3 The evolution of Airbnb’s competitive landscape

Dorine von Briel, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Sara Dolnicar, Department of Tourism, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Australia

Please cite as: von Briel, D. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) The evolution of Airbnb’s competitive landscape, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.) Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14195960

Airbnb’s competitive environment

Airbnb made the trading of space for short periods of time on a large scale possible through its online platform Airbnb.com. When Airbnb first entered the short-term accommodation market, the trading of space among ordinary people was not new, and established commercial accommodation providers were not overly concerned about the impact of Airbnb’s market entry on their businesses. Contrary to this assessment, Airbnb succeeded in attracting a substantial number of hosts and guests to its network in a remarkably short amount of time, making Airbnb.com an attractive marketplace for space trading among non-professional hosts (Reinhold & Dolnicar, 2018). Although space listed on Airbnb was initially booked primarily by a small niche segment of alternative travellers, its popularity increased quickly, leading to the widespread adoption of Airbnb’s booking platform by mainstream tourists all over the world. At this point, concerns about competition emerged (Zervas et al., 2017). Initially, these concerns were limited to established tourism accommodation providers at the lower end of the quality spectrum. As Airbnb’s popularity continued to increase, and demand for properties listed on Airbnb.com started to skyrocket, established tourism accommodation providers united and took collective action, objecting to what they perceived as unfair competition (Davidson & Infranca, 2018).

At the same time, the success of Airbnb attracted the attention of existing online travel agents, such as Booking.com, who saw an opportunity to expand their offerings. New start-up companies emerged, convinced they could reproduce Airbnb’s success by launching their own peer-to-peer accommodation platforms catering to the general travel market, or to a niche within the market such as gay travellers. This chapter discusses both these dimensions of competition – Airbnb’s competition with established, commercial tourism accommodation providers, and its competition with other peer-to-peer accommodation trading platform facilitators – and points to a blurring of competitive lines over time as Airbnb starts operating its own properties and established commercial tourism accommodation providers start using Airbnb as a distribution channel.

Competition between Airbnb and established tourism accommodation providers

Competition as perceived by established tourism accommodation providers

When Airbnb first started operating in San Francisco in 2008, the mainstream tourism accommodation sector was not overly concerned. Airbnb, after all, was catering to a niche market: people who were willing to sleep on an air mattress on the floor of someone’s living room. This small niche segment valued the personal connection with the host and living in an authentic neighbourhood, whereas hotel guests preferred facilities such as gyms and swimming pools and liked to stay at locations close to attractions (Belarmino et al., 2017).

These distinct differences in clientele made it easy, initially, for both Airbnb and hotel executives to play down the potential threat Airbnb posed to established businesses (Trenholm, 2015; DePillis, 2016; Business Insider Intelligence, 2017; Trejos, 2018). This strategy was not successful in the long term (Griswold, 2016; Ting, 2017; Dogru et al., 2019). As demand for Airbnb continued to grow, and it captured a larger share of the mass tourism market, the competitive relationship with hotels – especially lower-quality hotels – became evident. Tourists turned to Airbnb as a substitute for lower priced hotels. Airbnb started to encroach on the territory of mid-range hotels (Guttentag & Smith, 2017; Zervas et al., 2017; Hajibaba & Dolnicar, 2018a; Dogru et al., 2019). Substitution for hotels occurred especially during weekends and holidays (Sainaghi & Baggio, 2020), although a linear relationship between the number of Airbnb and hotel bookings could not be detected (Heo et al., 2019). From a tourist’s point of view, hotels and Airbnb were clearly perceived as competitive because Airbnb guests evaluated their Airbnb stay by comparing it to prior hotel experiences (Cheng & Jin, 2019).

The accommodation sector responded by publicly raising a range of concerns about Airbnb. The main argument was that regulations applied to the professional tourist accommodation sector did not extend to Airbnb’s operations (Benner, 2017; von Briel & Dolnicar, 2021). Complying with these regulations was associated with increased operating costs. For example, hotels have to regularly check all of their safety equipment (Staley, 2007; Guttentag, 2017; Dolnicar, 2019), and are required to ensure accessibility for tourists with special needs (Randle & Dolnicar, 2018; 2019; MacInnes et al., 2021). Initially, Airbnb hosts did not have to comply with any of these regulations, saving them money and potentially putting guest safety at risk. These savings enabled Airbnb hosts to sell short-term tourist accommodation at a lower price. Lower prices inevitably fuelled demand, leading to what hotels perceived as an unfair competitive position in the marketplace (Davidson & Infranca, 2018). Trade groups around the world took Airbnb to court, including the American Hotel and Lodging Association (Benner, 2017), the British Hospitality Association (Witts, 2016), the French Union for Hotel Professionals (Dicharry, 2019), and the Hotel Association of Canada (Press, 2018).

As discussed above, the focus of the established commercial accommodation sector appeared to be on fighting what it perceived as unfair competition, and demanding the modification of regulations. They did not focus much of their attention on understanding the key reasons that kept people from switching to Airbnb – their own unique selling propositions.

Competition as perceived by tourists

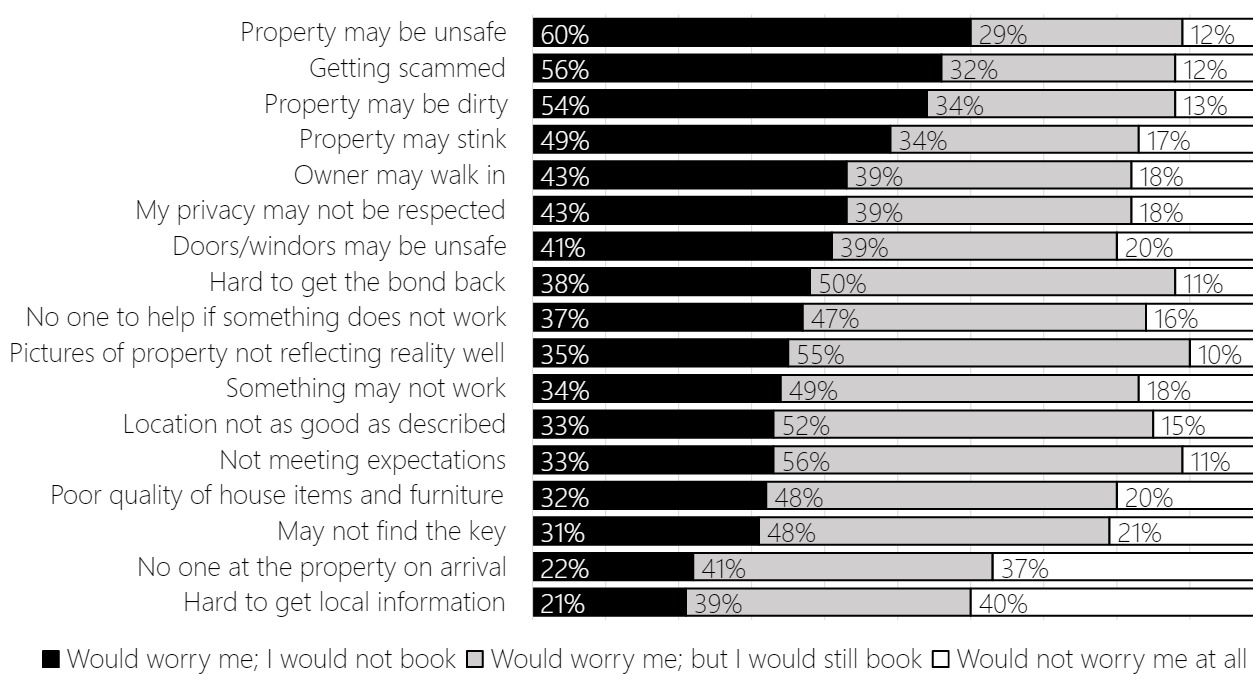

To gain insight into tourist perceptions of the competition between Airbnb and established accommodation providers, in 2017 we surveyed 668 adults who had been on holiday in the past 12 months. The sample contained 60% men; 59% living with a spouse/partner; 55% with children; and about a third employed full-time. Respondents indicated for each of 17 Airbnb-related concerns the extent to which they worry them. They had three response options for each concern: that it does not worry them at all, that it worries them but they would still book, or that it worries them so much that they would not book. Figure 3.1 shows the distribution of responses, which differ significantly across concerns (Friedman rank-sum test for repeated ordinal measures p-value=0).

The top concern in 2017 was property safety – 60% of respondents stated they would avoid using peer-to-peer accommodation for this reason. The perceived risk of doors and windows being unsafe would prevent 41% of respondents from booking on Airbnb. The following quote illustrates this concern: “I would not want to be staying in someone’s house if I know it is not safe. They could be a weird person. It could be a serial killer, could be a murderer.”

The second biggest concern was getting scammed, preventing 56% of respondents from using peer-to-peer accommodation. People were scared, for example, that a listed property may not exist at all. This concern stems from peer-to-peer accommodation network facilitators not owning the space, and not taking responsibility for online information accuracy.

About half of the respondents stated they would not use peer-to-peer accommodation because of concerns relating to cleanliness and smell. Lack of ownership and lack of maintenance carried out by the network facilitator may also play a role, as might lack of control over space improvement, accuracy of information, the unstandardised nature of the space and untrained hosts. Privacy concerns – which can result from untrained hosts – prevented 43% of respondents from booking on peer-to-peer networks.

Other concerns were worrisome enough to prevent at least a quarter of respondents from booking: not finding the key; hard to get local information; hard to get the bond back; no one at the property upon arrival; and no help if something does not work. These concerns stem from lack of on-site management, and untrained hosts. The following quote illustrates this: “I’ve had a few friends who […] were supposed to meet up with the host and get keys […] and the person was not there. They had really hard time contacting them.”

Finally, at least one third of tourists expressed concern that pictures on an online listing may not represent reality; that the location may not be as good as indicated; and that their expectations may not be met. More than a third of tourists worried that something may not work during their stay. About one third of respondents stated that they would not book on peer-to-peer networks because of concerns about poor quality furnishings.

Compared to established commercial accommodation providers, peer-to-peer networks are not involved in and have no control over the on-site management, quality, accuracy, maintenance, improvement and regulatory compliance of the spaces they sell, and do not offer service consistency or professionally trained hosts. These structural differences manifested very clearly in tourist concerns about booking through peer-to-peer networks in 2017 – a time, pre-COVID-19, when Airbnb was already established as a trading platform for peer-to peer accommodation. Safety was the primary concern at that time, followed by service quality, privacy and consistency. Tourists worried about unpleasant surprises and hosts not being helpful or responsive. Established providers reduce risks through standardisation and safety regulations, whereas peer-to-peer networks emphasise uniqueness, personalisation and customisation.

These findings confirm conclusions drawn in other studies that poor service, misleading information, the inability to control the quality of the service provided by hosts, and a lack of a guarantee that certain quality standards will be met are the main reasons that people choose not to return to another Airbnb property after having experienced one or a few of them (Huang et al., 2020). The importance of service quality provided decreases when guests rent the entire space, rather than a room only (Han & Yang, 2020). Findings also confirm that trust and safety concerns are common reasons preventing people from booking peer-to-peer accommodation (Chasin et al., 2018).

The leading peer-to-peer accommodation network facilitators have a good understanding of guest concerns, and continuously improve their systems to counteract perceptions of risk. To alleviate safety concerns, for example, Airbnb has created several tools over the years. The Airbnb website offers safety tips such as looking at host profiles and reviews before booking. The introduction of the Superhost status enabled guests to identify the most outstanding hosts. Airbnb also started featuring properties of particularly high quality under their Plus and Luxe programs. Airbnb Plus promises “a selection of only the highest quality homes with hosts known for great reviews and attention to detail […] verified through in-person quality inspection to ensure quality and design” (Airbnb, 2020a). Airbnb Luxe offers “extraordinary homes with five-star everything” (Airbnb, 2020b). Airbnb also introduced new safety measures in 2020, including a guest guarantee, a neighbour hotline and 100% property verification (Airbnb, 2019). Yet, the very nature of a peer-to-peer network structure means that the network cannot ever know with certainty whether promises are kept.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed tourists’ perspectives on the trustworthiness and safety of peer-to-peer accommodation. Tourists appear to be trusting peer-to-peer accommodation more than hotels, despite hotels having higher hygiene standards (Oliver, 2020). A possible explanation for this perception is that staying at a peer-to-peer traded space does not involve sharing space with many other tourists (Oliver, 2020). This may be the reason that Airbnb is recovering from COVID-19-induced hibernation faster than hotels (Press, 2020).

Competition between Airbnb and other peer-to-peer accommodation networks

Network facilitators around the world

Table 3.1 contains a comprehensive list of peer-to-peer accommodation platform facilitators, along with publicly available information such as the location of the head office, the year of establishment, and the number of countries covered by the network. Table 3.1 is based on the list developed by Hajibaba and Dolnicar (2018b), which integrated data from JustPark (2020) and Crunchbase (2020). We expanded the table by including new facilitators, and facilitators that have failed. Facilitators that failed include Roomorama and chillWRKR. When facilitators stop operating, they typically do not provide the reasons why.

Table 3.1 does not include facilitators in China (they are discussed separately in chapter 7: Xiang et al., 2021), or facilitators that have transformed their businesses from peer-to-peer accommodation trading to something else (Flatclub and Innclusive, for example, developed into providers of corporate rentals and services; Yudan, 2020).

|

Name |

Headquarters |

Started |

Guest fee |

Host Fee |

Listings |

Countries |

Niche market |

|

9flats |

Singapore |

2010 |

Commission |

Commission |

200,000 |

190 |

No |

|

Accessible Accommodation |

Australia |

2017 |

|

122 |

3 |

Disability |

|

|

Airbnb |

San Francisco (US) |

2008 |

Fee |

Commission |

7 million |

195 |

No |

|

AURA |

Sydney (Australia) |

2009 |

Free |

Commission |

13,000 |

1 |

No |

|

Bancha |

Rome (Italy) |

2012 |

Fee |

Closed down in 2015 |

|||

|

beWelcome |

Renne (France) |

2007 |

Free |

Free |

6,400 |

195 |

Cooperation (non-profit) |

|

Booking.com |

Amsterdam (Netherlands) |

1996 |

Free |

Commission |

5 million |

195 |

No |

|

Bring Fido |

Greenville (US) |

2004 |

Free |

Commission |

77,676 |

100 |

Dog Friendly |

|

Camplify |

Newcastle (Australia) |

2014 |

Fee |

Commission |

5,000 |

1 |

Campers |

|

CasaVersa |

Tel Aviv (Israel) |

2012 |

Home exchange |

Closed down in 2018 |

|||

|

chillWRKR |

New York (US) |

|

Fee |

Closed down in 2016 |

|||

|

Couchsurfing |

San Francisco (US) |

2004 |

Fee |

Fee |

15.9 million |

195 |

No |

|

Disability Housing |

Australia |

2017 |

|

|

172 |

1 |

Disability |

|

Disable Holidays |

UK |

2001 |

|

|

|

35 |

Disability |

|

Fairbnb.coop. |

Bologna (Italy) |

2016 |

|

Commission |

83 |

4 |

Cooperation |

|

Ferienhaus-Privat |

Germany |

1998 |

Commission |

Commission |

984 |

45 |

No |

|

Ferienhausmiete (Tourist Paradise) |

Berlin (Germany) |

2004 |

|

Fee |

100,000 |

190 |

No |

|

FlipKey (TripAdvisor) |

Boston (US) |

2007 |

Commission |

Commission or fee |

300,000 |

190 |

No |

|

Gay Homestays |

Manchester (UK) |

2010 |

Fee |

Commission |

2,720 |

103 |

Gay |

|

GoCambio |

Youhal (Ireland) |

2014 |

Free |

Closed down in 2016 |

|||

|

Hanintel |

Seoul (Korea) |

2009 |

Free |

Commission |

400 |

30 |

No |

|

Holiday Lettings (TripAdvisor) |

Oxford (UK) |

1999 |

Commission |

Commission |

400,000 |

150 |

No |

|

HomeAway (Expedia Group) |

Texas (US) |

2005 |

Commission |

Commission or fee |

2.3 million |

190 |

No |

|

HomeExchange |

Boston (US) |

1992 |

Home exchange |

Annual fee |

400,000 |

187 |

No |

|

Homestay |

Dublin (Ireland) |

2013 |

Free |

Commission |

55,000 |

160 |

No |

|

Horizon |

Seattle (US) |

2014 |

Free (guests can make a donation) |

Closed down in 2020 |

|||

|

HouseTrip (TripAdvisor) |

Lausanne (Switzerland) |

2009 |

Commission |

Commission |

300,000 |

160 |

No |

|

Kozaza |

Seoul (Korea) |

2012 |

Fee |

Commission |

5,000 |

1 |

No |

|

Krash |

Boston (US) |

2012 |

Fee |

Closed down in 2016 |

|||

|

LoveHOmeSwap |

London, England |

2011 |

Home exchange |

Annual fee |

20,000 |

100+ |

No |

|

Magpie App |

San Francisco US) |

2007 |

Home exchange |

Closed down in 2017 |

|||

|

Matching Houses |

Cornwall (UK) |

2009 |

Home Exchange |

Home Exchange |

76 |

9 |

Disability |

|

MatchPad |

New York (US) |

2014 |

Fee |

Closed down in 2016 |

|||

|

Meshtrip |

San Francisco US) |

2014 |

Fee |

Closed down in 2016 |

|||

|

misterb&b |

San Francisco (US) |

2013 |

Commission |

Commission |

310,000 |

135 |

Gay |

|

MyTwinPlace |

Barcelona (Spain) |

2012 |

Home exchange |

Closed down in 2017 |

|||

|

Niumba (Trip Advisor) |

Madrid (Spain) |

2005 |

Commission |

Commission |

100,000 |

71 |

No |

|

Noirbnb |

Miami (US) |

2015 |

Fee |

Commission |

|

|

Persons of colour |

|

Oasis (Accor) |

Miami (US) |

2009 |

Fee |

Commission |

1,500 |

13 |

Luxury |

|

onefinestay (Accor) |

London (UK) |

2009 |

Fee |

Commission |

10,000 |

4 |

Luxury |

|

Oyo Rooms |

New Delhi (India) |

2013 |

Fee |

|

130,000 |

80 |

No |

|

OYO Vacation home (@leisure) |

Amsterdam (Netherlands) |

2014 |

|

|

140,000 |

70 |

No |

|

People Like us |

Sydney (Australia) |

2018 |

Free |

Free |

3,375 |

|

Cooperation |

|

Perfect Experiences (Paris Perfect) |

Paris (France) |

1999 |

|

|

242 |

4 |

Luxury |

|

Red Awning (Perfect Places) |

Los Altos (US) |

1996 |

Free |

Commission |

100,000 |

103 |

No |

|

Rent Like A Champion |

Chicago (US) |

2005 |

Commission |

Fee |

3,000 |

1 |

Team and sporting events |

|

Rentini |

New York (US) |

2007 |

Fee |

Closed down in 2015 |

|||

|

Roomorama |

New York (US) |

2008 |

Fee |

Closed down in 2017 |

|||

|

Sabbatical Homes |

Manhattan Beach (US) |

2000 |

Fee (free for academics) |

Fee |

4,425 |

56 |

Academics |

|

SleepOut |

Mauritius |

2012 |

Fee |

Commission |

6,000 |

60 |

No |

|

Sonder (formerly Flatbook) |

San Francisco (US) |

2012 |

Fee |

Commission |

5,000 |

7 |

No |

|

Stay Square |

Perth (Australia) |

|

Fee |

Closed down in 2015 |

|||

|

Swap and Surf |

France |

|

Home exchange |

Closed down in 2015 |

|||

|

TalkTalkbnb |

Lorient (France) |

2016 |

Free |

|

1,602 |

195 |

Language |

|

Traum-Ferienwohnungen |

Bremen (Germany) |

2001 |

Fee |

Commission |

100,000 |

70 |

No |

|

TripAdvisor Holiday rental |

|

2009 |

Commission |

Commission |

842,000 |

195 |

No |

|

Turstroots |

United Kingdom |

2015 |

Free |

Free |

10,000 |

|

Cooperation (non-profit) |

|

Vacation Home Rentals (Trip Advisor) |

Boston (US) |

2004 |

Commission |

Commission |

100,000 |

190 |

No |

|

VBRO (Home Away) |

Austin (US) |

1995 |

Fee |

Commission |

2 million |

190 |

No |

|

Warm Showers |

Colorado, (US) |

2010 |

Donations |

Home Exchange |

93,000 |

161 |

Cyclists |

|

Wimbify |

San Francisco (US) |

2015 |

Trading in virtual credits |

Closed down in 2018 |

|||

|

Wimdu |

Berlin (Germany) |

2011 |

Commission |

Commission |

350,000 |

150 |

No |

Table 3.1: Facilitators of peer-to-peer accommodation platforms (in alphabetical order, blank cells indicate that data for the platform could not be identified)

Most facilitators charge commission, a fixed or one-off annual fee to hosts, or a combination of these fees. Even Couchsurfing – the pioneer of free space-sharing among ordinary people – converted to a paid service in May 2020 (Couchsurfing, 2020). Couchsurfing explains that a fee had to be introduced to ensure the viability of the online trading platform it provided. The platform had historically been funded by donations and advertising. COVID-19 led to a reduction in donations from 4% to 0% and a significant reduction in advertising revenue. This change introduced by Couchsurfing aligns its business model with facilitators such as Home Exchange, Flipkey and Love Home Swap. All of them charge a service fee, although guests do not pay hosts for access to space; they exchange space for space instead. After the announcement from Couchsurfing, other platforms with a non-profit or free model such as People Like Us revealed their intention to charge a small fee to their members (Seitam, 2020). Only a few continue to offer facilitation services on their online platforms for free, including be Welcome and Turstroots.

Of the 47 active facilitators of online short-term rental trading platforms, 20 target niche markets. Specialisation has emerged as one of the characteristics of successful facilitators (Kavadias et al., 2016). Specialised platform facilitators cater to the needs of very specific consumer segments who have either been ignored by bigger platform facilitators or have experienced discrimination or safety concerns when using mainstream peer-to-peer network platforms. Successful niche providers include Noirbnb (catering to people of colour), misterb&b and Gay Homestay (for gay users), Matching Houses, Disable Holidays and Accessible Accommodation (for people with disabilities), Rent Like a Champion (for university football players), and Warm Showers (for touring cyclists). These niche providers are surviving in the competitive peer-to-peer accommodation trading market despite their comparably small size.

One development that helps smaller facilitators survive and grow is the emergence of a new type of search engine. Tripping.com and Hometogo.com aggregate listings across all peer-to-peer accommodation network platforms. They are transformational in the peer-to-peer trading market because they enable guests to search for short-term rentals across all platforms, with the platform only becoming visible when the guest clicks on it. These new search engines reduce the pressure on smaller facilitators to quickly and simultaneously grow supply and demand – a key success criterion for multi-sided platform businesses (Reinhold & Dolnicar, 2018; 2021). Being featured on these new search engines allows niche providers to continue offering a highly specialised service while still being discoverable by the mass market. With a similar strategy in mind, the platform Red Awning negotiated to be integrated in the hotel search engine Trivago (Stevens, 2019).

To assess the competitive landscape in 2021, we surveyed peer-to-peer accommodation users in January. We conducted two separate surveys, one with 57 Airbnb hosts and the other with 102 Airbnb guests residing in Australia, New Zealand, the US, the UK and Canada. Participants must have booked or listed accommodation on Airbnb in the last 24 months to meet the eligibility requirements of the survey.

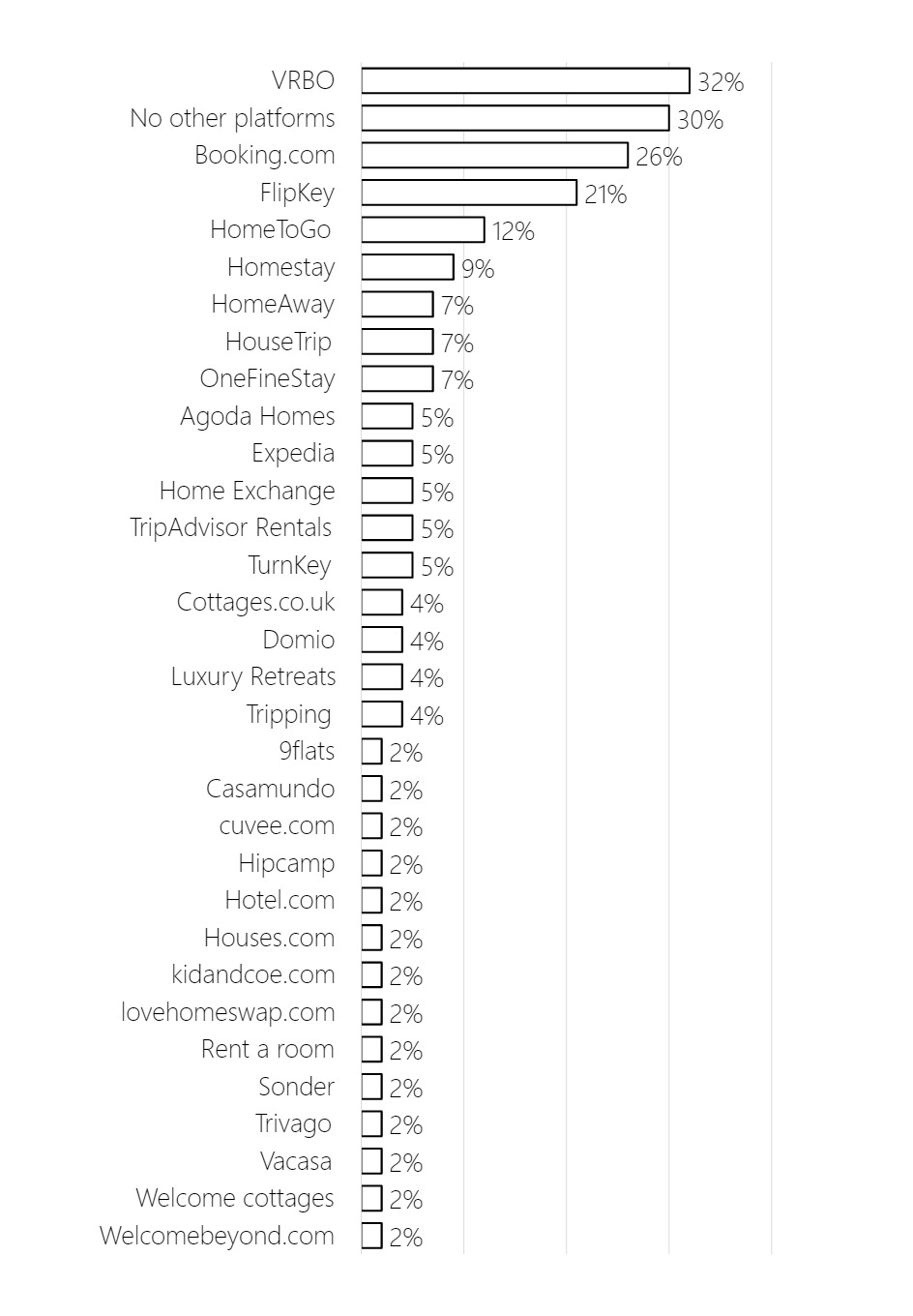

We asked hosts to list –without any assistance – whether they were aware of any online peer-to-peer accommodation trading platforms other than Airbnb. Hosts were able to list up to five other platforms. Figure 3.2 contains the responses. Approximately one third of respondents were unable to list any other trading platform, another third listed VRBO, and 26% named Booking.com. Flipkey was listed by 21% of respondents, there is then a substantial drop to 12% for HomeToGo.

The unaided responses shown in Figure 3.2 also illustrate that – from a host’s perspective – it is irrelevant whether a trading platform specialises in peer-to-peer accommodation or is a commercial online travel agency, especially given that the boundaries between the two have blurred over the years. For example, the website Hotel.com is now offering the option for private hosts to list their property on its platform.

We also asked hosts to name their favourite platform. Not surprisingly – given the requirement to be listed on Airbnb to be able to complete the survey – more than 85% of respondents indicated that their preferred platform was Airbnb.com. In second place was Booking.com (7%). Surprisingly, 4% of respondents mentioned Facebook, making it the third choice on the list. The social media platform allows the listing of short-term rentals on its Marketplace and despite not being a peer-to-peer accommodation platform, provides great visibility to listings due to the high number of members on its social media platform. This finding illustrates the importance hosts give to reaching high numbers of potential guests.

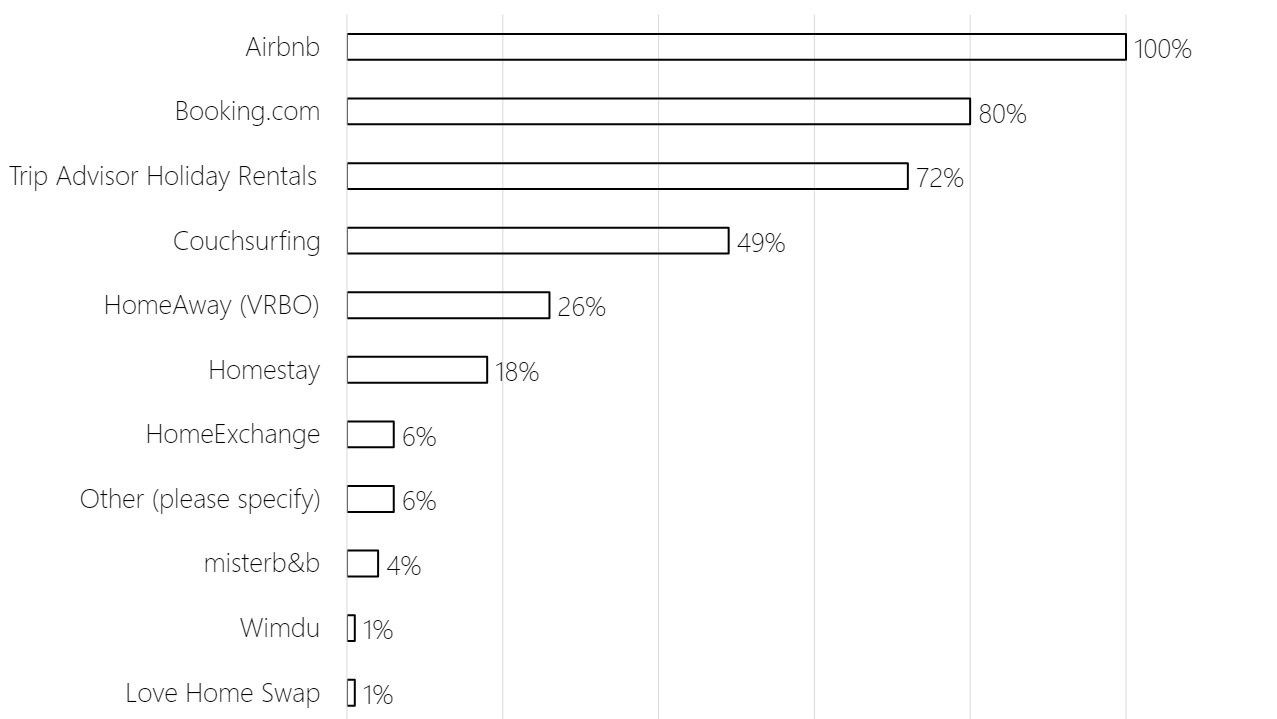

We also asked people who had booked accommodation on Airbnb which their favourite online trading platform was. Again, unsurprisingly, 80% name Airbnb.com, followed by Booking.com (5%), Expedia (2%) and Homeaway (2%). We also provided guests with a list of the ten biggest peer-to-peer accommodation platform facilitators and asked them which ones they were familiar with. Figure 3.3 contains the results.

Given that all respondents were Airbnb guests, all of them recognised Airbnb. A vast majority of guests also recognised Booking.com (80%) and Trip Advisor Holiday Rental (72%). Nearly half of all respondents identified Couchsurfing (49%). The remaining peer-to-peer accommodation providers were recognised by less than a third of the Airbnb guests we surveyed, including VRBO (26%), Homestay (18%) and niche providers such as misterb&B (4%),

Success factors of platform facilitators

The best predictor of success for a platform facilitator is its capacity to attract large numbers of hosts and guests (Reinhold & Dolnicar, 2018; Reinhold & Dolnicar, 2021; Dolnicar, 2019). Paid online peer-to-peer accommodation platform facilitators that become successful manage to increase their stock rapidly (Zervas et al., 2017), sometimes relying on acquisitions. Table 3.2 provides a summary of acquisitions in the peer-to-peer accommodation market.

| Company | Acquisitions |

|---|---|

| 9flats | iStopOver (2012) |

| Accor | onefinestay (2016). Oasis (2016) – 30% shares |

| Airbnb | Accoleo (2011), Crashpadder (2012). Luxuty Retreats (2017). Accomable (2017). Trooly (2017), Gaest (2019), Hotel Tonight (2019), Urbandoor (2019) |

| Booking.com | Buuteeq (2014). Hotel Ninjas (2014). Rocketmiles (2015). Evature (2017) |

| Home Away Acquired by Expedia in 2015 |

Cyber Rentals (2005), Great Rentals (2005), A1 Vacations (2005), TripHomes (2005), HomeAway.co.uk (2005), FeWodirekt.de (2005). Vbro (2006). Abritel (2007). Vacation Rentals (2007), Owners Direct (2007), Homelidays (2009), BedandBreakfast (2010). Alugue Temporada (2010). Instant Software (2010), Escapia (2010), RealHolidays (2011), Toprural (2012), Travelmob (2013), Stayz Australia (2013), Bookabach (2013). Glad to Have You (2014), Dwellable (2015). Pillow (2018). Apartment Jet (2018). CanadaStays (2019) |

| HomeExchange Acquired by Tukkazzal in 2017 |

Knok (2016), Trampolinn (2016). Night Swapping (2019) |

| Trip Advisor Holiday Rental | Flipkey (2008), Holiday Lettings (2010). Niumba (2013), Vacation Home Rentals (2014), House Trip (2016) |

| Red Awning | Perfect Places (2015) |

The need for rapid growth of demand and supply on the trading platform leads to a small number of facilitators having a major competitive advantage. Couchsurfing, for example, has 12 million members all around the world. Airbnb, Booking.com, and HomeAway lead the paid peer-to-peer accommodation market with seven, five and two million listings, trading in 190, 227, and 160 countries respectively. From 2015 to 2018, Airbnb’s revenue increased by 10% (Dogru et al., 2020). The tourist accommodation market share in the United States held by hotels was 94% in 2013. By 2018, hotel market share had dropped to 70%, with Airbnb increasing its share to 19% and HomeAway to 11% (Gessner, 2019).

Large platform facilitators have been proactive in the acquisition of smaller businesses. Airbnb’s acquisition strategy is driven by three factors: bringing new technologies to Airbnb; entering a local market; and entering a niche market (Sonnemaker, 2020). About half of Airbnb’s acquisitions were motivated by technological innovation. Trooly, for example, conducted complete background checks on users, including investigating their activities on the dark web. Other acquisitions enabled Airbnb to enter new markets. The purchase of Accoleo, for example, strengthened its position in Germany. The purchase of Accomable in 2017 allowed Airbnb to counteract accusations that it was failing to cater to guests with disabilities (Randle & Dolnicar, 2018).

Booking.com completed four acquisitions. It purchased Buuteeq and Hotel Ninjas in 2014, Rocketmiles in 2015 and Evature in 2017. Booking.com itself was bought by Priceline in 2012, expanding its existing portfolio of hotels on ActiveHotels.com. Instantly, the number of agreements with hotels jumped from 10,000 to 100,000 (O’Neil, 2020). Today, Booking.com includes: two online travel agencies named KAYAK and FareHarbour; an online travel agency specialising in North America (Priceline); meta search engines for hotels (HotelsCombined), flights (Cheapflights), and general travel (Momondo and Mundi); and an online travel agency specialising in the Asia-Pacific region (Agoda); Rentalcars.com; a software company for restaurants (Venga Inc); and OpenTable, which facilitates restaurant bookings (Prieto, 2020).

HomeAway has been the most proactive in expanding its operations through acquisitions (22 since 2005). Expedia purchased HomeAway in 2015, at a time when Expedia’s portfolio already included Hotels.com, Hotwire.com and Trivago. Expedia also purchased Travelocity in 2015. The group decided to retain the HomeAway brand name, and continued to add to it by purchasing Pillow, Apartment Jet and Canada Stay. TripAdvisor is a spin-off company of the Expedia Group holding. It acquired Vacation Home Rental, Holiday Lettings, Niumba, HouseTrip, and FlipKey. In March 2020, TripAdvisor put its collection of rental platforms up for sale (Schaal, 2020).

The evolution of HomeExchange is similar to that of the other big platform facilitators. The company only made two acquisitions before it was bought by Tukkazza! in 2017. With Tukkazza! having already purchased Guest to Guest, the three brands combined instantly created the biggest market for home exchange in the world with 400,000 homes.

Not all successful short-term rental platforms started as peer-to-peer accommodation facilitators. Booking.com was a traditional online distributor of hotels that benefitted, almost accidentally, from the Airbnb boom. By 2017, Booking.com held 65.5% of the market share of all European online travel agencies. By 2018, it held 41% of the world’s market share (Prieto, 2020). Booking.com is the global leader in the online travel agency market. Its market capitalisation reached $88 million in 2019, when it was described as “the most profitable travel deal of the century” (O’Neil, 2020; Wintermaier, 2020). Similarly, HomeAway initially started with the trading of holiday rentals. Listings on these two platforms are not limited to peer-to-peer accommodation. Their origins gave them a competitive advantage because they listed a wide range of properties, and, as a consequence, attracted many tourists looking for accommodation to their online platform.

A transformed market

Changes to market entry conditions

Success among platform facilitators varies; only 43 have succeeded and 209 have failed (Cusumano et al., 2020). Poor pricing strategies, failing to attract hosts or guests, having to subsidise hosts or guests, and entering the market too late are common mistakes unsuccessful facilitators made (Cusumano et al., 2020). A lack of new members, insufficient market knowledge and trust and safety concerns also caused the failure of many start-ups (Chasin et al., 2018). These challenges make the market opaque to new players, which may account for the lack of new peer-to-peer accommodation platforms created recently – only two in 2017 and one in 2018. Between 2015 and 2018, 15 platform facilitators had to close down and many more have been acquired. The industry has entered a new stage of maturity and the current players are not start-ups anymore; they are big established multinational conglomerates.

The reaction of users to this transformation is not homogenous. Some guests and hosts prefer to book on smaller platforms, engaging exclusively in peer-to-peer trading among ordinary people. Cooperative peer-to-peer accommodation platforms cater to these consumers. Cooperatives are particularly successful in European cities, which have suffered negative externalities due to overtourism. Les Oiseaux de Passage, for instance, was founded in Marseille (France) in 2014. Fairbnb started in Bologna (Italy) in 2016. For users, the business model of cooperatives represents true trading among peers (Petruzzi, 2021).

Changes in the nature of transactions on peer-to-peer accommodation trading platforms

In the decade following Airbnb’s launch, the peer-to-peer accommodation sector experienced a complete transformation. Hotels appeared on peer-to-peer accommodation network platforms, and platform facilitators started acting like travel agents and hotels, blurring the lines of who is offering which service to tourists. In the past, peer-to-peer accommodation hosts were deliberately positioned as not being industry professionals (Dolnicar, 2019). Today’s platforms display a more professionalised picture (Deboosere et al., 2019). In the most popular Airbnb cities, 15% of hosts owned 38% of listings and accounted for 45% of all bookings (Slee, 2014). Similarly, in New York City, 2% of hosts generated 24% of the total Airbnb revenue (Popper, 2015).

Not only did the nature of accommodation listings change, but Airbnb also started to trade experiences (Aversa et al., 2017; Gardiner & Dolnicar, 2018; 2021) and to actively pursue the business traveller market. Pre–COVID-19 business travellers stayed longer; 10.5 days compared to 6.8 for leisure tourists. Business travellers also booked earlier (Coop, 2016). In 2017, Airbnb invested heavily in launching its business stay operations. Investments included buildings in San Francisco; the website Urbandoor; the app Hotel Tonight; as well as the rental service Gaest (Burke, 2019). In 2019, Airbnb partnered with RXR Realty to convert ten floors of 75 Rockefeller Plaza in Manhattan into 200 apartment-style properties, including a private social club, business centre, meeting and events spaces, co–working areas and common areas. Offering similar amenities as hotels, these properties would be available exclusively on Airbnb, via both the regular platform and a new one named Airbnb for Work (Airoldi, 2020). Airbnb also invested $160 million into Lyric, a business travel start-up offering premium service apartments. Amenities include hotel-quality cleaning services and 24-hour online support (Abril, 2020).

In response, established hotel chains, such as Accor and Marriott, pushed the online distribution of their accommodation offerings, making them accessible to the prolific users of peer-to-peer accommodation. Accor started implementing this strategy with the acquisition of onefinestay (UK) and Oasis (Miami) as early as 2016. Marriott launched its Home Sharing pilot – now called Homes & Villas – in London in 2018, later expanding into Paris, Rome and Lisbon. Marriott partners with property managers, independent hotels and operators to offer 2,000 spaces in 100 destinations. Bookings are available on the Marriott and Homes & Villas websites, through an app, and through specialised travel agents. To differentiate themselves from Airbnb and to utilise their expertise, hotel chains focus on the luxury niche. The Vice President of Homes & Villas by Marriott International, Jennifer Hsieh, declared “By working with a select group of professional management companies that understand and operate in this dynamic landscape, we are able to focus on what we do best – selecting a breadth of homes in inspiring destinations, setting standards for responsive service and designing a seamless booking experience that helps our guests navigate an increasingly complex and uncertain set of home rental choices” (Dickey, 2019).

The effect of COVID-19

COVID-19 had terrible repercussions for the tourism industry because of lockdowns and extended travel bans all over the world. Airbnb estimated their loss at US $1 billion (Crane, 2020; Fleetwood, 2020). Other platforms have not declared their pandemic-induced financial losses. Some reported drops in bookings: Booking.com lost 84% of its bookings and Expedia 82% (The Economist, 2020). Surprisingly, despite these adverse circumstances, only one of the platform facilitators listed in Table 3.1 closed down. Horizon, a facilitator based in Seattle, worked with community organisations and its hosts and guests to fight homelessness. The company posted a message on its website in the first half of 2020 explaining that they had to close down due to lack of funding.

When borders reopened, the market was completely transformed (Dolnicar & Zare, 2020). Hosts shifted from the short-term to the long-term rental market. Guests wanted to travel as a family, by car, and to low density areas (Chang, 2020; Transparent, 2020). Airbnb’s CEO announced a complete change of strategy for the company’s future, pledging to support smaller (non-professional) hosts and consider Airbnb’s impact on cities and communities (Crane, 2020). In contrast to its 2019 strategy, Airbnb’s CEO also announced a complete withdrawal from the business travel market (Chang, 2020).

Conclusions

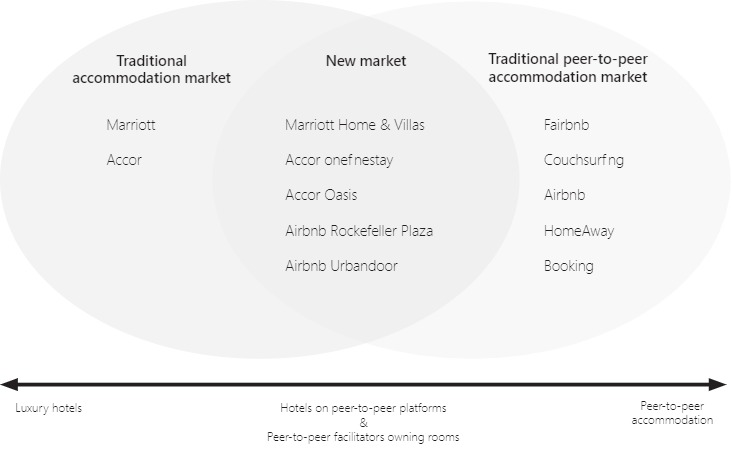

When Airbnb launched in 2008, it introduced a new model for the provision of short term accommodation. Peer-to-peer accommodation facilitators such as Airbnb did not own or have leases for the spaces they were trading, and ultimately had no control over whether the host would provide the space as it was listed and described on Airbnb.com. Tourists initially perceived the model as risky, but uptake increased because Airbnb listings tended to be more affordable than equivalent accommodation offerings from professional, licensed accommodation providers. Figure 3.4 illustrates how these two markets were initially positioned at opposite ends of the service spectrum.

Over the years, the lines between high-end hotel chains and peer-to-peer accommodation facilitators have blurred and a new market has emerged. Airbnb modified its business model by investing in real estate and offering hotel-like accommodation and services (e.g. Airbnb Rockefeller Plaza, Airbnb Urbandoor). Hotels – determined to fight for their market share under the changed market conditions – created accommodation offerings inspired by the peer-to-peer space trading model (e.g. Marriott Home & Villas, Accor onefinestay, Accor Oasis).

In the midst of those changes, COVID-19 disrupted the entire tourism industry and forced many accommodation providers to rethink their business model. Airbnb CEO, Brian Chesky, reflected: “We grew so fast, we made mistakes. We drifted. We really need to think through our impact on cities and communities” (Crane, 2020). Chesky announced that the new Airbnb strategy will consist of stepping back from the new market and returning back to its origins. If this does indeed occur, the differences between hotels and peer-to-peer traded spaces may become clearer again as a consequence. Hotels are recovering from COVID-19 more slowly than Airbnb. They may, as a consequence of this experience, continue to pursue new avenues of accommodation provision that resemble the peer-to-peer format.

Acknowledgements

This chapter is based on Hajibaba, H. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Chapter 6 – Airbnb and its Competitors, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 63–76.

Survey data collection in 2021 was approved by the University of Queensland Human Ethics Committee (approval number 2020001659).

References

Abril, D. (2020) Airbnb leads $160 million investment in startup designing apartments for travelers, retrieved on November 12, 2020 from https://fortune.com/2019/04/17/airbnb-invests-in-lyric

Airbnb (2019) In the business of trust, retrieved on July 13, 2020 from https://news.airbnb.com/in-the-business-of-trust

Airbnb (2020a) Introducing plus, retrieved on November 12, 2020 from https://www.airbnb.com.au/plus

Airbnb (2020b) Extraordinary homes with five-star everything, retrieved on November 12, 2020 from https://www.airbnb.com.au/s/luxury

Airoldi, D.M. (2020) Airbnb moves on business travellers, Marriott moves on Airbnb & upstart competitor raises $100m, retrieved on November 12, 2020 from https://www.proquest.com/docview/2241220120/AA9105F29AF74A9EPQ/1

Aversa, P., Haefliger, S. and Reza, D.G. (2017) Building a winning business model portfolio, MIT Sloan Management Review, 58(4), 49-54.

Belarmino, A., Whalen, E., Koh, Y. and Bowen, J.T. (2017) Comparing guests’ key attributes of peer-to-peer accommodations and hotels: mixed-methods approach, Current Issues in Tourism, 22(1), 1-7.

Benner, K. (2017) Inside the hotel industry’s plan to combat Airbnb, retrieved on July 13, 2017 from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/16/technology/inside-the-hotel-industrys-plan-to-combat-airbnb.html

Burke, K. (2019) S.F. officials look to regulate city’s burgeoning extended-stay rental market, retrieved on June 27, 2020 from https://www.bizjournals.com/sanfrancisco/news/2019/10/24/extended-stay-rental-sf-regulate-airbnb-sonder.html

Business Insider Intelligence (2017) Airbnb CEO speaks on disrupting hotel industry, retrieved on August 03, 2017 from www.businessinsider.com/airbnb-ceo-speaks-on-disrupting-hotel-industry-2017-3

Chang, E. (2020) Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky on ‘Bloomberg Studio 1.0’, retrieved on July 13, 2020 from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2020-07-10/airbnb-ceo-brian-chesky-on-bloomberg-studio-1-0-video

Chasin, F., von Hoffen, M., Hoffmeister, B. and Becker, J. (2018) Reasons for failures of sharing economy businesses, MIS Quarterly Executive, 17(3), 185-199.

Cheng, M. and Jin, X. (2019) What do Airbnb users care about? An analysis of online review comments, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 58-70.

Coop, H. (2016) Homestay.com sees rise in demand from business travel sector, retrieved on May 5, 2020 from www.homestay.com/press/2016/01/27/homestay-com-sees-rise-in-demand-from-business-travel-sector

Couchsurfing (2020) We hear you, retrieved on October 10, 2020 from https://blog.couchsurfing.com/we-hear-you

Crane, E. (2020) Airbnb’s founder estimates they’ve lost $1 billion during the COVID-19 pandemic as it’s revealed the company plans to confidentially file for IPO this month, retrieved on October 10, 2020 from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8617085/Airbnbs-founder-estimates-theyve-lost-1billion-covid.html

Crunchbase (2020) Discover innovative companies and the people behind them, retrieved on October 10, 2020 from https://www.crunchbase.com

Cusumano, M., Yoffie, D. and Gawer, A. (2020) The future of platforms, MIT Sloan Management Review, 61(3), 46-54.

Davidson, N. and Infranca, J. (2018) The place of the sharing economy, in N. Davidson, M. Finck, and J. Infranca (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of the Law of the Sharing Economy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 205-219.

Deboosere, R., Kerrigan, D.J., Wachsmuth, D. and El-Geneidy, A. (2019) Location, location and professionalization: a multilevel hedonic analysis of Airbnb listing prices and revenue, Regional Studies, Regional Science, 6(1), 143-156.

DePillis, L. (2016) Hotels don’t actually appear to be that scared of Airbnb yet, retrieved on August 3, 2020 from www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/02/26/hotels- dont-actually-appear-to-be-that-scared-of-airbnb-yet

Dicharry, E. (2019) Airbnb remporte une victoire devant la justice européenne, retrieved on May 21, 2020 from https://www.lesechos.fr/industrie-services/tourisme-transport/airbnb-remporte-une-victoire-clef-face-a-la-france-devant-la-justice-europeenne-1157783

Dickey, M.R. (2019) Marriott is launching a home-sharing product in the US, retrieved on May 21, 2020 from https://social.techcrunch.com/2019/04/29/marriott-is-reportedly-launching-a-home-sharing-product-in-the-u-s

Dogru, T., Mody, M. and Suess, C. (2019) Adding evidence to the debate: Quantifying Airbnb’s disruptive impact on ten key hotel markets, Tourism Management, 72, 27-38.

Dogru, T., Mody, M., Suess, C., Line, N. and Bonn, M. (2020) Airbnb 2.0: Is it a sharing economy platform or a lodging corporation? Tourism Management, 78, 104049, DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104049

Dolnicar, S. (2019) A review of research into paid online peer-to-peer accommodation: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research curated collection on peer-to-peer accommodation, Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 248-264, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.02.003

Dolnicar, S. and Zare, S. (2020) COVID-19 and Airbnb – Disrupting the Disruptor, Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102961, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102961

Fleetwood, C. (2020) Airbnb commits $400m to hosts to cover COVID-19 cancellations, retrieved on May 21, 2020 from https://www.travelweekly.com.au/article/airbnb-commits-400m-to-hosts-to-cover-covid-19-cancellations

Gardiner, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Networks becoming one-stop travel shops, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 87-97, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3606

Gardiner, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) Airbnb’s offerings beyond space – before, during and after COVID-19, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

Gessner, K. (2019) Ahead of IPO, Airbnb’s consumer sales surpass most hotel brands, retrieved on May 21, 2020 from https://secondmeasure.com/datapoints/airbnb-sales-surpass-most-hotel-brands

Griswold, A. (2016) It’s time for hotels to really, truly worry about Airbnb, retrieved on July 12, 2020 from https://qz.com/729878/its-time-for-hotels-to-really-truly-worry-about-airbnb

Guttentag, D. (2017) Regulating innovation in the collaborative economy: an examination of Airbnb’s early legal issues, in D. Dredge and S. Gyimóthy (Eds.), Collaborative Economy and Tourism: Perspectives, Politics, Policies and Prospects, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 97-128.

Guttentag, D.A. and Smith, S.L. (2017) Assessing Airbnb as a disruptive innovation relative to hotels: Substitution and comparative performance expectations, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 64, 1-10.

Hajibaba, H. and Dolnicar, S. (2018a) Substitutable by peer-to-peer accommodation networks? Annals of Tourism Research, 66, 185-188, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.013

Hajibaba, H. and Dolnicar, S. (2018b) Airbnb and its competitors, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 63-76, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3604

Han, C. and Yang, M. (2020) Revealing Airbnb user concerns on different room types, Annals of Tourism Research, 103081, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103081

Heo, C.Y., Blal, I. and Choi, M. (2019) What is happening in Paris? Airbnb, hotels, and the Parisian market: A case study, Tourism Management, 70, 78-88.

Huang, D., Coghlan, A. and Jin, X. (2020) Understanding the drivers of Airbnb discontinuance, Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102798, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.102798

JustPark (2020) Sharing economy index, retrieved on July 14, 2020 from https://www.justpark.com/creative/sharing-economy-index

Kavadias, S., Ladas, K. and Loch, C. (2016) The transformative business model, Harvard Business Review, 94(10), 91-98.

MacInnes, S., Randle, M. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) Airbnb catering to guests with disabilities – before, during and after COVID-19, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

O’Neil, S. (2020) Why Priceline’s purchase of Booking.com was the most profitable travel deal of the 2000s, retrieved on October 21, 2020 from https://www.phocuswire.com/Why-Pricelines-purchase-of-Booking-com-was-the-most-profitable-travel-deal-of-the-2000s

Oliver, D. (2020) Travelers are flocking to Airbnb, Vrbo more than hotels during COVID-19 pandemic. But why? retrieved on October 21, 2020 from https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/hotels/2020/08/26/airbnb-vrbo-more-popular-than-hotels-during-covid-19-pandemic/5607312002

Petruzzi, M.A., Marques, C. and Sheppard, V. (2021) To share or to exchange: An analysis of the sharing economy characteristics of Airbnb and Fairbnb.coop, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102724.

Popper, B. (2015) Airbnb’s worst problems are confirmed by its own data, retrieved on October 1, 2020 from http://www.theverge.com/2015/12/4/9849242/airbnbdata-new-york-affordable-housing-illegal-hotels

Press, A. (2020) Airbnb moves to go public despite pandemic struggles, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/aug/19/airbnb-ipo-stock-market

Press, J. (2018) Time for Canada to take action on Airbnb, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from www.thestar.com/news/canada/2018/04/30/time-for-canada-to-take-action-on-airbnb-tax-payment-hotel-association-says.html

Prieto, M. (2020) The state of online travel agencies – 2019, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://medium.com/traveltechmedia/the-state-of-online-travel-agencies-2019-8b188e8661ac

Randle, M. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Guests with disabilities, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 244-254, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-36120

Randle, M. and Dolnicar, S. (2019) Enabling people with impairments to use Airbnb, Annals of Tourism Research, 76, 278-289, DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.04.015

Reinhold, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2018) Airbnb’s business model, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the boundaries, Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers, 27-38, DOI: 10.23912/9781911396512-3601

Reinhold, S. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) The evolution of Airbnb’s business model, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

Sainaghi, R. and Baggio, R. (2020) Substitution threat between Airbnb and hotels: Myth or reality? Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102959.

Schaal, D. (2020) Tripadvisor is trying to sell its vacation rental businesses, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://skift.com/2020/03/13/tripadvisor-is-trying-to-sell-its-vacation-rental-businesses

Seitam, D. (2020) The coronavirus – a delay to subscription fees for PLU, retrieved on November 20, 2020 from https://peoplelikeus.world/en/blog/233?action=

Slee, T. (2014) The shape of Airbnb’s business, retrieved on October 1, 2020 from http://tomslee.net/2014/05/the-shape-of-airbnbs-business.html

Staley, L. (2007) Why do governments hate bed and breakfasts? The Institute of Public Affairs Review: A Quarterly Review of Politics and Public Affairs, 59(1), 33-35.

Stevens, P. (2019) RedAwning announces integration with Trivago, retrieved on September 9, 2020 from https://shorttermrentalz.com/news/redawning-announces-integration-with-trivago

Sonnemaker, T. (2020) Here are all the companies Airbnb has acquired to help it grow into a $31 billion business, retrieved on November 16, 2020 from https://www.businessinsider.com.au/airbnb-acquisitions-tilt-crashpadder-nabewise-2020-1?r=US&IR=T

The Economist (2020) Staycationers are saving hotels and Airbnb from covid-19, retrieved on January 11, 2020 from https://www.economist.com/business/2020/08/31/staycationers-are-saving-hotels-and-airbnb-from-covid-19

Ting, D. (2017) Airbnb is becoming an even bigger threat to hotels says a new report, retrieved on August 8, 2020 from thhps://skift.com/2017/01/04/airbnb-is-becoming-an-even-bigger-threat-to-hotels-says-a-new-report

Transparent (2020) Our industry is on the front line of a global health and economic crisis, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://seetransparent.com/en/coronavirus-impact/impact-in-global-demand.html

Trejos, N. (2018) Hotel CEOs talk security, technology and room service, retrieved on August 8, 2020 from www.usatoday.com/story/travel/roadwarriorvoices/2018/02/19/hotel-ceos-talk- security-technology-and-room-service/335815002

Trenholm, R. (2015) Airbnb exec denies competition with hotels, says an Airbnb trip ‘changes you’, retrieved on August 3, 2020 from www.cnet.com/news/airbnb-exec-denies-competition-with-hotels-says-an-airbnb-trip-changes-you-somehow

von Briel, D. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) The evolution of Airbnb regulations, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

Wintermaier, P. (2020) How Booking.com became hotels’ biggest enemy, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://digital.hbs.edu/platform-digit/submission/how-booking-com-became-hotels-biggest-enemy

Witts, S. (2016) BHA boss slams dangerous Airbnb, retrieved on August 10, 2020 from https://bighospitality.co.uk/Article/2016/01/13/BHA-boss-slams-dangerous-Airbnb

Xiang, Y., Lan, L. and Dolnicar, S. (2021) Airbnb in China – before, during and after COVID-19, in S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Airbnb before, during and after COVID-19, University of Queensland.

Yudan, N. (2020) Welcome Benivo, goodbye FlatClub, retrieved on November 10, 2020 from https://www.benivo.com/blog/welcome-benivo-goodbye-flatclub

Zervas, G., Proserpio, D. and Byers, J.W. (2017) The rise of the sharing economy: Estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry, Journal of Marketing Research, 54(5), 687-705.