate risk | |

| Maximize revenue | Augment experience | |

| Administer the short-term rental | ||

| Connect with like-minded hosts |

Proposition to hosts

The primary reason for hosts to list space on Airbnb’s online platform is to find trading partners – people who are willing to pay for access to these spaces. Hosts may be motived by a range of different benefits that are important to them (Karlsson & Dolnicar, 2016), including maximising return on a property investment, earning an income, supplementing their income, covering the expenses associated with having a holiday home, meeting new people, or putting space that otherwise sits idle to good use.

Airbnb’s online platform attracts hosts with very different patterns of motivation, which have been classified by different authors in different ways. At the most fundamental level, hosts can be grouped into professionals and non–professionals (Farmaki et al., 2019; Li et al., 2016). Splitting up the non-professionals leads to three segments of hosts: capitalists, befrienders and ethicists (Hardy & Dolnicar, 2018a). Even finer groupings differentiate between economic hosts, eco-socio hosts, socio-eco hosts and social hosts (Sweeney & Lynch, 2009) and pragmatists, petty tycoons, conflictual owners, extrinsic owners, and lexi-owners (Darke & Gurney, 2000).

Irrespective of the reasons for wanting to host, it is extremely difficult to do so unless potential buyers are aware of the offer. Developing a webpage to showcase one’s space is one solution, but it does not offer the same value as listing space on Airbnb.com. Airbnb’s value proposition to hosts developed between 2008 and 2016 is multi-faceted: Airbnb’s online platform: exposes the listing to a very large number of potential buyers, limits the host’s risk associated with letting strangers stay at their property, manages payments, handles additional administrative matters (such as providing information about access, internet passwords etc.), and provides hosts with access to thousands of other people who are part of the network to connect with, share experiences with and learn from.

Airbnb.com helps hosts to identify suitable guests by showcasing the property in a lot of detail, and in a standardized way familiar to guests, to 150 million Airbnb members living around the world. This is a very strong value proposition because of the size of the network. The more members – potential buyers – that are part of the network, the more exposure the listing gets and the likelihood of being booked increases. The search interface on Airbnb.com facilitates the identification of good matches between buyers and sellers of space – guests and hosts. Guests are offered an extensive list of accommodation characteristics which they can choose from to ensure that search results are suitable for their needs and attractive to them. Examples include: whether the property has a pool, a secure undercover parking space, a spa, and Wi-Fi. In addition to these searchable criteria which are coded in binary format on the trading platform, each Airbnb listing also offers a substantial amount of detail, including a detailed description and a large number of – often professional – photos. These sections of the listing enable hosts to ensure that the uniqueness of their property is communicated and illustrated well to potential guests. Underlying the Airbnb.com webpage visible to Airbnb members is a sophisticated algorithm that presents listings in an order that maximises bookings.

Risk is the main concern hosts have when they make space available to strangers (Karlsson et al., 2017). Airbnb’s value proposition of risk mitigation, therefore, is hugely important. Airbnb has in place a range of mechanisms to reduce the risks associated with short-term space trading. The identities of all Airbnb members are verified. Hosts have the possibility to read reviews of guests sending booking enquiries. These reviews are provided by other hosts, who have previously made space available to these guests. Over time, guests develop what has been referred as a peer-to-peer accommodation network curriculum vitae (P2P-CV, Dolnicar, 2018): a long list of reviews from other hosts. A large number of positive reviews gives a host confidence that it is safe to make their property available to these guests. Airbnb also has a very generous host guarantee, which “provides up to $1,000,000 USD in property damage protection in the rare event a host’s place or belongings are damaged by a guest or their invitee during an Airbnb stay” (Airbnb, 2020a). This host guarantee is critically important given the amount of negative press generated every time an incident occurs at an Airbnb property.

Most hosts are not professional e-commerce retailers. The fact that Airbnb handles all payments, therefore, is of significant benefit to them. Guests can pay using the most commonly used online payment options in their national currency. Airbnb handles the rent payment, including any surcharges and cleaning fees that may apply, as well as managing transactions associated with cancellations, and collecting and holding a deposit from the guest in case the host notices damage and requests within 24 hours of check-out for the damage to be paid for by the guest. Electronic handling of payment well before check-in is safer and avoids any socially unpleasant situations between guests and hosts at the time of the stay.

Closely related to managing payment is also the pricing strategy of a listing. Airbnb offers a value proposition for hosts in this area also, by helping them maximise revenue. This is not only achieved by the algorithm that matches guests with the most suitable listings, but also by making pricing recommendations to hosts for every calendar day based on the features and location of their property, and historic data of booking prices for similar properties. Hosts can choose to use these pricing recommendations, or, alternatively, to set their own price, overriding Airbnb’s recommendations.

Another key Airbnb value proposition is assistance with the administration of a listing. When a host decides to list a property, they need to take action with respect to a range of areas: they need to provide certain information about the property (such as location, Wi-Fi password), ensure that the property has the safety features required under local laws and regulations (such as fire alarms, exit signs on doors and an emergency evacuation plan), and be able to signal to guests interested in booking their property whether or not it is available on specific dates. The highly structured and standardised setup of a listing on Airbnb guides hosts through all these steps. The Airbnb platform also forces hosts to take action when regulations or circumstances change in critical ways. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, as discussed later in this chapter, hosts had to agree to stricter cleaning procedures. While Airbnb cannot police compliance with these procedures, the process of committing to them alerts hosts to how they need to modify their procedures, effectively offering a checklist

The value proposition of connecting like-minded hosts is one that is appreciated by some hosts more than by others. Many Airbnb hosts use Airbnb.com as a distribution platform and have no interest in engaging with other Airbnb members. Others are very active on the platform and its discussion groups via the Airbnb Community Center, which invites hosts to “share knowledge, get inspired and meet other hosts who are creating a world where anyone can belong” (Airbnb, 2020b). The Airbnb community facilitates online exchanges between hosts, but hosts also have the opportunity to meet in person or use alternative communication platforms once they are connected. A very active and vocal group of Tasmanian Airbnb hosts, for example, uses a Facebook group to talk and coordinate their actions (Hardy & Dolnicar, 2018b; Hardy et al., 2021).

Proposition to guests

Airbnb.com also offers several value propositions for guests, whether they are travelling for business or for pleasure. At the most fundamental level, Airbnb’s online trading platform helps guests find suitable accommodation. The search for accommodation is facilitated on Airbnb.com in many ways: it enables directed searching using a range of search criteria, including geographic location, price, size, and rating by other guests as well as a substantial list of criteria which are used to describe – in binary format – each listing. Criteria developed between 2008 and 2016 include the nature of the listing (shared space or entire property), whether the host is a Superhost, and whether it has: a kitchen, heating, air conditioning, a washing machine, a dryer, Wi-Fi, a TV, an indoor fireplace, hangers, an iron, a hair dryer, a cot, and a highchair. Other default searchable criteria include safety-related aspects such as whether the space is equipped with a smoke alarm and a carbon monoxide alarm, whether there is a dedicated workspace, whether self-check-in is possible and whether breakfast is provided. More search filters are accessible to guests for specific requirements, such as a pool, a spa, free parking, a gym, and whether the property allows pets.

Guests can search by scrolling through listings, looking at one picture and a few key facts about each property or by locating properties on a map. Clicking onto one specific listing provides access to a very detailed property profile, much more detailed than those provided by established tourism accommodation providers. Listings include a substantial number of pictures, an overview of the key features of the property, the amenities provided, cancellation terms, reviews by other guests, detailed – sometimes quite lengthy – information about the property, whether pets are allowed, and whether smoking is permitted. The listing also directs people searching for accommodation to the profile of the hosts, and provides information about the neighbourhood, including tips provided by hosts themselves. The large number of daily searches conducted on Airbnb.com is harvested by Airbnb to identify search patterns and deploy search optimisation algorithms to present people with the listings that are likely to be most attractive to them.

The Airbnb online trading platform also facilitates a different kind of search: entirely undirected searching guided by browsing the webpage and deriving inspiration from the content. Such undirected searching has become even more attractive since Airbnb introduced Experiences in 2016 across a wide range of areas, including sport, food and entertainment (Gardiner & Dolnicar, 2018; 2021). Experiences refocus the search to activities. Once an interesting Experience is identified, the location follows, and accommodation can also be booked on Airbnb.com.

A value proposition in its own right is also the convenience of booking using an online booking platform. When suitable accommodation is identified, the booking process is very easy. It only takes a few clicks and the credit card details. The level of convenience has further increased in recent years as a consequence of Airbnb introducing the Instantbook feature. When a host activates Instantbook, guests can book the accommodation without having to send a request to the host. Sending a request to the host and potentially being denied permission to book the selected accommodation was a key feature of Airbnb as it was originally designed, as it gave hosts control, and with it, confidence in giving access to their house to strangers (Dolnicar, 2018a). Booking convenience on network platforms is known to represent a key factor in perceived service quality (Priporas et al., 2017; Varma et al., 2016). On Airbnb.com the booking process is standardised. Airbnb manages all payments, which means that no money transfers – and certainly no cash payments – are required directly between guests and hosts. Payments can be made using most available standard payment options supported by banks.

Booking a private space via an online booking platform helps guests to mitigate risk. Many things can potentially go wrong when booking space from a non-licensed provider, especially when the space is shared with the host or other guests. For a relatively small service fee charged by Airbnb to guests, guests benefit from a range of risk-mitigation measures put in place by Airbnb:

- The identity of all network members is verified. At the very least, this identification process involves their telephone number and email address. Network members can also choose to list links to their social media profiles, their location of residence and provide official identification documents.

- Before a booking is confirmed, Airbnb does not share the guest or host’s private data, and does not transfer money to the host until 24 hours after the guest has checked in, making it easier to handle refunds if the guest finds the accommodation to either not exist at all or be unacceptable and not as presented on the online listing.

- Guests and hosts are encouraged to write reviews about one another. Guest reviews include a star rating for cleanliness, communication, check-in, accuracy, location and value. Guests can also provide a more detailed evaluation in an open text field. The sum of all reviews forms the host’s peer-to-peer accommodation network curriculum vitae (P2P-CV, Dolnicar, 2019), just as it does for guests. The availability of these host P2P-CVs gives guests the opportunity to inspect them before deciding to book accommodation. Airbnb further adds value by allowing hosts to respond to what they believe to be inaccurate accusations.

- Although Airbnb does not mandate safety devices, it encourages hosts to take several measures to reduce risks to guests through a separate safety section on the listing profile. Here, hosts declare if there is a pool or spa without a gate or lock, if the accommodation is near a lake, river, or other body of water, if there is a climbing or play structure, if there are any elevated areas without rails, or any potentially dangerous animals. If any of these things apply, the host is asked to provide additional information. Hosts also indicate if the space has security cameras or audio recording devices, a carbon monoxide alarm, and smoke alarms.

- Airbnb has a guest guarantee, giving people confidence that alternative accommodation will be arranged if the booked Airbnb property does not exist or is unsafe.

While the core focus of Airbnb is on the trading of accommodation, guests can derive additional value from a wide range of Experiences (Gardiner & Dolnicar, 2018; 2021) that can also be booked on the platform. In addition, Airbnb encourages hosts to provide local recommendations which are not related solely to the accommodation, but also encompass dining experiences and attractions, among other things. This authentic, local, personal insider knowledge augments the experience compared to booking accommodation using established commercial accommodation providers.

Proposition for third parties

To third parties – businesses involved peripherally with peer-to-peer accommodation trading – Airbnb also offers a value proposition: revenue generation by providing services that are not provided by either Airbnb or the host. Such additional services (for examples from the first period see Table 2.3) are embedded on the trading platform, but not operated by Airbnb. One example is the professional photography service for listings.

| Firm | Service |

|---|---|

| Guesty | An integrative platform to manage multiple accommodation rentals via a single, integrative, cloud-based solution (www.guesty.com) |

| HonorTab | A minibar-like service that allows hosts to manage inventory and charge for groceries and other consumable amenities (shampoo etc.) (honortab.com) |

| Hostmaker | A management company for accommodation rentals that handles everything from furnishing, to listing, housekeeping, pricing, and maintenance (hostmaker.co) |

| Keycafe | A service that mediates access to accommodation rentals by providing pick-up and drop-off points from lockers (keycafe.com) |

| Pillow | A management company for accommodation rentals ‘that takes the work out of renting your home or apartment’. They provide similar services to Hostmaker but add a focus on facilitating collaborative solutions for short-term rental that work for building management and residents (pillow.com) |

Another example is the possibility for professional co-hosts to assist hosts with their Airbnb operations. Airbnb has set up an interface where co-hosts are formally involved in the process, rather than having to illegitimately operate through the hosts’ login credentials. Co-hosting offers significant entrepreneurship opportunities to third parties (Sigala & Dolnicar, 2018; Fairley et al., 2021a). Ultimately the value proposition is the ability for businesses and entrepreneurs to attract new clients. An entire ecosystem (Adner, 2017) of third-party providers depends on the trading occurring on Airbnb.com.

Value creation

Airbnb creates value for hosts, guests, and third parties through activities and resources, and input from business partners. Table 2.4 offers a summary of the five key activities and five key resources Airbnb leverages to generate value. The term key activities refers to standard operating procedures – routine behaviours (Feldman & Pentland, 2003) – that make it possible for Airbnb to make the value propositions discussed above. Key resources are the building blocks Airbnb relies on to perform the key activities. Optimally, key resources are under full control of Airbnb and, as such, cannot be imitated by competing facilitators of peer-to-peer accommodation trading.

| Key activities | Key resource |

|---|---|

| Growing and nurturing guest and host networks | Tailored marketplace |

| Search optimization to match guests and hosts | Trust-base relationships |

| Understanding and tracking guest and host behavior | Database of reviews tied to profiles |

| Building confidence by mitigating risk | Knowledge resources |

| Cost management | Service recovery staff |

Key activities

A handful of key activities drive Airbnb’s success. The first one is to attract and retain a large number of Airbnb hosts and guests (growing and nurturing guest and host networks). By definition, the attractiveness of any market of trading platform depends on how many potential trading partners are available in the market or on the trading platform. As the number of potential trading partners increases, so does the attractiveness of the market or trading platform. The technical term relating to this attractiveness is network effect (e.g., Hagiu & Wright, 2015). A network effect occurs when the value of a service – in this case the functionality of Airbnb.com – increases with the number of network members.

As soon as a market or trading platform reaches a critical mass of buyers and sellers, a self-reinforcing cycle is activated: markets and trading platforms with many members attract more members and continue to grow to a point where they can dominate entire markets. This is exactly what happened in the case of Airbnb. Airbnb put substantial efforts into the initial growth of its membership between 2008 and 2016, including employing growth managers whose sole purpose is to attract more network members. Airbnb has taken a wide range of different approaches over the years to grow its membership. When Airbnb launched originally, the founders of the company personally door-knocked to increase the number of listings on Airbnb.com, and organised events dedicated solely to the recruitment of hosts (Gallagher, 2017).

Airbnb also tapped into the pool of people already listing rooms and apartments on online platforms – such as the US classifieds webpage Craigslist –and offered them co-listing opportunities (Brown, 2017; Gallagher, 2017).

Using Facebook, Airbnb launched an early advertising campaign in San Francisco and New York. The aim of the campaign was to communicate how much money people could earn by selling access to their homes while they were on vacation. The key argument was that people could in fact fund their vacation by renting out their homes while enjoying their holiday (The Economist, 2015). To minimise the cost associated with making space available on its online trading platform, Airbnb did not charge a listing fee – much in contrast to other peer-to-peer trading platforms (The Economist, 2012). This pricing strategy signalled to potential host that listing on Airbnb.com was risk free: it may lead to revenue, but it will not cause any cost (except the time hosts invest in setting up the listing).

In an attempt to expand their network globally, Airbnb acquired businesses in the UK and Germany that imitated the Airbnb.com platform in the first period. This approach was highly effective in growing the number of local Airbnb hosts quickly, platform by platform, rather than host by host (Brown, 2017). Where this was not possible, or where it proved too expensive to acquire competitors, Airbnb reverted to its original growth strategy of personal door-knocking by teams of staff to proactively recruit local hosts in international markets (Yip, 2017).

Although Airbnb is now well-established globally, its recruitment efforts are ongoing. Its referral program, for example, allows hosts to invite their friends to list space on Airbnb. If they do, Airbnb gives them credit to use when they make their first booking on Airbnb as a guest. As soon as the new host has welcomed their first Airbnb guest, the host who referred them is also given credit that they can use for their next stay at an Airbnb-listed property (Brown, 2017). Word of mouth also played a key role in recruiting new hosts. Airbnb fuelled word of mouth by its storytelling initiative, which facilitates the sharing of travel experiences among Airbnb members (Yip, 2017). Airbnb also ran advertising campaigns using a range of communication channels (Wegert, 2014) emphasising the advantages of booking Airbnb-listed accommodation (Davis, 2016), and targeted advertisements using Google, amplifying its own search engine optimisation algorithms.

Events that lead to a temporary, but substantial increase in demand for tourist accommodation (Brown, 2017), often characterised by accommodation shortages (Fairley & Dolnicar, 2018; Fairley et al., 2021) are another key recruitment opportunity for Airbnb. Such events include major sports events, conventions, conferences and festivals. In such situations, Airbnb can unlock vacant unused space temporarily to help overcome accommodation shortages, while enabling locals to earn additional income. Locals who would otherwise not have considered hosting may take the opportunity to try it out. Furthermore, guests who would usually prefer to stay in established, licensed tourist accommodation may choose an Airbnb-listed property because of the high prices of hotels and similar accommodation options at times when demand is high.

The second key activity Airbnb engages in to create value is to facilitate the matching process on the online trading platform (search optimisation to match guests and hosts). People searching for accommodation are not interested in the largest set of options. Rather, they want to be presented with a reasonably sized, relevant set of accommodation options that matches their requirements and preferences. This is where Airbnb’s secret search algorithms come into play. Optimal matching of listed properties with guest needs – micro segmentation (Dolnicar, 2018) – gives an online trading platform a substantial competitive advantage in the marketplace. Although Airbnb does not disclose the exact optimisation algorithm (which was supervised by some 400 engineers and data scientists as of 2016), existing reports point to two key features of the algorithm that make it so effective (Gallagher, 2017): the design of its search platform Airbnb.com, and the use of search engines such as Google that facilitate targeted displays of search results. For example, Airbnb targeted advertising by optimising Google AdWords (Gallagher, 2017; Google, 2014) and Display Ads (Wheeler, 2014).

The algorithm Airbnb uses on its own trading platform takes more than 50 aspects of guest-host matching into consideration, including: the property’s location and type of space; its star rating across reviews; the number of reviews available for a listing; how quickly a host responds to guest enquiries; if a property can be booked without having to wait for the confirmation from the host; if the required travel dates are available; and how expensive it is. By understanding how Airbnb processes listings, hosts can optimise the visibility of their property in guest searches by ensuring they perform well on the key criteria, including responding to enquiries, responding quickly, not cancelling bookings, providing many forms of identity verification as well as pricing the property competitively and including many pictures. Importantly, no two identical searches by two Airbnb guests will lead to the same properties being displayed. This is because Airbnb personalises the presentation of available listings to the preferences of network members learned through their previous searches and bookings (Ifrach, 2015). In Table 2.4 this activity is listed as understanding and tracking guest and host behaviour.

In addition to digital platform optimisation, Airbnb also engages personally with hosts to understand their needs, what they like about listing their properties on Airbnb, and what they think could be improved. When Airbnb started its operations, the founders of the company themselves interacted directly with hosts to gain market insight. While such individual conversations became unviable as the number of listings climbed into the millions, Airbnb moved to organising large events to facilitate the personal exchange between Airbnb staff, hosts and host service providers. Airbnb’s flagship event is the Airbnb Open, which Airbnb refers to as “the festival of hosting” (Airbnb, 2017). Airbnb Open events have been held in San Francisco, Paris and Los Angeles.

Overall, however, personal meeting and conversation opportunities have – over the years – given way to machine learning and behavioural modelling, which allow Airbnb to gain insights into people’s preferences by mining large transaction data sets (Sng & Hachey, 2016). This development has not been welcomed by Airbnb hosts, especially those Airbnb hosts who have been the pioneers of peer-to-peer accommodation provision (Hardy & Dolnicar, 2018b) and have become used to interacting with humans at Airbnb. Yet, the data generated on a continuous basis by Airbnb.com opens up new business opportunities for Airbnb. Its transaction data has the potential to provide key insights informing decision-making by tourism industry professionals, urban planners, the real estate sector, and tax authorities – as events discussed later in this chapter will demonstrate. Airbnb could mine data and sell insights or even sell de-identified data, creating an entirely new revenue stream.

Risk mitigation is another key activity Airbnb engages in. Before Airbnb became a successful peer-to-peer accommodation trading platform, potential investors raised significant concerns about the proposed business model, suggesting that “the idea of renting out space to strangers [is] totally weird and unbelievably risky” (Gallagher, 2017: 16-17) and that “the very idea of letting strangers sleep in their homes was asinine [and] simply asking for trouble” (Gallagher, 2017: 49-50). While these concerns did not prevent Airbnb from becoming successful, it is true that giving all network members confidence in the platform and the transactions made on the platform (Dolnicar, 2018) was critically important to Airbnb’s business model. Not surprisingly, much of Airbnb’s effort was directed toward the building of trust. A dedicated Airbnb Trust and Safety Division manages a portfolio of strategies put in place to reduce host and guest risk and risk perception, and to increase trust and confidence in the platform.

Airbnb has put in place several measures targeted at hosts, including the host guarantee providing protection against damage to a host’s property or belongings (Airbnb, 2020a), the ability to access guests’ P2P-CVs containing the numerical and verbal reviews written by people who have previously hosted these guests, and identity verification. Airbnb provides information on their webpage for hosts about the local regulatory requirements in relation to short-term rentals. At popular tourist destinations, these regulations typically include requirements to register, to pay a tourist tax, and to comply with specific criteria relating to guest safety (Hajibaba & Dolnicar, 2018; Von Briel & Dolnicar, 2020; 2021a). In some destinations, policy makers allow Airbnb to collect and pay taxes on behalf of hosts.

Risk mitigation is also a core Airbnb activity with respect to guests. Airbnb protects guests in a number of ways. Paying hosts with a slight delay is one of these approaches. The 24-hour payment delay ensures that hosts listing non-existent properties or properties that are substantially different in reality to how they were presented online are not paid. In such instances, guests are able to contact Airbnb and have alternative accommodation organised. Another way for guests to reduce risk is to study the P2P-CVs of hosts. These P2P-CVs consist of all reviews guests have ever written about the host and the property. A large number of positive reviews gives guests confidence that they will not be disappointed. Airbnb also verifies the identity of hosts and set up the property listing in a way that ensures that hosts include detailed safety-related information, including which safety devices are at the property, evacuation plans and emergency contact details. The Airbnb Community Defence Team spot-checks listings, and data scientists monitor trading transactions on Airbnb.com for any potentially fraudulent activity, and Twitter and Facebook posts for Airbnb-related distress calls (Gallagher, 2017). Airbnb also has crisis management, victim advocacy, insurance, and law-enforcement relations teams; all working under the supervision of Airbnb’s Trust Advisory Board (Gallagher, 2017).

The final key activity is the management of cost. Airbnb’s revenue model works on the assumption that a large number of trades occur on Airbnb.com, each only contributing a small profit margin. This explains why Airbnb charges hosts only a relatively low fee for its services compared to other tourism accommodation distribution channels. The low fee, in turn, attracts more hosts because they perceive Airbnb as a cost-effective distribution channel. As a likely consequence of the small profit margin Airbnb makes for each transaction, Airbnb has strict cost control measures in place (The Economist, 2017).

Key resources

Airbnb’s key resources include a tailored marketplace, trust-base relationships, an extensive database of reviews tied to network member profiles, knowledge resources, and service recovery staff. These resources enable Airbnb to engage in the key activities discussed above and, in so doing, create value for all its stakeholders. Key business resources are particularly beneficial to a business if they cannot easily be copied, offering a substantial competitive advantage in the marketplace (Barney, 1991). The extent to which Airbnb’s key resources can be imitated by competitors varies from resource to resource.

The tailored marketplace, Airbnb.com, is one of the keys to Airbnb’s success. When Airbnb started operating, its online trading platform was custom designed to facilitate all the key functions necessary to present listings in the most attractive way possible, facilitate high numbers of trades simultaneously without crashing, build a community, protect all network members, create trust through a reciprocal review system that allows for responding and resolution (Dolnicar, 2019), and manage international financial transactions without requiring a bank licence (Gallagher, 2017). Airbnb’s tailored marketplace was not easy for competitors to imitate in the early days of Airbnb. Since the end of the first period, a number of off-the-shelf open-access and paid online marketplace solutions have been available to use by new market entrants to copy this aspect of Airbnb’s online presence (von Briel & Dolnicar, 2021b)

Airbnb’s second key resource is the trust-based relationships it has built with millions of hosts and guests globally over the years. This was extremely challenging for Airbnb because tourists were used to relying on licensed tourism accommodation providers. The licensing signalled to tourists that they could trust these accommodation providers. The providers themselves did not need to work to earn the trust of tourists, they could only lose this trust by providing inadequate services. Airbnb was in an entirely different position. It was trying to convince people to rent out their private spaces to strangers, and to book someone’s private space for their holiday. Trusting the trading platform is an essential requirement to be able to achieve this (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Developing trust as a resource takes a long time (Dierickx & Cool, 1989). In terms of competitors’ ability to imitate this resource, Airbnb’s efforts of trust-building have paid off. Airbnb is arguably the most trusted peer-to-peer accommodation trading platform globally, a resource that is very difficult to imitate. At the same time, Airbnb’s success in getting tourists to trust peer-to-peer accommodation in general also makes it easier for competitors to build trust into their platforms, as the base level of trust for peer-to-peer accommodation has increased substantially since Airbnb first launched.

Related closely to trust is another of Airbnb’s key resources: an extensive database of reviews associated with network member profiles. Every review benefits the entire network, allowing hosts to assess the suitability of a guest before confirming their booking and guests to assess the trustworthiness and professionalism of a host before sending a booking enquiry. The large collection of reviews and P2P-CVs that has accumulated on Airbnb.com is not easy to imitate for competitors because it is a function of the substantial number of trades that have taken place on Airbnb.com over the last decade. Hosts and guests who do not have a single review are at a significant disadvantage, representing a high risk for their potential trading partners (Dolnicar, 2018b). Reviews benefit Airbnb in another way: they highlight problems with listings which Airbnb may need to address, thus doubling up as a quality assurance instrument.

Knowledge resources are relevant to Airbnb in two ways. First, gaining market insights from millions of guest-host transactions requires knowledge on how to extract insights from data, while at the same time creating expertise in data mining for consumer insight at Airbnb, a resource that is available generally, but not easy to imitate by competitors with lower transaction numbers in the peer-to-peer accommodation space. The second dimension of knowledge resources relates to information libraries created by Airbnb to assist hosts. These include guidance such as setting up optimal listings, responding promptly and professionally to guest enquiries, dealing with complaints, complying with local regulations relating to peer-to-peer accommodation (Gallagher, 2017), and – more recently – cleaning properties in way that ensures no COVID-19 transmission between guests. Not all of this information is shared with the general public, with many knowledge resources embedded in Airbnb structures and procedures, including the Airbnb call centre (Sng & Hachey, 2016). While some of these knowledge resources for hosts can be easily imitated by competitors, others cannot.

The last of Airbnb’s key resources is a pool of call centre staff specialising in service recovery. Call centres can either be run by a business itself or can be outsourced. Outsourcing is typically the more cost-effective approach, but implies a lower level of control. Because building trust is of such fundamental importance in peer-to-peer accommodation trading, Airbnb has chosen to never outsource their call centre. Call centre service staff are critically important to building and maintaining positive relationships with hosts and guests, while also having to resolve critical situations involving safety risks. This key resource is not easy to imitate by competitors.

Only little information is available about how Airbnb’s partners and suppliers create value in this first period (Table 2.5).

| Partners | Suppliers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AmEx Global | Hipmunk To | Akamai Technologies | HootSuite Media Inc. |

| Business Travel | Amazon | Twilio Inc. | |

| AGR Investments | Lloyd Lyft Inc. | Dailymotion | Zendesk Inc. |

| Maximize revenue | Augment experience | ||

| Apple | MyAssist Inc. | EatWith Media Ltd. | |

| Boku Braintree | Pepsico | ||

| BCD Travel | Priceline.com | Flickr | |

| Carlson Wagonlit Travel | Penny & Co. | France Par | |

| Crucialtec Danal | Sequoia Capital | Gigamon Inc. | |

| Etisalat | Vayable Inc. |

The role of some of Airbnb partners is quite fundamental, as is the case with Amazon Web Services, for example. Amazon hosts Airbnb’s web services. As a consequence of the decision to use Amazon’s services, Airbnb does not need to manage hardware infrastructure, and is able to increase or reduce processing capacity quickly (Amazon, 2017; Gallagher, 2017). A different kind of partnership is that with business travel companies (Montevago, 2016). Here, Airbnb integrates its services with corporate travel programs.

Value communication and transfer

Airbnb.com is not only a point of sale for Airbnb. It is also the primary platform used by Airbnb to communicate with all of its active network members and people who are considering joining. Most communication is not individualised, yet offers support to hosts and guests and ensures the homogeneity of listings. Helpful, automatised communication includes, for example, a reminder email to hosts shortly before guests check in. This email ensures that hosts do not forget the arrival of guest. This may sound like an unlikely scenario, but with many hosts not being professional accommodation providers and hosting only as an additional source of income, such reminders are very useful indeed. Automatic emails are also sent to remind both guests and hosts to review each other on the day of check-out. This communication ensures that guest and host P2P-CVs grow continuously, increasing the value of Airbnb.com to all trading partners.

Most of Airbnb’s communication is not personal, rather it involves its web platform, its app, email, and advertising. In the early beginnings of Airbnb, personal contact was a key success factor in attracting new hosts. Over the years these personal contact opportunities became more organised and concentrated, for example, through hosting large events called Airbnb Opens where Airbnb staff, hosts, guests and host service providers had the opportunity to interact personally. Increasingly, these opportunities have become rare and interaction has been shifted online where Airbnb communities are encouraged to discuss any Airbnb-related matters.

Advertising and public relations play a key part in growing membership and retaining hosts and guests. In public, Airbnb focused strongly on communicating the concept of belonging in the first period (Marion, 2014). Marketing messages tended to be variations on this theme (e.g., ‘belong’, ‘belong anywhere’ ‘don’t go there. live there’, ‘until we all belong’), and fed into the curation of listing content, presentation of guidebooks and tips about local neighbourhoods (Davis, 2016; Wheeler, 2014). In addition to the highly emotional message of belonging, Airbnb also issued its own magazine (originally titled Pineapple and later renamed Airbnb Magazine), produced its own blog, created short films (including Birdbnb), and shifted content onto the full range of social media sites, including Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and Twitter (Wegert, 2014).

Airbnb.com’s messaging system – which serves as the platform for all communication – saves all messages sent and received, helping hosts with the filing of documents and serving as the basis for the resolution of any legal disputes or complaints by other network members (Gallagher, 2017).

Value capture

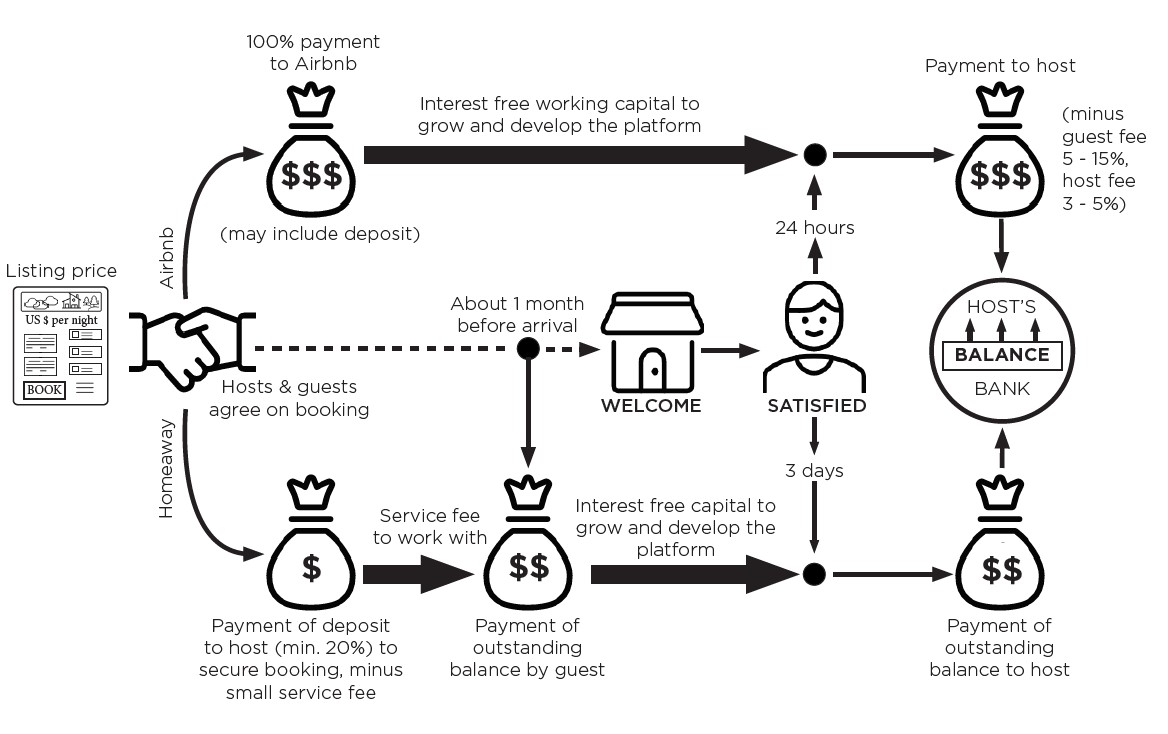

Airbnb captures value by charging a relatively small commission on all guest-host transactions. As opposed to other distribution channels, Airbnb split up this commission between hosts and guest with the guest fee between 5% and 15% of the price, and the host fee ranging from 3% to 5%. For comparison, Booking.com charges, as of 2020, an average commission rate of 15%, which is paid entirely by the accommodation provider (Booking.com, 2020). Booking.com claims that its commission rate average is “among the lowest in the industry”, suggesting that other tourist accommodation distribution channels charge an even higher commission rate.

Also in contrast to other distribution channels, Airbnb charges guests the entire amount of the accommodation at the time of booking. Airbnb deducts its commission and only releases the remainder to the host 24 hours after the guest checks in. This approach benefits Airbnb in two ways. First, it ensures – in the absence of complaints – that the listing actually exists and reflects the description on the listing, and second, it gives Airbnb access to the money for potentially extended periods of time. Peak season bookings are commonly made 12 months in advance; Airbnb having this money available to use for 12 months effectively represents an interest-free loan (Reinhold & Dolnicar, 2018d). This cash flow management model is also being used by Amazon; customers order and pay, then wait for days until the items they have purchased are delivered. During this period, Amazon can work with the money.

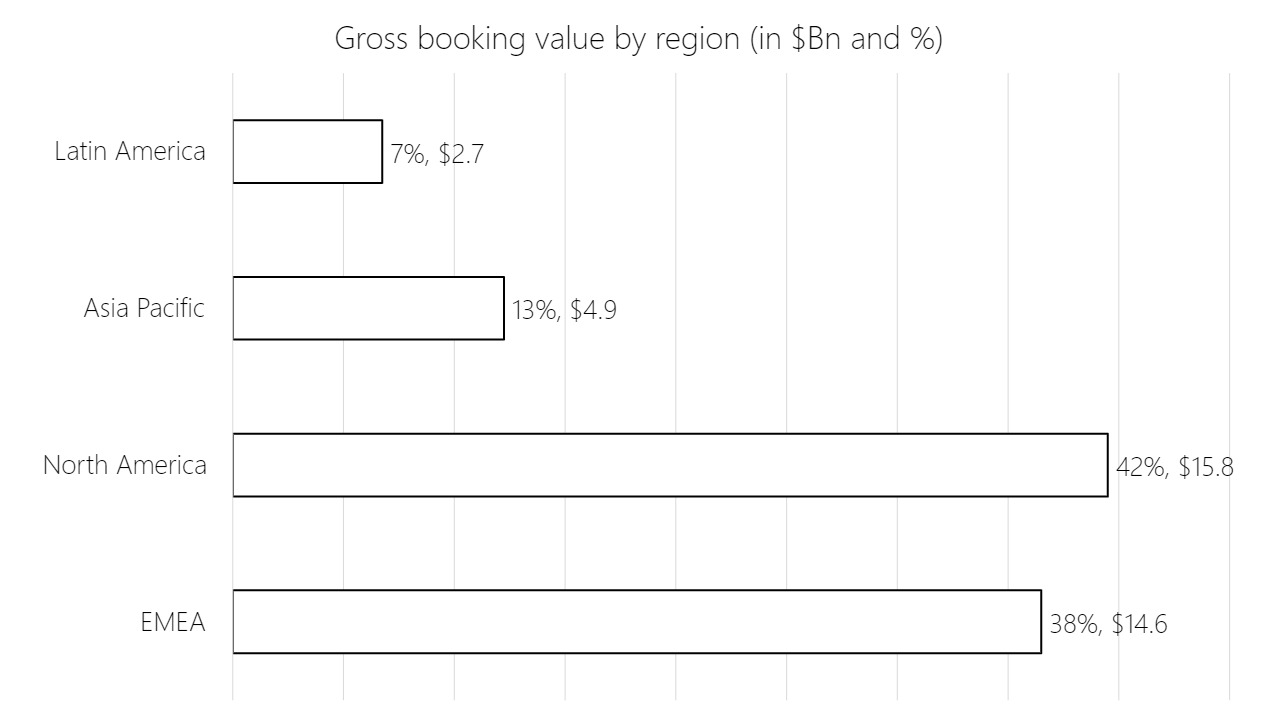

Figure 2.3 illustrates the money flows for Airbnb and Homeaway (now VRBO) as per the first period, highlighting the benefits Airbnb derive from its model.

For guests, Homeaway’s model is preferable – its payment plan includes a number of smaller payments leading up to the time of the booking. At the time of booking, Homeaway only charges a deposit of a minimum of 20%. Hosts can choose a higher deposit amount. In contrast to Airbnb, Homeaway immediately transfers the payment to the host, after having deducted its commission. The final payment is due one month before the booking. The host receives this amount three days after the guests have checked in. The security deposit is not due until one week before the booking. This money is refunded to the guest unless the host makes a damage claim after the guest has checked out.

The money-flow comparison shows the competitive advantage Airbnb derives from the way it manages payments. Airbnb can use the money guests have paid for accommodation well in advance of their booking to cover its expenses and expand its business.

Until December 2020, Airbnb was not a publicly traded company and was therefore not obliged to reveal details about its revenue and profit. However, the company is said to have first been profitable in 2016 with revenues projected to hit USD $2.8 billion in 2017 with its earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) at USD $450 million (Gallagher, 2017). Airbnb attracted – through ten investment rounds – some USD $3.34 billion of funding from 41 investors during the first period (Crunchbase, 2017), as shown in Table 2.6.

| Funding stage | Year | Capital raised | Airbnb investor valuation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seed | 2009 | $635,000.00 | $2,500,000.00 |

| Series A | 2010 | $7,200,000.00 | $70,000,000.00 |

| Series B | 2011 | $117,000,000.00 | $1,300,000,000.00 |

| Series C | 2013 | $200,000.00 | $2,900,000,000.00 |

| Series D | 2014 | $519,700,000.00 | $10,500,000,000.00 |

| Series E | 2015 | $1,700,000,000.00 | $25,500,000,000.00 |

| Series F | 2016 | $1,000,000,000.00 | $31,000,000,000.00 |

Value dissemination

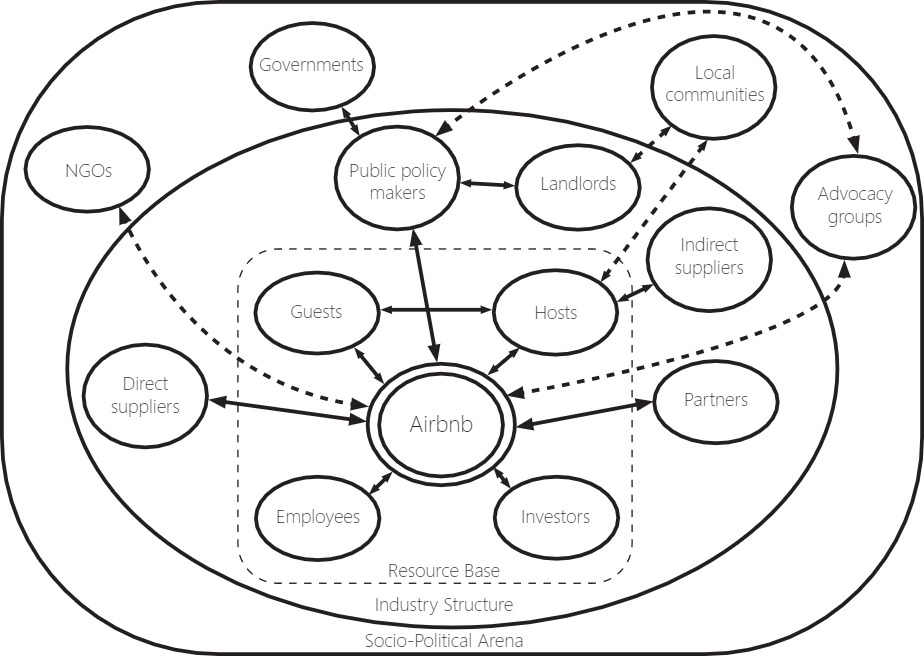

Airbnb cannot create value for its members and third parties without a large number of stakeholders. These stakeholders gain benefits from their association with Airbnb but also potentially incur risk or other negative effects resulting from peer-to-peer accommodation sharing – even without actively partaking in the economic activities surrounding Airbnb’s platform. It is in Airbnb’s interest to ensure that all key stakeholders continue to gain benefits to ensure that they will continue to assist Airbnb in creating value for hosts, guests and third parties. Using as a framework Post, Preston, and Sachs’ (2002) dimensions of strategic settings (which differentiates resource base, industry structure and socio-political context), Figure 2.4 paints a picture of Airbnb’s stakeholder relationships. We discuss the main relationships below in detail.

Dissemination to hosts

Hosts and guests are Airbnb’s core stakeholders. Hosts enable Airbnb to operate by making spaces available for rent. Without the hosts’ spaces, Airbnb has nothing to sell. The number, quality, and variety of listings on Airbnb.com determine how attractive Airbnb’s online trading platform is to guests (Dolnicar, 2018a). In addition to the core service of accommodation provision, hosts may also offer additional services to guests, including local insider tips about which attractions to visit and where to dine. The reviews hosts write about guests who stayed at their properties are invaluable to other hosts when they are assessing whether to grant permission to future guests to book (Karlsson et al., 2017). Many hosts further contribute to Airbnb.com through their involvement in host communities and in training new hosts and guests (e.g., Dolnicar 2018b).

The contribution from hosts comes at a risk. The most fundamental risk is that guests will not treat their property with respect and cause damage to it. Additional risks include tensions and disputes with neighbours or the body corporate (homeowners association) of an apartment complex. Hosts may also risk disputes, fines and lawsuits with government regulators if they are not in compliance with rules relating to short-term letting. Rules are not always unambiguous, creating a risky grey legal space within which hosts may need to operate (von Briel & Dolnicar, 2021a).

Because Airbnb relies on hosts, it is in its interest to minimise the risk for them of being active on the network. Airbnb achieves this in several ways: it enables people who otherwise would not be able to make space available for short-term rental to do so; it helps hosts to create an attractive listing; it assists with price setting; and it pays out a higher fraction of the price the guest pays than other online trading platforms or traditional tourism accommodation distribution channels. Airbnb also punishes guests who violate guest rules, including the possibility of legal proceedings and exclusion from the network. Despite substantial media interest in instances where Airbnb guests have caused severe damage to host properties in the first period, such instances are exceptionally rare: “of forty million guests staying on Airbnb in 2015, instances that resulted in more than $1,000 of damage occurred just 0.002% of the time” (Gallagher, 2017: 92).

Dissemination to guests

The second stakeholder group that is essential to Airbnb’s operations is its guests. Guests contribute to Airbnb by purchasing short-term access to space (making the trading platform more attractive to hosts), and by writing reviews about the properties they stayed at and their hosts. Reviews assist other guests in the decision-making process when they are looking for suitable accommodation. Reviews also serve as an inbuilt quality control mechanism, similar to the established market research practise of mystery shopping (Dolnicar, 2019). Guests can express their discontent or make constructive recommendations for improvement publicly, or in a private message to the hosts. For hosts who are motivated to improve the service they are offering, this process provides specific guidance on how they can achieve this.

Actively engaging with an online peer-to-peer accommodation trading platform is not risk-free. Guests could find themselves desperately searching for a property they booked that does not actually exist, or they could be disappointed in the space because it is much inferior to its appearance on the online listing. If the listing is a shared space, guests face several additional risks: the hosts could be disrespectful to their privacy, steal from them or physically harm them.

It is in Airbnb’s interest to minimise these risks to ensure that guests continue booking on Airbnb.com and write positive reviews which attract new guests to the network. Airbnb, therefore, put in place several risk mitigation measures benefitting guests, including a guarantee which entitles guests to alternative accommodation if the booked space does not exist or differs significantly from what was advertised. At the more fundamental level, Airbnb reduces risk by structuring the way peer-to-peer accommodation listings on Airbnb.com are presented. By structuring listings, hosts are nudged to comply with key safety requirements. Airbnb also manages financial transactions, giving guests confidence that delinquent hosts cannot take their money without providing access to space as agreed.

Dissemination to landlords and real estate developers

Hosts and guests as the key stakeholders of Airbnb have been discussed extensively in the literature (for a review see Dolnicar, 2019). Other stakeholders and their roles in Airbnb’s business model have received substantially less attention. These stakeholders include landlords and real estate developers.

Many landlords and real estate developers find themselves in the situation of being involved in the short-term rental business because their tenants list spaces owned by them on Airbnb. Their involvement with Airbnb is not intended and, in some instances, they may not even be aware of it. Despite this indirect and involuntary association with Airbnb, landlords and real estate agents can benefit from Airbnb and bear risk because of their association with Airbnb, giving them some bargaining power.

The risks landlords and real estate developers face are similar to those of hosts: the short-term nature of the rentals is likely to cause more damage and more wear than is the case with long-term rentals, the body corporate or owner’s association may object to short-term rental activity, neighbours may complain about reduced safety given that new sets of strangers are given access to the apartment complex on a regular basis, and the likelihood of neighbourhood complaints is higher. Accepting these risks allows real estate developers and landlords to benefit in several ways from their indirect association with Airbnb.

Airbnb is actively engaged in making apartment blocks more friendly to peer-to-peer accommodation trading. In collaboration with rental conglomerates, Airbnb has developed models under which tenants are given the right to sublet properties on Airbnb within the parameters set by the owners (Gallagher, 2017). One such initiative named Niido is discussed later in this chapter. As demand for Airbnb properties increases and apartment complexes become more peer-to-peer friendly, property value – in terms of both the sale and rental value – also increases, putting owners in the position of being able to charge higher rents because of the short-term rental return potential of a property: “landlords have already begun pricing the expectation of an Airbnb revenue stream into the rents they charge” (Gallagher, 2017: 204).

For property owners who are not happy for their long-term tenants to sublet their properties, Airbnb does not offer any solutions (McNamara, 2015) – owners are forced to find a solution within the framework of local tenancy laws. In the long term, the simplest option in such cases is to clarify in the rental agreement that subletting is not permissible.

Dissemination to local communities

Another of Airbnb’s key indirect stakeholders is the local community. Most of the public discourse in relation to Airbnb’s impact on the local community focuses on the negative externalities experienced by locals (for a review, see Dolnicar, 2019), including: competition for public resources upon which residents rely in their everyday lives, such as parking, guests’ lack of a sense of responsibility to care for the area and of accountability for their misbehaviour, and the nuisance of being stopped by tourists in residential areas and asked for directions or help (Edelman & Geradin, 2015).

In addition to these direct inconveniences to the lives of local residents, a large numbers of Airbnb listings at popular tourist destinations can also lead to an increase in real estate sale and rent prices. Airbnb put in place some measures to reduce the potential of disruption to the lives of locals, such as the neighbourhood support webpage (Airbnb, 2020c) where locals can complete a form stating the nature of the disruption. The complainant, after submitting the form, receives a confirmation, and Airbnb contacts the host (assuming the address provided by the complainant is an active listing hosting guests at that point in time). Airbnb reports back to the complainant at the end of this process.

Airbnb also put in place initiatives aimed at giving back to the communities that are potentially burdened by its operations. One such initiative in the first period was the co-design of 10% of its Airbnb Experience offererings with local non-profit organisations (Gallagher, 2017), donating all revenues to the participating non-profits.

While such initiatives are welcome, Airbnb does not take more radical action, such as limiting the number of listings to address social sustainability concerns (Ciulli & Kolk, 2019). This is largely the responsibility of local policy makers (von Briel & Dolnicar, 2020; 2021a). Overall, the bargaining power of locals is relatively low.

Dissemination to public policy makers

Public policy makers, including tax authorities, represent another key Airbnb stakeholder. They have substantial bargaining power because Airbnb is operating within their legislation. Airbnb is therefore highly motivated to lobby them and work with them to ensure it can run its operations as smoothly as possible. Regulations relating to short-term rentals vary substantially from location to location (Hajibaba & Dolnicar, 2018; von Briel & Dolnicar, 2021a), and have dramatically evolved over time within locations (von Briel & Dolnicar, 2020; 2021a). This is not surprising because the characteristics of a location affect the potential impact Airbnb has on it. Regional and remote areas in desperate need of revenue sources are likely to benefit more than popular city destinations struggling with overtourism. At city destinations popular with tourists, the negative externalities of Airbnb are most pronounced. This explains why the most restrictive government regulations have been implemented in such places, including New York, San Francisco, Paris and Barcelona. Airbnb has dedicated staff who lobby local government and aims to establish collaborative agreements with policy makers where possible. At some locations, Airbnb collects tourist taxes on behalf of hosts and forwards them directly to tax authorities – a matter that has become more salient in periods two and three.

Value development

Over the years, Airbnb has grown by continuously adding hosts and guests to its member base, which has substantially increased its valuation (The Economist, 2015, 2017). Acutely aware of its multi-sided platform business model and the importance of a large pool of hosts and guests to increase the attractiveness of the trading platform, Airbnb put in place several initiatives to ensure continued growth. At the host level, Airbnb established a referral program through which hosts can earn travel credits if they successfully recruit another host (Airbnb, 2020d). Airbnb also engages in acquisitions, especially in view of capturing new markets quickly and developing its offerings for specific segments. In 2016, Airbnb started cooperating with CWT Carlson Wagonlit Travel and American Express Global Business Travel in an attempt to expand from the leisure tourism market to the business market. While this growth occurred within Airbnb’s original business model, it represented a significant expansion geographically and with respect to the market segments Airbnb catered to.

In addition to strategic initiatives aimed at growth, Airbnb also benefits from cross-pollination: “when a traveler from France uses Airbnb in New York, he or she is more likely to go back to France and consider hosting, or to talk up the company to his or her friends, sparking awareness and ultimately leading to more listing activities in that market” (Gallagher, 2017: 40).

Experimenting with new growth paths (2017 ‒ 2019)

By 2016, Airbnb had laid the foundational core of its business model and established key relationships between the different sides of its accommodation sharing platform, propelling its growth. With these foundations established, the period between 2017 and 2019 was characterised by experimentation with different growth paths – some evolutionary, some revolutionary. Still, survey-based estimates in 2017 suggested that more than half of the travellers in Airbnb’s home market had never used Airbnb (Carty, 2017). The senior management team aspired to develop Airbnb into a “true ‘ecosystem’ or a ‘one-stop shop for travel’” (Ting, 2018b). These aspirations seem to have guided Airbnb’s expansionary course and built on the core of its business model. The following sections highlight critical changes to the elements of Airbnb’s business model.

Changes to the value proposition

Proposition to hosts

Between 2017 and 2019, Airbnb enhanced its value proposition for two specific kinds of hosts (Superhosts and hotels) as well as for the broader population of hosts. It addressed risks inherent to hosting guests by making the way monetary transactions are handled more convenient and competitive, and by increasing the value offered from its short-term property management solutions.

Identify suitable guests: Airbnb labels some of its host community as Superhosts (approximately 600,000 as of December 2018). Superhosts benefit from higher visibility and exposure in guest search queries on the platform and thus have a higher likelihood of receiving bookings (Ting, 2018c, 2018d). A second group of hosts that has received more attention in this second period are hotels listing rooms on the platform (Ting, 2018e). Airbnb enables hotels to find guests for their rooms on the platform via easy integration into their existing inventory management systems and without the need for a long-term contract. An example of developments in this area include new boutique aparthotel offerings providing long-term stay options for project-based travellers (Ting, 2018f).

Mitigating risk: Airbnb announced stricter moderation of its review systems to prevent guests from using negative reviews or ratings to petition hosts for discounts or other benefits (Schaal, 2019a). Airbnb support agents are granted the right to remove reviews that are irrelevant (e.g., based on features that have nothing to do with the host’s listing or that are beyond their control) or biased (e.g., based on host characteristics such as race or political orientation). They preclude guests from using the platform for repeated misconduct. These measures were accompanied by updates to Airbnb’s guest standards. The updates aim to protect hosts and host communities from issues such as littering in and outside of rental properties, parking violations, and open-invite parties or unauthorised guests (Whyte, 2019a).

By the end of September 2020, Airbnb had a network of more than 6,600 third-party partners in 25 locations to handle community support, alongside 24/7 assistance in Mandarin and English, and helplines and live chat in 8 to 11 languages during business hours. To prevent guest misconduct, Airbnb has also updated its reservation screening procedures – complementing computer screening with human judgement – to identify bookings from unauthorised parties and other potential misconduct (Sheivachman, 2019a). Airbnb still refrains from requiring government issued identification, in order to not discriminate access to its services on that basis. In January 2020, more than two thirds of accommodation transactions involved verified parties from the Airbnb guest and host community (Schaal, 2020a). Finally, Experience hosts must underwrite additional third-party insurance and prove possession of the required licences and permits to host government-sanctioned activities, for example, tours in national parks, or tours that involve high risk activities such as white water rafting (Schaal, 2019b).

Managing short-term rentals: Airbnb has started providing more support for professional hosting. Professional hosts are those that manage multiple properties that do not qualify as private, permanent residences. At the end of 2019, Airbnb reported that 10% of its hosts were non-individual hosts, and 28% of its overnight stays were booked with professional hosts (Schaal, 2020b). Small property managers with between two and twenty properties on Airbnb.com account for most of Airbnb’s listings. Professional hosts with more than 100 listings have seen the biggest growth overall (Schaal, 2020b). Functional value upgrades include IT integration with professional property management systems, calendars and booking management, pricing rules, additional messaging features (Ting, 2017a), and human support (Ting, 2018g). This is a valuable addition for hotels listing rooms on the platform (Ting, 2018a).

The relationship between property management companies acting as professional hosts and Airbnb remained challenging throughout this second period – particularly in holiday destination markets outside of urban centres. These companies disapprove of Airbnb’s short-term guest cancellation policy, which limits insurance policy sales. Professional hosts also present Airbnb with challenges in terms of collecting the taxes and other fees mandated by local regulations (e.g., overnight taxes and resort fees) and complying with local hosting caps (O’Neill, 2019a).

Handling monetary transactions: Alongside the payment options and support for monetary transactions introduced prior to 2017, Airbnb has started to open to local payment service providers such as WeChat Pay and Alipay in China (Schaal, 2019c). The way Airbnb handles monetary transactions and shares revenues has also been a sales argument in convincing hotels to list their rooms on Airbnb. Online travel agents charge hotels a commission rate of between 15% and 25% and do not offer additional services such as payment solutions or the collection and remission of taxes on behalf of the accommodation provider (Ting, 2018a). Airbnb charges much lower commission, allowing hotels to retain as much as 97% of the listed price. This is possible if Airbnb collects a part of its service fee from guests (Ting, 2018g) but does not seem attainable if hosts opt for the host-only charges model (Schaal, 2019d) – as we discuss under changes to value capture in period two.

Proposition to guests