III.3. Communication about CSR

Franzisca Weder and Marte Eriksen

The lady…

As I sat there with my almond-milk-cappuccino, I suddenly got angry with the lady. Hey Birkenstock-Lady, you left without telling me what’s next? So, corporations are doing great. And they communicate about it. That’s awesome. So I can buy the Coke bottle made of 70% recycled plastic and then I’m not quite responsible for climate change, am I? My carbon footprint is anyway not comparable to the emissions of Coca Cola as a big corporation, hm? Or think about Nestlé – they are doing pretty great after being blamed with stealing water in Africa and forcing people to buy the water they sell in plastic bottles – bastards!

But is this my opinion? How much is this opinion framed by what I read about the “big polluters” and nasty corporations destroying our ecological habitats. And it also feels like that the more big corporations communicate about “saving the world”, “doing good” and “a better future”, the more they are under public observation; the more they communicate their CSR efforts, the more attention people spend on their behaviour and also the more likely they blame them for their misconduct.

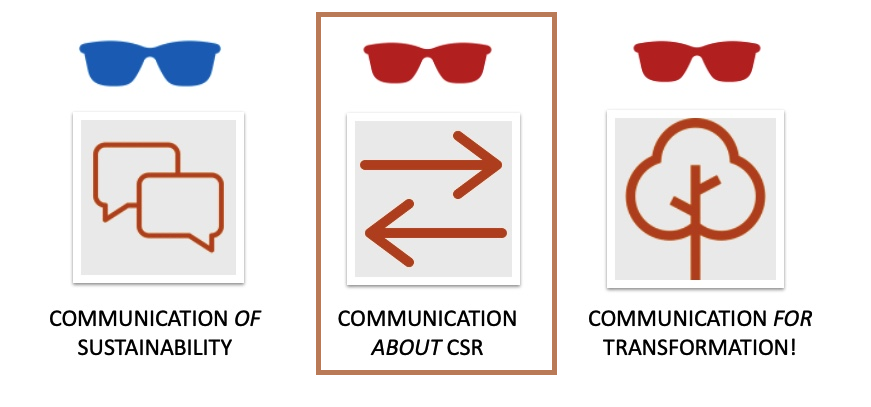

Where is opinion created? What role are public discourses and the media playing in CSR communication – how important are the issues that are represented in the media for organizations? These are questions that open up a new dimension of CSR communication: communication about CSR. This dimension also includes negotiation processes about if corporations have responsibility and for what, about the instances that secure that those corporates take the allocated responsibility. And it includes the side effects of CSR communication and how (much) especially negative media reporting affects corporations, their reputation and thus their processes and organizational sustainability.

Communication about CSR and sustainability is based on an understanding of communication as process of sense- and meaning making. Therefore, communication about CSR grounds in a social constructivist paradigm, and, as the following overview shows, it is different to the rather one-directional information based communication processes like CSR reporting which we explored in the previous chapter.

Image: “Dimensions of Sustainability Communication” by Franzisca Weder

Communication about CSR (and sustainability) is further conceptualized as deliberative, again including negotiation processes about the meaning of responsibility and sustainability as normative principle that guides the allocation and taking of responsibility, about the issues that are relevant within a sustainable development framework and the problems that need to be tackled in a multiple crisis scenario, and thus about solutions that are necessary; to summarize:

Communication about CSR / Sustainability

Direction / mode of communication:

Deliberative, horizontal, many to many

Function:

Deliberation, production of intersubjective/shared concepts, frames

The direction of communication about CSR is rather divers; various communication processes produce an understanding of the world and intersubjective and thus shared concepts of individual and organizational behavior within certain social and cultural contexts and situations – and within this world. Communication about responsibility and sustainability is more culture oriented or – vice versa – influenced by those social and cultural contexts. Communication about responsibility and sustainability gives sense and produces knowledge and visions.

Where is communication about sustainability happening?

Who is taking part in these sense making, in public negotiation and deliberation processes? Who talks about responsibility and sustainability in the public and who drives the public discourse?

The so called public sphere has been defined by various media and communication scholars, based on philosophical, sociological and political thinking and theories. One model of the public sphere with a communication focus is a rather structure and system oriented concept of the public sphere embracing all societal subsystems and the media playing a key role in observing the systems and provide a reflection on what the systems are doing (mirror-model, further information). Another concept of the public sphere also has strong focus on communication processes; it grounds in the differentiation of public and private and calls all events and occasions ‘public’ when they are open to all, in contrast to closed or exclusive affairs (Habermas, 1989). Based on this understanding, the Public Sphere is a ‘realm of our social life’ where public opinion can be formed; for a deliberative democracy access needs to be guaranteed to all citizens. A public sphere for us is a discursive and conversational space in which individuals and groups or networks of individuals can discuss matters of mutual interest. It is also possible to get to an agreement or common sense or even common decision and judgement.

Jürgen Habermas, who is for sure the most prominent sociologist who conceptualized the public sphere, defines the public sphere further as obligatory for a “society engaged in critical public debate” (Habermas); the conditions are that all citizens have access and that in the public sphere a critical discourse, and thus the formation of public opinion can happen (this has been further developed by i.e. Mouffe / Laclau, 2015) . The media reproduce the public sphere, they integrate organizations and societal subsystems in the society (socialization) and individuals in the society, in the societal subsystems (as citizens in politics etc.) and in organizational contexts. Read more about the genesis of the idea and concept of the ‘public sphere’ in the area of enlightenment and the development of related concepts).

If the focus in on communication as deliberation process related to certain topics, issues and opinions, the we can speak of a public discourse. A discourse is defined as communication between people – mostly within a certain structure. a discourse is a debate or ‘serious discussion’ of a particular topic, event, issue or subject. It constructs the individual experience and understanding of the world (sense making!).

There is a stream at the intersections of sociology, politics and language that explores public discourses with a specific focus on power dynamics and control of discourses and of how the world is perceived (read more), social theory often studies discourse with a focus on power (see Foucault-Habermas debate). Disciplines working with the concept of discourse are as said sociology, anthropology, philosophy, and the so called discourse analysis (see Fairclough, 2001). Without digging deeper in the power dynamics and antagonistic character of the public discourse on social responsibility, one of our key questions in this book is again: Who is communicating about CSR and sustainability, and who are the dominant voices, opinions? And later: what (key) role do the media play in a public CSR discourse?

Who is participating in public discourses – and what role do the media play?

Again, one of the key actors in the CSR discourse are civil society organizations who foster discourses on social change and transformation processes, the implications of the climate crisis and a sustainable future in alternative media, within assemblies, or through social networks.

Education institutions play an important role in terms of engagement with different interpretations of the future and sustainable development. The World Economic Forum points to the key role of education ministries, institutions and training facilities in public negotiation processes of agreements to reinforce efforts taken towards sustainable development and the realization of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals:

“…Article 6 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) stipulates that education, training, and public awareness on climate change must be pursued. …with negotiations on these global agreements far from complete, it is vital that policymakers’ emphasis on education continues to be reinforced…. A strong education system broadens access to opportunities, improves health, and bolsters the resilience of communities – all while fueling economic growth in a way that can reinforce and accelerate these processes. Moreover, education provides the skills people need to thrive in the new sustainable economy, working in areas such as renewable energy, smart agriculture, forest rehabilitation, the design of resource-efficient cities, and sound management of healthy ecosystems. …education can bring about a fundamental shift in how we think, act, and discharge our responsibilities toward one another and the planet. After all, while financial incentives, targeted policies, and technological innovation are needed to catalyze new ways of producing and consuming, they cannot reshape people’s value systems so that they willingly uphold and advance the principles of sustainable development. Schools, however, can nurture a new generation of environmentally savvy citizens to support the transition to a prosperous and sustainable future” (World Economic Forum, 2015).

Here, not only education ministries and policy makers, but also schools, universities and scientific institutions, play a key role in education for sustainability (see next chapter), but also in keeping the discourse going. This has political implications, because a public discourse is seen as closely linked to policy making. But scientific institutions in particular drive the scientific discourse and thus the process of introduction of a new concept. They develop theories and approaches to better understand sustainability and sustainable development, and offer methodologies to study social change and transformation processes. Thus, scientific institutions contribute to the discourse about sustainability and responsibilities of organizations, and with that, they support the ‘normalization’ and institutionalization of sustainability as guiding principle of action on an individual, organizational and societal level.

As mentioned, political institutions are probably the most influential communicators in the public sustainability discourse. They can raise public awareness and initialize communication on all levels, individual, organizational and societal. Political assemblies, round tables and working groups are the space where the SDGs have been negotiated on a supranational level; furthermore, on a transnational level strategies have been developed like the “Green Deal” in Europe or frameworks like the “taxonomy“, mentioned in part I.

Even on a local and community level, citizen forums or public hearings are conversational spaces where sense making around national climate policies or business responsibilities are discussed and decisions negotiated. One example:

“The French city of Antony set up a €600,000 participatory budgeting project to involve residents directly in setting priorities for local sustainable development. Based on the full list of SDGs, the administration defined 20 local issues, including more green spaces, promoting sustainable mobility, and bolstering a circular economy.” (Citizen Lab, 2022).

All residents above the age of 16 were able to share proposals and projects to reach one of the predefined goals. These proposals were discussed by a dedicated selection committee and put to a community vote. 20 winning projects were selected, including planting a microforest, setting up a collective garden and chicken coop, and creating an inventory of local biodiversity. These actions tie into SDG 13 (Climate Action), among others.

In the opposite to their dominance when it comes to communication of CSR and sustainability, corporations and business, have been involved in conferences, political discussions and roundtables or workshops around the SDGs or national sustainability strategies – but this not always something they talk about. Today, big corporations do play a major role in global climate change consortiums and meetings, like the ‘Conference of the Parties’ (COP).

Image: “UN Climate Change Conference UK 2021” by UK Government, is licensed under United Kingdom Open Government Licence v3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Matthew TenBruggencate on Unsplash

Business have a significant stake in the conversation at this multinational conference. Company representatives play a key role in shaping the political agendas – which is wanted, because the conference of the parties (COP) states that climate change is too large for governments alone to deal with and businesses need ‘long-term certainty for investment’ (so the British premier Cameron at COP21.) However, while in political negotiation processes corporations are influential (‘lobbying’), this role in shaping change processes and thus the future is only rarely debated in the media.

So it is to state, that media corporations do not play a major role themselves when it comes to political decision making, however, they are crucial in societal transformation processes. As introduced at the beginning of the book, in today’s “risk society” (Beck, 1992), the climate crisis is not only about global changes and ecological decline but also about the communicative capacity of the society to respond (Hackett et al., 2017, p. 2). Here, media (the main means of mass communication: broadcasting, publishing, and the internet) do play critical role!

Therefore, in this section of the book, we want to further explore media representations of crisis narratives, responsibility and sustainability, and how much they not only create and maintain a public discourse on the climate crisis but much more are an important critique and control instance in the society pointing to misbehavior in CSR communication and in transparency in terms of communication about sustainability and related lobbying and policy making behind the curtains.

Communication about CSR and the media

Let’s have a look into the media and check some headlines:

“Antarctica loses three trillion tons of ice”, “Red-hot planet: All-time records have been set all over the world during the past week” – those headlines show how environmental issues, especially issues related to climate change, are communicated in the mass media: with sensational headlines, partly scary, at least full of conflict.

“Going Zero Waste”, “Simple solutions for natural living” – those are titles of sustainability blogs, influencer pages and their social media communication, creating and crafting a different, more positive narrative of the future.

“Sustainability is the new growth”, “Less CO2 emissions”, “indulgence is our nature” – from a PR and marketing perspective, environmental awareness and sustainability as core value is communicated increasingly by corporates and finds it’s representation in social as well as traditional media.

The mass-media are ‘key actors’ in the identification and interpretation of environmental issues’ (Boykoff & Boykoff 2007, 1192) and the general public often relies on the media to help them make sense of large amounts of information, especially when it comes to environmental and climate change related issues. In fact, Hansen (2011) argues that much of what we know about ‘the environment’ and our relationship to nature comes from media coverage, not only our beliefs and knowledge, but also how we ‘view, perceive, value and relate’ to the environment.

Without the media, it is unlikely that important problems, environmental or otherwise, would enter the realm of public discourse or become political issues.

What we know (or believe we know) about the world and the environment is largely based upon the information provided by the media sources we are exposed to. ‘The environment’ emerged as an issue of public concern in the 1960s (Hansen 1991) and while public interest in environmental issues has ebbed and flowed, recent research suggests that it has been increasing since the 1980s, particularly with the advent of climate change as a global issue (Johnston & Gulliver, 2022).

Today, stories about Climate Change, natural hazards and health risks fit perfectly to the media’s logic of “only bad news is good news”. Alongside reporting on melting glaciers, degrading ecosystems, water scarcity and droughts, almost all green advertisements include strategically communicated images of windmills, solar panels and heavily loaded orange trees, which frames and influences our perception of the environment.

This often controversial or at least critical content is produced and communicated by various professions: journalists who report about the warming climate and increasing rates of extinction of animals and plants across all media (TV, newspapers, magazines, films, social media); however, there is a new story sneaking in the public discourse – a story about balance, harmony and restoration. The sustainability story.

The lady …

In a new media environment, sustainability bloggers who promote environmental friendly fashion and sustainable travel modalities, and PR people and marketers who follow a green marketing approach, who conceptualize CSR management, publish their annual sustainability report, realize corporate greening campaigns, sometimes misleading (Cox, 2013, p. 289) or even “greenwashing” corporate behaviour (Weder et al., 2018; Elving et al., 2015; see more below), but definitely trying to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (UN, 2021). And politicians who also implement environmental issues in their policy and – vice versa – “hop on” issues that seem to be relevant for the corporate world, are irritated by NGOs and activists, stimulating engagement and resistance in relation to global developments, corporate behavior and/or national and regional politics.

Von Zabern and Tulloch (2020) argue that mass media not only reflect, but also actively “contribute to the creation of public discourse and understanding” (p. 26) and cannot be separated from economic and political systems and instead are prone to culturally reproduce these broader economic and political power relationships, echoed by Lester who contended in 2010 that news is constructed through the lens of society and culture.

To summarize, the media have the ability to shape public perceptions and attitudes about scientific issues and therefore have a crucial responsibility themselves (!) to present scientific information and opinions to audiences (Carvalho 2007) and to do this in a ethical and responsible way (Weder & Rademacher, 2023).

So: What about the media corporations themselves? Do they need to be responsible?

CSR and media corporations

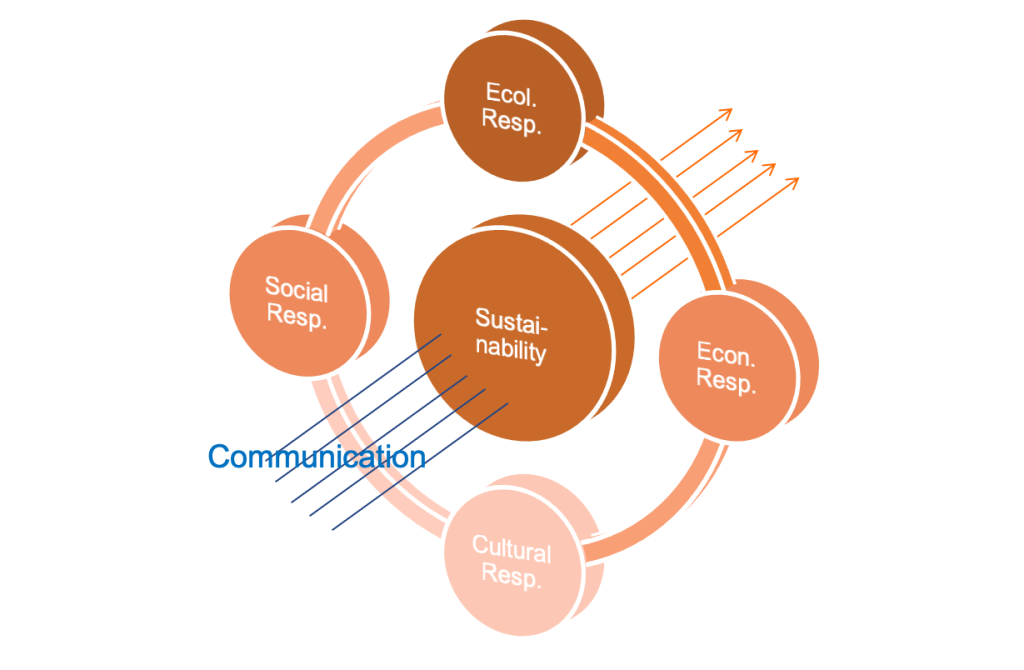

Then, CSR communication can be defined as the communication from and about organizations addressing actions within the organization that are (1) longer term measures (sustainable); and (2) voluntary (not legally bound). The actions reported have (3) a clear connection to the organization’s activities, but are not their objective (Weder & Jarolimek, 2017).

Image by Franzisca Weder

CSR communication is about giving information, responding to current and relevant issues (issue and crisis management) and involvement strategies (engagement, participation, community and stakeholder oriented) (further reading).

Therefore, not only as a side effect, the topic of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has also not left the media industry itself unaffected and becomes more and more relevant for media organizations (Weder et al. forthcoming). According to Trommershausen & Karmasin (2016) or Weder et al. (2021, 2023), the concept of responsibility is of importance to media business and news corporations, going beyond the discussion about press freedom, paywalls and fake news. Media and technology corporations like the BBC, google or facebook are also called upon to ensure public transparency by disclosing information on corporate social and environmental activities. The social responsibility of the media industry (also referred to as Media Social Responsibility; Altmeppen, 2011) shows the relevance of not only communicating about sustainability and environmental or social issues, but as well to communicate sustainable and responsible! (see BBC example).

Like the BBC points out, it’s not only about environmental and social responsibility or sustainable development as concept being represented in the program (or products or services). Much more, it is about communicating responsible and sustainable by the same time, here labelled as “Greener Broadcasting”.

So media corporations have a dual responsibility!

They are not only responsible because they

Media corporations are responsible for

- facilitating a sustainability related public discourses,

- offer conversational spaces for negotiation,

- play a key role in sustainability related meaning making processes and thus help to define sustainability as guiding (normative) principle,

- for how the sustainability is told and

- how they present and communicate the climate crisis and

- for what voices are heard – and who is not, thus for the ‘quality’ of the public discourse around sustainability and responsibility.

But they are also responsible for their own business, and how they respond to current issues as an organization.

If media in a broad understanding play a key role in translating, transmitting and disseminating an awareness of sustainability, they influence the mentioned societal discourses and introduce a certain understanding of the world and the human-nature relationship into social discourse. The media offer the space to problematize certain aspects of sustainability, they “make an issue out of certain topics” like food choices, mobility and transportation challenges or energy sourcing and supply. Furthermore, a certain morality is sneaking into public discourses, the media tell you what is good and bad, they not only problematize and bring in causalities, but also morally evaluate an issue (Entman, 1993).

In this context we need to talk about greenwashing and the role media play in this downside of CSR communication.

Good to know about …. Greenwashing

Social awareness and concern about climate change have dramatically increased since the turn of the millennium. Organisations are under increased environmental scrutiny now that organisational activity has been linked to an increase in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Rosenberg et al., 2019).

Environmental challenges and the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been shown to influence both consumer and stakeholder behaviour. As a result, investors, stakeholders, and customers prefer to deal with ethically ‘green’ businesses and projects rather than unethical ones (Pimonenko et al., 2020). Yet, due to the usage of greenwashing tactics by businesses, the rise in environmental information provided by businesses has also been accompanied by social doubts about its reliability (Mateo-Márquez et al., 2022).

Globally, people are becoming more aware of misleading or outright false environmental claims made by businesses, non-profits, and even governments when outlining their stances on environmental and climate change-related topics. These assertions can be used to boost an organization’s reputation, its relationships with clients and staff, or short-term financial success. All while avoiding the more significant effort, investment and/or reforms that are required to drastically reduce environmental harm. Greenwashing is still prevalent despite this rising awareness. According to a recent analysis of 500 international websites conducted by the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority and the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (as part of the International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Network), about 40% of ‘green’ organisational claims could be considered greenwashing (Nemes et al., 2022).

The phrase ‘greenwashing’ refers to a broad range of deceptive communications and behaviours that, whether on purpose or not, create falsely favourable opinions of an organization’s environmental performance. There are several levels of greenwashing, which can be carried out by businesses, governments, politicians, research organisations, international organisations, banks, NGOs, etc. It can vary from modest exaggeration to outright falsification. In summary, spreading incorrect or misleading information about an organisation’s environmental plans, aims, motives, and actions is “greenwashing” (Nemes et al., 2022).

The six forms of greenwashing are (see Greenwashing: 6 reasons why businesses do it for further information):

- Greenhushing – Understating or concealing sustainability credentials to avoid investor scrutiny.

- Greenrinsing – Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) aims are frequently modified before being attained.

- Greenlabelling – Selling a product as sustainable, but a closer look reveals that the claim is false.

- Greenshifting – Accusing the customer.

- Greenlighting – Highlighting a green initiative, no matter how little, to divert attention away from behaviours, organisations, or goods that are not sustainable.

- Greencrowding – depending on the principle of “safety in numbers” and the observation that the majority of people move slowly.

Additionally, greenwashing worsens consumers’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Furlow, 2010), and it appears to have a negative impact on consumers’ opinions of brands (Parguel et al., 2011), their levels of green trust (Chen & Chang, 2013), their perceptions of the environmental sustainability of corporations (Mason & Mason, 2012), their attitudes towards particular brands (Gatti et al., 2019), as well as their word-of-mouth (Chen, Lin, & Chang, 2014).

Consequences of Greenwashing

In 2015, researchers discovered that Volkswagen had installed specific software in some of their diesel vehicles. This software, referred to as a ‘defeat device’, allowed the vehicle to pass laboratory testing, while in general use emitting more than 40 times the emissions allowed in the U.S.A. (Jung & Sharon, 2019).

This can be classified as greenwashing and led to one of the largest corporate scandals in history. For Volkswagen, it reportedly resulted in losses of €7 billion in profits, as well as reputational and investments damage (the value of Volkswagen’s shares fell by 25%).

The fallout from this controversy was not just restricted to Volkswagen. It also led to a decrease in investor interest in the auto industry more broadly, and a decrease in consumer trust in the “Made in Germany” brand. Across the publicly listed automobile companies at the time, a 3–14% decline was seen in the value of their shares in 2015 (BMW by 88%, Honda by 13.73%, Ford by 12.42%, Mercedes by 6.51%, Fiat by 5.97%, General Motors by 4.32%, and Toyota by 3.24%) (Pimonenko et al., 2020).

Greenwashing also appears to have a negative impact on the company’s financial results. While greenwashing can occasionally be used to successfully divert attention away from poor CSR behaviour, it frequently appears to have a negative financial impact on businesses. Especially in the current environment, marked by intense scrutiny from civil society and rising stakeholder scepticism. Even when corporate communications are not deceptive and the accusation of greenwashing is unfounded, it can have a detrimental impact on the credibility and reputation of the company in question. Indeed, if the public thinks that the corporation is self-promotional, corporate CSR communications could backfire on the organisation. Because it is not profitable, businesses are now less driven to reduce their environmental impact. Hence, greenwashing eventually harms the environment as well as customers, businesses, and the public at large (Gatti et al., 2019).

Summary – most important take aways

Communication about CSR and sustainability is based on a constructivist understanding of communication; communication is happening on an intra- and interpersonal level, within organization and beyond and in a wider public sphere, conceptualized as ‘public discourse’. Communication are all processes of sense making, where an understanding and interpretation of the world is generated.

The media play a crucial role for the emergence and sustainability of the CSR related discourse. From a theoretical perspective, communication about CSR is mostly analyzed and explained with a focus on media and issues that are represented in traditional and new, digitalized forms of media. Over the years, the climate change story is now established in media reporting, as well as critical cases of greenwashing – both fit to the ‘bad stories are good stories’-logic of the media; however the sustainability story is less present in public discourses. Still, sustainability is a language token or ‘buzz word’ used in CSR communication (see chapter III.2.), the reporting on corporate misconducts, in transparency and ‘washing’ activities, but not further elaborated as a guiding principle of action on all levels, individual, organizational, social and ecological. Social transformation processes, sustainable development also don’t fit to the media logic of actual and on-time information and a relatively quick turnover from one highly mediated event to the next.

In the next chapter we will look at a different way to approach CSR and sustainability communication and identify communication processes that contribute to a socio-economic transformation process.

Further reading…

More academic literature on CSR & sustainability in the media:

CSR & the media:

Weder, F., Rademacher, L., Schmidpeter, R. (2023). CSR Communication in the Media. Media Management on Sustainability at a Global Level. Wiesbaden et al.., Springer.

Tench, R., Bowd, R., & Jones, B. (2007). Perceptions and perspectives: Corporate social responsibility and the media. Journal of Communication Management, 11(4), 348-370.

Schlichting, I. (2013). Strategic framing of climate change by industry actors: A meta-analysis. Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture, 7(4), 493-511.

Barkemeyer, R., Figge, F., Hoepner, A., Holt, D., Kraak, J. M., & Yu, P. S. (2017). Media coverage of climate change: An international comparison. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(6), 1029-1054.

Voci, D. (2022). Logos, ethos, pathos, sustainabilitos? About the role of media companies in reaching sustainable development. Sustainability, 14(5), 2591.

Fischer, D., Haucke, F., & Sundermann, A. (2017). What does the media mean by ‘sustainability’or ‘sustainable development’? An empirical analysis of sustainability terminology in German newspapers over two decades. Sustainable development, 25(6), 610-624.

Fischer, D., Lüdecke, G., Godemann, J., Michelsen, G., Newig, J., Rieckmann, M., & Schulz, D. (2016). Sustainability communication. Sustainability Science: An Introduction, 139-148.

Newig, J., Schulz, D., Fischer, D., Hetze, K., Laws, N., Lüdecke, G., & Rieckmann, M. (2013). Communication regarding sustainability: Conceptual perspectives and exploration of societal subsystems. Sustainability, 5(7), 2976-2990.

Kim, S., & Ferguson, M. T. (2014). Public expectations of CSR communication: What and how to communicate CSR. Public Relations Journal, 8(3), 1-22.

Greenwashing:

Seele, P., & Gatti, L. (2017). Greenwashing revisited: In search of a typology and accusation‐based definition incorporating legitimacy strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(2), 239-252.

Vollero, A. (2022). Greenwashing: Foundations and Emerging Research on Corporate Sustainability and Deceptive Communication.

Elving, W. J., Golob, U., Podnar, K., Ellerup-Nielsen, A., & Thomson, C. (2015). The bad, the ugly and the good: new challenges for CSR communication. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 20(2), 118-127.