1 What are the social sciences?

Some of the earliest written and spoken accounts of human action, values, and the structure of society can be found in Ancient Greek, Islamic, Chinese and indigenous cultures. For example, Ibn Khaldoun, a 14th-century North African philosopher, is considered a pioneer in the field of social sciences. He wrote the book Muqaddimah, which is regarded as the first comprehensive work in the social sciences. It charts an attempt to create a universal history based on studying and explaining the economic, social, and political factors that shape society and discussed the cyclical rise and fall of civilisations. Moreover, indigenous peoples across the world have contributed in various and significant ways to the development of scientific knowledge and practices (e.g., see this recent article by Indigenous scholar, Jesse Popp – How Indigenous knowledge advances modern science and technology). Indeed, contemporary social science has much to learn from indigenous knowledges and methodologies (e.g., Quinn 2022), as well as much reconciling to do in terms of its treatment of indigenous peoples the world over (see Coburn, Moreton-Robinson, Sefa Dei, and Stewart-Harawira, 2013).

Nevertheless, the dominant Western European narrative of the achievements of the enlightenment still tends to overlook and discredit much of this knowledge. Additionally, male thinkers have tended to dominate within the Western social sciences, while women have historically been excluded from academic institutions and their perspectives largely omitted from social science history and texts. Therefore, much of the history of the social sciences represent a predominantly white, masculine viewpoint. That is not to say that the concepts and theories developed by these male social scientists should be outright discredited. Nevertheless, in engaging with them we must understand this context; they are not the only voices, nor necessarily the most important. Indeed, it is crucial therefore that the history of the social sciences is continually re-examined through a critical lens, to identify gaps within social scientific knowledge bases and allow space for critical revisions that broaden existing concepts and theories beyond an exclusively masculine, Western-centric perspective. We seek to adopt such an approach throughout this book. However, to critique and question Western social scientific perspectives, we must first understand them.

Social sciences in the Western world

The study of the social sciences, as developed in the Western world, can be said to emerge from the Age of Enlightenment in the late 17th Century. Beginning with René Descartes (1596-1650), both the natural and social sciences developed from the concept of the rational, thinking individual. These early Enlightenment thinkers argued that human beings use reason to understand the world, rather than only referring to religion. Other thinkers around this time such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), M. de Voltaire (1694-1778) and Denis Diderot (1713-1784), began to develop different methodologies to scientifically explain processes in the body, the structure of society, and the limits of human knowledge. It was during this period that the social sciences grew out of moral philosophy, which asks ‘how people ought to live’, and political philosophy, which asks ‘what form societies ought to take’. Rather than only focusing on descriptive scientific questions about ‘how things are’, the social sciences also sought answers to normative questions about ‘how things could be’. This is one of the central differences between the natural sciences and the social sciences. This era of Enlightenment marked an important turning point in history that gave way to further developments in both the natural and social sciences.

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) is often regarded as one of the most influential philosophers for the development of the social sciences. In his work, Kant develops an epistemology that accounts for the objective validity of knowledge, due to the capacities of the human mind. In other words, how can we as individual people come to know facts about the world that are true for all of us. Social scientists, such as Émile Durkheim (1858-1917) and Max Weber (1864-1920) critically developed the work of Kant to explain social relations between individuals.

Émile Durkheim prioritised the validity of social facts over the values themselves, continuing the tradition of ‘positivism‘ (an ontological position that we discuss later in this Chapter). Durkheim argued that there is a distinction between social facts and individual facts. Rather than viewing the structure of the human mind as the basis for knowledge like Kant, Durkheim argued that it is society itself that forms the basis for the social experience of individuals. Social facts should therefore, “be treated as natural objects and can be classified, compared and explained according to the logic of any natural science” (Rose, 1981: 19). Durkheim developed his methodology using analogies to the natural sciences. For example, he borrowed concepts from biology to understand society as a living organism.

TRIGGER WARNING

The following section contains content which may be triggering for certain people. It focuses on the sociology of suicide, including discussion of self-harm and different forms of suicide as it exists within society.

Durkheim and Suicide

Emile Durkheim’s 1879 text ‘Suicide: a Study in Sociology’ is a foundational work for the study of social facts. Durkheim explores the phenomenon of suicide across different time periods, nationalities, religions, genders, and economic groups. Durkheim argues that the problem of suicide can not be explained through purely biological, psychological or environmental means. Suicide must, he concludes, “necessarily depend upon social causes and be in itself a collective phenomenon” (Durkheim 1897: 97). It was and continues to be a work of great impact that demonstrates that, what most would consider an individual act is actually enmeshed in social factors.

In his text, Durkheim identifies some of the different forms suicide can take within society, four of which we discuss below.

Egoistic Suicide

Egoistic suicide is caused by what Durkheim terms “excessive individuation” (Durkheim 1897: 175). A lack of integration within a particular community or society at large leads human beings to feel isolated and disconnected from others. Durkheim argues that “suicide increases with knowledge”(Durkheim 1897: 123). This is not to say that a particular human being kills themselves because of their knowledge; rather it is because of the decline of organised religion that human beings desire knowledge outside of religion. It is thus, for Durkheim the weakening organisation of religion that detaches people from their (religious) community, increasing social isolation. According to Durkheim, the capacity of religion to prevent suicide does not result from a stricter prohibition of self-harm. Religion has the power to prevent someone from committing suicide because it is a community, or a ‘society’ in Durkheim’s words. The collective values of religion increases social integration and is just one example of the importance of community in decreasing rates of suicide. Isolation of individuals, for Durkheim, is a fundamental cause of suicide: “The bond attaching man [sic] to life relaxes because that attaching him [sic] to society is itself slack” (Durkheim 1897: 173).

Altruistic Suicide

Durkheim notes another kind of suicide that stems from “insufficient individuation” (Durkheim 1897: 173). This occurs in social situations where an individual identifies so strongly with their beliefs of a group that they are willing to sacrifice themselves for what they perceive to be the greater good. Examples of altruistic suicide include suicidal sacrifice in certain cultures to honour their particular God, soldiers who go to war and die in honour of their country, or the ancient tradition of Hara-kiri in Japan. As such, Durkheim notes that some people have even refused to consider altruistic suicide a form of self-destruction, because it resembles “some categories of action which we are used to honouring with our respect and even admiration”(Durkheim 1897: 199).

Anomic Suicide

The third kind of suicide Durkheim identifies is termed anomic suicide. This type is the result of the activity of human beings “lacking regulation”, and “the consequent sufferings” that are felt from this situation (Durkheim 1897: 219). Durkheim notes the similarities between egoistic and anomic suicide, however he notes an important distinction: “In egoistic suicide it is deficient in truly collective activity, thus depriving the latter of object and meaning. In anomic suicide, society’s influence is lacking in the basically individual passions, thus leaving them without a check-rein” (Durkheim 1897: 219).

Fatalistic Suicide

There is a fourth type of suicide for Durkheim, one that has more historical meaning than current relevance. Fatalistic suicide is opposed to anomic, and is the result of “excessive regulation, that of persons with futures pitilessly blocked and passions violently choked by oppressive discipline” (Durkheim 1897: 239). These regulations occur during moments of crises, including economic and social upheaval, that destabilise the individual’s sense of meaning. It is the impact of external factors onto the individual, where meaning is thrown to the wind for the individual, that characterises fatalistic suicide.

Durkheim’s sociological study of suicide was a groundbreaking work for social sciences. His methodology, multivariate analysis, provided a way to understand numerous interrelated factors and how they relate to a particular social fact. His findings, particularly the higher suicide rates of Protestants, compared to Jewish and Catholic people, was correlated to the higher rates to individualised consciousness and the lower social control. This study, despite criticisms of the generalisations drawn from the results, has had a remarkable impact on sociology and remains a seminal text for those interested in the social sciences.

Max Weber was also influenced by the work of Kant. Unlike Durkheim, Weber “transformed the paradigm of validity and values into a sociology by giving values priority over validity” (Rose, 1981: 19). Culture is thus understood as a value that structures our understanding of the world. According to Weber, values cannot be spoken about in terms of their truth content. The separation between values and validity means that values can only be discussed in terms of faith rather than scientific reason. For Weber, only when a culture’s underpinning values are defined can facts about the social world be understood.

The philosophy of G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831) also greatly shaped the development of the social sciences. As argued by Herbert Marcuse (1941: 251-257), Hegel instigated the shift from abstract philosophy to theories of society. According to Hegel, human beings are not restricted to the pre-existing social order and can understand and change the social world. Our natural ability to reason allows human beings to create theories about our world that are universal and true.

Karl Marx (1818-1883), often regarded as the founder of conflict theory, was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Hegel. For example, Hegel emphasises that labour and alienation are essential characteristics of human experience, and Marx applies this idea more concretely to a material analysis of society, dividing human history along the lines of the forces of production. In other words, Marx understood that labour was divided in capitalist society according to two classes that developed society through a perpetual state of conflict: the working class, or ‘proletariat’, and the class of ownership, or ‘bourgeoisie’ (we talk more about Marx’s conflict theory in Chapter 3).

Overall, the social sciences have a long and complex history, influenced by many different philosophical perspectives. As alluded to earlier, however, any account of the historical beginnings of the social sciences must be understood to be embedded within dominant systems of power, including for example colonisation, patriarchy, and capitalism. Indeed, any history of the social sciences is already situated within a narrative, or ‘discourse’. Maintaining a critical lens will allow for a deeper understanding of the genesis of the social sciences, as well as the important ability to question social scientific approaches, understandings, findings, and methods. It is this disposition that we seek to cultivate throughout this book. After all, as Marx famously wrote, “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.”

Defining Key Terms

Descriptive: A descriptive claim or question seeks to explain how things work, what causes them to work that way, and how things relate to one another.

Normative: A normative claim or question seeks to explain how things ought to work, why they should work a certain way, and what should change for things to work differently.

Labour: For Marx, labour is the natural capacity of human beings to work and create things. Under capitalism, labour primarily produces profits for the ruling class. (Please note, we return to the notion of labour in later chapters, and explore other understandings and definitions of this term.)

Alienation: Workers, separated from the products of their labour and replaceable in the production process, become separated or ‘alienated’ from their creative human essence. (Please also see Chapter 3 for a further explanation of the concept of alienation under Marxism.)

Resources to support further learning

Relevant readings:

- Gorton, W. ‘The Philosophy of Social Science.’

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2001. ‘The science wars: a way out.’ In. Flyvbjerg, B. Making social science matter, chapter 1. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

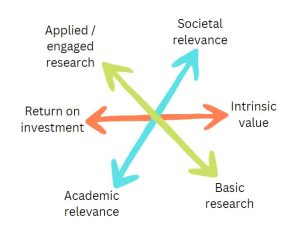

- Carré, D. 2019. ‘Social sciences, what for? On the manifold directions for social research.’ In. Valsiner, J. (Ed.) Social philosophy of science for the social sciences, pp. 13-29. Springer: Cham.

- Schram, S. 2012. ‘Phronetic social science: an idea whose time has come.’ In Flyvbjerg, B., Landman, T. and Schram, S. (Eds.) Real social science: applied phronesis. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Bunge, M. (2003). Emergence and Convergence: Qualitative Novelty and the Unity of Knowledge. University of Toronto Press.

Other resources:

- Video: Soomo, ‘An animated introduction to social science’ (YouTube, 4:35).

- Video: ‘Introduction to the social sciences’ (YouTube, 8:34).

- Podcast: Theory and Philosophy Podcast, ‘Bent Flyvbjerg – Making Social Science Matter’ (YouTube, 44:06). (Note, discussion of phronesis starts at 7:51)

- Video: ‘Importance of social science with Professor Cary Cooper’ (YouTube, 4:13).