2 Thinking like a social scientist

Learning Objectives for this Chapter

After reading this Chapter, you should be able to:

- understand and apply the concepts of structure and agency to help you think sociologically about the world around you,

- understand and apply the concept of the sociological imagination to critically analyse different ‘real world’ examples.

The sociological imagination: agency and structure, macro and micro

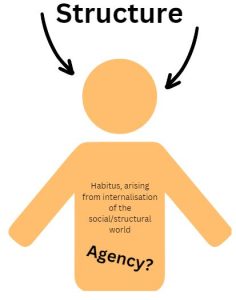

C.Wright Mills (1916-1962) coined the term ‘sociological imagination’ by which he meant the ability to connect the individual with the social, the one with the many and seek to understand broader trends, structures and ideas. Understanding this connection is helpful to think about structure and agency and our place within it. Agency is about our free will and potential to self-actualise our lives, whereas structure is about the material and immaterial conditions within which we live, for example, the systems of governance, religion, social class, social norms and rules and regulations etc. It may be helpful to think of structure and agency on a continuum, a sliding scale between the two extremes of ultimate agency and totalising structure. Neither extreme pole exists in the real world, but our society or life may shift along this kind of continuum from time to time, due to circumstance or other factors. Even though we may sometimes think of structures as limiting our agency and curtailing us, we are also the creators and maintainers of the structures around us. This interplay between agency and structure is nicely captured by the famous quote by anthropologist Margaret Mead (1901-1978): “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

The concept of the sociological imagination is also a tool to help us, as social scientists, think through agency and structure. Mills (2000 [1959]: 3) stated, “Neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both.” Indeed, Mills (2000 [1959]) drew an important distinction between private ‘troubles’ and public ‘issues’, explaining:

Troubles occur within the character of the individual and within the range of his or her immediate relations with others; they have to do with one’s self and with those limited areas of social life of which one is directly and personally aware. Accordingly, the statement and the resolution of troubles properly lie within the individual as a biographical entity and within the scope of one’s immediate milieu – the social setting that is directly open to her personal experience and to some extent her wilful activity. A trouble is a private matter: values cherished by an individual are felt by her to be threatened.

Issues have to do with matters that transcend these local environments of the individual and the range of her inner life. They have to do with the organization of many such milieu into the institutions of an historical society as a whole, with the ways in which various milieux overlap and interpenetrate to form the larger structure of social and historical life. An issue is a public matter: some value cherished by publics is felt to be threatened. Often there is a debate about what that value really is and about what it is that really threatens it. This debate is often without focus if only because it is the very nature of an issue, unlike even widespread trouble, that it cannot very well be defined in terms of the immediate and everyday environments of ordinary people. An issue, in fact, often involves a crisis in institutional arrangements, and often it involves what Marxists call ‘contradictions’ or ‘antagonisms.’

At its core, then, the sociological imagination helps us to think through two dualisms: agency/structure, and macro/micro. That is:

- agency – the ability of an individual to make free and independent choices about how they live, what they do, how they are etc, according to their own values and wishes,

- structure – the social structures that influence, constrain, and guide the ability of individuals to make free and independent choices about how they live, what they do, how they are etc.,

- micro – focusing on the smaller scale, like the individual or small groups of people, and

- macro – focusing on a larger scale, like the structure of society and social institutions situated within.

We will keep returning to the concepts of agency/structure, macro/micro throughout the book. First and foremost, however, our task here is to encourage you – as budding social scientists – to use your sociological imaginations (alongside other tools we will cover in later sections) to see the world around you through new eyes. Equipped with the sociological imagination, we social scientists can then reflect upon our own position within the world. This process of reflexivity, “involves considering one’s own place in the social world, not as an isolated and asocial individual but as a consequence of one’s experience as a member of social groups.” (Willis, 2004: 22). The sociological imagination is then not just a theoretical lens through which to perceive the world, but also an intensely practical viewpoint that allows us to see the world beyond our immediate surroundings.

The notion of reflexivity links bank to our discussion of phronetic social science in Chapter One. At its core, phronetic social science is described by Flyvbjerg (2001: 3) as focusing on the “reflexive analysis and discussion of values and interests” in ways that the natural sciences cannot. Thus, the social sciences encourage us to not deny subjectivities in research, but to instead embrace and grapple with them as meaningful and important aspects of our vocation. In doing so, we can more deeply acknowledge the impacts that the subjective values we live by have on our views about the world, including the different approaches we might take to understanding and responding to different social issues. In thinking, reflexively, through how our own values may shape and influence our views of the world, it is also helpful to consider the role of cultural and moral relativism.

Cultural and moral relativism refer to the understanding that values are dependent on and relative to the society from which they emerge. That is, your own values might be very different to someone who lives in a different country, who lived at a different time, or who lives in the same country and has had a different upbringing and different life experiences. A cultural relativist would argue that this makes neither set of values ‘right’ or ‘wrong’; they are just different. The reality of cultural and moral relativism requires that we, as social scientists, are reflexive about the ways in which we see the world as well as the values that we bring to our research and work (‘our cultural baggage so to speak’). In essence, reflexivity involves ‘bending back’ on oneself to acknowledge and understand how our own values influence how we see the world around us, as well as our place within it.

Reflection exercise

Pause for a moment and think about your own values and beliefs. Where do you think these come from, primarily? Have they changed over time? If so, what has caused them to change? What role/s do they play in shaping your day-to-day behaviours and choices?

Reflection exercise

Use your sociological imagination to think through some social issues that interest you. This may include, for example:

- climate change

- gender equity

- intergenerational poverty

- public health

- homelessness

- discrimination

- sustainable development

- food justice

- crime and justice, or many more!

Choose one or two of these (or other) social issues that you’re most passionate about and then follow the below steps:

- Take a piece of paper and draw two columns: label one ‘Agency’ and the second one ‘Structure’.

- Make a list under each column heading of the kinds of things we might like to consider when using our sociological imaginations to think through your chosen social issue/s.

- Reflect: did this approach lead you to think of anything you might not otherwise have considered in relation to your chosen social issue?

Reflection exercise

To extend your learning with regard to agency and structure, please read through the policy case study written by Staines (2021), available via the Australian New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG), entitled ‘From the ground up: developing the Cape York Girl Academy School to re-engage young women and mums from remote Australia.’ (PDF, 380KB) .’

After reading the case study, consider the below prompts for further thinking and discussion. Students might also like to share and discuss their responses with their peers, if undertaking this activity in a classroom setting.

- First, think about the challenge of lower school attendance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (from herein, ‘Indigenous’) peoples in Australia and consider the below discussion prompts.

-

- How might this challenge be explained through the lens of agency?

- How might this challenge be explained through the lens of structure?

- How might these different lenses lead to different policy responses?

- Second, think about the policy approach taken in the case study — i.e. the establishment of an Indigenous school — and consider the below discussion prompts.

-

- How does this policy response address structural issues regarding lower school attendance for Indigenous students?

- What structural matters are left unaddressed by this policy response?

- How might these other matters also be addressed?

- Third, turn your thinking towards the tensions between ground-up and top-down policymaking, including those identified in the case study. Then consider the below discussion prompts.

-

- Representing only 3% of the total Australian population means that Indigenous peoples in Australia tend to be poorly represented in state and federal politics, and often excluded from policymaking (including through a long history of generally poor consultation — e.g. see the optional reading below).

- Consider the implications of this for policymaking in Australia, including whether/how Indigenous Australians might be better empowered to lead and have meaningful input into policies that directly affect their lives.

Further optional reading to support this activity: Davis, M. 2016. Listening but not hearing: when process trumps substance. Griffith Review, 51: 73-87.

Structure and agency, through a Bourdieusian lens

The concepts of agency and structure, introduced above, are tools used by social scientists to understand how individuals act within society. As a recap, agency is the ability of individuals to interact spontaneously within society and make choices according to their own free will. Structure is the influencing factors of the social conditions that shape and constrain agency. Our choices as individuals within a society are always influenced by numerous structures. Some are imposed upon us externally, such as social class and systems of government. Others are internalised as values, for example as social and religious norms. Often, there are a mix of both external and internal elements to the structures that shape our choices. Moreover, whilst agency is inevitably shaped by structure, it is important to note that the reverse is also true. Structure is far from a natural occurrence. We, as individuals, have the ability to create and maintain the structures around us. Social scientists aim to clarify this intricate relationship between agency and structure.

One perspective on structure and agency is developed by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002). For Bourdieu, “all activity and knowledge… are always informed by a relationship between the agent’s history and how this history has been incorporated” (Schirato and Roberts, 2018: p. 133). This position influences Bourdieu’s theory of ‘habitus’:

“The habitus, as the system of dispositions… is an objective basis for regular modes of behaviours, and thus for the regularity of modes or practice, and if practice can be predicted… this is because the effect of the habitus is that agents who are equipped with it will behave in a certain way in certain circumstances” (Bourdieu 1990: 77) [Bourdieu, 1990: In other words: Essays Towards a Reflexive Sociology]

To illustrate the role of the habitus in our daily lives, consider how different people, influenced by different social factors, make their tea. A person of English heritage, according to history and social customs, might prefer to have their black tea with a dash of milk. In a similar fashion, a person of Japanese heritage may prefer to have green tea, or alternatively black tea with lemon and no milk. If a person of English heritage was to prefer black tea with lemon, this could be seen to go against customs and appear alien to “normal” English culture. Examples abound of preference within tea culture, however all highlight the effect of habitus upon our choices. The habitus can be understood to contain all the cultural preferences, or dispositions, that people bring with them when making choices. Almost always unconscious, these influencing factors allow individuals to believe they are acting according to their own agency, when in reality our decisions are always influenced by our habitus. Such a simple example is nevertheless helpful to demonstrate how the habitus can shape our decisions, no matter how small, without our awareness of it.

Although the habitus is a relatively stable set of beliefs and values created by structure, there are certain “circumstances and contexts [that] are not necessarily receptive to or in tune with it” (Schirato and Roberts, 2018: 144). For Bourdieu, the problem for social scientists is to then understand how individuals can act spontaneously in ways that are not always entirely shaped by structure itself. In other words, how does agency continue to exist despite the powerful influence of structure?

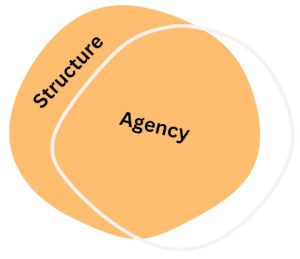

Giddens and Structuration

English sociologist Anthony Giddens (1938-present) saw the relation between agency and structure not as two opposing binaries but as a duality. Giddens’ structuration theory develops the argument that,

“people produce their social systems employing rules and resources (structures) during interaction (agency), knowingly or unknowingly reproducing these structures via routines and rituals that are often taken-for-granted or unquestioned” (Hardcastle, Usher, and Holmes 2005: 223).

Giddens proposes that agency and structure be viewed as two sides of the same coin, with each requiring the other for social practice to occur. Social institutions, as structure, are preserved by the action of individuals through some form collective agreement. This consensus takes the form of action, where for example the legitimacy of the political system is maintained by individuals collectively agreeing to attend the polling booth to vote. Without this complicit action, structure would be forced to operate differently. To continue the example above, such a government may form a military dictatorship to ensure people vote, which consequently undermines the legitimacy of structure. Giddens argues that this action of individuals in maintaining structure also means that individuals have the ability to change structure. It is through the active agency of individuals that the power of structure can be reorganised.

Individuals, groups, culture, society

The notion of the individual has developed through the history of philosophy. The individual is defined as a single human being, influenced by social structure, whilst retaining some degree of agency. In (neo)liberal capitalist societies, the individual is often understood to be a rational and self-interested being who maximises economic opportunity (‘homo economicus’). However this definition is problematic and fails to appreciate the principles of reciprocity that underlie many communitarian societies (e.g., see the example of hydrosocial territories in the Kayambi community of La Chimba, Equador, discussed by Manosalvas, Hoogesteger, and Boelens, 2021), as well as many examples of generosity and selflessness within capitalism. One example can be seen in the act of gift giving. A theory of the gift was developed by French sociologist Marcel Mauss (1872-1950), where he discussed how gift giving brings with it a certain sense of obligation that escapes the typical “individualistic” view of modern societies. Rather than a collection of isolated individuals acting out of self interest, Mauss argued that the act of gift giving develops a sense of reciprocity between individuals and groups. This reciprocity ultimately strengthens relationships between different people — a process unable to be accounted for by simply viewing individuals as self-serving and utilitarian.

Social scientists are also interested in understanding how individuals interact within social groups. Rather than simply a collection of relatively random individuals, such as in a grocery store checkout, a social group is united by some set of common interests, values or other form of membership. Belonging to a group requires adherence to certain expectations of conduct, some explicit and others implicit. A group may be small, such as a particular street gang, with certain norms and behaviours that are required to be accepted as a member. A group may also be large, such that ‘society’ broadly may be said to constitute a social group of sorts, engaged in consistent social interaction and often governed by the same legal authority. Society both shapes and is shaped by certain forces, including cultural values, institutions, and hierarchies. These forces organise individuals and smaller groups in such a way that they adhere to the expectations of a specific society. Nested within society are groups, subcultures, and individuals, who can be broadly categorised as either conforming to social expectations, or as engaging in behaviour that deviates from these norms. This distinction is a practical one, typically enforced by power structures such as government, police, and the legal system.

In the social sciences, culture refers to the (implicit and explicit) shared beliefs, values, customs, rules, behaviours, and artefacts that characterise a group or society. It encompasses all aspects of social behaviour and norms and provides a framework for understanding the behaviour of individuals within that society. Culture can be defined as the “non-biological aspects of society, all those things which are learnt or symbolic, including convention, custom and language” (Willis, 2004: 73). It is culture that distinguishes the social organisation of humans from that of other animals.

Othering: Processes of making self and other

As you will have seen in this Chapter, an integral part of social science research is understanding relationships, especially between the self and ‘Other’. We are individuals but also part of society; relationships are how we fit into a given society. In the social sciences we use a range of methods to study the self (e.g., especially in psychology) and others (e.g., especially in anthropology). In fact, understanding more about ourselves by studying others also has a long tradition: the search for common traits or cultural and social differences has been at the forefront of sociology and anthropology, for example. In these (and other) disciplines, the Other and their characteristics of otherness are often studied not only to better understand relationships between ‘us’ and ‘Other’, but also to pose problems. This is because the process of labelling someone as ‘Other’ inherently places them at the margins, setting them apart from mainstream society on the basis of particular traits, and decentring their own identity. Moreover, othering often takes place on the basis of particular traits, such as a person’s religious, social, cultural, sexual, or ethnic identities, and thus can have significant negative effects — giving way to ostracisation and discrimination. This process feeds into an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality that creates ‘in’ and ‘out’ groups as a result.

Reflection exercise

Sex, gender, and sexuality

Example aspects of social identity that can give way to ‘othering’ are sex, gender, and sexuality: concepts that play a significant role in shaping our identities and experiences. While sex refers to a biological classification based on anatomy, hormones, and chromosomes, gender refers to the social and cultural norms, expectations, and behaviors that are associated with being labeled a particular sex. Gender is not solely based on biological sex and can vary across cultures and time periods.

Male and female are the most common binary sexes, but there are also individuals who have intersex conditions and may have bodies that do not fit within typical binary definitions of male or female. The term ‘nonbinary’ is regularly used as a sort of ‘catch all’ to include diverse individuals who do not identify as either male or female.

Understanding non-binary: excerpts from a correspondence

To learn more about what it means to identify as non-binary, you might like to watch the following TedX Talk, ‘Understanding non-binary: excerpts from a correspondence’ (YouTube, 15:43).

Typically, ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’ are gendered traits that are used to describe certain qualities and behaviours that are expected to be associated with being male or female. Masculinity is often associated with toughness, assertiveness, and competitiveness, while femininity is often associated with softness, emotional expressiveness, and nurturing. In reality, however, traits that are considered either ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ exist on a spectrum; individuals can exhibit both masculine and feminine traits, regardless of their biological sex or gender identity. Indeed, critical scholars have also drawn attention to the ways in which these gendered traits are bound up in expressions of power and domination. That is, the categories themselves are oppressive social constructs rather than objective reflections of reality. Feminist scholar and famous existentialist, Simone de Beauvoir, provides an example of how the notion of femininity can be used to oppress and deny rights and freedoms to those who identify as women.

The myth of femininity

Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) was chiefly influential in second-wave feminism. In her book ‘The Second Sex’ (1949), she argued that femininity was a myth that served to oppress women and deny their rights to free and equal participation in society.

You might recall the below video from earlier in the semester. To learn more, re-watch it and think about the kinds of implications this thinking has had on the social institution of the family, and on conceptions of gender today.

In addition to sex and gender, sexuality refers to an individual’s sexual orientation and desires. For instance, sexual orientation can include — amongst other orientations — heterosexuality, homosexuality, bisexuality, and pansexuality. Often used, for instance, the LGBTQI+ acronym stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, and intersex, with the plus sign representing a variety of other identities, including asexual, aromantic, and more. Sexuality is, indeed, a complex and multi-faceted aspect of our identities that can be shaped by a variety of influences, including biological, social, cultural, and psychological factors.

Our sex, gender, and sexuality are important aspects of our social identities that can have significant influences on our lives. Indeed, they can be sources of opportunity as well as oppression, depending on the social and cultural milieu within which a person exists. Moreover, an intersectional perspective on these concepts recognises that individuals can face multiple forms of oppression and privilege based on their sex, gender, masculinity, femininity, sexuality, but also other aspects of their identity. For example, a transgender woman of colour may face discrimination and prejudice based on both her gender identity and her race. Additionally, individuals may also experience privilege based on one aspect of their identity while facing oppression based on another aspect. For instance, a white, gay man may face discrimination based on his sexual orientation, but also benefit from privilege based on his race. Intersectionality also highlights the importance of recognizing the unique experiences and perspectives of individuals who belong to multiple marginalized communities. For example, a black, lesbian woman may face discrimination and prejudice based on her race, sexuality, and gender identity, and may also experience unique forms of discrimination and violence that are specific to her intersecting identities.

Read more on sex, gender, and sexuality

To read more about sex, gender, and sexuality, particularly from a sociological perspective, the following freely available resource may be useful:

Little, W. and McGivern, R. 2022. ‘Gender, sex, and sexuality.’ In. Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition.

Globalisation, borders, capitalism

The social sciences are also interested in explaining how different cultures and societies interact with each other on a global as well as local scale. From the ancient empires that rose and fell, to colonisation during the expansion of the British and Spanish empires, to the new forms imperialism led by American expansionism, human history has long been a global history. This history, far from a unified tale of the equality of human beings sharing a single world, is divided: along lines of class, race, religion, nationality, and gender. It is the job of social scientists to address these conflicts and inconsistencies, so as to imagine a better world united by a shared humanity.

Borders mark the formal boundaries between different nation-states. Borders between groups of people are nothing new, but the formalised demarcation between political units or nation-states as marked in maps and determined to be legally binding is a relatively new development. Early borders were physical, such as rivers, mountains and the sea. People were often divided into lowland and highland peoples, or land and sea peoples, who traded and were in contact, even though they were physically distanced. James Scott has argued that in Southeast Asia peoples rejected formalised states and such political manifestations by distancing themselves from lowland centres of commerce and state building by moving into the highlands and maintaining more egalitarian and anarchic societies. With the rise of the nation-state in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries, borders became more politically significant. Nation-states sought to define their territories and assert their sovereignty over their borders. To do this, they employed techniques such as boundary markers, boundary surveys, and maps. These techniques were used to physically demarcate the border and provide a clear visual representation of the territory controlled by a given state. Thus, bordering techniques include the physical building of border fences, walls and other barriers as well as the technological in the form of passports and other identification documents that tie us via citizenship to a particular nation-state.

Borders and bordering techniques have a long history tied to war, imperialism, and economic exploitation. Legal boundaries are often disputed by different ethnic, religious or otherwise distinctive groups. Conflicts over borders as the result of colonisation are often the result of arbitrary border lines drawn on a map, then sanctified as law by colonising entities. Due to the haphazard divisions of geographic areas without consideration for the people who lived there, such as across Africa in the late 1800s, and across Australia from the late 1700s, the peoples that occupy a particular area often became forcibly unified under a nation-state, despite significant cultural differences. In other cases ethnic groups were split up by such arbitrary borders across multiple nation-states (see the reflection exercise, below).

Reflection exercises on borders

Read the following blog post from the library of Congress and analyse the maps on the website that chart the changing US-Mexico border:

- Osborne, C. 2015. ‘The changing Mexico-US border‘. Library of Congress Blog, December 18.

Then read the following article in The Conversation:

- Leza, C. 2019. ‘For Native Americans, US-Mexico Border is an “imaginary line”.’ The Conversation, March 19.

After reading these articles:

- Think about the effects and affect of shifting borders and what borders mean to people who are living on either side of them. Write a short list of peoples who have been affected by the US-Mexico border and how they have been affected. What commonalities or differences exist between different groups and on what basis?

- Think about where you live, what issues arise at the border and how are they dealt with? Who deals with these issues? Reflect on the power dynamics at play – who has power and who is subject to bordering and/or othering (see above) practices.

The nation-state is also closely linked to the emergence of capitalism and both developed in step. The nation-state provided the market security, infrastructure and more cohesive regulations across a larger geographic area. To sustain economic growth, nation-states entered into competition with other states, that also have the potential for conflict. However the general fruitful collaboration between the political (nation-state) and economic (capitalism) system has generated the world we inhabit today. This has made capitalism the dominant ideology across the globe. Fundamentally an economic system, capitalism has nevertheless evolved over its relatively short history into a political and social system. This system shapes the lives of individuals, as well as defined the borders of nations and interactions between them. Ellen Meiksins Wood (1999: p.2) defines capitalism as “a system in which goods and services, down to the most basic necessities of life, are produced for profitable exchange, where even human labour-power is a commodity for sale in the market, and where all economic actors are dependent on the market”. Whilst workers require the market for sale of their labour, capitalists also require it for the purchase of labour and the sale of goods and services.

As an ideology, capitalism is treated as a natural, necessary system resulting from Enlightenment notions of human nature as rational, self-interested, and competitive. However, using a social science lens allows us to see capitalism as a relatively new idea that has developed out of conflict, exploitation, and imperialism. Capitalism today is inseparable from globalisation, defined by international trade systems, markets, and the supremacy of multi-national corporations.

Globalisation refers to the increasing interconnectedness and interdependence of the world’s economies, societies, and cultures due to advancements in communication, transportation, and technology. Whilst it was a celebrated concept and reality in the 1990s and early 2000s, when euphoria of this interconnectedness and global connection was meant to diminish conflict in a new liberal world order of peace and prosperity, such analysis was short lived. Critics soon showed that globalisation rests on exploitation and unequal global power relations. For example, Eric Wolf’s work, “Europe and the People Without History” shows how globalisation has been driven by the interests of dominant states and capital, leading to cultural and economic imperialism. He argues that globalisation is not a neutral process, but one that reinforces the power dynamics between the Global North and South. His work also demonstrates that globalisation is not a new phenomenon but the latest word to describe a long process of economic exchange and integration across the world. Indeed, Sidney Mintz, in his work “Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History”, critiques the way colonial sugar producing islands in the Caribbean were thrust into unequal trading relations with the colonial homeland consuming the sugar. He shows how these unequal power dynamics lead to the exploitation of resources and people in the Global South. Mintz also documents the ways in which the global trade of sugar has shaped cultural and economic systems, creating a dependence on sweet foods in the Global North. Both studies offer important perspectives on the cultural and economic impacts of globalisation, emphasising the need to critically examine the process and its effects on people and societies.

In the 1970s and 1980s Immanuel Wallerstein developed world systems theory as a theoretical framework to explain the dynamics of the global capitalist economy and its effects. The theory was developed as an alternative to traditional views of economic development that emphasised the role of individual nation-states. According to world systems theory, the global economy can be divided into three main categories: core, semi-periphery, and periphery. Core countries are highly industrialised and economically dominant, possessing a disproportionate amount of wealth and power in the world system. Peripheral countries, on the other hand, are less industrialised and economically dependent, often serving as suppliers of raw materials for the core. Semi-peripheral countries occupy a middle ground between the two, sometimes acting as intermediaries between the core and periphery. The relationships between these three groups are characterised by unequal power dynamics and exploitation. Core countries are seen as benefiting from the exploitation of peripheral countries, which are subjected to low wages, poor working conditions, and limited access to (often their own) resources. Over time, this leads to unequal development, poverty, and underdevelopment in peripheral countries, perpetuating their position as suppliers of cheap labor and raw materials.

Resources to support further learning

Readings:

- Mills, C.W. 2000 [1959]. ‘The promise’. In. Mills, C. The sociological imagination (2nd edition), chapter 1. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Staines, Z. 2021. From the ground up: developing the Cape York Girl Academy school to re-engage young women and mums from remote Australia. Australia and New Zealand School of Government, John. L. Alford Case Study Library: Canberra.

- National University. n.d. ‘What is the sociological imagination?‘ Blog post.

Other resources:

- Dhingra, P. 2019. ‘Why should you use your (sociological) imagination’ (YouTube, 15:53).

- Phoenix, A. and Holloway, W. (2011). The Agency-Structure Dualism – Critical Social Psychology (YouTube, 2:34). [A transcript of the video (PDF, 24KB)]